Approach

The response to any given therapy is dependent on the underlying mechanism of the arrhythmia. Focal atrial tachycardias due to triggered activity may be terminated by adenosine or overdrive pacing, but the response to beta blockers or calcium channel blockers may be variable. Arrhythmias caused by enhanced automaticity often convert spontaneously on withdrawal of the offending agent. They can be transiently suppressed by adenosine or by overdrive pacing and may be terminated by beta blockers or calcium channel blockers. Persistent arrhythmias of this type are often resistant to pace termination, electrical cardioversion, and pharmacological therapy, and they ultimately require catheter ablation. A micro-re-entrant atrial tachycardia response to adenosine, beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers may be variable. Re-entrant arrhythmias may require direct current (DC) cardioversion and, possibly, use of antiarrhythmic drugs. Electrophysiological study involving ablation can be curative and may be offered as first-line therapy to select patients.[1]

The mechanisms of focal atrial tachycardia (focal AT) are difficult to distinguish clinically. There is no clear hierarchy of therapies. The presence of an underlying cause, comorbid conditions, haemodynamic status, and patient preference can be used to guide initial therapy.[15]

Differentiating the type of arrhythmia

Adenosine causes AV node blockade with slowing of the ventricular response rate or cessation of the atrial tachycardia and can be helpful in differentiating focal AT from other supraventricular tachycardias.[13] Effects are usually transient. If the focal AT terminates with adenosine then the information provided may be misleading or limited. For example, when attempting to differentiate atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia/atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia from focal AT, adenosine may cause transient AV block with persistent atrial tachycardia, supporting the diagnosis of focal AT. The response to adenosine may also assist in identifying the atrial tachycardia mechanism. Focal AT due to triggered activity may terminate with adenosine, in contrast with re-entrant atrial tachycardias, which usually do not.[1][14][16]

The telemetry strip during administration should be carefully inspected for placement of P waves at the time the rhythm breaks. A very short RP interval with a final P wave suggests a re-entrant supraventricular tachycardia.

Transient slowing of the ventricular response rate with sustained atrial activity indicates flutter or focal AT. Flutter will have the characteristic saw-tooth pattern of an atrial macro-re-entrant circuit. Focal AT will show discrete P waves with an isoelectric baseline.

Lack of response to adenosine suggests either sinus tachycardia or focal AT, and strongly suggests that the rhythm is not re-entrant supraventricular tachycardia or atrial flutter.

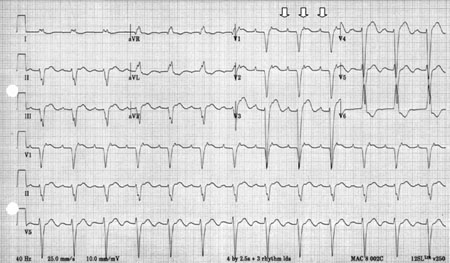

Some forms of atrial tachycardia will break in response to adenosine.[17][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Response to adenosine 6 mg intravenouslyFrom the collection of Sarah Stahmer, MD [Citation ends]. Electrophysiological study (EPS) can identify the site of the tachycardia and underlying mechanism. EPS involving ablation can be curative and may be offered as first-line therapy to select patients.[1]

Electrophysiological study (EPS) can identify the site of the tachycardia and underlying mechanism. EPS involving ablation can be curative and may be offered as first-line therapy to select patients.[1]

General principles for treating patients with focal AT

Patients are usually symptomatic due to the increased heart rate, which is uncomfortable but also may exacerbate underlying conditions, such as coronary artery disease or valvular heart disease. Treatment efforts should focus on ensuring haemodynamic stability, and treating complications of the rhythm such as congestive heart failure, which usually require slowing the heart rate. This may be difficult in some cases, and interventions should be chosen with careful consideration of the clinical context.

The clinical context is often the primary clue to the underlying mechanism. For example, focal AT in the context of acute alcohol intoxication is probably because of enhanced automaticity. These often convert spontaneously once the offending agent (alcohol, cocaine, or amphetamines) is withdrawn. Those that do not resolve spontaneously are often resistant to pace termination (which produces, at best, only a transient suppression of the arrhythmia), electrical cardioversion, and pharmacological therapy. Catheter ablation is often the only effective treatment.

If there is a history of known cardiac defect or prior cardiac surgery, the focal AT may be due to re-entry. Re-entry arrhythmias are amenable to pace termination, cardioversion, ablation, and pharmacological intervention. Of interest is the fact that repair of cardiac defects may reduce the incidence of focal AT.[18]

Triggered arrhythmias are difficult to distinguish clinically. They are known to behave in a fashion somewhere in between that of automatic and re-entrant arrhythmias and are therefore more amenable to pharmacological intervention.

Digoxin toxicity

Digoxin toxicity should be suspected if there is a history of congestive heart failure, the patient is taking digoxin, and the rhythm is atrial tachycardia with evidence of atrioventricular blockade.

Initial work-up should focus on determining whether the patient is haemodynamically compromised from the rhythm itself and, if so, considering digoxin immune antibody fragments (Fab) therapy if the patient is found to be digoxin toxic. The treatment is supportive care while repleting potassium and/or withholding digoxin.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Focal atrial tachycardia in an 88-year-old woman with 2:1 AV nodal block in the setting of digoxin therapy and potassium 2.8 mmol/L (2.8 mEq/L)From the collection of Sarah Stahmer, MD [Citation ends].

Approach to initial treatment in patients with focal AT; digoxin excess not suspected

Intravenous beta-blockers, or the calcium-channel blockers diltiazem and verapamil, are recommended as first-line therapy to treat focal AT. For those patients who do not respond to these initial interventions, amiodarone or ibutilide may be effective. In the acute setting, the benefit of amiodarone may be due to its beta-blocking effects, but better tolerated than beta-blockers in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Ibutilide has been reported to be effective in some cases of focal AT, but its mechanism of action is not clear.[1][16] EPS involving ablation can be curative and may be offered as first-line therapy to select patients who prefer to avoid long-term pharmacological therapy e.g., younger patients or those with certain occupations, such as pilots.[1] Catecholamine excess is largely suspected by a history of medication use, cocaine, amphetamines, or alcohol withdrawal with clinical features of catecholamine excess on examination (agitation, diaphoresis, hypertension).

Focal AT can be caused by sudden surges in circulating catecholamines through use of amphetamines, cocaine, or products containing catecholamines. Patients are rarely haemodynamically compromised, and treatment should be supportive. Those who do not respond to supportive measures, do not have a history of cocaine use, and are haemodynamically unstable may be treated with beta-blockers. Those who are still refractory may be treated with direct current (DC) cardioversion.

Patients who are haemodyamically compromised or have drug-resistant rhythms are candidates for synchronised cardioversion.[16] The response to cardioversion is dependent in part on the underlying mechanism of the tachycardia. Micro-re-entrant tachycardias are likely to readily convert to sinus rhythm, triggered focal AT will have a variable response, and cardioversion is not likely to be effective in focal AT with an automatic mechanism.

Approach to sustained, refractory or recurrent focal AT

Management of focal AT beyond the initial stabilisation period and for those refractory to initial interventions may benefit from additional pharmacological therapy, which should be done in consultation with a cardiologist. Class Ic antiarrhythmics are first choice and class III antiarrhythmics second choice.

Many patients with sustained and/or recurrent atrial tachycardias are referred for catheter ablative therapy. The success of this treatment depends on the site of origin and underlying mechanism.[1]

Children

Paediatric atrial tachycardias are uncommon. Atrial tachycardia in children is often incessant and refractory to typical treatments used for atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia; tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy is commonly observed. The cause is usually idiopathic but identified risk factors include viral infections, atrial tumours, and surgery for congenital heart disease.

The treatment of paediatric patients with atrial tachycardia includes medications to suppress the arrhythmia and/or control the ventricular response and catheter ablation. Beta-blockers, digoxin, and antiarrhythmics are often effective as first-line pharmacological interventions to achieve rate control. Many children will have spontaneous resolution of the arrhythmia. Patients with incessant tachycardias will usually require catheter ablation, which is associated with a high degree of success, a low complication rate, and a low recurrence rate.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer