Approach

Characteristic history and physical exam findings are usually sufficient for diagnosis and grading of injury. Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful for identifying concomitant knee pathology and the location of ligament injury. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Diagnostic algorithm for medial collateral ligament injuries. RICE: rest, ice, compression, elevationCreated by Sanjeev Bhatia, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

History

The precise mechanism of injury is established because determining the vector of force during injury helps identify the likely site of pathology. Excessive valgus stress on the knee is the most common mechanism for medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury. Often this valgus load results from a contact force on the lateral aspect of the lower thigh (e.g., during a tackle in sports such as American football or rugby). Noncontact valgus stress injuries are also common in sports such as skiing and are often combined with an external rotational element. The knee is frequently partly flexed at the time of injury.

Additional information that is important to obtain from the history includes the timeframe of injury, location of pain and tenderness, ability to ambulate after injury, any sensation of a pop or a tear (may indicate a more serious injury), time and onset of knee swelling, and presence of a deformity.[19] A common feature of MCL injuries is pain and stiffness on the medial side of the knee; patients with less severe injuries can typically still mobilize and do not have mechanical symptoms such as locking. Most low-grade MCL injuries are not associated with knee swelling. The timeframe of injury helps distinguish acute from chronic injury (chronic is defined as MCL injury ≥3 months from initial injury event).[4] Pain and tenderness usually corresponds to the site of knee pathology.[15]

Concurrent injuries commonly include bone bruises, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, lateral collateral ligament tears, medial meniscus tears, lateral meniscus tears, and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tears.[20] Questioning should explore the presence of mechanical symptoms, such as knee locking or giving way, which can help in the diagnosis of concomitant meniscal or other ligament pathology.

Physical exam

The goal of the physical exam is to confirm MCL injury, assess severity, and diagnose associated injuries. Knee exam (9 of 27): inspection & palpation: supine Opens in new window The injured knee should first be inspected and palpated in a systematic manner. Knee exam (14 of 27): MCL Opens in new window The presence and location of point tenderness, knee effusion or localized soft-tissue swelling, deformity, and/or ecchymosis should be noted. Time elapsed from injury to onset of swelling provides clues to the pathology involved: an acute effusion, occurring within 2 hours of injury, suggests hemarthrosis; swelling 12 to 24 hours after injury usually indicates a synovial effusion.[18] The presence of hemarthrosis is suspicious for an ACL injury. The site of injury along the superficial MCL usually correlates closely with the location of edema and tenderness.[15]

The integrity of the MCL is evaluated by assessing medial instability with the abduction stress test. The injured knee is flexed to 30 degrees and, with the knee stabilized, the ankle is gently abducted. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The abduction (valgus) stress testFrom the collection of Sanjeev Bhatia, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. The degree of laxity (in mm) and the quality of the end point should be noted. A firm end point (i.e., resistance is felt) indicates an intact MCL; a torn ligament is associated with a soft end point. The findings from the injured knee should be compared with the uninjured knee as a control. If the injured knee abducts more than the uninjured knee, the test is positive. MCL injuries are classified based on the amount of medial joint opening when a valgus load is applied at 20 to 30 degrees of knee flexion:[2]

The degree of laxity (in mm) and the quality of the end point should be noted. A firm end point (i.e., resistance is felt) indicates an intact MCL; a torn ligament is associated with a soft end point. The findings from the injured knee should be compared with the uninjured knee as a control. If the injured knee abducts more than the uninjured knee, the test is positive. MCL injuries are classified based on the amount of medial joint opening when a valgus load is applied at 20 to 30 degrees of knee flexion:[2]

Grade I: 0 to 5 mm of opening

Grade II: 5 to 10 mm of opening

Grade III: >10 mm of opening

The examination is then repeated in full extension to recruit contributions of posteromedial structures. A positive abduction stress test in full leg extension is highly suspicious for an ACL or PCL injury. The patient's feet should be maintained in the same degree of external rotation as was used during the flexed abduction stress testing in order to reduce false-positive results.

Tests should also be performed to rule out concomitant knee pathology.

The anterior drawer test [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The anterior drawer testFrom the collection of Sanjeev Bhatia, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

is the most reliable method for evaluating anteromedial rotatory instability, which can be present with or without an associated ACL injury.[21] This test is performed with the foot in external rotation and knee flexed at 90 degrees. Any laxity seen with an anterior pull on the proximal calf is positive for anteromedial instability, usually brought on with damage to the posterior oblique portion of the MCL.

is the most reliable method for evaluating anteromedial rotatory instability, which can be present with or without an associated ACL injury.[21] This test is performed with the foot in external rotation and knee flexed at 90 degrees. Any laxity seen with an anterior pull on the proximal calf is positive for anteromedial instability, usually brought on with damage to the posterior oblique portion of the MCL. The posterior drawer test, performed the same way but with a push on the tibia, is sensitive for PCL injury.

The Lachman test [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The Lachman testFrom the collection of Sanjeev Bhatia, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

is good for evaluating the ACL, even if the MCL has also been injured.[22] The knee is put in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion. The clinician uses one hand to hold the lower thigh above the knee and the other hand holds around the upper tibia (with the thumb on the tibial tuberosity). The tibia is then pulled anteriorly. An intact ACL will give a firm end point, preventing any forward translation. A torn ACL will demonstrate a soft end point by allowing more than 2 mm of anterior translation, as compared with the contralateral knee.

is good for evaluating the ACL, even if the MCL has also been injured.[22] The knee is put in 20 to 30 degrees of flexion. The clinician uses one hand to hold the lower thigh above the knee and the other hand holds around the upper tibia (with the thumb on the tibial tuberosity). The tibia is then pulled anteriorly. An intact ACL will give a firm end point, preventing any forward translation. A torn ACL will demonstrate a soft end point by allowing more than 2 mm of anterior translation, as compared with the contralateral knee. The pivot shift test can also be used for diagnosing an ACL tear. Internal rotation and valgus stress is applied on the knee while taking it from 20 to 40 degrees of flexion. In an ACL-deficient knee, the tibia anterolaterally subluxes in the initial phase of flexion and then reduces with further flexion. Tenderness on the joint line suggests meniscal injury.

Early referral to an orthopedic specialist is recommended for grade III MCL tears, a positive anterior drawer test, suspected multiligament injury, meniscal pathology, fractures, or any difficulty with diagnosis.

Diagnostic tests

Plain x-rays of the knee are ordered according to the Ottawa knee rules. Any one of the listed indications is sufficient to order an x-ray. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: X-ray indications in acute knee injury: the Ottawa knee rulesTable created by Sanjeev Bhatia, MD. Adapted from Stiell IG, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa knee rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. JAMA. 1997;278:2075-2079 [Citation ends].

Stress radiography, with a valgus stress placed on the knee at 15 to 20 degrees of flexion, is not routinely used for diagnosis or grading of injury as the diagnostic yield in grade I and II injuries is low. However, with grade III injuries in adolescents, stress radiography may help visualize the opening on the medial side of the joint and should be ordered in these patients as these x-rays can also help rule out physeal injury in this age group. Stress radiography is also useful in adults to help identify a grade III injury. A grade III MCL injury should be suspected in situations in which valgus stress radiography demonstrates a greater than 3.2 mm side-to-side difference of medial compartment gapping when comparing the noninjured knee to the injured knee at 20 degrees of flexion.[23] Radiography also identifies fractures of the tibial plateau, patella, or distal femur.

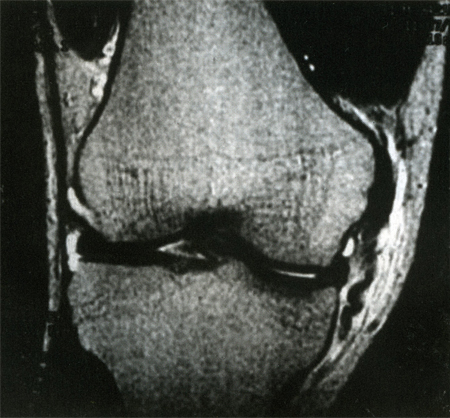

Stress radiography, with a valgus stress placed on the knee at 15 to 20 degrees of flexion, is not routinely used for diagnosis or grading of injury as the diagnostic yield in grade I and II injuries is low. However, with grade III injuries in adolescents, stress radiography may help visualize the opening on the medial side of the joint and should be ordered in these patients as these x-rays can also help rule out physeal injury in this age group. Stress radiography is also useful in adults to help identify a grade III injury. A grade III MCL injury should be suspected in situations in which valgus stress radiography demonstrates a greater than 3.2 mm side-to-side difference of medial compartment gapping when comparing the noninjured knee to the injured knee at 20 degrees of flexion.[23] Radiography also identifies fractures of the tibial plateau, patella, or distal femur. MRI provides excellent visualization of soft tissue anatomy and is indicated if injury to the menisci, ACL, or PCL is suspected. MRI can also indicate the presence of bone bruises or osteochondral fractures. MRI is useful for identifying the site of an MCL tear, [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: T2-weighted MRI showing a medial collateral ligament injuryFrom the collection of Sanjeev Bhatia, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

but is not an accurate method for determining grade of injury.

but is not an accurate method for determining grade of injury. Diagnostic ultrasound can also be used to evaluate soft tissue knee injuries, although MRI currently remains a more reliably accurate diagnostic modality.[24][25]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer