Four inherited defects of bilirubin metabolism are recognized. Gilbert syndrome and Crigler-Najjar syndrome (type I and II) are associated with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. DJS and Rotor syndrome result in conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[28]Erlinger S, Arias IM, Dhumeaux D. Inherited disorders of bilirubin transport and conjugation: new insights into molecular mechanisms and consequences. Gastroenterology. 2014 Jun;146(7):1625-38.

https://www.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.03.047

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24704527?tool=bestpractice.com

Both DJS and Rotor syndrome have a relatively benign course.

Diagnosis is important to avoid unnecessary investigations and alleviate concern. Other causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, such as benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis, may present with symptoms in addition to jaundice and show evidence of progressive liver damage at presentation. This is unusual in DJS or Rotor syndrome.

History

The diagnosis of DJS should be considered in a well patient with a history of jaundice. It may be intermittent with noticeable exacerbations following infection, intercurrent illness, pregnancy, or during the use of oral contraceptives. It is postulated that reduction of hepatic excretory function induced by sex steroids can transform mild hyperbilirubinemia into frank jaundice.[5]Rastogi A, Krishnani N, Pandey R. Dubin-Johnson syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of twenty cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006 Oct;49(4):500-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17183837?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Shani M, Seligsohn V, Gilon E, et al. Dubin-Johnson syndrome in Israel: clinical, laboratory and genetic aspects of 101 cases. Q J Med. 1970 Oct;39(156):549-67.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5532959?tool=bestpractice.com

Stress is also a possible trigger.[3]Dubin IN. Chronic idiopathic jaundice: a review of 50 cases. Am J Med. 1958 Feb;24(2):268-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13508683?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients usually have few other symptoms. Vague abdominal pain and fatigue has been reported, although this is not consistent and does not correlate with severity of underlying pathology.[1]Dubin IN, Johnson FB. Chronic idiopathic jaundice with unidentified pigment in the liver cells: a new clinicopathologic entity with report of 12 cases. Medicine. 1954 Sep;33(3):155-97.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13193360?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Sprinz H, Nelson RS. Persistent nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemia associated with lipochrome-like pigment in liver cells: report of 4 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1954 Nov;41(5):952-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13208040?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dubin IN. Chronic idiopathic jaundice: a review of 50 cases. Am J Med. 1958 Feb;24(2):268-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13508683?tool=bestpractice.com

By contrast with syndromes associated with true cholestasis, there is no pruritus.[5]Rastogi A, Krishnani N, Pandey R. Dubin-Johnson syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of twenty cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006 Oct;49(4):500-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17183837?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Junge N, Goldschmidt I, Wiegandt J, et al. Dubin-Johnson Syndrome as differential diagnosis for neonatal cholestasis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021 May 1;72(5):e105-11.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000003061

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33534365?tool=bestpractice.com

Typically patients are between the ages of 10 and 30 years when a diagnosis is made.[5]Rastogi A, Krishnani N, Pandey R. Dubin-Johnson syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of twenty cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006 Oct;49(4):500-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17183837?tool=bestpractice.com

Rarely, DJS may present in neonates. DJS is more common in males and in Iranian or Moroccan Jews.[15]Shani M, Seligsohn V, Gilon E, et al. Dubin-Johnson syndrome in Israel: clinical, laboratory and genetic aspects of 101 cases. Q J Med. 1970 Oct;39(156):549-67.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5532959?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Zlotogora J. Hereditary disorders among Iranian Jews. Am J Med Genet. 1995 Jul 31;58(1):32-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7573153?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Mor-Cohen R, Zivelin A, Fromovich-Amit Y, et al. Age estimates of ancestral mutations causing factor VII deficiency and Dubin-Johnson syndrome in Iranian and Moroccan Jews are consistent with ancient Jewish migrations. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007 Mar;18(2):139-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17287630?tool=bestpractice.com

There may be a positive family history.

Exam

Yellow discoloration of the skin, sclera, and mucous membranes confirms jaundice. Hepatomegaly may be present. General exam may reveal features of an intercurrent illness or infection, but signs are not specific to DJS. The presence of other signs of liver disease such as tender hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, white nails due to hypoalbuminemia, clubbing, or easy bruising suggest an alternative cause for jaundice.

Laboratory findings

All patients with jaundice of unknown etiology should undergo a full set of liver function tests (LFTs) and a clotting profile. There is usually elevation of conjugated bilirubin in serum, but other LFTs such as aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase are usually normal.[29]Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Jan;112(1):18-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27995906?tool=bestpractice.com

This helps to differentiate between DJS and extrahepatic biliary obstruction.[30]Bar-Meir S, Baron J, Seligson U, et al. 99mTc-HIDA cholescintigraphy rotor in Dubin-Johnson syndromes. Radiology. 1982 Mar;142(3):743-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7063695?tool=bestpractice.com

Occasionally, there may be a mild elevation of alanine aminotransferase (<2 times the upper limit of normal).[31]Al-Hussaini A, AlSaleem B, AlHomaidani H, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and molecular characterization of neonatal-onset Dubin-Johnson syndrome in a large case series from the Arabs. Front Pediatr. 2021 Nov;9:741835.

https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.741835

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34858902?tool=bestpractice.com

Typically the total bilirubin values are in the range of 2 to 5 mg/dL, with increased plasma conjugated bilirubin.[32]Talaga ZJ, Vaidya PN. Dubin Johnson syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536994

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30725679?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum bile acids are usually normal in contrast to some cholestatic disorders that also present with a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[33]The familial conjugated hyperbilirubinemias. Semin Liver Dis. 1994 Nov;14(4):386-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7855632?tool=bestpractice.com

Occasionally mild elevations in bile acids may be seen. Clotting times are not affected.

Subsequent investigations

The diagnosis is suggested by demonstrating an increase in the ratio of urinary coproporphyrin I to coproporphyrin III. Coproporphyrins are by-products of heme biosynthesis. Coproporphyrin I is usually excreted in bile, whereas coproporphyrin III is preferentially excreted in urine. In DJS, more than 80% of the coproporphyrin excreted is type I.[5]Rastogi A, Krishnani N, Pandey R. Dubin-Johnson syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of twenty cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006 Oct;49(4):500-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17183837?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]The familial conjugated hyperbilirubinemias. Semin Liver Dis. 1994 Nov;14(4):386-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7855632?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Frank M, Doss M, de Carvalho DG. Diagnostic and pathogenetic implications of urinary coproporphyrin excretion in Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990 Feb;37(1):147-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2312040?tool=bestpractice.com

Total coproporphyrin levels can be increased in patients with various hepatobiliary disorders, but this alteration in the ratio is unique to DJS.[5]Rastogi A, Krishnani N, Pandey R. Dubin-Johnson syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of twenty cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006 Oct;49(4):500-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17183837?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]The familial conjugated hyperbilirubinemias. Semin Liver Dis. 1994 Nov;14(4):386-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7855632?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Frank M, Doss M, de Carvalho DG. Diagnostic and pathogenetic implications of urinary coproporphyrin excretion in Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990 Feb;37(1):147-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2312040?tool=bestpractice.com

Healthy neonates have been shown to have impressive elevations of urinary coproporphyrin levels, with more than 80% being isomer I during the first 2 days of life; but by day 10, the levels fall to overlap with normal adult values.[33]The familial conjugated hyperbilirubinemias. Semin Liver Dis. 1994 Nov;14(4):386-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7855632?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Rocchi E, Balli F, Gibertini P, et al. Coproporphyrin excretion in healthy newborn babies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984 Jun;3(3):402-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6737185?tool=bestpractice.com

Cholescintigraphy

A 99mTc hepatobiliary imino-diacetic acid scan (cholescintigraphy) can be useful if the diagnosis is unclear or if other conditions are suspected.[30]Bar-Meir S, Baron J, Seligson U, et al. 99mTc-HIDA cholescintigraphy rotor in Dubin-Johnson syndromes. Radiology. 1982 Mar;142(3):743-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7063695?tool=bestpractice.com

The uptake of the radionuclide 99mTc by the liver is excellent, but the excretion from the liver into the biliary tract is impaired. A unique cholescintigram is obtained, showing intense and prolonged visualization of the liver with delayed visualization of the gallbladder and common bile duct. This pattern is different from that seen in patients with hepatocellular disease, extrahepatic biliary obstruction, or Rotor syndrome.

Liver biopsy

A percutaneous liver biopsy is recommended for some patients with suspected DJS to establish the diagnosis and exclude more serious liver pathology. Normal liver histology and the characteristic parenchymal deposition of a melanin-like pigment is diagnostic. Alternatively, a dark liver may be noted during surgery for another cause, prompting a liver biopsy. (Urinary coproporphyrin is a surrogate marker, rather than a definitive test. DJS is an extremely rare condition; hence, a definitive investigation that will confirm the diagnosis and exclude other conditions will be helpful to reassure patients as to the benign nature of this illness.)

Further investigations are not required but may have been carried out as part of a general evaluation of jaundice or before the diagnosis of DJS is made:

An ultrasound scan of the liver and biliary tree is typically normal; oral cholecystography fails to visualize the gallbladder even when carried out with supplemental doses of contrast.

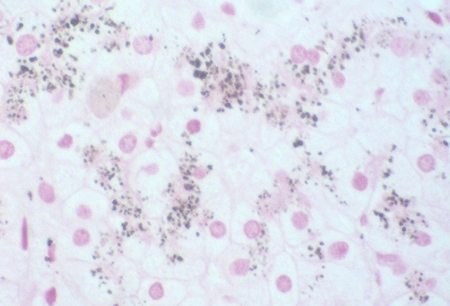

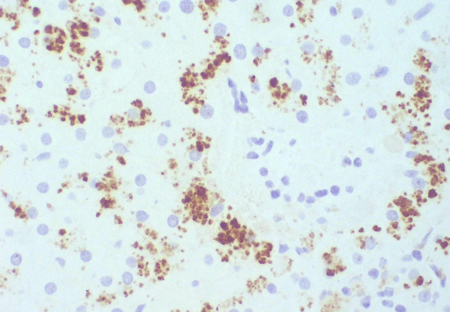

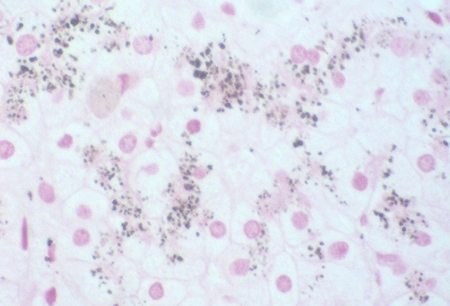

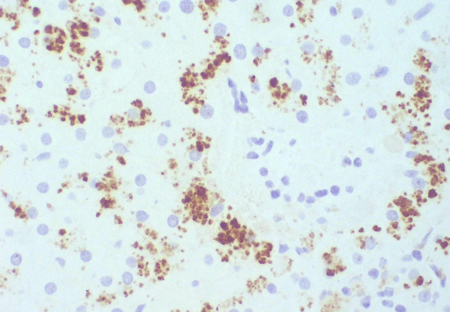

Dark liver noted during surgery may prompt a liver biopsy to exclude more serious pathology. Normal liver histology and the characteristic parenchymal deposition of a melanin-like pigment would help to establish a diagnosis of DJS. This can be demonstrated with Masson-Fontana stain or immunohistochemistry. This striking pigmentation of liver cells is lacking in all other hepatic diseases including Rotor syndrome.[3]Dubin IN. Chronic idiopathic jaundice: a review of 50 cases. Am J Med. 1958 Feb;24(2):268-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13508683?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Masson-Fontana stain showing the pigment in a patient with DJSPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in patient showing the pigment, but no canalicular structuresPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends].

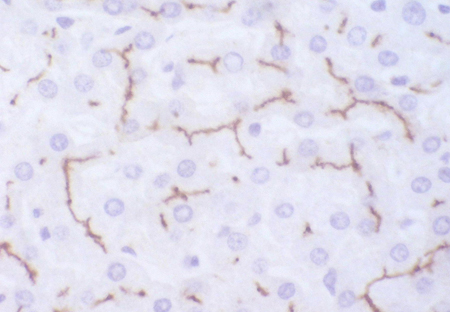

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in patient showing the pigment, but no canalicular structuresPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in a control, showing no pigment, but irregularly branching canalicular structures can be seenPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends].

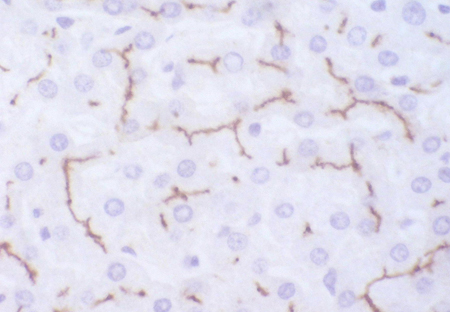

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in a control, showing no pigment, but irregularly branching canalicular structures can be seenPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends].

Gene sequencing

Mutational analysis of the ABCC2 gene (encoding MRP2), using next generation sequencing and Sanger sequencing, has been reported as a potential diagnostic tool.[31]Al-Hussaini A, AlSaleem B, AlHomaidani H, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and molecular characterization of neonatal-onset Dubin-Johnson syndrome in a large case series from the Arabs. Front Pediatr. 2021 Nov;9:741835.

https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.741835

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34858902?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Lyu Y, Wei X, Xu J, et al. [Diagnosis of a patient with Dubin-Johnson syndrome by using next generation sequencing]. [in chi]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2019 Mar 10;36(3):242-245.[37]Wu L, Zhang W, Jia S, et al. Mutation analysis of the ABCC2 gene in Chinese patients with Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Exp Ther Med. 2018 Sep 3;16(5):4201-4206.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6176208

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30344695?tool=bestpractice.com

If there are existing genetic test results, do not perform repeat testing unless there is uncertainty about the existing result, e.g., the result is inconsistent with the patient’s clinical presentation or the test methodology has changed.[38]American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2021 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230326143738/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-college-of-medical-genetics-and-genomics

Emerging tests

Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) also transports leukotrienes into the bile. When defective, as in DJS, there is increased urinary excretion of leukotriene metabolites. This may become a useful diagnostic test, but is not yet in widespread clinical use.[39]Mayatepek E, Lehmann WD. Defective hepatobilary leukotriene elimination in patients with Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 1996 May 30;249(1-2):37-46.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8737590?tool=bestpractice.com

Some studies have reported that severe deleterious mutations involving the ATP-binding cassettes of the MRP2 protein were more common in patients with neonatal-onset DJS, whereas variants involving other domains of the MRP2 protein were more common in the adult patients.[31]Al-Hussaini A, AlSaleem B, AlHomaidani H, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and molecular characterization of neonatal-onset Dubin-Johnson syndrome in a large case series from the Arabs. Front Pediatr. 2021 Nov;9:741835.

https://www.doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.741835

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34858902?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Togawa T, Mizuochi T, Sugiura T, et al. Clinical, pathologic, and genetic features of neonatal Dubin-Johnson Syndrome: a multicenter study in Japan. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:161-167.e1.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29499989?tool=bestpractice.com

[41]Lee JH, Chen HL, Chen HL, et al. Neonatal Dubin-Johnson syndrome: long-term follow-up and MRP2 mutations study. Pediatr Res. 2006 Apr;59(4 pt 1):584-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1203/01.pdr.0000203093.10908.bb

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16549534?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in patient showing the pigment, but no canalicular structuresPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in patient showing the pigment, but no canalicular structuresPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in a control, showing no pigment, but irregularly branching canalicular structures can be seenPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunohistochemistry for canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter in a control, showing no pigment, but irregularly branching canalicular structures can be seenPersonal collection of Professor Bernard Portmann, King's College Hospital, London, with permission [Citation ends].