Approach

The main goals of treatment are:

The immediate management of the presenting bleeding[8]

The treatment of any underlying cause

The prevention of recurrence.[8]

Examination and treatment of epistaxis often proceeds concurrently.

Urgent considerations

Prompt assessment of bleeding severity will assist in directing the patient to the proper clinical site for management. Few studies address the most appropriate setting for care of nosebleeds.[8]

Generally, resuscitation is not required in most people presenting with epistaxis, but is required in the rare instance of hemodynamic compromise. Patients may be more prone to hemodynamic compromise if:

There is severe bleeding, indicated by a large volume of blood, prolonged bleeding, bleeding from both sides of the nose, or bleeding from the mouth

Severe bleeding may be more likely with a history of hospitalization for nosebleed, prior blood transfusion for nosebleed, or more than 3 recent nosebleeds.[8]

The patient is older

The patient is ill or frail

Comorbidities that may impede the patient's response to a bleed include hypertension, cardiopulmonary disease, anemia, bleeding disorders, and liver or kidney disease.[8]

Such patients need urgent resuscitation in the hospital.[8]

Oxygen supplementation, intravenous access, urgent complete blood count, platelets, clotting studies, and blood type for transfusion are required, along with the maintenance of airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC). These patients may present with:

Initial measures for acute active bleeding

Advise the patient to clear their nose of blood because blood clot may promote fibrinolysis.[8] They should hold their head in a "sniffing" position, flexed slightly forward.[8]

Then apply firm and sustained pressure to the lower third of the nose (the entire lower compressible cartilage) with or without assistance from a parent or caregiver for at least 5 minutes.[8] A nose clip can be used if available and tolerated by the patient.[8] Also, consider applying a topical vasoconstrictor (decongestant), such as oxymetazoline, using a nasal spray or by inserting impregnated cotton balls or pledgets into the nose.[8]

Apply the vasoconstrictor (decongestant) for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, to help visualize the epistaxis site and encourage hemostasis. Initial assessment may reveal an obvious underlying cause or exacerbating factor.

A decongestant will also shrink mucosal thickness, allowing more open nasal space should placement of a pack be required. This can reduce mucosal trauma incurred during insertion of a pack and thereby decrease secondary bleeding sites from disrupted mucus membrane.

Persistent bleeding precluding identification of a bleeding site

If you cannot identify the exact site of the bleeding, treat active bleeding that is not controlled by nasal pressure with nasal packing.[8][23] In most cases, this should be nonresorbable packing. With adequate resources, you can perform anterior nasal packing in outpatient offices or emergency departments.[8] See the section "Source visible, but cautery failing to control bleeding, or source not visible and not suspected to be posterior" below for details about nonresorbable nasal packing.

Demonstrates insertion of an inflatable anterior nasal pack and a nasal tampon.

For a patient with a suspected bleeding disorder, vascular abnormalities such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, a young child, or for a patient on antiplatelet medication or on an anticoagulant, use resorbable packing (that does not need to be removed).[8] A variety of resorbable materials is available, including oxidized regenerated cellulose, synthetic polyurethane sponge, chitosan-based materials, purified porcine skin and gelatin granules and hemostatic gelatin thrombin matrices, carboxymethylcellulose gel, hyaluronic acid, and carboxymethylcellulose.[8] Choose the specific packing based on local availability and experience; there is limited comparative evidence to support the use of one material over any other.[8]

Active bleeding persistent despite initial measures

Remove any blood clot (if present) because blood clot may promote fibrinolysis.[8] Perform anterior rhinoscopy with a nasal speculum (or otoscope, particularly in children) to identify any bleeding source on the anterior nasal septum, inferior and middle turbinates, floor of the nose, and anterior nasal mucosa.[8]

Consider applying a combination of topical anesthetic (e.g., lidocaine) and vasoconstrictor (decongestant) at this stage.[8] Topical anesthetic makes the procedure more comfortable for the patient and less stressful for the physician. Some physicians prepare a mixture of anesthetic and decongestant in the office or emergency department. For the decongestant, use oxymetazoline rather than phenylephrine as the latter seems more likely to cause hypertension or possibly angina in susceptible patients. Some physicians simply remove the top from a spray bottle of oxymetazoline, add an equal volume of the lidocaine, and replace the top; however, seek specialist advice.

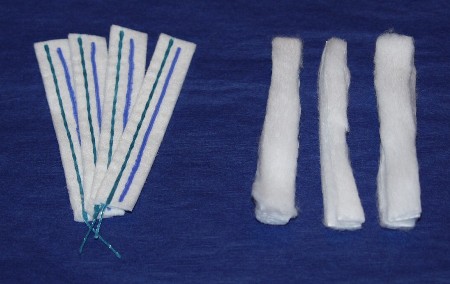

Active bleeding may necessitate the rapid alternation between clearing of blood and liberal application of the topical vasoconstrictor and anesthetic. Next, place small neurosurgical pledgets or strips of cotton well saturated with the mixture horizontally in the nose with bayonet forceps, and leave for 10 to 15 minutes. Ask the patient to compress their nose if necessary. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nasal pledgets for application of decongestant and local anestheticFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

Underlying causes, such as septal deviation or perforation, may become apparent at this stage.[8] Treat local causes such as foreign body, polyp, and ulceration to the skin around the nose accordingly.[27]

Persistent or recurrent bleeding

If the bleeding site is not visible with simple anterior rhinoscopy, the attending physician may perform nasal endoscopy; alternatively it may require referral to a clinician with the relevant expertise.[8] Studies suggest successful localization of the bleeding point in 87% to 98% of cases, and initial endoscopy-guided treatment success rates of about 93%.[28]

Perform nasal endoscopy for patients with a high risk of having a posterior bleeding source, an underlying pathology, or with recurrent unilateral bleeding (particularly if associated with unilateral nasal obstruction).[8]

Consider nasal endoscopy if bleeding is difficult to control, or if additional nasal symptoms exist that may indicate an unrecognized pathology.[8]

Nasal malignancies present with epistaxis in 55% of cases and unilateral nasal obstruction in 67% of cases. These tumors may not be visible on anterior rhinoscopy, but while rare, a delay in diagnosis can result in life-threatening hemorrhage.[8]

Bleeding source visible

Treat patients with an identified bleeding site with one or more of the following options, as appropriate: topical vasoconstrictors (including oxymetazoline, phenylephrine, epinephrine, or cocaine), nasal cautery, and moisturizing or lubricating agents.[8] Moisturizing and lubricating agents would not likely be used for an active bleed, but would most commonly be used after cessation of bleeding following cautery and/or vasoconstrictors.[8]

Combinations of several methods are often used; with little evidence comparing options, the American Academy of Otolaryngology guideline refrains from recommending a specific order for these interventions.[8]

The American Academy of Otolaryngology guideline recognizes that the British Rhinological Society recommends that vasoconstrictors should be used prior to cautery, and that cautery of an identified bleeding site should be first-line treatment; however the US guideline notes that these recommendations were based on limited evidence.[28]

Give oxymetazoline and phenylephrine as an intranasal spray or on a cotton pledget, but be cautious in patients with hypertension, cardiac disease, or cerebrovascular conditions, as vasoconstrictors may be associated with cardiac and other complications.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology guideline does not specify a preference for either the chemical or electrical method of cautery.[8] Silver nitrate, chromic acid, or trichloroacetic acid can be used for chemical cautery.[8] However, electrocautery is suggested to be more effective than chemical cautery if the relevant resources and expertise are available.[28]

Perform electrocautery for brisker bleeding that is resistant to silver nitrate treatment. This procedure is usually reserved for the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist. It requires injection of local anesthetic plus vasoconstrictor (e.g., lidocaine with epinephrine), in addition to topical anesthetic. Monopolar and bipolar cautery are both effective. Suction monopolar cautery (if available) evacuates blood and enhances effect, as cautery is ineffective in a wet, blood-filled field. Provide routine post-treatment instructions.

Although most frequently used for office treatment of recurrent epistaxis when bleeding is quiescent, use silver nitrate cautery to treat minor anterior active epistaxis if you have identified a specific site.

Silver nitrate is applied via commercially manufactured sticks or applicators. This compound degrades over time and must be kept in an airtight, lightproof container. Lack of evident activity may indicate the need to use fresher silver nitrate.

Anesthetize the bleeding site adequately; recommendations do not specify a preference for topical or injected anesthetic agents.[8] Lidocaine or tetracaine are common options.[8] Lidocaine can be injected into the nasal septum or administered topically via spray or on pledgets.[8]

Apply the cauterizing agent to specific vessels or hemorrhagic areas of concern, and remove excess with a cotton tip applicator.

The patient may find treatment uncomfortable even with adequate topical vasoconstrictor and anesthetic.

Apply petroleum jelly afterward for moisturization.

Avoid cautery at the same location on both sides of the septum. This deprives the septal cartilage of its blood supply (from the mucosal covering) and may result in septal perforation if done bilaterally.

Source visible, but cautery failing to control bleeding, or source not visible and not suspected to be posterior

Use anterior nasal packing for active bleeding when you cannot visualize the source or cautery has been ineffective. There are 2 types of packing method, traditional packing and a variety of gauze dressings, polymers, and inflatable balloons available in different sizes.[8]

Traditional packing involves horizontal layering of 12-mm (half-inch) cotton gauze saturated with petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment to facilitate insertion with minimal mucosal trauma.[8] The newer options are more convenient and easier to position than traditional packing, particularly for physicians who infrequently place nasal packing. Because of concerns that packing material may become displaced, some patients are managed in the hospital, but uncomplicated patients with nosebleeds controlled with nonresorbable anterior packing can usually be managed as outpatients, depending on local protocols.[8][30] Remove all types of nonresorbable packings at some point after achieving sustained control of nasal hemorrhage.[8] The pack is usually removed at 48-72 hours.[8] This allows:

Healing of the original bleeding site

Remucosalization of any secondary sites from pack insertion trauma

Regeneration of functional platelets or clotting factors in patients on medications that impair coagulation.

As epistaxis generally originates on one side, packing is unilateral. Bilateral packing is only indicated in the unusual situation of true hemorrhage from both sides, or when the history and examination fail to identify whether the bleeding is from the right or the left. In practice, nonspecialists often resort to bilateral packing as it is difficult to determine accurately the true site of the bleed.

Although controversial, consider oral antibiotics on an individual basis while resorbable and nonresorbable packing remains in place, because impaired sinus drainage and aeration increases risk of infection.[8] The blood saturated pack can (though rarely does) result in toxic shock syndrome.[8] Antimicrobials have potential for benefit with minimal risk. Select antibiotics that have activity against typical sinusitis pathogens and Staphylococcus aureus.[8] Appropriate antibiotics include trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin/clavulanate, or cefuroxime. Use a macrolide or fluoroquinolone in the case of allergy to penicillin or cephalosporins.

Prescribe analgesics, as appropriate, for discomfort. A combination of acetaminophen/hydrocodone, or similar, is recommended. Avoid aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Details of traditional gauze anterior nasal pack

For traditional packs, both dry and petroleum jelly-saturated gauze are available.

Although there is little evidence of protective benefit from toxic shock syndrome by application of topical antibiotic ointment, its use to lubricate packing and reduce trauma is reasonable and commonplace.[8] Mupirocin ointment has an effect against Staphylococcus aureus, a strain of which is responsible for toxic shock syndrome, so it is often used. The gauze may be generously coated with antibiotic ointment or bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (BIPP) in place of plain petroleum jelly.

Layer the gauze horizontally with bayonet forceps, first along the floor of the nose and successively superiorly to fill the nose.

Compress each layer of packing downward after placement to increase pressure on the nasal cavity walls. Depending on nasal size, 2 m (72 inches) or more may be required for one side of the nose. Following placement, the lower, cartilaginous portion of the nose appears distended.

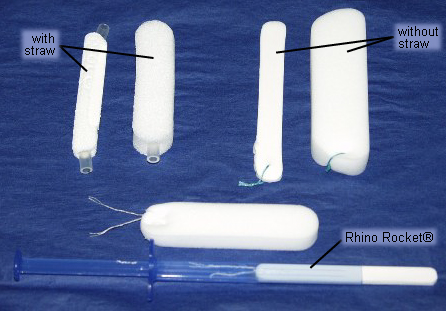

Details of expanding nasal sponge packing

Ease and rapidity of placement has encouraged the popularity of expanding nasal sponges. These are manufactured with and without a longitudinal tube or straw. Those without the tube are typically 2 to 3 mm thick in compressed form, though they expand to up to 1 cm when saturated with fluid. The straw increases dry thickness to about 5 mm. Manufacturers provide a variety of shapes and lengths. The 1 cm x 8 cm or 10 cm sizes work well in most cases. The longitudinal tube is intended to decompress the nasopharynx to prevent uncomfortable pressurization when the soft palate elevates during swallowing with bilateral packing. Their greater thickness has the disadvantage of potentially increased difficulty, pain, and mucosal excoriation during placement. Certain sponge packs are available with a syringe-type applicator (e.g., the "Rhino Rocket"). This type of device is popular due to its ease of placement, though it has less expanded thickness than some other packs and may provide less effective mucosal pressure. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Expanding nasal sponge tamponsFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

To insert the expanding sponge:

Inspect the nose for septal deviation that may impair placement; forcing a pack along a septal spur or deflection can result in mucosal injury and bleeding from these secondary sites

Trim the sponge pack as necessary and coat with petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment; then slide the pack posteriorly in the nose with bayonet forceps

In the case of a horizontal septal spur or deflection, trim the pack longitudinally, and place the 2 pieces separately above and below the spur. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Expanding nasal sponge pack in placeFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

Anterior packing failing to control bleeding, or posterior source suspected

Perform posterior packing in an emergency department or hospital setting. Care of patients requiring this level of packing should involve an otolaryngology attending.[8]

Anterior-posterior nasal packing is indicated:

For known posterior bleeding

In case of failure of a properly placed anterior pack to control hemorrhage.

Use anterior packing to reinforce posterior packing; the pressure at the posterior choanal area prevents anterior blood flow. Consider intravenous analgesia (an opioid) and an antiemetic because of the greater patient discomfort associated with this packing. Use opioids with caution in older and shocked patients.

A variety of posterior pack options exist, though the methods described below provide both effectiveness and ease of placement. These are:

The double-balloon epistaxis device

The traditional gauze anterior pack with the Foley urinary catheter placed posteriorly.

Details of double-balloon epistaxis device

Commercially available, double-balloon catheters have a 15 mL distal balloon (similar to that of a Foley catheter) for the posterior packing component, and a proximal 30 mL balloon to provide anterior packing and occlude the nostril. Their popularity lies in their relative ease of placement and allows a nonspecialist clinician to insert them.[8] Disadvantages include thickness and rigidity of their shafts (which may prevent passage through a narrow nasal cavity) and potentially less effective pressure on the nasal mucosa. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Deflated and inflated double-balloon nasal catheterFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

Deployment of these devices includes:

Lubrication with petroleum jelly, antibiotic ointment, or water-based lubricant jelly

Insertion, such that the distal balloon enters the nasopharynx

Inflation of the distal balloon (typically with 7 to 8 mL of water), pulling it forward to lodge in the posterior choana

Filling the anterior balloon with about 15 mL of water until it occludes the nostril.

Place padding between the external portion of the catheter and the nostril with great care. This provides anterior traction to keep the distal balloon positioned and averts direct catheter pressure on tissue which can cause significant cosmetic deformity from alar and columellar notching. A piece of gauze wrapped around the shaft between the nose and the Y-junction of the catheter works well. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Double-balloon nasal catheter in placeFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

If the double-balloon catheter fails to control bleeding, replacement with a traditional anterior-posterior pack may be necessary. Alternatively, a narrowed nasal cavity from septal deviation may preclude passage of the thicker double-balloon catheter, and require use of a thinner, more flexible Foley catheter.

Details of traditional gauze anterior pack with the Foley urinary catheter placed posteriorly

The Foley-type urinary catheter is probably the easiest means of placing a traditional anterior and posterior pack.

Lubricate a size 12 French catheter with petroleum jelly, antibiotic ointment, or water-based lubricant jelly.

Pass it into the nasopharynx, and then inflate the balloon with 7 to 8 mL of water.

Position and lodge the balloon in the posterior nasal choana with anterior traction on the catheter.

Ask an assistant to maintain a steady anterior pull on the catheter to maintain its position, while you insert a traditional gauze pack as described above into the anterior nasal cavity.

Use a piece of gauze, wrapped around the catheter shaft, as padding to prevent pressure necrosis at the nostril. Use silk tape, wrapped around this bolster, to maintain its shape.

Secure an umbilical clamp against the bolster with adequate tension to keep the balloon in the posterior choana.

Tie several silk sutures around the catheter shaft in front of the umbilical clamp to prevent leakage of water from the catheter. Then trim excess shaft length for patient comfort.

Prescribe similar analgesics and antibiotics as you would for anterior packing. Select antibiotics that have activity against typical sinusitis pathogens and Staphylococcus aureus.[8] Appropriate antibiotics include trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin/clavulanate, or cefuroxime. Use a macrolide or fluoroquinolone in the case of allergy to penicillin or cephalosporins.

Analgesics such as acetaminophen/hydrocodone are recommended. Avoid aspirin and NSAIDs. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Anterior-posterior traditional Foley catheter-gauze packFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

There has been concern about posterior packs causing hypoxia, and the need for intensive cardiorespiratory monitoring while the packs remain in place.[8] Some authors recommend observation of patients in the intensive care unit while posterior packing is in place, while others feel that this is appropriate specifically for older people and patients with comorbidities.

Further analgesia and local anesthetic

Nasal packing remains uncomfortable, even with good topical anesthesia. If an intravenous line is available, use parenteral opioid analgesia, particularly with posterior packing of the nose. Use opioids with caution in older and shocked patients.

Pretreatment with an antiemetic avoids nausea and emesis. Ondansetron avoids sedation associated with medications such as promethazine.

Ketorolac should not be used as it will impair platelet formation.

Lidocaine with epinephrine may be infiltrated in the vicinity of a bleeding site. There is hemostatic benefit from the epinephrine and possibly from hydrostatic tissue pressure of the infiltrated volume of medication. This method is a requirement before electrocautery is undertaken but may be used with other treatments.

Posterior analgesia and vasoconstriction may be facilitated by local anesthetic infiltration into the greater palatine foramen. This block technique should be used with caution and only in experienced hands because it is painful and has the rare potential for blindness. This is rarely used.

Nasal pack removal

After nasal packing in the emergency department or primary care physician's office, arrange otolaryngology follow-up for nasal endoscopy and more thorough examination if warranted. Referral to the otolaryngology department for nasal pack removal may be valuable as the otolaryngology office is more likely than the primary care physician's office to have necessary items for management of any rebleeding should it occur.

Remove packing after 2 to 3 days to allow healing of the original and possibly secondary (from excoriation of packing placement) bleeding sites.[8] This also allows patients taking anticoagulant-type drugs time to generate clotting factors.

Apply a mixture of topical vasoconstrictor (oxymetazoline) with lidocaine to the sponge pack to facilitate removal. Saturate the pack to promote pack softening and lubrication, shrinking of the adjacent mucosa via vasoconstriction, and to provide some analgesia. This seems to discourage mucosal trauma and rebleeding with pack removal.

Consider cautery (usually silver nitrate) for suspicious vessels or friable, hemorrhagic sites following pack removal.[27]

Persistent bleeding despite anterior and posterior nasal packing

Nasal packing and cautery will successfully treat most nosebleeds. Various procedures may be used to manage persistent bleeding. The choice will depend on availability of appropriate resources and expertise:[8][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

Endoscopic management of epistaxis sites

Angiography and embolization with interventional radiology

Open surgical arterial ligation.

An advantage of endoscopic arterial ligation is that concurrent endoscopic sphenopalatine artery (SPA) and anterior ethmoidal artery ligation can be performed; however, the need for general anesthesia is a disadvantage.[8] Advantages of embolization include the ability to perform the procedure under sedation, avoid trauma to the nasal mucosa, and leave packs in place, but there is some risk of occlusion of adjacent vessels and the potential for cerebrovascular accident.[8] A sequential approach of transnasal endoscopic SPA ligation (TESPAL) followed by endovascular embolization for epistaxis that does not respond to packing has been suggested.[8][38]

Endoscopic management of epistaxis sites

The advent of rigid nasal endoscopy has greatly improved visualization and access to the nose. Endoscopic identification and guided electrocautery to posterior bleeding sites have become more common and an effective alternative to nasal packing.[8] Suction cautery under direct visualization may control some nosebleeds located posteriorly. Similarly, surgical dissection and surgical clip ligation of the SPA may be accomplished under direct endoscopic vision.[33][34] SPA ligation is the mainstay of treatment when conservative management of posterior epistaxis has failed.[39] It is usually performed under a general anesthetic but can be accomplished under sedation with local anesthetic.

Angiography and embolization with interventional radiology

This procedure offers another means of interrupting the arterial supply, avoiding the need for surgery. If contemplating this technique, try it before transantral ligation because the latter often occludes access vessels necessary for successful embolization.[36][37][40]

Endovascular embolization is appropriate for treating posterior epistaxis and involves embolization of the bilateral sphenopalatine/distal internal maxillary arteries. Sometimes, the facial arteries require embolization if there are anastomoses with the SPA via the infraorbital artery and alar and septal branches from the anterior nasal compartment.[8]

Obtain detailed prior angiography (including internal and external carotid arteries) because blindness and stroke are serious complications that, although rare, occur more frequently than in patients undergoing surgical arterial ligation. Endovascular embolization of the anterior and/or posterior ethmoid arteries is contraindicated, because of the risk of blindness.[8]

Open surgical ligation

Open surgical ligation is rarely required, but may be indicated when endoscopic surgery or angiography with embolization have failed or are not available. Two approaches are as follows.

Transantral vessel ligation: this is the traditional means for surgical control of vessels feeding the nasal cavity, though it has been largely superseded by TESPAL.[8] Access is obtained by a sublabial approach and removal of both anterior and posterior walls of the maxillary sinus. This approach provides access to the internal maxillary vessels, which are ligated with surgical vascular clips. Simple ligation of the external carotid artery fails due to extensive collateral flow among regional vessels and contralateral connection.

A traditional external approach to ligate the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries may stop bleeding from high in the nose. A Lynch incision at the lateral aspect of the nasion medial to the upper lid and medial canthus provides surgical access.[4][31][32][35][36] Given the risks of ligating the posterior ethmoid artery due to its closeness to the optic canal, some surgeons opt to ligate only the anterior ethmoid artery.

Peripheral intravascular catheter: animated demonstrationHow to insert a peripheral intravascular catheter into the dorsum of the hand.

Recurrent but quiescent epistaxis

The patient may present with recurrent epistaxis that is not currently active. This is a common scenario in children. Silver nitrate cautery may be used.[8] Patients may have a history of bleeding from both sides of the nose. If so, determine which side has the worst bleeding, as this would be the side selected for cautery. It is important to avoid cautery at the same location on both sides of the septum. This deprives the septal cartilage of its blood supply (from the mucosal covering) and may result in septal perforation if done bilaterally. Defer similar treatment of the other side for about 4 weeks until the initial cautery site has healed.

Younger children may not tolerate simple office cautery even with good topical anesthesia and occasionally require brief general anesthetic.

Silver nitrate cautery has been compared with antiseptic creams in children with recurrent epistaxis.[42][43] One Cochrane review of interventions in children is inconclusive, but does suggest that if silver nitrate cautery is used, a 75% preparation may be more effective and less painful than 95%.[42] Petroleum jelly has been compared with no treatment.[42] The evidence for antiseptic creams and petroleum jelly is still limited, and high-quality randomized controlled trials with longer follow-up periods are required.[42] A late double-blind study suggests that silver nitrate cautery plus antiseptic cream confers greater benefit than antiseptic cream alone.[44]

Recurrent episodes may also occur in people with coagulation disorders, neoplasms, and familial hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Neoplasm requires treatment of the underlying tumor. Preoperative embolization reduces blood loss in some cases: for example, juvenile nasal angiofibroma.[11]

Patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia have a lifelong proclivity for bleeding from dilated, fragile mucosal vessels. Periodic prophylactic silver nitrate, electrocautery, or laser treatment may ablate vessels. On occasion, the nasal septum is re-lined with a skin graft (septal dermoplasty).[19][20][45] Coagulation disorders require management depending on the underlying cause and may need to be corrected with transfusion of platelets, or clotting factors.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer