Aetiology

Any chronic liver disease may cause cirrhosis. The most common causes of cirrhosis are alcohol-related liver disease, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and chronic viral hepatitis.[6][14]

Other less common but important causes of cirrhosis include cholestatic, autoimmune, and metabolic liver diseases.

When the aetiology of cirrhosis cannot be determined, it is considered 'cryptogenic'. The number of cases of cryptogenic cirrhosis is significantly declining, in part because it is becoming more evident that many cases are undiagnosed MASLD.

The various causes of cirrhosis are listed below.

Chronic viral hepatitis: hepatitis C and hepatitis B (with or without coexisting hepatitis D)

Alcohol-related liver disease

Metabolic disorders: MASLD, haemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, glycogen storage diseases, abetalipoproteinaemia

Immune-mediated liver disease: primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune cholangiopathy, immunoglobulin G4-related disease

Biliary obstruction: mechanical obstruction, biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis

Hepatic venous outflow obstruction: Budd-Chiari syndrome, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, right-sided heart failure

Drugs and toxins: amiodarone, methotrexate

Intestinal bypass: anastomosis of the jejunum to the ileum to shorten the length of the digestive tract in class III obesity (body mass index ≥40 kg/m²), or to bypass a diseased area or blockage

Indian childhood cirrhosis (environmental copper poisoning, now rare)

Cryptogenic cirrhosis.

Pathophysiology

Liver fibrosis has been described as a reversible, wound-healing response to either acute or chronic cellular injury which reflects a balance between liver repair and scar formation.[15] It occurs in most patients with any type of chronic liver injury and may ultimately evolve into cirrhosis with nodule formation.

The central event in hepatic fibrosis is the activation of hepatic stellate cells, which are the major source of extracellular matrix. This leads to an accumulation of collagen types I and III in the hepatic parenchyma and space of Disse.[3][15][16]

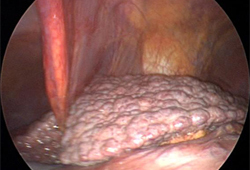

The result of collagen deposition in the space of Disse is termed 'capillarisation' of the sinusoids, a process in which the hepatic sinusoids lose their characteristic fenestration, thereby altering the exchange between hepatocytes and plasma. With activation, hepatic stellate cells become contractile, which may be a major determinant of increased portal resistance during liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.[17][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Laparoscopic view of a cirrhotic liverCourtesy of Dr Eugene Schiff and Dr Lennox Jeffers; used with permission [Citation ends].

This process is usually progressive and perturbs blood flow through the liver, thereby leading to increased pressure within the portal venous system, as well as shunting blood away from the liver.

In addition to architectural changes causing a fixed component of portal hypertension, dynamic changes to vascular tone resulting from an acute insult such as infection can influence portal pressure and result in acute decompensation.

These changes lead to portal hypertension, which underlies the development of ascites and gastro-oesophageal varices, and promotes the diversion of nutrient-carrying blood away from the liver, contributing to hepatic encephalopathy.[15][16]

An increase in vasoconstrictor signalling (such as endothelin-1) and decrease in the production of vasodilators (e.g., nitric oxide) may be seen in chronic liver injury, leading to restricted blood flow.[3] Vascular resistance is also increased by inflammation due to alcohol or steatosis. Further, chronic liver injury may also cause loss of hepatocytes and reduce the capacity of the liver to perform metabolic activities such as protein synthesis, detoxification, nutrient storage, and bilirubin clearance.[3] Patients may progress over time from a compensated state without clinical manifestations to a decompensated state with variceal haemorrhage, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy.[3] Portal hypertension (pressure gradient of ≥10 mmHg) may promote the development of varices. Gut-derived toxins such as ammonia and bacterial products that induce systemic inflammation result in hepatic encephalopathy.[3][18]

Cirrhosis can lead to malnutrition and importantly sarcopenia. This leads to frailty, which is increasingly recognised as a poor prognostic marker.[19][20] Sarcopenia results from anorexia; hypermetabolism; hyperammonaemia; malabsorption due to intraluminal bile acid deficiency and/or chronic pancreatitis; altered macronutrient metabolism; and micronutrient deficiencies.[21] Sarcopenia may affect about one third of patients with cirrhosis and is associated with approximately twofold increased mortality.[22][23] Risk factors for sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis include older age, male sex, lower body mass index, and presence of alcohol-related liver disease.[24]

Inadequate synthesis due to hepatic impairment combined with a catabolic state results in hypoalbuminaemia, which can worsen complications of liver cirrhosis such as ascites.

An immune system dysfunction can be seen in cirrhosis, disposing patients to bacterial, fungal, and viral infections.[25] Such patients are prone to develop multi-organ failure, which is associated with high mortality.[25] Bacterial infections are most common, with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis being the most frequently encountered bacterial infection.

Cirrhosis is a dynamic disease state with potential for reversibility if ongoing liver injury is halted. For example, a patient with decompensated cirrhosis related to alcohol may clinically recompensate with abstinence.[26] Similarly, serial biopsy studies have shown improvement of liver fibrosis following treatment of chronic viral hepatitis.[27]

There is likely a point after which liver cirrhosis is considered irreversible and the only treatment at that stage is liver transplantation. This may relate to the deposition of hepatic elastin, which is more resistant to remodelling.[28]

Classification

Compensated cirrhosis

In compensated cirrhosis, biochemical, radiological, or histological findings consistent with the pathological process of cirrhosis are present. Liver synthetic function is preserved and there is no evidence of complications related to portal hypertension, such as ascites, gastro-oesophageal varices and variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and/or jaundice.

Decompensated cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is regarded as decompensated when there is evidence of the development of complications of liver dysfunction with reduced hepatic synthetic function and portal hypertension including ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and/or jaundice. Decompensated cirrhosis is an umbrella term for a spectrum of disease. It usually occurs when the portal pressure gradient is ≥10 mmHg (known as ‘clinically significant portal hypertension’).[2]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Icterus or jaundiceCDC. Dr Thomas F. Sellers/Emory University; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer