Approach

The diagnosis of chancroid is classically based on history, clinical features on physical examination, and isolation of the causative organism with culture.[44]

However, it is important to note that clinical features are generally non-specific, culture of the organism can be difficult, and mixed infections are common. Co-infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV) and syphilis must therefore be excluded in all patients with suspected chancroid.[45][46][47][48][49][50]

History

A thorough history should be elicited in cases of suspected chancroid covering symptom, sexual, and travel history.

Symptom history

Patients will usually complain of a painful genital ulcer, inguinal tenderness, or, less commonly, purulent discharge. Inguinal tenderness is more common in men. Ulcers may be painless in women, especially if they occur on the vaginal walls or cervix.

Constitutional symptoms such as fever or rash are usually absent.[15] Women may present with more subtle symptoms such as dysuria, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, haematochezia, or pain on defecation.

Symptoms typically appear 3-7 days after unprotected intercourse with an infected partner.[31] The time from last sexual activity to symptom onset should be defined. Typically, there is no prodrome. Care is usually sought after the lesions ulcerate or become painful, or other symptoms develop.

Sexual history

Important features include the date of last sexual activity, history of unprotected sex with a person from an endemic region, condom use, contact with sex worker (self or partner), HIV status, history of other sexually transmitted infections, social history including drug and alcohol use, and the presence of any conditions that compromise the immune system.

Travel history

The local prevalence of chancroid or travel to an endemic area should be considered.

Physical examination

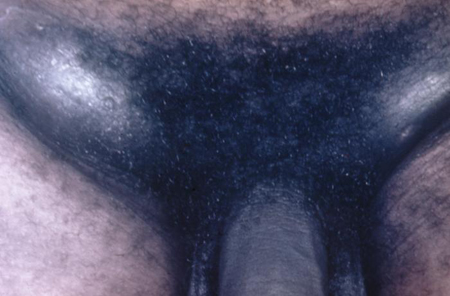

Ulcers usually measure 1-2 cm and have sharply demarcated borders with ragged, undermined edges and a friable base. The base may be covered with a greyish or yellow exudate. Induration is not present.

In men, the majority of ulcers are located on the prepuce or frenulum, or in the coronal sulcus. Less commonly, the glans, penile shaft, meatus, or anus is involved. Complications such as phimosis, urethral fistula, and secondary bacterial infection may also be present.[15][17][51] Urethral discharge may be seen but is uncommon.

In women, ulcers are usually on the fourchette, labia, vestibule, or clitoris. Larger peri-urethral ulcers may be present. The vaginal walls and cervix should be inspected, as these lesions are often painless and go unnoticed. Female patients are less likely to develop ulceration. Vaginal discharge may be present and complications such as rectovaginal or urethral fistula may be evident on examination.

Other types of ulcers include giant (>2 cm) or serpiginous ulcers, follicular ulcers, or papules with a raised border that resembles condyloma latum of secondary syphilis. Lesions may be <1 to 5 mm in diameter, resembling HSV lesions, and may form 'kissing lesions' on opposing surfaces. Vesicles are not seen. Women are more likely to have spontaneous resolution of papules, whereas men are more likely to progress to the pustular stage.[35][36]

Painful inguinal lymphadenitis is often present in about 50% of patients, mostly in men.[52] It is unilateral in approximately two-thirds of cases. In later stages, fluctuant lymphadenitis (buboes) may appear.

Extra-genital lesions are rare, usually resulting from autoinoculation and affecting the thighs, fingers, oropharynx, or breast (in women).[15][51][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Penile ulcers associated with chancroidAdapted from J. Miller, Public Health Image Library, CDC (1974) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chancroid pustule resembling syphilisAdapted from Public Health Image Library, CDC (1971) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chancroid pustule resembling syphilisAdapted from Public Health Image Library, CDC (1971) [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Buboes associated with Haemophilus ducreyi infectionAdapted from S. Lindsley, Public Health Image Library, CDC (1971) [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Buboes associated with Haemophilus ducreyi infectionAdapted from S. Lindsley, Public Health Image Library, CDC (1971) [Citation ends].

Testing for H ducreyi

The clinical diagnosis of chancroid is confirmed by swabbing genital lesions for culture to isolate H ducreyi colonies.[44] Sample collection should ideally be from the base of the lesion without surface genital skin as swabs from the ulcer base have a higher yield than those from the bubo.[53] Any urethral or vaginal discharge should also be swabbed.

Culture

The diagnostic standard for chancroid, in spite of relatively low sensitivity (53% to 92%) and the organism being fastidious and difficult to culture.[54] Specialised media are required to optimise growth. The recovery of H ducreyi is improved if culture is attempted in more than 1 type of media (MH-HB and/or GC-HgS). Vancomycin 3 micrograms/mL is added to inhibit growth of other bacteria.

Nucleic acid detection

In the US, there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for H ducreyi. However, some clinical laboratories have developed their own PCR test and have conducted verification studies in genital specimens.[55] The sensitivity (98%) and specificity (>90%) for detection of chancroid are better than with other methods.[56][57][58][59] Multiplex PCR tests have been developed that allow testing for several organisms simultaneously, including H ducreyi and HSV.[60][61] These technologies are available primarily at reference laboratories. Due to the difficulties with culture, PCR should be considered the test of choice where available.[53]

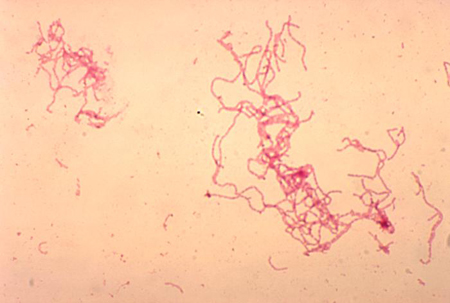

Gram staining

The classic appearance is of gram-negative coccobacilli or slender bacilli in a railroad or chaining pattern. The distinctive 'school of fish' arrangement has long parallel columns between cells or long chains of cells. Gram staining is not a reliable finding (sensitivity 5% to 63%; specificity 51% to 99%) because of the polymicrobial flora of most genital ulcers.[62][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Gram stain of Haemophilus ducreyiAdapted from G. Hammond, Public Health Image Library, CDC (1978) [Citation ends].

Serology

Serological tests to identify antibodies against H ducreyi are available. These do not distinguish current from past infection and are reserved for cases in which culture is non-diagnostic. Serology is useful for seroprevalence studies.

Additional laboratory investigations

Other tests for H ducreyi

Immunofluorescent detection: direct and indirect immunofluorescent testing of ulcer material has been done to detect H ducreyi. Monoclonal antibodies are designed to detect lipo-oligosaccharide or HbA antigens. However, these assays are not commercially available. Compared with culture, this method has a sensitivity as high as 93% for ulcer specimens, but the specificity is poor (63%).[2]

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: this can be done by agar dilution or E-test.[63] It is not used routinely due to difficulty in culturing H ducreyi, lack of standardisation, and lack of interpretive guidelines. Studies have shown in vitro resistance to tetracyclines, sulfonamides, penicillins, and amoxicillin/clavulanate. However, the majority of isolates remain susceptible to rifamycins, quinolones, macrolides, and streptomycin.[17][26][64][65] Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is usually reserved for cases in which response to antibiotic therapy is poor.

Investigations to rule out an alternative or comorbid diagnosis

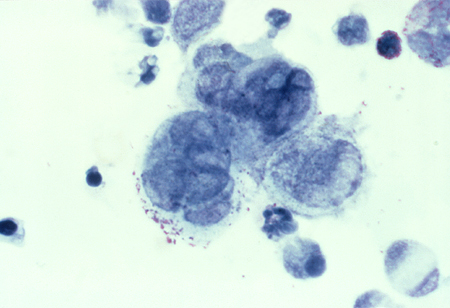

Detection of HSV: PCR or viral culture should be carried out to exclude HSV infection. A Tzanck smear of the biopsy can be used to diagnose HSV in ambiguous cases. It shows the characteristic appearance of multi-nucleated giant cells and epithelial cells containing eosinophilic intra-nuclear inclusion bodies. This test is only used if herpes is strongly suspected, and PCR testing and viral cultures are inconclusive.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tzanck test specimen showing multi-nucleated giant cells, indicating the presence of herpes virusAdapted from J. Miller, Public Health Image Library, CDC (1975) [Citation ends].

See Herpes simplex virus infection.

See Herpes simplex virus infection.Detection of Treponema pallidum (syphilis): The most common approach is to use a treponemal test as the initial serological test, followed by a non-treponemal test to confirm diagnosis and provide evidence of active disease or re-infection (i.e., a ‘reverse sequence screening algorithm’).[66] However, use of a traditional screening algorithm (initial investigation with a non-treponemal test followed by a treponemal test) is also acceptable. Dark-field microscopy of a lesion swab can provide a definitive diagnosis of syphilis, but it is not usually available outside of consultant settings. See Syphilis infection.

HIV testing: chancroid is an important co-factor in the transmission of HIV; therefore, HIV status should also be assessed as part of the diagnostic work-up.[27] Local guidance for HIV testing varies. See HIV infection.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer