Approach

Diagnosis of epistaxis is usually readily apparent, as the patient presents with bleeding from the nose. Be careful to differentiate between epistaxis, hematemesis, and hemoptysis.

Assemble equipment and other necessary treatment before starting the examination, so that you can examine and treat the patient concurrently.

Preparation for assessment and treatment of acute epistaxis

Appropriate equipment remains key for the assessment and treatment of epistaxis. Prepare for patient assessment by:

Donning gloves, safety glasses, and protective clothing.

Covering the patient's clothing with a gown to avoid staining.

Giving the patient a large bucket or basin and nasal tissues to catch blood.

Asking the patient to sit upright and incline their head forward in a "sniffing" position.[8]

Pinching for 5 minutes or longer the entire lower cartilage portion of the nose to compress a potential anterior bleeding source.[8]

Asking the patient to blow the nose to clear the nasal airway of clot, or by using gentle suctioning.[8]

Using a headlight and suction (12 French Frazier tip suction).

Applying a local anesthetic mixed with a vasoconstrictor to slow bleeding and facilitate inspection of the nose.

Identifying any bleeding point that may be amenable to immediate application of silver nitrate cautery.

Urgent considerations

Although epistaxis is almost always a localized process, remember that, in very rare cases, anemia or hypovolemia may occur. Promptly assess bleeding severity and direct the patient to the proper clinical site for management.[8] Few studies address the most appropriate setting for care of nosebleeds.[8]

Be aware that patients may be more prone to hemodynamic compromise if:

There is severe bleeding, indicated by a large volume of blood, prolonged bleeding, bleeding from both sides of the nose, or bleeding from the mouth

Severe bleeding may be more likely with a history of hospitalization for nosebleed, prior blood transfusion for nosebleed, or more than 3 recent nosebleeds.[8]

The patient is older

The patient is ill or frail

Comorbidities that may impede the patient's response to a bleed include hypertension, cardiopulmonary disease, anemia, bleeding disorders, and liver or kidney disease.[8]

Resuscitate such patients urgently in the hospital.[8] Supplement oxygen, establish intravenous access, obtain blood for an urgent complete blood count (CBC), clotting studies, and blood type for transfusion, and maintain the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC). These patients may present with:

Generally, these measures are not required in most people presenting with epistaxis.

Presence of risk factors

Document factors that increase the frequency or severity of a nosebleed including a personal or family history of a bleeding disorder, anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication, or intranasal drug use.[8]

Other risk factors strongly associated with epistaxis include prior nasal or sinus surgery, nasal or facial trauma, nasal cannula oxygen use, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) use, intranasal medication or illicit drug use, medications that impair coagulation and/or platelet function, chronic kidney or liver disease, dry weather, low humidity, oxygen dependence, mechanical irritation to the nose, nose picking, intranasal foreign bodies, and trauma to the nose or face.[8] Patients may be taking medications, including herbal remedies,[21] that delay clotting or that interfere with anticoagulant drugs. Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin are a risk factor for epistaxis, and patients taking aspirin require more frequent surgical intervention to stop bleeding.[8][18]

Epistaxis may be weakly associated with forceful coughing, barotrauma, and environmental irritants.

Enquire about other nasal-related symptoms that might suggest bacterial infection or nasal polyps.

Be aware that epistaxis may occasionally be associated with granulomatous conditions such as sarcoid and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Although epistaxis is associated with hypertension, a causative role has not been established.

History and clinical presentation of acute epistaxis

Identify the site of the bleeding:

Patients often present with blood in both sides of the nose, as well as dripping from the nostril and down the back of the throat.

On which side did the bleeding first start, and did it come from the anterior nares (suggesting anterior site), or from the throat (suggesting posterior site)?

If occurring during sleep or when supine, most or all of the blood drains to the throat, whether originating from the front or back of the nose.

Although patients may feel that bleeding originates high up or back in the nose, remember that 90% of nosebleeds occur from the anterior septum despite the patient's history.

Note the presence of any septal deviation. This may increase the risk of epistaxis, either on the side of the deviation (by making the septal mucosa more exposed), or on the opposite side (mucosa may become dried if this nostril provides most of the airflow). Septal deviation may also make nasal packing placement more difficult.

Identify cause of bleeding:

Consider risk factors strongly associated with epistaxis.

Think about neoplasm (extremely rare cause of nosebleed); this may be suggested by hypoesthesia in the distribution of the second branch of the trigeminal nerve, or by pain at the lesion or in the same distribution.

Examination in acute epistaxis

Ask the patient to gently blow their nose to clear old blood and large clots.

Examine the patient with headlight and nasal speculum (anterior rhinoscopy) using nasal suctioning with Frazier suction to facilitate viewing. In the absence of nasal speculum, simply elevate the tip of the nose with a finger to give a reasonable view of the front of the nasal cavity.

Active bleeding may prevent evaluation. In this case, mucosal vasoconstriction (decongestion) is helpful both diagnostically and therapeutically. Apply a topical vasoconstrictor, such as oxymetazoline.[8] Sometimes bleeding prevents administration into the nose. Rapidly alternate nasal suction (or nose blowing) and intranasal spraying of this medication.

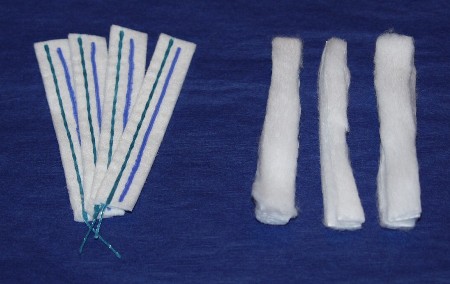

Alternatively, generously apply the vasoconstrictor to strips of cotton or neurosurgical pledgets.[8] Place them in the nose after initially using the nasal spray. Typically use 3 cotton strips or pledgets per side. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Nasal pledgets for application of decongestant and local anestheticFrom the collection of David A. Randall, Springfield Ear Nose Throat and Facial Plastic Surgery, MO [Citation ends].

For patient comfort during subsequent examination and treatment, include a topical anesthetic. If a bleeding source is visible, local treatment may be possible. If a source is not visible, perform nasal packing.

If you suspect posterior epistaxis, examine the posterior nasal cavities and nasopharynx with either a rigid 4 mm, 0-degree endoscope, or a flexible fiberoptic rhinolaryngoscope, depending on your experience with each procedure. The rigid scope may be more difficult to pass if there is a septal deviation, but an ear, nose, and throat specialist can use the rigid scope for treatment with one hand, while suctioning with the other hand.

Investigations for acute epistaxis

Laboratory investigations are not usually necessary, although they may be required in certain specific circumstances:

Obtain hematocrit or CBC if you are concerned about anemia from excessive blood loss or any clotting abnormality.

Request coagulation studies (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, platelet function tests) only if the bleeding is unusually persistent, unreponsive to treatment, or recurrent.[8]

Investigate blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and liver function tests only if you are concerned about the patient's general medical condition. Impaired liver or kidney function may result in impaired clotting.

Imaging is also not normally necessary but is indicated, following control of bleeding, in specific circumstances:

If you suspect a tumor, obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head to differentiate between soft-tissue of neoplasm and fluid (e.g., blood or mucus).

Request a computed tomography (CT) scan of the paranasal sinuses when epistaxis is secondary to facial trauma. Bony structures may be viewed clearly with axial and coronal facial CT scan. Use contrast with CT scan if you suspect a tumor; however, this type of imaging is not as good as MRI because it shows only intermediate density for both tissue and fluid. Therefore, it is often unable to differentiate sinusitis from neoplasm.

Plain sinus x-rays yield little information except the nonspecific finding of sinus opacification, and are generally not recommended. Rarely, the late finding of bony erosion or displacement from tumor might be found.[1][2][3][4][10]

Further specialist investigations for acute epistaxis

Not only are nasal endoscopy and nasopharyngoscopy indicated when an obvious epistaxis source has not been seen, but they are also used to examine for the presence of a tumor. When performed by a trained specialist, they also provide the opportunity for therapeutic intervention in the form of endonasal cautery or laser ablation (laser for vessels from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia). If more than simple anterior or midnasal cautery is needed, then the procedure requires a general anesthetic or intravenous sedation.

Consider internal and external carotid angiography for refractory and complicated epistaxis that persists after otolaryngology involvement. It is indicated if there is persistent epistaxis despite nasal packing. Blood supply to the nose is displayed and vascular anomalies may be identified. The procedure allows interventional embolization of feeder vessels.

Recurrent epistaxis

The patient may present with recurrent epistaxis that is not currently active. This is a common scenario in children. Patients may have a history of bleeding from both sides of the nose. If so, determine which side has the worst bleeding, as this would be the side selected for cautery. Defer similar treatment of the other side for about 4 weeks until the initial cautery site has healed.

Take a thorough history about coagulation disorders, neoplasms, and familial hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in people with recurrent episodes of nosebleed and investigate, as described for the situation of acute epistaxis.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer