Recommendations

Key Recommendations

If you suspect cardiac tamponade (i.e., the patient has a raised jugular venous pressure, tachycardia, heart failure, or pulsus paradoxus) get help immediately from a senior colleague. Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening complication of pericarditis and these patients require urgent pericardiocentesis.[1] See Cardiac tamponade.

Organise hospital admission for any patient with acute pericarditis and a suspected underlying aetiology requiring inpatient management or at least one high-risk feature. See Triage of patients with acute pericarditis below.

Start a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and colchicine as first-line medical therapy to help relieve symptoms, as long as there are no contraindications.[1]

Further management depends on whether the pericarditis is purulent or non-purulent, and whether it is a first presentation or recurrent.[1] Interventions may include corticosteroids, pericardiectomy, immunosuppressants, and treatment of any underlying cause.[1]

Organise admission to hospital for any patient with:

A clinical presentation that suggests an underlying aetiology requiring inpatient management[1]

Any of the following high-risk features:[1]

Major risk factors (associated with poor prognosis after multivariate analysis):

High fever (i.e., >38°C [>100.4°F])

Subacute course (i.e., symptoms over several days without a clear-cut acute onset)

Evidence of a large pericardial effusion (i.e., diastolic echo-free space >20 mm)

Cardiac tamponade

Failure to respond within 7 days to a NSAID

Minor risk factors (based on expert opinion and literature review):

Pericarditis associated with myocarditis (myopericarditis; associated with a rise in troponin)

Immunosuppression

Trauma

Oral anticoagulant therapy.

Ensure a patient with any of these high-risk features has investigation of the underlying cause, as well as careful observation and follow-up.[1]

Otherwise, if the patient does not have any high-risk features or a clinical presentation that suggests an underlying aetiology requiring inpatient management, consider outpatient management. Start treatment (i.e., empirical anti-inflammatories) and arrange follow-up after 1 week to assess the response to treatment.[1]

If you suspect cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication of pericarditis, get help immediately from a senior colleague; these patients require urgent pericardiocentesis.[1] See Cardiac tamponade.

Other indications for pericardiocentesis include suspected purulent pericarditis, high suspicion of neoplastic pericarditis, or a large or symptomatic pericardial effusion in a patient with non-purulent pericarditis.[1]

Although very rare in the antibiotic era, purulent pericarditis is life-threatening and requires a high index of suspicion. Seek early input from a senior or specialist colleague.[44]

The patient will need further treatment based on whether the pericarditis is purulent or non-purulent.[1] See Purulent disease and Non-purulent disease: first presentation below.

Initial drug treatment

Start a NSAID (as long as there are no contraindications) immediately after diagnosis for symptom management.[1]

To guide treatment duration, evaluate the patient’s symptoms and their C-reactive protein levels. In general, for a patient with uncomplicated pericarditis, continue the NSAID at the initial dose for 1 to 2 weeks before tapering gradually.[1]

Practical tip

A common error is to taper the NSAID too quickly, which can result in recurrence of symptoms.

Choice of drug is based on patient characteristics (e.g., contraindications, previous efficacy, or adverse effects), presence of concomitant diseases (e.g., favour aspirin over other NSAIDs if antiplatelet therapy is required), and physician expertise.[1][18]

Practical tip

Aspirin is preferred for patients developing pericarditis following a myocardial infarction, as other NSAIDs adversely affect myocardial healing and are associated with increased risk of future cardiac events.[58] If high-dose aspirin is not effective, consider paracetamol or an opioid analgesic.

NSAIDs reduce fever, chest pain, and inflammation but do not prevent tamponade, constriction, or recurrent pericarditis.

Add a proton-pump inhibitor to reduce gastrointestinal adverse effects.[1][11][12][13]

Add colchicine, unless the patient has tuberculosis pericarditis.[1][20][59][60][61] See Underlying cause below. Continue colchicine for 3 months.[1][20][59][60]

Colchicine is crucial to prevent recurrent pericarditis, improve response, and increase remission rates.[1]

Only consider using a low-dose corticosteroid with specialist guidance from a rheumatologist and a cardiologist.

A corticosteroid is an appropriate option for a small proportion of patients, specifically if:

Do not use corticosteroids in a patient with viral pericarditis because of the risk of re-activation of the viral infection and ongoing inflammation.

Use corticosteroids at low to moderate doses.[18] Continue with the initial dose until symptoms have resolved and the patient’s C-reactive protein level has normalised. Once this is achieved, taper the dose gradually.[1]

Exercise restriction

Advise the patient to restrict strenuous physical activities:[1][64]

Non-athletes: until symptoms have resolved and C-reactive protein has normalised, while also taking into account the patient’s previous history and other clinical conditions[1]

Athletes: for a minimum of 3 months until symptoms have resolved and C-reactive protein, ECG, and echocardiography have normalised.[1]

Purulent pericarditis is life-threatening; it requires a high index of suspicion and needs aggressive treatment. Seek early input from a specialist or senior colleague.[1]

Bear in mind that purulent pericarditis is very rare in the antibiotic era.[44]

Suspect purulent pericarditis if the patient is unwell with signs of sepsis and all other causes have been excluded.[1] See Sepsis in adults.

Antibiotics

Start empirical intravenous antibiotics as soon as you suspect purulent pericarditis. Use an anti-staphylococcal antibiotic plus an aminoglycoside.[1] Seek advice from a microbiologist.

Tailor the antibiotics once the underlying pathogens are identified from pericardial fluid and blood cultures.[1]

Continue intravenous antibiotics until fever and clinical signs of infection, including leukocytosis, have resolved.[3]

Specialist management

Specialist management may include pericardiocentesis or surgical pericardial intervention.[1]

Treat the underlying cause if known. Pericarditis can be caused by:

Viral infections (e.g., coxsackievirus A9 or B1-4, echovirus, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella, rubella, HIV, parvovirus-19, SARS-CoV-2)

Tuberculosis (a common cause in the developing world)

Secondary immune processes (e.g., rheumatic fever, post-cardiotomy syndrome, post-myocardial infarction syndrome)

Metabolic disorders (e.g., uraemia, myxoedema)

Radiotherapy

Cardiac surgery

Percutaneous cardiac interventions

Systemic autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, reactive arthritis, familial Mediterranean fever, systemic vasculitides, inflammatory bowel disease)

Bacterial/fungal/parasitic infections

Trauma

Certain drugs (e.g., hydralazine, antineoplastic drugs, clozapine, tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, phenytoin)[1]

Neoplasms.

Seek specialist advice as needed.

If the patient has tuberculous pericarditis, first-line treatment is 4 to 6 weeks of antituberculous therapy.[1][3][16][39][65] See Extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

When tuberculous pericarditis is confirmed in an non-endemic area, a suitable 6-month regimen is effective; empirical therapy is not required in the absence of an established diagnosis in non-endemic areas.[1]

Adjunctive therapy with corticosteroids and immunotherapy has not been shown to be beneficial.[66][67] However, corticosteroids may be considered in a patient with tuberculous pericarditis who is HIV-negative.[68] [

]

]

Pericardiectomy is recommended if the patient does not improve or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy.[1]

Most patients with uraemic pericarditis respond to intensive dialysis within 1 to 2 weeks.

Autoimmune disorders are treated with corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive therapies depending on the specific condition.

Treatment of neoplasms may involve any combination of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery, depending on the type of tumour identified.[1][39][40]

Drug treatment

If the patient has recurrent pericarditis, give an NSAID. Add colchicine, unless the patient has tuberculosis pericarditis.[1]

Continue colchicine for 6 months to prevent recurrence.[1] If indicated, consider a longer duration of treatment with colchicine according to the patient’s clinical response.[1] Colchicine is crucial to reduce recurrences, improve response, and increase remission rates.[1]

Continue the NSAID until symptoms resolve and C-reactive protein (CRP) has settled. Taper drug therapy gradually according to the patient’s symptoms and their CRP level.[1]

If the patient does not respond completely to an NSAID plus colchicine, revisit the diagnosis of pericarditis and ensure other causes are ruled out. If there is ongoing inflammation on computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging, seek advice from a rheumatologist to consider adding a corticosteroid at a low to moderate dose.[1]

Avoid corticosteroids if infections, particularly bacterial infections and tuberculosis, cannot be excluded.[1]

In general, restrict corticosteroid use to patients with specific indications (including systemic inflammatory diseases, post-cardiotomy syndromes, and pregnancy), contraindications, or intolerance to the use of NSAIDs (e.g., hypersensitivity, recent peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding, oral anticoagulant therapy when the bleeding risk is considered high or unacceptable), or persistent disease despite appropriate doses.[1]

Alternative therapies for recurrent pericarditis are immunosuppressants – including intravenous immunoglobulin, interleukin-1 inhibitors (e.g., anakinra), and azathioprine – but these should only be started by a rheumatologist.[1][20][59][69][70][71][72][73][74][75]

Exercise restriction

Advise the patient to restrict strenuous physical activities:[1][64]

Non-athletes: until symptoms have resolved and CRP has normalised, while also taking into account the patient’s previous history and other clinical conditions[1]

Athletes: for a minimum of 3 months until symptoms have resolved and CRP, ECG, and echocardiography have normalised.[1]

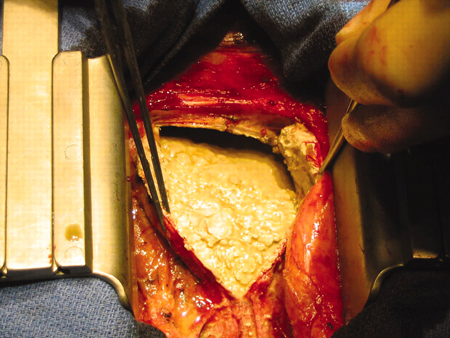

Pericardiectomy

Pericardiectomy can be considered if the patient has persistent symptomatic recurrent pericarditis (particularly where constriction is present, e.g., following cardiac surgery or radiotherapy), but is a significant and invasive procedure which should be carried out only after careful consideration by the multidisciplinary team including a full evaluation of risks and benefits.[1][53][76] Operative mortality is high.[77]

Pericardiectomy is also indicated if a patient has tuberculous pericarditis with recurrent effusions or evidence of constrictive physiology despite medical therapy.[3] See Extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Pericardiectomy is particularly recommended if the patient’s condition is not improving or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy.

Standard antituberculosis drugs for 6 months are recommended for the prevention of tuberculous pericardial constriction.[1]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pericardiectomy in a 56-year-old male patient with idiopathic calcific constrictive pericarditis. The pericardium is thickened and calcifiedPatanwala I, Crilley J, Trewby PN. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0015 [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer