The main goal of treatment is to exclude the aneurysm sac from the intracranial circulation while preserving the parent artery. In unruptured aneurysms, the decision as to whether to treat or observe the aneurysm is made on a case-by-case basis.[39]Etminan N, Brown RD Jr, Beseoglu K, et al. The unruptured intracranial aneurysm treatment score: a multidisciplinary consensus. Neurology. 2015 Sep 8;85(10):881-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4560059

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26276380?tool=bestpractice.com

In ruptured aneurysms, early treatment is essential. Interventional therapy involves either microsurgical clipping or endovascular techniques.

Surgery for cerebral aneurysm involves placing a clip across the neck of an intracranial aneurysm and has a long track record of demonstrated efficacy. The attributable risk of the procedure is fairly low.[8]Schievink WI. Intracranial aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jan 2;336(1):28-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8970938?tool=bestpractice.com

The size, location, and configuration of the aneurysm, along with brain edema, vasospasm, and surrounding tenacious clot, all complicate microsurgical clipping and can increase procedural complications.

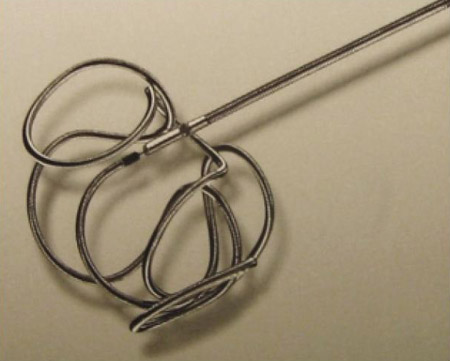

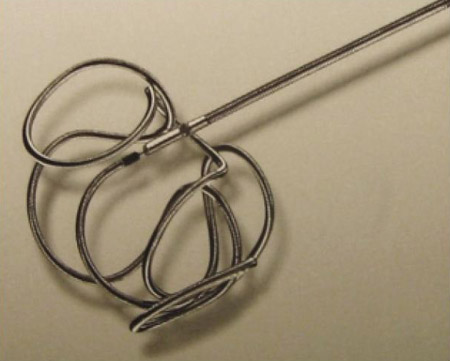

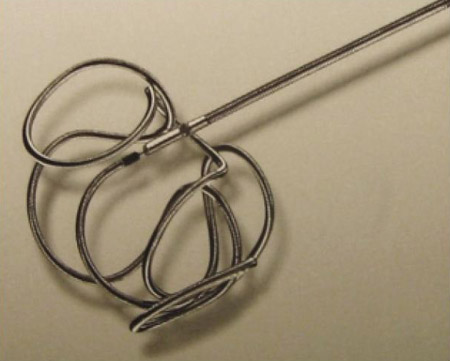

Standard endovascular therapy for cerebral aneurysms involves insertion of soft metallic coils within the lumen of the aneurysm, which are detached once they are in place.[40]Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Sepetka I, et al. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach. Part 1: Electrochemical basis, technique, and experimental results. J Neurosurg. 1991 Jul;75(1):1-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2045891?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Example of a coil used to treat cerebral aneurysmsFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

The coils, some bare platinum, some with various surface additives, all promote thrombosis within the aneurysm dome.[41]Kurre W, Berkefeld J. Materials and techniques for coiling of cerebral aneurysms: how much scientific evidence do we have? Neuroradiology. 2008 Nov;50(11):909-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18802691?tool=bestpractice.com

A comparison of hydrogel-coated coils versus bare platinum coils did not show an improvement in long-term clinical outcomes with the coated device, although it did seem to reduce major recurrence.[42]White PM, Lewis SC, Gholkar A, et al; HELPS trial collaborators. Hydrogel-coated coils versus bare platinum coils for the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms (HELPS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011 May 14;377(9778):1655-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21571149?tool=bestpractice.com

Factors that complicate endovascular treatment are a wide neck, a giant aneurysm with intra-aneurysm thrombus, and the presence of eloquent arterial branches emanating from the aneurysm dome. Adjunctive devices, such as balloons and intracranial stents, can enable aneurysms that were previously difficult to coil to be successfully treated, and alternative novel endovascular devices may be considered for selected patients.[43]Bodily KD, Cloft HJ, Lanzino G, et al. Stent-assisted coiling in acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a qualitative, systematic review of the literature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011 Aug;32(7):1232-6.

http://www.ajnr.org/content/32/7/1232.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21546464?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Etminan N, de Sousa DA, Tiseo C, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur Stroke J. 2022 Sep;7(3):V.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23969873221099736

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36082246?tool=bestpractice.com

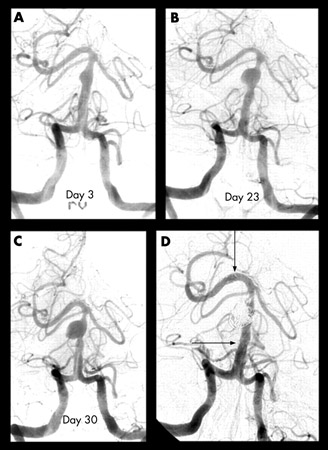

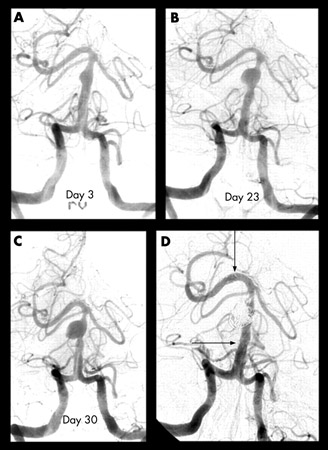

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Progressive angiography images of a small dissecting aneurysm of the distal basilar artery after a subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage on day 3 (A), day 23 (B), and day 30 (C), and 6 months after stent-assisted coiling (D). Arrows indicate proximal and distal stent markersFrom: Peluso JP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.121533. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Unruptured aneurysms

For aneurysms that have not ruptured, the choice for management is observation or treatment.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

Observation consists of periodic imaging studies of increasingly greater duration along with regular visits to the physician. Treatment consists of either open surgical clipping or endovascular obliteration.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

A 2021 systematic review concluded there is currently insufficient evidence to support either conservative treatment (e.g., treating risk factors, such as hypertension, and smoking cessation) or interventional treatments (microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling) for individuals with unruptured intracranial aneurysms.[45]Pontes FGB, da Silva EM, Baptista-Silva JC, et al. Treatments for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 10;5:CD013312.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013312.pub2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33971026?tool=bestpractice.com

The choice of observation or treatment needs to be made on a case-by-case basis by a specialist experienced in the management of cerebral aneurysms. Treatment may be pursued when the lifetime risk of rupture is felt to exceed the risk of proposed treatment approach.[44]Etminan N, de Sousa DA, Tiseo C, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur Stroke J. 2022 Sep;7(3):V.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23969873221099736

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36082246?tool=bestpractice.com

Factors to consider include:

Age: increased risk of treatment and shorter life expectancy tend to favor observation in older patients with asymptomatic aneurysms.

Location: the risk of rupture varies depending on the location of the aneurysm. Cavernous carotid artery aneurysms carry the lowest risk, anterior circulation aneurysms carry an intermediate risk, and posterior circulation aneurysms carry the highest risk of rupture.

Personal history of subarachnoid hemorrhage: prior aneurysmal hemorrhage is an independent risk factor of rupture of additional aneurysms, regardless of size.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

Size: the risk of rupture increases with the size of the aneurysm. In asymptomatic patients without a history of subarachnoid hemorrhage, small aneurysms (i.e., <7 mm) can generally be observed.[2]Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J 3rd, et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362:103-110.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12867109?tool=bestpractice.com

Stability: interval enlargement (>1 mm) is a strong risk factor for rupture and treatment is recommended even when overall size remains small.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

Symptoms: symptomatic aneurysms should be considered for treatment regardless of size. Urgent consideration for treatment is needed for symptomatic intradural aneurysms.

Comorbidities: increases the risk of treatment.

Risks of treatment: the two main risks are surgery-related death and poor neurologic outcomes.

Clinicians should be aware of the psychological burden of deferring interventional treatment of small unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Patient anxiety about a "ticking time bomb" should be addressed where appropriate and incorporated into the shared decision-making process.[46]Jelen MB, Clarke RE, Jones B, et al. Psychological and functional impact of a small unruptured intracranial aneurysm diagnosis: a mixed‐methods evaluation of the patient journey. Stroke vasc. interv. neurol. 2022 Sep 26;3(1):e000531.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/SVIN.122.000531#d1e2147

For unruptured aneurysms, there is insufficient evidence to support a preference for either surgical clipping or endovascular coiling, and selection should be based on individual patient factors.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Etminan N, de Sousa DA, Tiseo C, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur Stroke J. 2022 Sep;7(3):V.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23969873221099736

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36082246?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]Pontes FGB, da Silva EM, Baptista-Silva JC, et al. Treatments for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 May 10;5:CD013312.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013312.pub2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33971026?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition, novel endovascular devices may be considered for high-risk unruptured cerebral aneurysms (e.g., wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms) not suitable for standard interventional treatments; however, there is a low certainty of evidence for use of these devices:[44]Etminan N, de Sousa DA, Tiseo C, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur Stroke J. 2022 Sep;7(3):V.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/23969873221099736

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36082246?tool=bestpractice.com

Flow-diverter devices channel blood flow away from the aneurysm through a stent sited across the aneurysm neck.[47]Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013 Feb;44(2):442-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23321438?tool=bestpractice.com

Evidence shows that treatment of cerebral aneurysms with flow-diverter devices is an effective endovascular procedure with high complete occlusion rates.[47]Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Lanzino G, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013 Feb;44(2):442-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23321438?tool=bestpractice.com

These devices carry a risk of device-associated thrombotic complications and require the use of dual antiplatelet medications. Antithrombogenic surface modifications may reduce the risk of ischemic complications.[48]Li YL, Roalfe A, Chu EY, et al. Outcome of flow diverters with surface modifications in treatment of cerebral aneurysms: systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2021 Jan;42(2):327-33.

https://www.ajnr.org/content/42/2/327

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33384292?tool=bestpractice.com

Intrasaccular flow disruptors (e.g., Contour or WEB devices) can be deployed within the aneurysm.[49]Lee KB, Suh CH, Song Y, et al. Trends of expanding indications of woven EndoBridge devices for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neuroradiol. 2023 Mar;33(1):227-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36036257?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Liebig T, Killer-Oberpfalzer M, Gal G, et al. The safety and effectiveness of the contour neurovascular system (contour) for the treatment of bifurcation aneurysms: the CERUS study. Neurosurgery. 2022 Mar 1;90(3):270-7.

https://journals.lww.com/neurosurgery/Fulltext/2022/03000/The_Safety_and_Effectiveness_of_the_Contour.3.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35113830?tool=bestpractice.com

When placed entirely intrasaccular, dual antiplatelet medications are not required. These treatments have a favorable procedural safety profile compared to traditional techniques; however, the rates of complete aneurysm occlusion at one year (50%) fall short of other treatment modalities and long-term outcomes have not been established.[51]Chen CJ, Dabhi N, Snyder MH, et al. Intrasaccular flow disruption for brain aneurysms: a systematic review of long-term outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2021 Dec 24;1-13.

https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/137/2/article-p360.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34952523?tool=bestpractice.com

Ruptured aneurysms

Treatment with endovascular coiling or microsurgical clipping should be instituted as early as possible for the majority of patients with a ruptured aneurysm.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm: diagnosis and management. Nov 2022 [nternet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng228

Complete obliteration of the aneurysm is recommended whenever possible.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment of unruptured coexisting aneurysms should also be considered.

The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) compared the safety and efficacy of endovascular coil treatment and surgical clipping for the treatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms.[52]Molyneux A, Kerr R, Stratton I, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002 Oct 26;360(9342):1267-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12414200?tool=bestpractice.com

The primary results of ISAT were that, among patients equally suited for both treatment options, endovascular coil treatment yielded substantially better outcomes than surgery in terms of survival free of disability at 1 year. A follow-up study of the ISAT participants demonstrated that endovascular coil treatment was also associated with increased long-term survival (at 10 years) when compared with neurosurgical repair.[53]Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, et al. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). Lancet. 2015 Feb 21;385(9969):691-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4356153

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25465111?tool=bestpractice.com

Data from a 2018 systematic review on randomized trials has shown that for patients in good clinical condition with ruptured aneurysms, coiling is associated with a better outcome than surgery. No consistent trial evidence exists for patients in a poor clinical condition.[54]Lindgren A, Vergouwen MD, van der Schaaf I, et al. Endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping for people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Aug 15;8:CD003085.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003085.pub3

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30110521?tool=bestpractice.com

Extracranial-intracranial bypass can be considered if a clip application or coiling procedure cannot be performed.[55]Schaller B. Extracranial-intracranial bypass to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke in intracranial aneurysms of the anterior cerebral circulation: a systematic review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008 Sep;17(5):287-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18755409?tool=bestpractice.com

Flow-diverter devices are not recommended for ruptured cerebral aneurysms due to a high rate of observed complications including aneurysm re-rupture, device thrombosis, and complications of associated dual antiplatelet therapy, and should only be considered when no other method of effective aneurysm treatment is feasible.[56]Giorgianni A, Agosti E, Molinaro S, et al. Flow diversion for acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms treatment: a retrospective study and literature review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2022 Mar;31(3):106284.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35007933?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Ten Brinck MFM, Jäger M, de Vries J, et al. Flow diversion treatment for acutely ruptured aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020 Mar;12(3):283-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31446429?tool=bestpractice.com

Current data suggest intrasaccular flow disruptors may be as safe in ruptured aneurysms as unruptured aneurysms, but limitations on their long-term occlusion rates preclude their routine recommendation over established methods.[58]Diestro JDB, Dibas M, Adeeb N, et al. Intrasaccular flow disruption for ruptured aneurysms: an international multicenter study. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022 Jul 22;neurintsurg-2022-019153. [Epub ahead of print].

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35868856?tool=bestpractice.com

See Subarachnoid hemorrhage for further information on management of ruptured cerebral aneurysms.

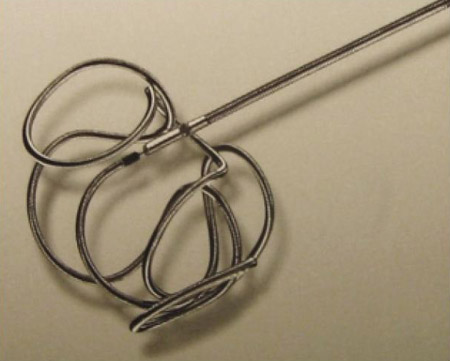

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Example of a coil used to treat cerebral aneurysmsFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

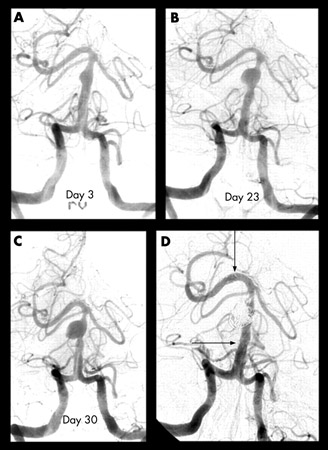

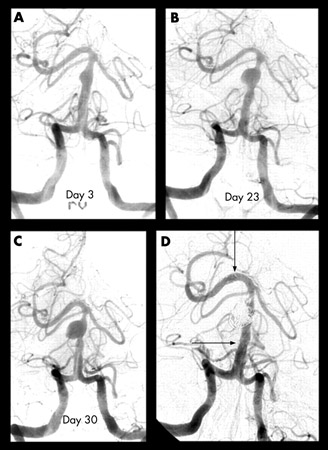

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Progressive angiography images of a small dissecting aneurysm of the distal basilar artery after a subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage on day 3 (A), day 23 (B), and day 30 (C), and 6 months after stent-assisted coiling (D). Arrows indicate proximal and distal stent markersFrom: Peluso JP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.121533. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Supportive care for ruptured aneurysms

The patient should be monitored closely for complications such as hydrocephalus or cerebral vasospasm in a quiet room in the neurointensive care unit. If the patient is agitated, mild sedation is recommended. The head end of the bed should be kept raised to around 30°.

Consciousness level should be assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale, and need for endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation should be established. Blood pressure (BP), heart rate, and respiratory function should be closely monitored.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

Despite concern that extreme blood pressures might precipitate rebleeding events, the specific parameters and methods of high BP treatment in the acute phase have not been established. When patients are severely hypertensive (>180-200 mmHg), BP should be gradually controlled while balancing the risk of low cerebral or systemic perfusion and cerebral vasospasm. A target systolic BP <160 mmHg (or mean arterial pressure <110 mmHg) is reasonable, but patient-specific factors such as BP at presentation, brain edema, hydrocephalus, and history of hypertension and renal impairment should be considered when deciding on an individualized BP target.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Diringer MN, Bleck TP, Claude Hemphill J 3rd, et al. Critical care management of patients following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: recommendations from the Neurocritical Care Society's Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference. Neurocrit Care. 2011 Sep;15(2):211-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21773873?tool=bestpractice.com

Calcium-channel blockade with nimodipine is given to all patients.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm: diagnosis and management. Nov 2022 [nternet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng228

Patients with vasospasm not responding rapidly to hypertensive therapy may require cerebral angioplasty and intra-arterial vasodilation with calcium-channel blockers.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

Stool softeners are given to prevent Valsalva maneuvers that may cause peaks in systolic BP and intrathoracic pressure.