Oral leukoplakia as defined by the World Health Organization is a predominantly white lesion of the oral mucosa that cannot be characterized as any other definable lesion.[1]Kramer IR, Lucas RB, Pindborg JJ, et al. Definition of leukoplakia and related lesions: an aid to studies on oral precancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978 Oct;46(4):518-39.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/280847?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Axell T, Holmstrup P, Kramer IRH, et al. International seminar on oral leukoplakia and associated lesions related to tobacco habits. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1984 Jun;12(3):145-54.[3]Axell T, Pindborg JJ, Smith CJ, et al. Oral white lesions with special reference to precancerous and tobacco-related lesions: conclusions of an international symposium held in Uppsala, Sweden, May 18-21 1994. International Collaborative Group on Oral White Lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996 Feb;25(2):49-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8667255?tool=bestpractice.com

Thus, diagnosis is one of exclusion of all other possible diagnoses of known white lesions. For many lesions an alternative diagnosis may be suggested following a thorough history and clinical examination, with confirmation by biopsy if clinical doubt exists.[59]Sankaranarayanan R, Fernandez Garrote L, Lence Anta J, et al. Visual inspection in oral cancer screening in Cuba: a case-control study. Oral Oncol. 2002 Feb;38(2):131-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11854059?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Shugars DC, Patton LL. Detecting, diagnosing, and preventing oral cancer. Nurse Pract 1997 Jun;22(6):105;109-10;113-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9211456?tool=bestpractice.com

A thorough investigation and accurate diagnosis is essential because, while many leukoplakias may be benign, some have a significant potential for malignant transformation to oral squamous cell carcinoma.[61]Waldron CA, Shafer WG. Leukoplakia revisited. A clinicopathologic study 3256 oral leukoplakias. Cancer. 1975 Oct;36(4):1386-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1175136?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Wright JM. Oral precancerous lesions and conditions. Semin Dermatol. 1994 Jun;13(2):125-31.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8060824?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Jaber MA, Porter SR, Gilthorpe MS, et al. Risk factors for oral epithelial dysplasia - the role of smoking and alcohol. Oral Oncol. 1999 Mar;35(2):151-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10435149?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Petti S, Scully C. Association between different alcoholic beverages and leukoplakia among non- to moderate-drinking adults: a matched case-control study. Eur J Cancer. 2006 Mar;42(4):521-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16427777?tool=bestpractice.com

As such, the clinician should be aware of the importance of leukoplakia and its range of behaviors, as early diagnosis of potentially malignant lesions can also reduce morbidity and mortality.[64]Sankaranarayanan R. Screening for cervical and oral cancers in India is feasible and effective. Natl Med J India. 2005 Nov-Dec;18(6):281-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16483024?tool=bestpractice.com

Histologic examination is recommended to assess the presence and degree of any epithelial dysplasia, which has conventionally been the method used to predict malignant potential.[65]Mashberg A, Samit A. Early diagnosis of asymptomatic oral and oropharyngeal squamous cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 1995 Nov-Dec;45(6):328-51.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/canjclin.45.6.328/epdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7583906?tool=bestpractice.com

In parts of the world, dentists may not be trained to perform a biopsy; therefore, referral to a specialist for such a procedure is advised.

Leukoplakias with malignant potential

Potentially malignant oral mucosal lesions (oral precancers) mainly include some leukoplakias and erythroplakia (also known as erythroleukoplakia). Erythroplakia, though much less common than leukoplakias, has higher malignant potential. Erythroplakia presents as a velvety red plaque, and at least 85% of cases show frank malignancy or severe epithelial dysplasia.[66]Quah SR, Cockerham WC, eds. International encyclopedia of public health. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2017. Leukoplakia, particularly where admixed with red lesions (speckled leukoplakia), is potentially malignant. By utilizing a binary microscopic classification system, where lesions were classified as low-risk dysplasia or high-risk dysplasia, the latter was a significant indicator for evaluating malignant transformation.[67]Liu W, Wang YF, Zhou HW, et al. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia: a retrospective cohort study of 218 Chinese patients. BMC Cancer. 2010 Dec 16;10:685.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3009685/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21159209?tool=bestpractice.com

Lesions including proliferative verrucous leukoplakia, sublingual leukoplakia (sublingual keratosis), and candidal leukoplakia also have a higher malignant potential, with proliferative verrucous leukoplakia having a more significant risk of malignant transformation compared with the other leukoplakia subsets. One large case-cohort study of US adults ages 65 years and older found that patients with oral cancer and prior leukoplakia had a lower risk of death related to this cancer than those who developed oral squamous carcinoma without a leukoplakia precursor. The study concluded that leukoplakia identification and analysis can lead to earlier detection of cancer and improve levels of survival.[68]Yanik EL, Katki HA, Silverberg MJ, et al. Leukoplakia, oral cavity cancer risk, and cancer survival in the US elderly. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2015 Sept;8(9):857-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4560597?tool=bestpractice.com

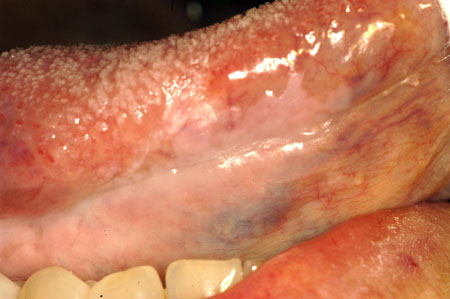

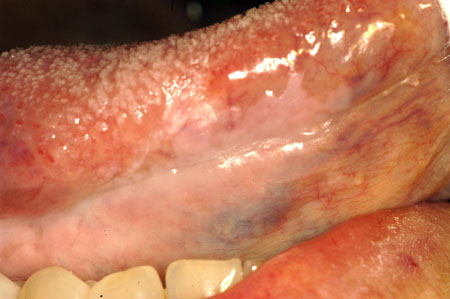

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ErythroplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Speckled leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Speckled leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative verrucous leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative verrucous leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sublingual leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sublingual leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Candidal leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Candidal leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

Clinical examination

A thorough examination of the oral cavity and the regional lymph nodes is essential. Many potentially malignant oral lesions (including leukoplakia) and cancers can be detected visually but can easily be overlooked, especially if the examination is not thorough.[59]Sankaranarayanan R, Fernandez Garrote L, Lence Anta J, et al. Visual inspection in oral cancer screening in Cuba: a case-control study. Oral Oncol. 2002 Feb;38(2):131-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11854059?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Shugars DC, Patton LL. Detecting, diagnosing, and preventing oral cancer. Nurse Pract 1997 Jun;22(6):105;109-10;113-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9211456?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Massano J, Regateiro FS, Januario G, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: review of prognostic and predictive factors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006 Jul;102(1):67-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16831675?tool=bestpractice.com

The possibility of widespread mucosal alterations ("field change") or a second neoplasm mandates that the whole oral mucosa be examined.[70]Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953 Sept;6(5):963-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13094644?tool=bestpractice.com

Molecular changes indicative of malignant potential may not produce clinically evident lesions and may extend well beyond the clinically identifiable lesion, which in part explains the increased risk for second primary tumors in patients with oral precancer and cancer.[71]Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH, Leemans CR. Head and neck cancer: molecular carcinogenesis. Ann Oncol. 2005 June 1;16(suppl 2):ii249-50.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)57637-2/pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15958466?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Braakhuis BJ, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. Expanding fields of genetically altered cells in head and neck squamous carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005 Apr;15(2):113-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15652456?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Tabor MP, Brakenhoff RH, Ruijter-Schippers HJ, et al. Genetically altered fields as origin of locally recurrent head and neck cancer: a retrospective study. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 June 1;10(11):3607-13.

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/10/11/3607.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15173066?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter's concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003 Apr 15;63(8):1727-30.

http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/63/8/1727

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12702551?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Lippman SM, Hong WK. Second malignant tumors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: the overshadowing threat for patients with early-stage disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989 Sept;17(3):691-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2674081?tool=bestpractice.com

Some common conditions that may cause diagnostic confusion include Fordyce granules and geographic tongue. Collections of debris (materia alba) or fungi (candidiasis) may also look white, but these can usually easily be wiped off with a gauze pad. Other lesions appear white usually because they are composed of thickened keratin. Oral hairy leukoplakia, a lesion of viral etiology, is seen mainly in immunosuppressed people (e.g., HIV infection) and has no known malignant potential.

White lesions are usually painless but can be focal, multifocal, striated, or diffuse, and these features may guide the diagnosis. For example:

Focal lesions are often caused by cheek biting, at the occlusal line

Multifocal lesions are common in thrush (pseudomembranous candidiasis) and lichen planus; striated lesions are typical of lichen planus

Diffuse white areas are seen in the buccal mucosa in leukoedema and in the palate in stomatitis nicotina.

Other causes of white oral lesions must be considered. Following exclusion of these causes, a diagnosis of leukoplakia can be made.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Homogeneous leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral hairy leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral hairy leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lip-cheek bitingCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lip-cheek bitingCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

Causes of white oral lesions

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Causes of white oral lesionsCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre team [Citation ends].

Tests to exclude other diagnoses

Although, in many cases, such causes can be diagnosed following a careful history and physical examination, others may be confirmed only following a representative biopsy of the lesion. Additional laboratory investigation may also aid in excluding alternative diagnoses. These may include Treponema pallidum serology, and autoantibody testing where mucosal lupus erythematosus is considered possible.

First-line testing

The difficulty is in determining the malignant potential of the leukoplakia, which requires an appreciation of specific clinical forms and attendant likelihood for transformation. However, clinical diagnosis alone is insufficient in establishing and excluding malignant and premalignant disease; even experienced, highly trained professionals cannot identify all precancers and early stage oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) by visual inspection alone.[76]Silverman S Jr. Early diagnosis of oral cancer. Cancer. 1988 Oct 15;62(suppl 8):1796-99.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3167796?tool=bestpractice.com

Furthermore, the recognized classic features of OSCC, such as ulceration, induration, elevation, bleeding, and cervical lymphadenopathy, are features of advanced disease, not early stage disease.[77]Mashberg A, Feldman LJ. Clinical criteria for identifying early oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: erythroplasia revisited. Am J Surg. 1988 Oct;156(4):273-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3177749?tool=bestpractice.com

Unfortunately, clinical data suggest that there is often a substantial delay in obtaining a biopsy specimen, even when oral lesions display characteristics of frank cancers.[78]Scully C, Malamos D, Levers BG, et al. Sources and patterns of referrals of oral cancer: role of general practitioners. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986 Sept 6;293(6547):599-601.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1341389

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3092946?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]Dimitroulis G, Reade P, Wiesenfeld D. Referral patterns of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma, Australia. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1992 Jul;28B(1):23-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1422466?tool=bestpractice.com

Biopsy

An incisional biopsy is invariably indicated for most leukoplakias and should be sufficiently large and representative. An excisional biopsy should be avoided, because this is unlikely to have excised an adequately wide margin of tissue if the lesion is proven malignant, and may limit for the surgeon the clinical evidence of the site and character of the lesion.

False-negative results are occasionally possible from incisional biopsy and, even where dysplasia has been excluded in a leukoplakia by incisional biopsy, studies have shown that the lesions if wholly excised may prove to contain OSCC in up to 10% of patients.[80]Chiesa F, Sala L, Costa L, et al. Excision of oral leukoplakias by CO2 laser on an outpatient basis: a useful procedure for prevention and early detection of oral carcinomas. Tumori. 1986 Jun 30;72(3):307-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3739009?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Holmstrup P, Vedtofte P, Reibel J, et al. Oral premalignant lesions: is a biopsy reliable? J Oral Pathol Med. 2007 May;36(5):262-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17448135?tool=bestpractice.com

This is explained in part by data showing that early malignant changes can be scattered through and beyond a potentially malignant clinical lesion.[72]Braakhuis BJ, Leemans CR, Brakenhoff RH. Expanding fields of genetically altered cells in head and neck squamous carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005 Apr;15(2):113-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15652456?tool=bestpractice.com

[82]Califano J, Westra WH, Meininger G, et al. Genetic progression and clonal relationship of recurrent premalignant head and neck lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2000 Feb;6(2):347-52.

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/6/2/347

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10690509?tool=bestpractice.com

Because red rather than white areas are most likely to show any dysplasia, a biopsy should include the former.

Pathology

Histopathologic analysis by an experienced pathologist is a crucial aspect of management, as interobserver and intraobserver variability between pathologists is significant.[83]Abbey LM, Kaugars GE, Gunsolley JC, et al. Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability in the diagnosis of oral epithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995 Aug;80(2):188-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7552884?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Karabulut A, Reibel J, Therkildsen MH, et al. Observer variability in the histologic assessment of oral premalignant lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995 May;24(5):198-200.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7616457?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Fischer DJ, Epstein JB, Morton TH, et al. Interobserver reliability in the histopathologic diagnosis of oral premalignant and malignant lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004 Feb;33(2):65-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14720191?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Fischer DJ, Epstein JB, Morton TH Jr, et al. Reliability of histologic diagnosis of clinically normal intraoral tissue adjacent to clinically suspicious lesions in former upper aerodigestive tract cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2005 May;41(5):489-96.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15878753?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Woolgar JA. Histopathological prognosticators in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2006 Mar;42(3):229-39.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16150633?tool=bestpractice.com

If, following an initial biopsy, clinical doubt remains as to whether a representative sample has been taken (e.g., if the pathology report denies malignancy and yet clinically this is suspected), a repeat biopsy is indicated.

On routine histologic analysis leukoplakias demonstrate a wide range of histologic features ranging from benign to dysplastic changes of varying degrees. Benign histologic features include ortho/parakeratosis with no sign of keratin in areas deep to the surface (dyskeratosis, a feature of dysplasia). Additionally, a thickening or increase in the overall volume of the spinous or prickle cell layer (acanthosis) is commonly observed. Notably, in the majority of leukoplakias (over 60%) only hyperkeratosis with or without acanthosis will be found on microscopic analysis.[88]Lathanasupkul P, Poomsawat S, Punyasingh J. A clinicopathologic study of oral leukoplakia and erythroplakia in a Thai population. Quintessence Int. 2007 Sept;38(8):e448-55.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17823667?tool=bestpractice.com

Definitive cellular atypia within the basal and more superficial layers of the epithelium are often absent. However, one study in a Thai population found 10.6% of leukoplakias were dysplastic in nature, while 4.9% were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma.[88]Lathanasupkul P, Poomsawat S, Punyasingh J. A clinicopathologic study of oral leukoplakia and erythroplakia in a Thai population. Quintessence Int. 2007 Sept;38(8):e448-55.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17823667?tool=bestpractice.com

Where present the assessment of epithelial dysplasia should be graded (e.g., mild, moderate, or severe).[89]Odell E, Kujan O, Warnakulasuriya S, et al. Oral epithelial dysplasia: recognition, grading and clinical significance. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1947-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34418233?tool=bestpractice.com

Intraepithelial neoplasia, a concept created for the uterine cervix and extended to other mucosae, has been adapted to the oral mucosa (oral intraepithelial neoplasia) and used by some as a diagnostic term.[90]Kuffer R, Lombardi T. Premalignant lesions of the oral mucosa: a discussion about the place of oral intraepithelial neoplasia (OIN). Oral Oncol. 2002 Feb;38(2):125-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11854058?tool=bestpractice.com

[89]Odell E, Kujan O, Warnakulasuriya S, et al. Oral epithelial dysplasia: recognition, grading and clinical significance. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1947-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34418233?tool=bestpractice.com

Microscopic epithelial changes structured under architectural changes or cellular atypical features and associated with premalignancy or epithelial dysplasia include the presence of the following:[5]Warnakulasuriya S, Kujan O, Aguirre-Urizar JM, et al. Oral potentially malignant disorders: a consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1862-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33128420?tool=bestpractice.com

Architectural features

Increased number of mitotic figures

Abnormally superficial mitoses

Premature keratinization in single cells (dyskeratosis)

Keratin pearls within rete ridges

Loss of epithelial cell cohesion.

Cytologic features

Abnormal variation in nuclear size

Abnormal variation in nuclear shape

Abnormal variation in cell size

Abnormal variation in cell shape

Increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio

Atypical mitotic figures

Increased number and size of nucleoli

Hyperchromasia.

A binary grading system classifying dysplasias as low and high risk has also been proposed.[89]Odell E, Kujan O, Warnakulasuriya S, et al. Oral epithelial dysplasia: recognition, grading and clinical significance. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1947-76.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34418233?tool=bestpractice.com

Adjunctive diagnostic techniques

There are a number of adjunctive diagnostic aids to assist in the clinical assessment of oral mucosal pathology. However, evidence of efficacy is lacking.[91]Rethman M, Carpenter W, Cohen EE, et al. Evidence-based clinical recommendations regarding screening for oral squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010 May;14(5):509-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20436098?tool=bestpractice.com

[92]Fedele S. Diagnostic aids in the screening of oral cancer. Head Neck Oncol. 2009 Jan 30;1:5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2654034/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19284694?tool=bestpractice.com

Based on an evidence-based clinical practice guideline issued by the American Dental Association (ADA), these include:[93]Lingen MW, Abt E, Agrawal N, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity: a report of the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017 Oct;148(10):712-27;e10.

https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(17)30701-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28958308?tool=bestpractice.com

A description of each of these triaging tools is given below.

Brush biopsy

An oral brush biopsy may be used to exclude dysplasia among common, harmless-appearing oral lesions that do not appear suggestive enough to warrant a scalpel biopsy. This test uses a small nylon brush to gather cell samples of a suspicious area, which are then sent for computer analysis. Specimen collection is simple, causes little or no pain or bleeding, and requires no anesthetic; however, accurate sampling of the abnormality is necessary. A printout of any abnormal cells from the computer display and a written pathologist's report are returned to the clinician with a recommendation for a conventional incisional biopsy if significant abnormalities are detected.

This test has been reported to have a sensitivity greater than 92% to 96% and specificity of more than 90% to 94% in detecting epithelial dysplasia and OSCC, with a positive predictive value of 38% to 44%.[94]Sciubba JJ. Improving detection of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions: computer-assisted analysis of the oral brush biopsy. U.S. Collaborative OralCDx Study Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999 Oct;130(10):1445-57.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10570588?tool=bestpractice.com

[95]Scheifele C, Schmidt-Westhausen A, Dietrich T, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the OralCDx technique: evaluation of 103 cases. Oral Oncol. 2004 Sept;40(8):824-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15288838?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Svirsky JA, Burns JC, Carpenter WM, et al. Comparison of computer-assisted brush biopsy results with follow up scalpel biopsy and histology. Gen Dent. 2002 Nov-Dec;50(6):500-3.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12572180?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Kosicki DM, Riva C, Pajarola GF, et al. Oral CDx brush biopsy - a tool for early diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma [in German]. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2007;117(3):222-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17425240?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Poate TW, Buchanan JA, Hodgson TA, et al. An audit of the efficacy of the oral brush biopsy technique in a specialist Oral Medicine unit. Oral Oncol. 2004 Sept;40(8):829-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15288839?tool=bestpractice.com

Brush biopsy has been used to detect OSCC missed in scalpel biopsy.[99]Remmerbach TW, Weidenbach H, Hemprich A, et al. Earliest detection of oral cancer using non-invasive brush biopsy including DNA-image-cytometry: report on four cases. Anal Cell Pathol. 2003;25(4):159-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14501082?tool=bestpractice.com

However, case reports of OSCC in patients where brush biopsy results were negative have been reported.[100]Potter TJ, Summerlin DJ, Campbell JH. Oral malignancies associated with negative transepithelial brush biopsy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003 Jun;61(6):674-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12796875?tool=bestpractice.com

Outcomes of brush biopsy may be improved with the use of molecular techniques (e.g., p53 mutations, DNA cytometry, and AgNOR [nucleolar organizer region protein counts visualized by the argyrophil technique] counts).[101]Scheifele C, Schlechte H, Bethke G, et al. Detection of TP53-mutations in brush biopsies from oral leukoplakias [in German]. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2002 Nov;6(6):410-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12447653?tool=bestpractice.com

[102]Remmerbach TW, Mathes SN, Weidenbach H, et al. Noninvasive brush biopsy as an innovative tool for early detection of oral carcinomas [in German]. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2004 Jul;8(4):229-36.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15293118?tool=bestpractice.com

[103]Maraki D, Becker J, Boecking A. Cytologic and DNA-cytometric very early diagnosis of oral cancer. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004 Aug;33(7):398-404.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15250831?tool=bestpractice.com

[104]Remmerbach TW, Weidenbach H, Muller C, et al. Diagnostic value of nucleolar organizer regions (AgNORs) in brush biopsies of suspicious lesions of the oral cavity. Anal Cell Pathol. 2003;25(5):139-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12775918?tool=bestpractice.com

Vital staining with toluidine blue

Toluidine blue (TB) is a metachromatic stain that is easily available, economic, and has a high affinity for DNA and RNA. It rapidly stains abnormal tissues, but not normal mucosa. Several studies have demonstrated the ability of TB to detect oral premalignant lesions, including oral leukoplakia and oral cancers, with a high sensitivity. However, the stain is also taken up by other ulcerative conditions and, therefore, the specificity of the technique is low.[105]Jayasinghe RD, Hettiarachchi PVKS, Amugoda D, et al. Validity of toluidine blue test as a diagnostic tool for high risk oral potentially malignant disorders - a multicentre study in Sri Lanka. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020 Oct-Dec;10(4):547-51.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7475265

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32923360?tool=bestpractice.com

Optical systems

Interest has been increasing in the potential use of optical spectroscopy systems to provide tissue diagnosis in a real-time and noninvasive fashion.[106]Swinson B, Jerjes W, El-Maaytah M, et al. Optical techniques in diagnosis of head and neck malignancy. Oral Oncol. 2006 Mar;42(3):221-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16140566?tool=bestpractice.com

[107]Suhr MA, Hopper C, Jones L, et al. Optical biopsy systems for the diagnosis and monitoring of superficial cancer and precancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000 Dec;29(6):453-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11202330?tool=bestpractice.com

[108]Sharwani A, Jerjes W, Salih V, et al. Assessment of oral premalignancy using elastic scattering spectroscopy. Oral Oncol. 2006 Apr;42(4):343-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16321565?tool=bestpractice.com

Autofluorescence-based imaging systems are simple, manual hand-held devices based on the direct visualization of tissue fluorescence. Abnormal tissue typically appears as an irregular, dark area that stands out against the otherwise normal, green fluorescence pattern of surrounding healthy tissue.[109]Awan KH, Morgan PR, Warnakulasuriya S. Utility of chemiluminescence (ViziLite™) in the detection of oral potentially malignant disorders and benign keratoses. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011 Aug;40(7):541-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21615500?tool=bestpractice.com

[110]Awan KH, Morgan PR, Warnakulasuriya S. Evaluation of an autofluorescence based imaging system (VELscope™) in the detection of oral potentially malignant disorders and benign keratoses. Oral Oncol. 2011 Apr;47(4):274-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21396880?tool=bestpractice.com

Another technique involves an acetic acid oral rinse, after which the mucosa is examined using a blue-white light source. The light source is generated by a chemical reaction, hence the term chemiluminescence. The basis of the test is that oral leukoplakia has a differential tissue reflectance, and the patch may appear “whiter” with enhanced visibility and improved sharpness of the lesion during the examination. However, the specificity of the test is low.[109]Awan KH, Morgan PR, Warnakulasuriya S. Utility of chemiluminescence (ViziLite™) in the detection of oral potentially malignant disorders and benign keratoses. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011 Aug;40(7):541-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21615500?tool=bestpractice.com

Such optical adjuncts may assist in identification of mucosal lesions and in selection of biopsy sites.[111]Mendonca P, Sunny SP, Mohan U, et al. Non-invasive imaging of oral potentially malignant and malignant lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2022 Jul;130:105877.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35617750?tool=bestpractice.com

It may also assist in identification of cellular and molecular abnormalities not visible to the naked eye on routine examination, and provide additional information on tissue adjacent to the mucosal lesion.[112]Westra WH, Sidransky D. Fluorescence visualization in oral neoplasia: shedding light on an old problem. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Nov 15;12(22):6594-7.

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/12/22/6594

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17121876?tool=bestpractice.com

[113]Rosin MP, Cheng X, Poh C, et al. Use of allelic loss to predict malignant risk for low-grade oral epithelial dysplasia. Clin Cancer Res. 2000 Feb;6(2):357-62.

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/6/2/357

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10690511?tool=bestpractice.com

Data are conflicting as to the clinical benefits; studies have shown detection rates (for dysplastic lesions) similar to those of conventional clinical diagnosis and biopsy site selection.[114]Oh ES, Laskin DM. Efficacy of the ViziLite system in the identification of oral lesions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007 Mar;65(3):424-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17307587?tool=bestpractice.com

[115]Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Lonky S, et al. The efficacy of oral lumenoscopy (ViziLite) in visualizing oral mucosal lesions. Spec Care Dentist. 2006 Jul-Aug;26(4):171-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16927741?tool=bestpractice.com

[116]Lane PM, Gilhuly T, Whitehead P, et al. Simple device for the direct visualization of oral-cavity tissue fluorescence. J Biomed Opt. 2006 Mar-Apr;11(2):024006.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16674196?tool=bestpractice.com

[117]Poh CF, Ng SP, Williams PM, et al. Direct fluorescence visualization of clinically occult high-risk oral premalignant disease using a simple hand-held device. Head Neck. 2007 Jan;29(1):71-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16983693?tool=bestpractice.com

[118]Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, et al. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006 Nov 15;12(22):6716-22.

http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/12/22/6716

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17121891?tool=bestpractice.com

However, oral lesions visualized with these optical adjuncts require formal biopsy to determine the underlying pathologic changes.

Photodynamic diagnosis (PDD) using 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA-PDD) enables the visualization of leukoplakia lesions as red fluorescence and has been shown to be successful in detecting oral disorders.[119]Tatehara S, Sato T, Takebe Y, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis using 5-aminolevulinic acid with a novel compact system and chromaticity analysis for the detection of oral Ccancer and high-risk potentially malignant oral disorders. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Jun 23;12(7):1532.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9321203

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35885438?tool=bestpractice.com

Compared with other optical systems, an improvement in the sensitivity and specificity to detect higher grades of dysplasia is described. However, more research is needed before recommending this for routine practice.

Molecular and chromosomal markers

The ability to predict malignant transformation subsequent to the establishment of a clinical and histologic analysis of premalignant conditions relates to identification of a set of molecular markers that are easily and economically applicable. These techniques are useful at the necessary routine follow-up visits following diagnostic workup.

Studies have yielded several molecular markers that are of potential value in helping predict future behavior of these lesions.[21]Zhang L, Rosin MP. Loss of heterozygosity: a potential tool in management of oral premalignant lesions? J Oral Pathol Med. 2001 Oct;30(9):513-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11555152?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Monteiro L, Mello FW, Warnakulasuriya S. Tissue biomarkers for predicting the risk of oral cancer in patients diagnosed with oral leukoplakia: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1977-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33290585?tool=bestpractice.com

For example, in assessment of leukoplakia involving so-called high-risk sites, there were greater levels of genetic alterations associated with an elevated risk of progression to carcinoma, by way of high losses of heterozygosity on chromosome 3p and/or 9p sites.[120]Zhang L, Cheung KJ Jr, Lam WL, et al. Increased genetic damage in oral leukoplakia from high risk sites: potential impact on staging and clinical management. Cancer. 2001 Jun 1;91(11):2148-55.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11391596?tool=bestpractice.com

Podoplanin, a transmembrane glycoprotein, could be a valuable biomarker in the future for risk assessment of malignant transformation in patients with oral leukoplakia.[121]de Vicente JC, Rodrigo JP, Rodriguez-Santamarta T, et al. Podoplanin expression in oral leukoplakia: tumorigenic role. Oral Oncol. 2013 June;49(6):598-603.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23473850?tool=bestpractice.com

Additionally, the development of gene array analysis technology and other molecular tools holds promise regarding the predictability of leukoplakia lesions progressing to a neoplastic phenotype.[122]Patel V, Leethanakul C, Gutkind JS. New approaches to the understanding of the molecular basis of oral cancer. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2001;12(1):55-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11349962?tool=bestpractice.com

DNA ploidy status remains an attractive option in evaluating oral leukoplakia where there has been demonstrated aneuploidy in associated increased risk of progression to squamous carcinoma.[23]Odell EW. Aneuploidy and loss of heterozygosity as risk markers for malignant transformation in oral mucosa. Oral Dis. 2021 Nov;27(8):1993-2007.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/odi.13797

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33577101?tool=bestpractice.com

Additionally, S-phase fractions of leukoplakia lesions with dysplasia demonstrated aneuploid rates more than double those of leukoplakias without dysplasia.[123]Khanna R, Agarwal A, Khanna S, et al. S-phase fraction and DNA ploidy in oral leukoplakia. ANZ J Surg. 2010 Jul-Aug;80(7-8):548-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20795971?tool=bestpractice.com

Further adding to the progress in understanding molecular carcinogenic changes in oral leukoplakia has been the addition of microarray analysis utilizing reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction results, with candidate biomarkers identified in those cases resulting in cancer formation.[124]Liu W, Zheng W, Xie J, et al. Identification of genes related to carcinogenesis of oral leukoplakia by oligo cancer microarray analysis. Oncol Rep. 2011 Jul;26(1):265-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21523324?tool=bestpractice.com

Salivary biomarkers

Novel noninvasive tests using saliva as a body fluid for the detection of biomarkers are in development. Human salivary proteome analysis using mass spectrometry, supported by bioinformatics tools, are reported. The most studied proteins S100A7, S100P, CD44, and COL5A1 have shown increased expression in leukoplakia as compared with healthy controls.[125]Sivadasan P, Gupta MK, Sathe G, et al. Salivary proteins from dysplastic leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma and their potential for early detection. J Proteomics. 2020 Feb 10;212:103574.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31706945?tool=bestpractice.com

Of these proteins, CD44 in oral rinses has been shown to have potential as a candidate marker for the early detection of oral cancer for patients who show leukoplakia lesions.[126]Franzmann EJ, Donovan MJ. Effective early detection of oral cancer using a simple and inexpensive point of care device in oral rinses. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2018 Oct;18(10):837-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30221559?tool=bestpractice.com

Several proangiogenic and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are also reported to be elevated in saliva samples of patients with oral leukoplakia, and elevated levels of these cytokines may indicate the carcinogenic transformation from precancer to oral cancer.[127]Goldoni R, Scolaro A, Boccalari E, et al. Malignancies and biosensors: a focus on oral cancer detection through salivary biomarkers. Biosensors (Basel). 2021 Oct 15;11(10):396.

https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6374/11/10/396

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34677352?tool=bestpractice.com

The ADA expert panel does not recommend vital staining, autofluorescence, tissue reflectance, or salivary adjuncts as triage tools for use in primary care.[93]Lingen MW, Abt E, Agrawal N, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of potentially malignant disorders in the oral cavity: a report of the American Dental Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2017 Oct;148(10):712-27;e10.

https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(17)30701-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28958308?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Speckled leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Speckled leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative verrucous leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Proliferative verrucous leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sublingual leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sublingual leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Candidal leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Candidal leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral hairy leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oral hairy leukoplakiaCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lip-cheek bitingCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lip-cheek bitingCourtesy of Dr James Sciubba; used with permission [Citation ends].