Approach

Typically, patients are asymptomatic and HTG is detected on routine blood testing.[5] Clinical suspicion for HTG should be raised in patients with unexplained atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or acute pancreatitis. A lipid profile should also be obtained in patients with any of the known precipitating factors.

History

A family history of hyperlipidaemia or diabetes should be sought. Historical features may include symptoms of ASCVD (angina, claudication), recurrent abdominal pain, or known secondary causes of HTG. Secondary causes of HTG include medical conditions, lifestyle factors, and drugs:[4][5][9]

Medical conditions: diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, obesity, partial or generalised lipodystrophy, chronic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, pregnancy (particularly in the third trimester when triglyceride [TG] elevation associated with pregnancy is peaking), myeloma, systemic lupus erythematosus, liver disease, HIV infection, Cushing syndrome, sarcoidosis

Lifestyle factors: excessive alcohol consumption; diet high in saturated fat, sugar, or high glycaemic index foods; sedentary lifestyle

Drugs: glucocorticoids, anabolic steroids, oral oestrogens, thiazide and loop diuretics, non-cardioselective beta-blockers, isotretinoin, bexarotene, propofol, bile acid sequestrants, cyclophosphamide, asparaginase, capecitabine, interferon, tacrolimus, sirolimus, ciclosporin, protease inhibitors, second-generation antipsychotic agents (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine).

Symptoms and signs

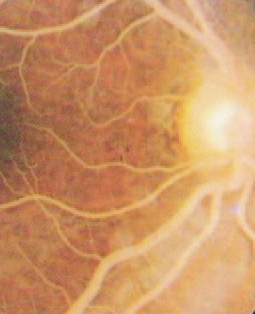

The presence of symptoms and signs of HTG is related to the degree of TG elevation. There are no symptoms or physical findings in patients with mild-to-moderate HTG. Patients with severe HTG and chylomicronaemia develop characteristic features, which include eruptive xanthomas (raised crops of small yellowish papules encircled by erythematous halos that appear on extensor surfaces of the extremities, the buttocks, and the shoulders) and lipaemia retinalis (whitish-pink appearance of retinal vessels and retinal pallor with pinkish hue detected on fundoscopic examination).[20][52] Other characteristic symptoms and signs of chylomicronaemia include hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting. Much less common clinical features (<10% of patients) include intestinal bleeding, pallor, anaemia, irritability, diarrhoea, seizures, and encephalopathy.[14] Infants with familial chylomicronaemia syndrome can present with failure to thrive and abdominal pain.[14]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Eruptive xanthomasFrom the personal collection of Professor Hegele; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lipaemia retinalis. Pinkish-white discolouration of retinal blood vessels on ophthalmoscopyFrom the personal collection of Professor Hegele, used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lipaemia retinalis. Pinkish-white discolouration of retinal blood vessels on ophthalmoscopyFrom the personal collection of Professor Hegele, used with permission [Citation ends].

Initial laboratory testing

TG level is obtained as part of a routine lipid panel that also includes total and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, along with a calculated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and calculated non-HDL-cholesterol. Non-HDL-cholesterol is a derived measurement that is stable irrespective of fasting status. Calculated LDL-cholesterol is not accurate if TG >4.6 mmol/L (>400 mg/dL). A 12- to 14-hour period of fasting is recommended to obtain optimal values of TG. Non-fasting TG has been proposed to be more convenient to measure and has been strongly associated with atherosclerosis risk.[53] However, if non-fasting TG is so high that LDL-cholesterol cannot be calculated, a repeat fasting lipid profile is recommended. Acute illnesses and physiological stress can transiently raise TG levels; values should be confirmed on repeat testing, especially if diagnosis is made during an acute illness.

In the US, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines define moderate HTG as fasting or non-fasting TG 2.0 to 5.6 mmol/L (175-499 mg/dL) and severe HTG as fasting TG ≥5.6 mmol/L (≥500 mg/dL).[2] Different guidelines and societies have different thresholds for classification of HTG and consulting local guidance may be appropriate.[8][10][11]

Measurement of apolipoprotein B (apoB) is becoming more available and more popular; however, there are currently no universal standards. ApoB measurement is stable irrespective of fasting status and provides an integrated index of all atherogenic lipoproteins, including LDL, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and TG-rich remnant particles and lipoprotein(a).[24] Determination is not affected by fasting and can provide an indirect index of LDL particle size.

Whole blood samples from an individual with chylomicronaemia may appear milky-white if left to sit overnight.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Lipaemic blood sample taken from a patient within 24 hours of presentation. Blood samples may appear milky-white if triglyceride levels are very highFrom the personal collection of Professor Hegele, used with permission [Citation ends].

Subsequent investigations

Secondary causes for HTG should be routinely sought, including laboratory tests for hypothyroidism, diabetes, renal insufficiency, hypoalbuminaemia, or liver dysfunction.[47] Abdominal ultrasound can help detect steatotic (fatty) liver. Pursuing cardiac imaging to assess coronary blood flow and myocardial perfusion would depend on the development of concomitant symptoms and signs of ischaemic heart disease or ASCVD.[54]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer