Aetiology

Acute pericarditis can be idiopathic or due to an underlying systemic condition (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus). As many as 90% of cases are either idiopathic or due to viral infections (e.g., coxsackievirus A9 or B1-4, echovirus, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella, rubella, HIV, parvovirus-19, SARS-CoV-2).[2][3][5][13][19][20] Onset is frequently post-viral, with no evidence of virus present in the pericardium. Systemic autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, reactive arthritis, familial Mediterranean fever, systemic vasculitides, inflammatory bowel disease) are also a common cause.[21][22] However, there are numerous other less common causes, including bacterial/fungal/parasitic infections, secondary immune processes (e.g., rheumatic fever, post-cardiotomy syndrome, post-myocardial infarction syndrome), pericarditis and pericardial effusions in diseases of surrounding organs (e.g., acute myocardial infarction, myocarditis, paraneoplastic syndromes), metabolic disorders (e.g., uraemia, myxoedema), trauma, neoplasms, and certain drugs (e.g., hydralazine, antineoplastic drugs, clozapine, tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, phenytoin).[1] Rarely, pericarditis occurs after vaccination (including influenza and mRNA COVID-19 vaccination).[23][24][25][26] Fungal and drug causes are rare.

In developed countries, other causes include radiotherapy, cardiac surgery, percutaneous cardiac interventions, and HIV. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a common cause in developing countries.[12][14] Pericarditis commonly occurs 1 to 3 days after a myocardial infarction (MI). It can also occur weeks or months later (Dressler's syndrome).[13] Post-cardiac injury syndrome is a broad term that describes pericarditis with or without effusion that results from an MI or iatrogenic injury to the pericardium. It includes post-MI syndrome (Dressler's), post-cardiotomy syndrome, and post-traumatic pericarditis (due to percutaneous coronary intervention or implantable electronic device placement, i.e., pacemaker or defibrillator).[18][27]

Pathophysiology

The pericardium consists of a 2-layered pliable, fibroserous sac that covers the surface of the heart. The inner layer, the visceral pericardium, is adherent to the myocardium. It has a microvillous surface that secretes pericardial fluid. The outer layer, or parietal pericardium, is contiguous with the inner layer. It is composed of collagen layers with interspersed elastin fibrils. Both layers are normally only 1 to 2 mm thick and a space containing 15 to 35 mL of pericardial fluid separates them. The pericardium is perfused by the internal mammary arteries and innervated by the phrenic nerve. The pericardium protects and restrains the heart. In addition, it determines cardiac filling patterns, limits chamber dilatation, and equilibrates compliance between the 2 ventricles.

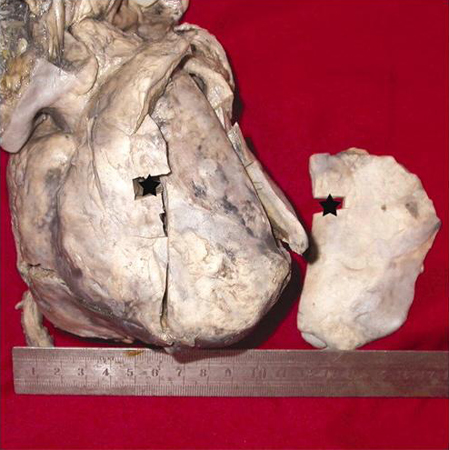

Signs and symptoms of acute pericarditis result from inflammation of the pericardial tissue. The pericardium is well-innervated and inflammation causes severe pain. Pericarditis can be either fibrinous (dry) or effusive with a purulent, serous, or haemorrhagic exudate. The formation of a concomitant effusion is usually due to a response to the inflammation. The normal pericardium is permeable to water and electrolytes and pericardial fluid is in dynamic equilibrium with the blood serum. Inflamed pericardial tissue impairs this equilibrium. Local production of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, tumour necrosis factor, and interleukins can cause weeping of fluid from the visceral pericardium, as well as exudation of larger molecules that attract additional fluid and impair resorption.[12][13][28] Constrictive pericarditis impedes normal diastolic filling and can be a medium to late complication of acute pericarditis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Constrictive pericarditis identified at autopsy; the right section is scar tissue cut from the very front of the heartXu JD, Cao XX, Liu XP, et al. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.03.2009.1688 [Citation ends].

Classification

Clinical classification[1]

Pericarditis can be classified by duration of inflammation as well as by aetiology and complications/sequelae.

A. Acute pericarditis (new onset, <4-6 weeks)

Inflammatory pericardial syndrome associated with at least 2 of the following 4 criteria:

Characteristic chest pain: typically sharp, pleuritic; relieved by sitting forwards and worsened by lying flat

Pericardial friction rub; 'like walking through crunchy snow'

New widespread diffuse concave upwards ST elevation (saddle-shaped) or PR depression on ECG

New or worsening pericardial effusion.

Additional supporting findings include:

Elevated inflammatory markers (i.e., C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count)

Evidence of pericardial thickening/inflammation by advanced imaging techniques (i.e., cardiac computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging).

Can be associated with a pericardial effusion that is fibrinous or effusive (serous or serosanguinous).

B. Incessant pericarditis

Signs and symptoms lasting >4 to 6 weeks but <3 months without remission.

C. Recurrent pericarditis

Recurrence of signs and symptoms after an initial documented episode of acute pericarditis with an intervening symptom-free interval of ≥4 to 6 weeks.

D. Chronic pericarditis

Signs and symptoms persisting for >3 months.

Subtypes:

Constrictive (due to chronically thickened pericardium)

Effusive-constrictive (combination of tense effusion in the pericardial space and constriction by the thickened pericardium)

Adhesive (non-constrictive).

Aetiological classification[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

A. Infectious

Viral

Coxsackievirus A9 or B1-4

Echovirus

Mumps

Epstein-Barr virus

Cytomegalovirus

Varicella

Rubella

HIV

Parvovirus-19

Dengue

Zika

SARS-CoV-2

Bacterial

Pneumococcal

Meningococcal

Gonocococcal

Haemophilus

Chlamydial

Tuberculous

Treponema

Borreliosis

Propionibacteria

Fungal

Candida

Histoplasma

Parasitic

Entamoeba histolytica

Echinococcus

B. Associated with systemic autoimmune disorders

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatoid arthritis

Systemic sclerosis

Reactive arthritis

Familial Mediterranean fever

Systemic vasculitides

Inflammatory bowel disease

Sarcoidosis

C. Secondary immune process

Rheumatic fever

Post-cardiotomy syndrome

Post-myocardial infarction (MI) syndrome

Post-cardiac ablation or percutaneous coronary intervention

D. Pericarditis and pericardial effusions in diseases of surrounding organs

Acute MI

Myocarditis

Paraneoplastic syndrome

E. Associated with metabolic disorders

Uraemia

Myxoedema

F. Traumatic

Direct injury

Penetrating thoracic injury

Oesophageal perforations

Indirect injury

Non-penetrating thoracic injury

Mediastinal radiation

G. Neoplastic

Primary tumours (rare)

Mesothelioma

Angiosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma

Secondary metastases

Lung carcinoma

Breast carcinoma

Leukaemia and lymphoma

Gastric and colon

Melanoma

Others, including carcinoid

Pericarditis in cancer patients is often non-malignant (e.g., secondary to mediastinal radiation or opportunistic infection)

H. Drug-related

Lupus-like syndrome

Procainamide

Hydralazine

Methyldopa

Isoniazid

Phenytoin

Chemotherapeutic agents (usually with associated cardiomyopathy)

Doxorubicin

Daunorubicin

Cyclophosphamide

Fluorouracil

Cytarabine

Hypersensitivity reaction with eosinophilia

Penicillins

Other

Amiodarone

Thiazides

Sulfa drugs

Ciclosporin

Tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., CTLA-4 inhibitors, PD-1 inhibitors, and PD-L1 inhibitors)

I. Idiopathic

Idiopathic and viral causes are the most common. Autoimmune disorders are also a common cause. Drugs are a rare cause, and fungi are a very rare cause.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer