Patients with an unruptured cerebral aneurysm may be asymptomatic. As the aneurysm increases in size it may cause symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (such as headaches and vomiting) or focal cranial nerve lesions. Rupture of a cerebral aneurysm with resulting subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is the most feared clinical manifestation of cerebral aneurysms.

History

Unruptured aneurysms are often asymptomatic and are usually detected either incidentally or on screening.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

Aneurysms can rupture at any time, but rupture may be associated with exertion or stress.[19]Schievink WI, Karemaker JM, Hageman LM, et al. Circumstances surrounding aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 1989 Oct;32(4):266-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2675363?tool=bestpractice.com

An unusual, unexpected abrupt-onset headache is the most common symptom of an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and may be accompanied by other symptoms including nausea and/or vomiting, and possibly an abrupt change in consciousness.[19]Schievink WI, Karemaker JM, Hageman LM, et al. Circumstances surrounding aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 1989 Oct;32(4):266-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2675363?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm: diagnosis and management. Nov 2022 [nternet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng228

Patients sometimes report an unusual headache several weeks prior, which may represent a minor leak of blood into the wall of the aneurysm or into the subarachnoid space (known as a sentinel headache).[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Leblanc R. The minor leak preceding subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1987 Jan;66(1):35-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3783257?tool=bestpractice.com

In some cases the severity of the headache can be quite mild and misleading. Speed of onset may be as significant as severity, and in every patient complaining of a new headache SAH should be considered as an important secondary cause and be investigated when appropriate.[23]van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 2007 Jan 27;369(9558):306-18.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17258671?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

In an unruptured aneurysm, the examination is usually unremarkable. However, a pressure effect from the aneurysm may produce focal neurological signs.[24]Brisman JL, Song JK, Newell DW. Cerebral aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 31;355(9):928-39.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16943405?tool=bestpractice.com

The classic syndrome is that of a third nerve palsy with pupillary dysfunction from a posterior communicating artery aneurysm exerting mass effect.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

In a ruptured aneurysm, findings depend on the severity and location of the SAH; there may be nuchal rigidity and intraocular hemorrhage. The neurological exam may be normal in an SAH, show focal neurological signs due to a local mass effect from a hematoma, or the patient may be in a deep coma with decerebrate rigidity.

Investigations

Computed tomography (CT) head without contrast is the preferred initial diagnostic test when SAH is suspected.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm: diagnosis and management. Nov 2022 [nternet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng228

Modern CT scanners are highly sensitive (92.9%) and specific (100%) for identifying patients with SAH, particularly if performed within 6 hours when sensitivity improves to 97% to 100%.[25]Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Sivilotti ML, et al. Sensitivity of computed tomography performed within six hours of onset of headache for diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011 Jul 18;343:d4277.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3138338

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21768192?tool=bestpractice.com

It is reasonable to exclude SAH if a scan performed within 6 hours does not show subarachnoid blood.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

If there is high clinical suspicion for SAH but the CT scan was performed after 6 hours, a lumbar puncture should be performed.[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm: diagnosis and management. Nov 2022 [nternet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng228

Grossly bloody cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that does not clear suggests SAH. A more definitive finding is the presence of xanthochromia, a yellowish discoloration of CSF caused by breakdown products of hemoglobin. This usually takes about 12 hours to develop.[26]Edlow JA, Caplan LR. Avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 6;342(1):29-36.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10620647?tool=bestpractice.com

Cerebral angiography (conventional catheter-based digital subtraction angiography, CT angiography [CTA], or magnetic resonance angiography [MRA]) is used to delineate the causative aneurysm and direct appropriate definitive management.

Conventional cerebral angiography is still the preferred imaging modality for a cerebral aneurysm, ruptured or unruptured.[18]Thompson BG, Brown RD Jr, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015 Aug;46(8):2368-400.

http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/46/8/2368.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26089327?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, et al. 2023 Guideline for the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2023 Jul;54(7):e314-70.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000436

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37212182?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging., Ledbetter LN, Burns J, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Cerebrovascular diseases - aneurysm, vascular malformation, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11s):S283-S304.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.08.012

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794589?tool=bestpractice.com

With a resolution of 50 micrometers, conventional cerebral angiography, including 3-dimensional reconstructions, not only has the highest sensitivity but also allows for better characterization of the morphology, orientation, neck size, adjacent vessels, and any additional aneurysms.

Both CTA and MRA demonstrate high specificity in detecting aneurysms >3 mm.[27]Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging., Ledbetter LN, Burns J, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Cerebrovascular diseases - aneurysm, vascular malformation, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Nov;18(11s):S283-S304.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2021.08.012

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34794589?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Menke J, Larsen J, Kallenberg K. Diagnosing cerebral aneurysms by computed tomographic angiography: meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2011 Apr;69(4):646-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21391230?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Sailer AM, Wagemans BA, Nelemans PJ, et al. Diagnosing intracranial aneurysms with MR angiography: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2014 Jan;45(1):119-26.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003133

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24326447?tool=bestpractice.com

CTA can be useful in acute situations because it can be obtained quickly and help guide the decision making and urgency of subsequent studies. MRA takes longer to perform than CTA and is therefore less appropriate for critically ill patients.[29]Sailer AM, Wagemans BA, Nelemans PJ, et al. Diagnosing intracranial aneurysms with MR angiography: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2014 Jan;45(1):119-26.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003133

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24326447?tool=bestpractice.com

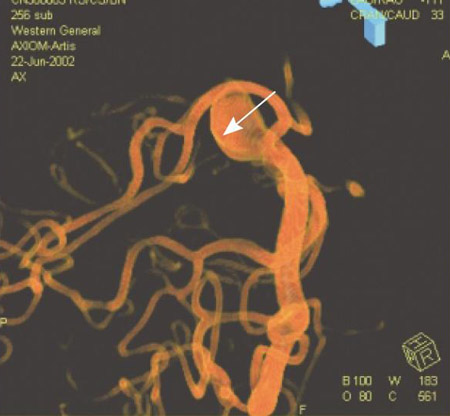

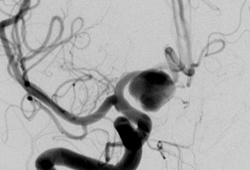

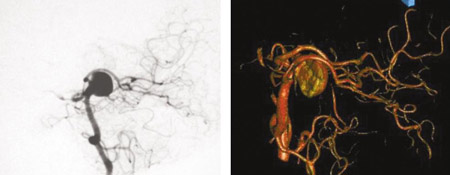

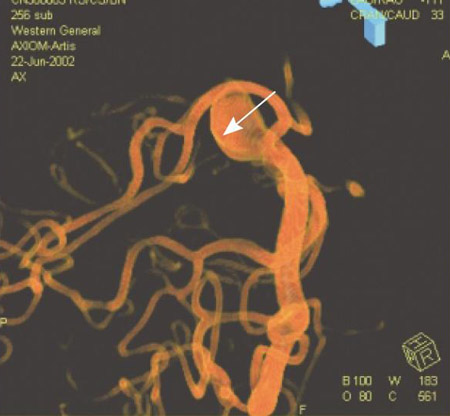

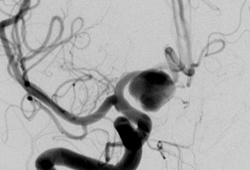

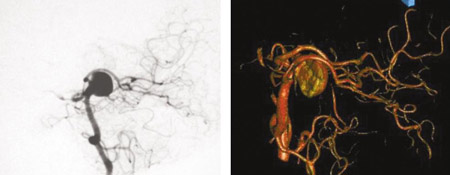

MRA does not carry the risk of ionizing radiation and can be obtained without contrast using time of flight techniques (MRA-TOF). MRA is preferred for screening and serially monitoring unruptured aneurysms. Both CTA and MRA are limited in identifying features and morphology of small (<3 mm aneurysms), and are susceptible to prominent artifacts from prior aneurysm treatments (metallic clips, coils, stents).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cerebral angiogram showing aneurysmFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Chen, Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comparison of 2-dimensional catheter angiography (left) with 3-dimensional catheter angiography (right) showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comparison of 2-dimensional catheter angiography (left) with 3-dimensional catheter angiography (right) showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three-dimensional catheter angiogram showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three-dimensional catheter angiogram showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Emerging investigations

MRA vessel wall imaging (VWI) is an emerging tool for the risk stratification of aneurysms, utilizing contrast and high resolution to observe enhancement within the wall of the artery, which may imply instability or inflammation.[30]Samaniego EA, Roa JA, Hasan D. Vessel wall imaging in intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019 Nov;11(11):1105-12.

https://jnis.bmj.com/content/11/11/1105

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31337731?tool=bestpractice.com

Lack of enhancement has been shown to be strongly predictive of aneurysm stability, but positive enhancement is poorly predictive of instability and many enhancing aneurysms are also stable.[31]Texakalidis P, Hilditch CA, Lehman V, et al. Vessel wall imaging of intracranial aneurysms: systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2018 Sep;117:453-8.e1.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29902602?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Molenberg R, Aalbers MW, Appelman APA, et al. Intracranial aneurysm wall enhancement as an indicator of instability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. 2021 Nov;28(11):3837-48.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ene.15046

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34424585?tool=bestpractice.com

Multiple limitations including lack of standardized protocols, variation in the definition of aneurysmal enhancement, and the need for experienced neuroradiologists to interpret the study prevent widespread use, and further validation is required.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comparison of 2-dimensional catheter angiography (left) with 3-dimensional catheter angiography (right) showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Comparison of 2-dimensional catheter angiography (left) with 3-dimensional catheter angiography (right) showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three-dimensional catheter angiogram showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Three-dimensional catheter angiogram showing a basilar tip aneurysmFrom: Sellar M. Practical Neurology. 2005;5:28-37. Used with permission [Citation ends].