Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Symptoms vary depending on the speed of accumulation of pericardial effusion. Suspect cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication of pericarditis, early if the patient is hypotensive and has a raised jugular venous pressure, tachycardia, cool extremities, heart failure, or pulsus paradoxus.[1] Get help immediately from a senior colleague; these patients require urgent echocardiography and consideration for pericardiocentesis.[1] See Cardiac tamponade.

The classic triad of distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds, and hypotension (Beck’s triad) may not be present.[35]

Be aware that acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis; confirm the diagnosis if at least 2 of the 4 following clinical criteria are present:[1][16][20][38][39][40]

Characteristic chest pain; typically sharp, pleuritic, and relieved by sitting forwards

Pericardial friction rub

New widespread concave upwards ST elevation or PR depression on ECG

Pericardial effusion (new or worsening).

Order key initial investigations including ECG, blood tests (e.g., troponin, creatine kinase, and inflammatory markers [white blood cell count and C-reactive protein ± erythrocyte sedimentation rate]), and echocardiography. Be aware that investigation of the underlying cause is not necessary unless the patient has a ‘high-risk’ feature. See the Investigations section for more information.

In practice, a patient who is young, fit, and well can be discharged before having an echocardiography; this should be organised as an early outpatient investigation.

Be aware that acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis; confirm the diagnosis if at least 2 of the 4 following clinical criteria are present:[1][16][20][38][39][40]

Characteristic chest pain; typically sharp, pleuritic, and relieved by sitting forwards

Pericardial friction rub

New widespread diffuse concave upwards ST elevation and/or PR depression on ECG

Pericardial effusion (new or worsening).

The key symptom is acute onset of chest pain.[1]

Typically sharp, and pleuritic.[1] The pain may also be stabbing or aching.

Almost all patients report relief of pain with sitting up or leaning forward.[1]

Usually central but may radiate to one or both trapezius ridges (phrenic nerves both innervate the pericardium and trapezius ridges), the neck, the arms, or the left shoulder.[16]

Can mimic the pain of myocardial ischaemia or infarction (particularly when dull or pressure-like), pulmonary embolism, or aortic dissection. See the Differentials section for more information.

In practice, dull or pressure-like pain is commonly associated with myocardial involvement (myopericarditis or perimyocarditis).

Trapezius ridge pain is more specific for pericardial pain than pain due to myocardial infarction.[16]

Generally constant, not related to exertion, and poorly responsive to nitrates.[12][14]

Practical tip

It is crucial to rule out pulmonary embolism as a differential. If a patient with pericarditis is given anticoagulation (i.e., treatment-dose low molecular weight heparin), they can develop life-threatening cardiac tamponade due to bleeding into the pericardial space.[41] See Pulmonary embolism.

Practical tip

Chest pain caused by myocardial ischaemia/infarction (rather than pericarditis) typically:

Is described as pressure-like, heavy, and squeezing, rather than sharp and pleuritic

Does not with vary with respiration or positional changes

Is not associated with a pericardial friction rub (unless there is associated pericarditis)[11][28][42]

Lasts minutes to hours, rather than hours to days

Is associated with other key features such as nausea and vomiting, marked sweating, or breathlessness (or particularly a combination of these), or risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[43]

Suspect purulent pericarditis if the patient is unwell with signs of sepsis and all other causes have been excluded; see Sepsis in adults.[1]

Although very rare in the antibiotic era, purulent pericarditis is life-threatening and requires a high index of suspicion. Seek early input from a specialist or a senior colleague.[44]

Include in your history an assessment of the following risk factors for pericarditis:[1][2][3]

Male sex

Age 20 to 50 years

Transmural myocardial infarction

Cardiac surgery

Neoplasm

Viral and bacterial infection (e.g., coxsackievirus A9 or B1-4, echovirus, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella, rubella, HIV, parvovirus-19, SARS-CoV-2, tuberculosis); or rarely, after vaccination (including influenza and mRNA COVID-19 vaccination).[23][24][25][26]

The patient may present with a recent history of an upper respiratory tract infection or diarrhoeal illness[15]

Uraemia

Dialysis treatment

Systemic autoimmune disorders.

Suspect cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication of pericarditis, early if the patient has cold peripheries, hypotension, raised jugular venous pressure, tachycardia, heart failure, or pulsus paradoxus.[1] Get help immediately from a senior colleague; these patients require urgent pericardiocentesis.[1] See Cardiac tamponade.

The classic triad of distended neck veins, muffled heart sounds, and hypotension (Beck’s triad) may not be present.[35]

Cardiac tamponade associated with pericarditis can have an insidious onset with non-specific symptoms and signs.

Examine the patient for:

Pericardial friction rub

This is a key finding that supports the diagnosis.[1] The presence of a rub is highly specific, but it is often absent at initial presentation and its absence does not rule out the diagnosis (rub may be present in less than 33% of cases).[1]

It is a superficial scratchy or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the left sternal border and at the cardiac borders.[1]

Always examine a patient with suspected pericarditis repeatedly because the rub can come and go over several hours.[13] Sensitivity of a rub is based on the frequency of cardiac auscultation.

Signs of the underlying cause

For example, there may be signs of systemic infection, or signs of underlying disease such as systemic inflammatory disease or cancer.[1]

Features of bacterial pericarditis include high fever, tachycardia, and cough. Patients with postoperative bacterial pericarditis may have signs of sternal wound infection or mediastinitis.

Complications such as pericardial effusion and constrictive pericarditis. See Pericardial effusion.

Practical tip

A pericardial friction rub can be distinguished from a pleural rub by asking the patient to hold their breath - a pericardial friction rub will still be heard when the patient holds their breath, and occurs with every heartbeat. A pericardial rub is heard maximally during expiration and can sound like the ‘crunch’ heard when walking over fresh snow.

Bear in mind that a pericardial rub may be absent if a large pericardial effusion is present because the inflamed pericardium will be separated and unable to rub together.

Although the diagnosis is clinical, some investigations are indicated.[1][3][12][14][40] Bear in mind that the yield of diagnostic tests to look for the underlying cause is relatively low.

Organise admission and investigate the underlying cause if the patient has any of the following high-risk features:[1]

Major risk factors (associated with poor prognosis after multivariate analysis):

High fever (i.e., >38°C [>100.4°F])

Subacute course (i.e., symptoms over several days without a clear-cut acute onset)

Evidence of a large pericardial effusion (i.e., diastolic echo-free space >20 mm)

Cardiac tamponade

Failure to respond within 7 days to a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

Minor risk factors (based on expert opinion and literature review):

Pericarditis associated with myocarditis (myopericarditis; associated with a rise in troponin)

Immunosuppression

Trauma

Oral anticoagulant therapy.

It is not always essential to admit the patient and determine the underlying cause.[1] Acute pericarditis tends to follow a benign course, particularly when precipitated by a common cause in countries with a low prevalence of tuberculosis. Patients without high-risk features can be managed as outpatients (with short-term follow-up within 1 week).[1]

Initial investigations

ECG

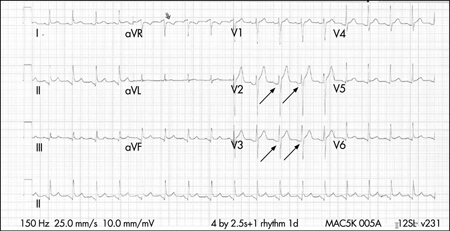

Perform an ECG in any patient with suspected acute pericarditis.[1]

Typical ECG changes occur in up to 60% of patients.[1]

The classic ECG changes are:

Global upwardly concave (saddle-shaped) ST-segment (J-point) elevation with PR-segment depression in most leads[45]

J-point depression and PR elevation in leads aVR and V1.

If the patient is seen soon after symptom onset, PR depressions may be noted prior to ST elevation.

The ECG may evolve over 4 phases: stage 1 consists of ST elevation and upright T waves that may resolve to normal (stage 2) over a period of several days or evolve further to T-wave inversion (stage 3) and then to normal (stage 4).

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG in a patient with acute pericarditis, showing diffuse ST-segment elevation in the precordial leads. There is also PR-segment depression in leads V2-V6 (arrows)Rathore S, Dodds PA. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.097071 [Citation ends].

Be aware of the ECG signs of cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication of pericarditis. These include:

Low voltage, electrical alternans

Electromechanical dissociation (associated with end-stage tamponade).

Blood tests

Always order:

Full blood count

Urea and electrolytes

Elevated levels (particularly >21.4 mmol/L [>60 mg/dL]) suggest a uraemic cause[14]

Liver function tests

Liver congestion may be present if the patient is developing cardiac tamponade[46]

C-reactive protein (CRP)

Troponin

Serial troponin measurement may be necessary in some patients.[47] However, a patient may not require this if the initial troponin is negative and diagnosis of pericarditis is clear.[47]

Elevated levels may be present in 35% to 50% of patients with pericarditis and reflect myocardial involvement (myopericarditis).[11] However, the test is not specific or sensitive.[11][14]

The magnitude of elevation correlates with the extent of ST-segment elevation and can be in the range considered diagnostic of acute myocardial infarction in some patients. Elevated levels do not appear to confer prognostic significance.

Levels return to normal within 1 to 2 weeks of acute presentation (often within days).

Consider also requesting:

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

Creatine kinase (CK)

Elevated CK indicates myocardial injury[1]

Autoimmune screen

If you suspect an autoimmune cause of pericarditis

Viral screen (including HIV)

If you suspect a viral cause of pericarditis

Blood cultures

If you suspect purulent pericarditis.

Practical tip

You must order a D-dimer to rule out pulmonary embolism if this is suspected as a differential. This is crucial because if a patient with pericarditis is given anticoagulation (i.e., treatment-dose low molecular weight heparin), they can develop life-threatening cardiac tamponade.[41]

However, be aware that D-dimer may also be raised in a patient with pericarditis; seek advice from a senior colleague if you are unsure.[48] If the diagnosis is uncertain, further investigation (e.g., with computed tomographic pulmonary angiography) may be required.

See Pulmonary embolism.

Pericardiocentesis

If you suspect cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication of pericarditis, get help immediately from a senior colleague; these patients require urgent pericardiocentesis.[1]

Other indications for pericardiocentesis include suspected purulent pericarditis, high suspicion of neoplastic pericarditis, or a large or symptomatic pericardial effusion in a patient with non-purulent pericarditis.[1]

Send pericardial fluid for analysis, which should include testing for bacterial, fungal, autoimmune, and tuberculous causes, and protein content and microscopy/cytology:[1]

Tuberculous pericarditis: diagnostic accuracy can be improved with identification of the organism from pericardial fluid.[49][50] Adenosine deaminase activity within the pericardial effusion may also aid in the diagnosis as an adjunctive marker[1][51]

Viral pericarditis: consider a comprehensive work-up of histological, cytological, immunohistological, and molecular investigations in pericardial fluid for definitive diagnosis[1]

Neoplastic pericarditis: obtain cytological analysis of pericardial fluid to confirm malignant pericardial disease.[1]

Chest x-ray

Order a chest x-ray for any patient with suspected acute pericarditis.[1]

Chest x-ray is often normal unless there is an associated large pericardial effusion (>300 mL), in which case the cardiothoracic ratio will be increased.[1]

Classic flask-shaped heart in large pericardial effusion.

The chest x-ray may also demonstrate pleuropericardial disease, signs of heart failure (if there is an indolent onset), concomitant lung pathology providing evidence of tuberculosis, fungal disease, pneumonia, or a neoplasm that may be related to the disease.

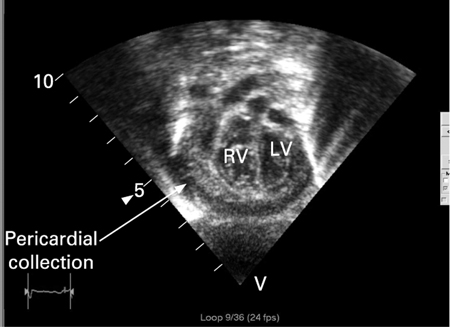

Echocardiography

Organise transthoracic echocardiography for any patient with suspected pericarditis.[1] If you suspect cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening complication of pericarditis, this should be performed urgently at the bedside.[1]

The European Society of Cardiology recommends echocardiography for all patients in order to complete a full risk stratification prior to discharge.[1] However, in practice, a patient who is young, fit, and well can be discharged before having an echocardiography; this should be organised as an early outpatient investigation.

Echocardiography is important in detecting pericardial effusions, which are found in up to 60% of cases and are generally small in size.[1][52] Presence of a pericardial effusion is consistent with acute pericarditis and is one of the criteria for its diagnosis.[1]

Echocardiography can also help differentiate pericarditis from acute coronary syndromes. Global ST elevations in the absence of left ventricular wall motion abnormalities and a trivial pericardial effusion support the diagnosis of acute pericarditis. However, around 5% of patients with acute pericarditis and myocardial involvement may demonstrate wall motion abnormalities.[1]

Echocardiography is insensitive to pericardial inflammation in dry pericarditis; computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should be used to detect pericardial inflammation (see below).[52]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiogram in a baby with purulent pericarditis, showing a pericardial collection. LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricleKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

Further investigations

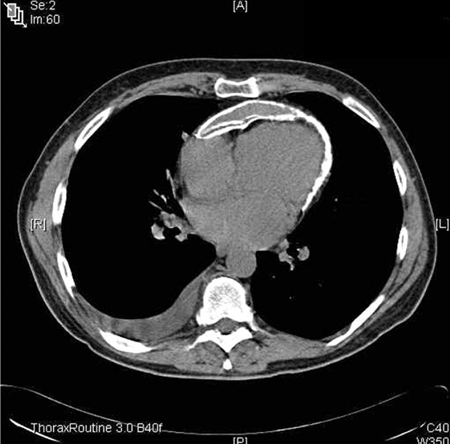

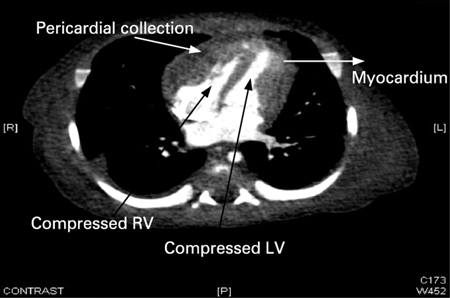

Chest computed tomography (CT)/cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Consider additional imaging with CT or MRI if the clinical presentation suggests complicated pericarditis or the presentation is atypical.[18][52][53]

The key finding in acute pericarditis is pericardial thickening.[18] Pericardial enhancement may be seen on cardiac magnetic resonance late gadolinium enhancement imaging.[54]

CT/MRI may also detect complications such as pericardial effusion or constrictive pericarditis, especially when the echocardiographic findings are inconclusive.[1] MRI is more sensitive for constrictive pericarditis.[18]

Additional diagnostic information may also be obtained when there is associated chest trauma, particularly when penetrating; or in the setting of acute myocardial infarction, carcinoma, pulmonary or thoracic infection, or pancreatitis.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT showing a double layer of pericardial calcification in a 56-year-old male patient with idiopathic calcific constrictive pericarditisPatanwala I, Crilley J, Trewby PN. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0015 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT in a baby with purulent pericarditis, showing a pericardial collection with compression of the left (LV) and right (RV) ventriclesKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT in a baby with purulent pericarditis, showing a pericardial collection with compression of the left (LV) and right (RV) ventriclesKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer