Treatment is directed at any identified underlying disorder with supportive management directed at relief of symptoms. Hospitalization is generally recommended to determine etiology where possible, observe for complications such as cardiac tamponade, and gauge response to therapy.

Initial management of patients with suspected pericarditis

Any patient with a clinical presentation that suggests an underlying etiology should be admitted to hospital for further investigation and treatment.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with at least one predictor of poor prognosis (major or minor risk factors below) should also be admitted.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

Major risk factors:

High fever (i.e., >100.4°F [>38°C])

Subacute course (i.e., symptoms over several days without a clear-cut acute onset)

Evidence of a large pericardial effusion (i.e., diastolic echo-free space >20 mm)

Cardiac tamponade

Failure to respond within 7 days to a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

Minor risk factors:

Patients with any of these risk factors warrant careful observation and follow-up. Some patients without any of these features can be managed as an outpatient if considered appropriate. In these cases, the patient should be started on treatment (i.e., empiric anti-inflammatories) with follow-up after 1 week to assess the response to treatment.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

Pericardial effusion

If a pericardial effusion is present, pericardiocentesis is indicated for clinical tamponade, for high suspicion of purulent or neoplastic pericarditis, or if the effusion is large or symptomatic.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

In the absence of these indications, medical therapy is started as dictated by the cause.

Purulent disease

Purulent pericarditis is immediately life-threatening and requires immediate confirmation of diagnosis via urgent pericardiocentesis. Pericardial fluid should be tested for bacterial, fungal, and tuberculous causes, and blood should be drawn for culture.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

If purulent pericarditis is suspected, urgent percutaneous pericardiocentesis with rinsing of the pericardial cavity and intravenous antibiotics are mandatory. Empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy is recommended until microbiologic results are available.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

There are limited data available to guide antibiotic selection, but experts typically recommend a regimen that contains an antistaphylococcal antibiotic. The choice of antibiotics will depend on various factors including local resistance patterns and MRSA prevalence. Follow your local protocols and seek microbiology or infectious disease advice. Empiric therapy should be switched to tailored therapy depending on the underlying pathogens identified from pericardial fluid and blood cultures.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

Therapy with systemic antibiotics should be continued until fever and clinical signs of infection, including leukocytosis, have resolved.[3]Imazio M, Brucato A, Mayosi BM, et al. Medical therapy of pericardial diseases: part I: idiopathic and infectious pericarditis. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010 Oct;11(10):712-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20736783?tool=bestpractice.com

An NSAID should also be started on diagnosis for symptom management with a proton-pump inhibitor to reduce gastrointestinal adverse effects; the dose should be tapered after 1-2 weeks according to symptoms.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28;113(12):1622-32.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/113/12/1622

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16567581?tool=bestpractice.com

Acetaminophen or an opioid can be considered if NSAIDs are not effective or are contraindicated. Colchicine should only be used with caution in patients with purulent pericarditis as it may interfere with leukocyte function and infection clearance.[54]McEwan T, Robinson PC. A systematic review of the infectious complications of colchicine and the use of colchicine to treat infections. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021 Feb;51(1):101-12.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.11.007

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33360321?tool=bestpractice.com

Open surgical drainage via a subxiphoid pericardiotomy is also required.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

Pericardiectomy in these patients is necessary in the presence of dense adhesions or loculations, persistent bacteremia, recurrent tamponade, or progression to constrictive physiology.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

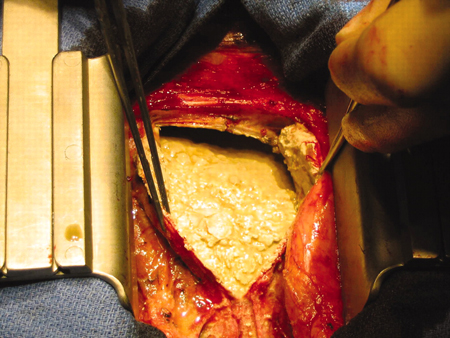

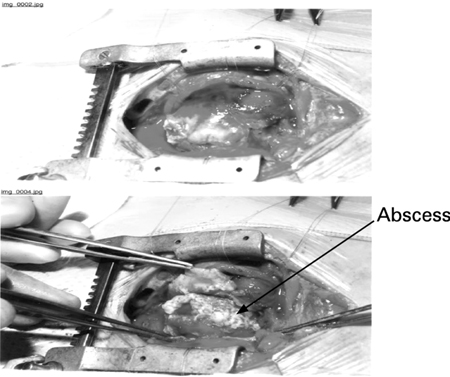

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Open surgery in a baby with purulent pericarditis; the abscess is indicated by the arrowKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

Exercise should be restricted until chest pain resolves and inflammatory markers have normalized.[55]Kim JH, Baggish AL, Levine BD, et al. Clinical considerations for competitive sports participation for athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2025 Feb 20 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001297

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39973614?tool=bestpractice.com

A minimum of 3 months is often considered appropriate (and recommended for patients involved in competitive sports), but shorter periods of exercise restriction may be considered depending on patient and disease characteristics (e.g., nonathletes and/or mild clinical picture).[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28;113(12):1622-32.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/113/12/1622

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16567581?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Pelliccia A, Solberg EE, Papadakis M, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive and leisure time sport in athletes with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, and pericarditis: position statement of the Sport Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J. 2019 Jan 1;40(1):19-33.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/40/1/19/5248228

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30561613?tool=bestpractice.com

Nonpurulent disease: first presentation

NSAIDs are given for symptom relief.[16]Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Jun;85(6):572-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20511488?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015 Oct 13;314(14):1498-506.

https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1576078#.XAFHbdv7S70

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26461998?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Galluzzo A, Imazio M. Advances in medical therapy for pericardial diseases. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018 Sep;16(9):635-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30103638?tool=bestpractice.com

They reduce fever, chest pain, and inflammation but do not prevent tamponade, constriction, or recurrent pericarditis.[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Imazio M, Brucato A, Trinchero R, et al. Diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 Dec;6(12):743-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19859068?tool=bestpractice.com

NSAIDs are given with a proton-pump inhibitor to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects (e.g., ulcer formation); consider tapering the dose after 1-2 weeks according to symptoms.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28;113(12):1622-32.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/113/12/1622

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16567581?tool=bestpractice.com

Ibuprofen is frequently used because of its favorable side-effect profile compared with other drugs in this class; however, choice of drug should be based on patient characteristics (e.g., contraindications, previous efficacy, or adverse effects) and physician expertise.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jan 7;75(1):76-92.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109719384840?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31918837?tool=bestpractice.com

Aspirin is preferred if required for persistent symptoms due to early pericarditis or late pericarditis post-myocardial infarction (MI) as other NSAIDs adversely affect myocardial healing, and for its antiplatelet activity. Glucocorticoids and NSAIDs (other than aspirin) are not indicated for post-MI pericarditis due to the potential for harm.[58]Rao SV, O'Donoghue ML, Ruel M, et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guideline for the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. Mar 2025 [internet publication].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001309

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40014670?tool=bestpractice.com

If NSAIDs or high-dose aspirin are not effective or are contraindicated, acetaminophen or an opioid may be considered.

Colchicine is recommended as a first-line adjunct therapy to NSAIDs as it improves response, decreases recurrences, and increases remission rates.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Andreis A, Imazio M, Casula M, et al. Colchicine efficacy and safety for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Intern Emerg Med. 2021 Sep;16(6):1691-700.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11739-021-02654-7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33704674?tool=bestpractice.com

It is given for 3 months in this setting.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015 Oct 13;314(14):1498-506.

https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1576078#.XAFHbdv7S70

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26461998?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Galluzzo A, Imazio M. Advances in medical therapy for pericardial diseases. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018 Sep;16(9):635-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30103638?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Bayes-Genis A, Adler Y, de Luna AB, et al. Colchicine in pericarditis. Eur Heart J. 2017 Jun 7;38(22):1706-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx246

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30052886?tool=bestpractice.com

The addition of colchicine should be considered in patients with postcardiotomy injury syndromes (e.g., Dressler syndrome, which generally occurs 1-2 weeks after an MI; or postcardiac surgery), provided there are no contraindications and it is well tolerated. Preventive administration is recommended for 1 month. Careful follow-up with echocardiography every 6 to 12 months according to clinical features and symptoms should be considered to exclude possible evolution towards constrictive pericarditis.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

In cases of idiopathic or postviral pericarditis, if chest pain has not resolved after 2 weeks, a corticosteroid can be considered as an option in patients who do not respond to anti-inflammatory therapy, or for patients in whom an NSAID is contraindicated, once an infectious cause has been excluded. Corticosteroids are not recommended in patients with viral pericarditis because of the risk of re-activation of the viral infection and ongoing inflammation. Corticosteroids may also be used when there is a specific indication for their use (e.g., the presence of an autoimmune disease). They are used in combination with colchicine for this indication. Corticosteroids are less favored compared with NSAIDs because of the risks of promoting chronic and/or recurrent disease, and side effects.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

If used, low to moderate doses are preferred over high doses.[18]Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jan 7;75(1):76-92.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109719384840?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31918837?tool=bestpractice.com

The initial dose should be maintained until symptoms have resolved and the C-reactive protein (CRP) level has normalized. Once this is achieved, the dose may be gradually tapered.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition to the above treatment, the underlying cause should also be treated if known. Underlying causes include viral infections (e.g., Coxsackie virus A9, B1-4, Echo 8, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella, rubella, HIV, Parvo-19, SARS-CoV-2), tuberculosis (a common cause in the developing world), secondary immune processes (e.g., rheumatic fever, postcardiotomy syndrome, post-MI syndrome), metabolic disorders (e.g., uremia, myxedema), radiation therapy, cardiac surgery, percutaneous cardiac interventions, systemic autoimmune disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, reactive arthritis, familial Mediterranean fever, systemic vasculitides, inflammatory bowel disease), bacterial/fungal/parasitic infections, trauma, certain drugs, and neoplasms.

In patients with tuberculous pericarditis, first-line treatment is 4 to 6 weeks of antituberculous therapy.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Imazio M, Brucato A, Mayosi BM, et al. Medical therapy of pericardial diseases: part I: idiopathic and infectious pericarditis. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010 Oct;11(10):712-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20736783?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura RA, et al. Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Jun;85(6):572-93.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20511488?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Imazio M, et al. International collaborative systematic review of controlled clinical trials on pharmacologic treatments for acute pericarditis and its recurrences. Am Heart J. 2010 Oct;160(4):662-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20934560?tool=bestpractice.com

When tuberculous pericarditis is confirmed in an nonendemic area, a suitable 6-month regimen is effective; empiric therapy is not required in the absence of an established diagnosis in nonendemic areas.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

Adjunctive therapies such as colchicine, corticosteroids, and immunotherapy have not been shown to be beneficial.[62]Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Bosch J, et al. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 18;371(12):1121-30.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1407380#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25178809?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]George IA, Thomas B, Sadhu JS. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adjunctive corticosteroids in the treatment of tuberculous pericarditis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018 May 1;22(5):551-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29663961?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Isiguzo G, Du Bruyn E, Howlett P, et al. Diagnosis and management of tuberculous pericarditis: what is new? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020 Jan 15;22(1):2.

https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s11886-020-1254-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31940097?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Liebenberg JJ, Dold CJ, Olivier LR. A prospective investigation into the effect of colchicine on tuberculous pericarditis. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2016 Nov/Dec;27(6):350-5.

https://www.doi.org/10.5830/CVJA-2016-035

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27965998?tool=bestpractice.com

However, corticosteroids may be considered in patients with tuberculous pericarditis who are HIV-negative.[66]Wiysonge CS, Ntsekhe M, Thabane L, et al. Interventions for treating tuberculous pericarditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 13;9:CD000526.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000526.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28902412?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of steroids for people with tuberculous pericarditis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1937/fullShow me the answer Pericardiectomy is recommended if the patient does not improve or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Yadav S, Shah S, Iqbal Z, et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive tuberculous pericarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the etiology, patients' characteristics, and the outcomes. Cureus. 2021 Sep;13(9):e18252.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8544905

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34722042?tool=bestpractice.com

Most patients with uremic pericarditis respond to intensive dialysis within 1 to 2 weeks. Autoimmune disorders are treated with corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive therapies depending on the specific condition. Treatment of neoplasms may involve any combination of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery, depending on the type of tumor identified.[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Imazio M, Brucato A, Trinchero R, et al. Diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 Dec;6(12):743-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19859068?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with viral pericarditis may benefit from specific antiviral therapy; however, an infectious disease attending should be involved.

]

What are the benefits and harms of steroids for people with tuberculous pericarditis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1937/fullShow me the answer Pericardiectomy is recommended if the patient does not improve or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Yadav S, Shah S, Iqbal Z, et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive tuberculous pericarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the etiology, patients' characteristics, and the outcomes. Cureus. 2021 Sep;13(9):e18252.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8544905

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34722042?tool=bestpractice.com

Most patients with uremic pericarditis respond to intensive dialysis within 1 to 2 weeks. Autoimmune disorders are treated with corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive therapies depending on the specific condition. Treatment of neoplasms may involve any combination of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery, depending on the type of tumor identified.[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Imazio M, Brucato A, Trinchero R, et al. Diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009 Dec;6(12):743-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19859068?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with viral pericarditis may benefit from specific antiviral therapy; however, an infectious disease attending should be involved.

Exercise should be restricted until chest pain resolves and inflammatory markers have normalized.[55]Kim JH, Baggish AL, Levine BD, et al. Clinical considerations for competitive sports participation for athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2025 Feb 20 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001297

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39973614?tool=bestpractice.com

A minimum of 3 months is often considered appropriate (and is recommended for those participating in competitive sports), but shorter periods of exercise restriction may be considered depending on patient and disease characteristics (e.g., nonathletes and/or mild clinical picture).[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28;113(12):1622-32.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/113/12/1622

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16567581?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Pelliccia A, Solberg EE, Papadakis M, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive and leisure time sport in athletes with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, and pericarditis: position statement of the Sport Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J. 2019 Jan 1;40(1):19-33.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/40/1/19/5248228

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30561613?tool=bestpractice.com

Nonpurulent disease: recurrent

For recurrent pericarditis, patients are treated with an NSAID plus colchicine, as well as exercise restriction. The NSAID should be continued until symptoms resolve, and the colchicine continued for 6 months to prevent recurrence. A longer duration of therapy for colchicine can be considered in resistant cases. CRP levels should be used to guide therapy and response. Once the CRP has normalized, drug therapy can be tapered gradually according to symptoms and the CRP level.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

For patients who do not respond to an NSAID plus colchicine, corticosteroid therapy can be considered as for patients at the initial presentation. Third-line therapies in recurrent disease are immunosuppressants, including intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), interleukin-1 inhibitors (anakinra, and rilonacept), and azathioprine.[68]Imazio M, Lazaros G, Gattorno M, et al. Anti-interleukin-1 agents for pericarditis: a primer for cardiologists. Eur Heart J. 2022 Aug 14;43(31):2946-57.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/31/2946/6370991

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34528670?tool=bestpractice.com

All are off-label for pericarditis, except for rilonacept which is approved for recurrent pericarditis (but not first presentations).[18]Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, et al. Management of acute and recurrent pericarditis: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jan 7;75(1):76-92.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109719384840?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31918837?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Kumar S, Khubber S, Reyaldeen R, et al. Advances in imaging and targeted therapies for recurrent pericarditis: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022 Sep 1;7(9):975-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35976625?tool=bestpractice.com

These therapies should be used in consultation with a rheumatologist.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015 Oct 13;314(14):1498-506.

https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1576078#.XAFHbdv7S70

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26461998?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Galluzzo A, Imazio M. Advances in medical therapy for pericardial diseases. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018 Sep;16(9):635-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30103638?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Vianello F, Cinetto F, Cavraro M, et al. Azathioprine in isolated recurrent pericarditis: a single centre experience. Int J Cardiol. 2011 Mar 17;147(3):477-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21296434?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Imazio M, Lazaros G, Picardi E, et al. Intravenous human immunoglobulins for refractory recurrent pericarditis: a systematic review of all published cases. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2016 Apr;17(4):263-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26090917?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Emmi G, Urban ML, Imazio M, et al. Use of interleukin-1 blockers in pericardial and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018 Jun 14;20(8):61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29904899?tool=bestpractice.com

[72]Brucato A, Imazio M, Gattorno M, et al. Effect of anakinra on recurrent pericarditis among patients with colchicine resistance and corticosteroid dependence: The AIRTRIP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016 Nov 8;316(18):1906-12.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2579869

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27825009?tool=bestpractice.com

Further studies are needed.

For patients with persistent, symptomatic recurrence refractory to all medical treatment, pericardiotomy is recommended.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

In tuberculous pericarditis, patients in whom there are recurrent effusions or evidence of constrictive physiology despite medical therapy, are treated surgically with pericardiectomy.[3]Imazio M, Brucato A, Mayosi BM, et al. Medical therapy of pericardial diseases: part I: idiopathic and infectious pericarditis. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010 Oct;11(10):712-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20736783?tool=bestpractice.com

It is particularly recommended if the patient’s condition is not improving or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy. Standard antituberculosis drugs for 6 months is recommended for the prevention of tuberculous pericardial constriction.[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

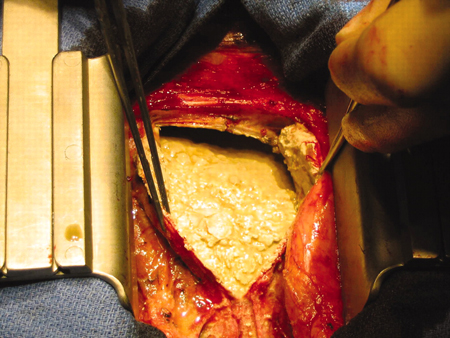

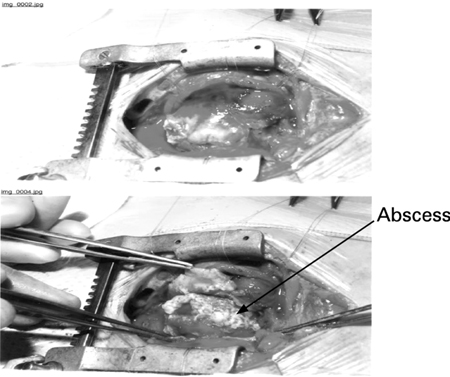

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pericardectomy in a 56-year-old male patient with idiopathic calcific constrictive pericarditis. The pericardium is thickened and calcifiedPatanwala I, Crilley J, Trewby PN. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0015 [Citation ends].

Pericardiectomy may also be necessary for treatment of recurrent nontuberculous pericarditis refractory to standard therapies, where constriction is present (e.g., following cardiac surgery or radiation therapy, or idiopathic constrictive pericarditis).[42]Kumar S, Khubber S, Reyaldeen R, et al. Advances in imaging and targeted therapies for recurrent pericarditis: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022 Sep 1;7(9):975-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35976625?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Tzani A, Doulamis IP, Tzoumas A, et al. Meta-analysis of population characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2021 May 1;146:120-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33539860?tool=bestpractice.com

Exercise should be restricted until chest pain resolves and inflammatory markers have normalized.[55]Kim JH, Baggish AL, Levine BD, et al. Clinical considerations for competitive sports participation for athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2025 Feb 20 [Epub ahead of print].

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001297

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39973614?tool=bestpractice.com

A minimum of 3 months is often considered appropriate (and recommended for patients involved in competitive sports), but shorter periods of exercise restriction may be considered depending on patient and disease characteristics (e.g., nonathletes and/or mild clinical picture).[1]Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2921-64.

http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/36/42/2921.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26320112?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28;113(12):1622-32.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/113/12/1622

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16567581?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, et al. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177006?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Pelliccia A, Solberg EE, Papadakis M, et al. Recommendations for participation in competitive and leisure time sport in athletes with cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, and pericarditis: position statement of the Sport Cardiology Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J. 2019 Jan 1;40(1):19-33.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/40/1/19/5248228

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30561613?tool=bestpractice.com

]

Pericardiectomy is recommended if the patient does not improve or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy.[1][67] Most patients with uremic pericarditis respond to intensive dialysis within 1 to 2 weeks. Autoimmune disorders are treated with corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive therapies depending on the specific condition. Treatment of neoplasms may involve any combination of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery, depending on the type of tumor identified.[37][38] Patients with viral pericarditis may benefit from specific antiviral therapy; however, an infectious disease attending should be involved.

]

Pericardiectomy is recommended if the patient does not improve or is deteriorating after 4 to 8 weeks of antituberculosis therapy.[1][67] Most patients with uremic pericarditis respond to intensive dialysis within 1 to 2 weeks. Autoimmune disorders are treated with corticosteroids and/or other immunosuppressive therapies depending on the specific condition. Treatment of neoplasms may involve any combination of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or surgery, depending on the type of tumor identified.[37][38] Patients with viral pericarditis may benefit from specific antiviral therapy; however, an infectious disease attending should be involved.