Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Acute pericarditis is a clinical diagnosis. Aspects of the clinical history and presentation, physical exam, and ECG need to be combined in order to make the diagnosis. The diagnosis is confirmed in the presence of at least 2 of the 4 clinical criteria:[16][20][36][37][38]

Typical chest pain

Pericardial friction rub

Widespread ST elevation

Pericardial effusion.

Because the most common causes of acute pericarditis usually follow a benign course, it is not essential to determine the etiology in all patients, particularly in regions where tuberculosis has a low prevalence.[1] In addition, there is a relatively low yield of diagnostic investigations. However, patients should be screened for high-risk features, and attempts to determine etiology are recommended so that specific causes associated with increased risk of complications can be identified.[1]

History

The key finding on history is constant, pleuritic central chest pain that is worse in the recumbent position and radiates to one or both trapezius ridges (phrenic nerves both innervate the pericardium and trapezius ridges).

The pain is sharp, stabbing, pleuritic, or aching, and can mimic the pain of myocardial ischemia or infarction, particularly when dull or pressure-like.

Trapezius ridge pain is more specific for pericardial pain. Almost all patients report relief of pain with sitting up or leaning forward.[39]

The pain is generally constant, not related to exertion, and poorly responsive to nitrates.[13][15]

The presence of associated high or spiking fever suggests an infectious cause.

Key risk factors include:[2][3]

Male sex

Age 20 to 50 years

Transmural myocardial infarction (MI)

Cardiac surgery

Neoplasm

Viral and bacterial infection (e.g., Coxsackie virus A9 or B1-4, Echo 8, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella, rubella, HIV, Parvo-19, SARS-CoV-2, tuberculosis)

Uremia

Dialysis treatment

Systemic autoimmune disorders.

A history of other underlying causes may also be present including radiation therapy, cardiac surgery, percutaneous cardiac interventions, and neoplasms.

Bacterial pericarditis is a relatively rare entity in the antibiotic era. It is characterized by an acute illness with high fever, tachycardia, and cough. Pleuritic or nonpleuritic chest pain is present in a minority of patients. Patients with postoperative bacterial pericarditis have signs of sternal wound infection or mediastinitis. The diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.

Physical exam

The presence of a pericardial friction rub on physical exam is a key finding that supports the diagnosis.[39] It is heard best at the left lower sternal border and at the cardiac borders. The presence of a rub is 100% specific, but it is often absent at initial presentation (rub may be present in less than 33% of cases).[1] The rub can come and go over hours, so the sensitivity is based upon the frequency of cardiac auscultation and it is important to examine patients with suspected pericarditis repeatedly.[14]

Constrictive pericarditis should be suspected in a patient with unexplained right heart failure in whom there is a history of pericardial disease or predisposing pericardial injury even if the pericardial insult predates the clinical presentation by years.[40] Symptoms and signs of right-sided heart failure include fatigue, ankle edema, and, in severe cases, ascites.

Initial workup

Although diagnosis is essentially clinical, some tests are indicated.[3][13][15][38]

ECG

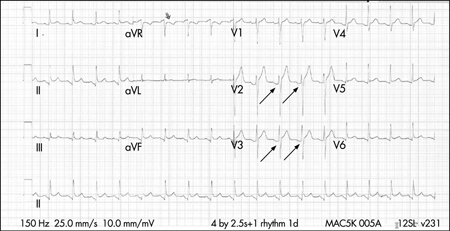

An ECG is very important in the initial round of tests for all patients. Typical ECG changes have been reported to occur in up to 60% of cases.[1] The classic ECG changes are global upwardly concave ST-segment (J-point) elevations with PR segment depressions in most leads with J-point depression and PR elevation in leads aVR and V1. If the patient is seen soon after symptom onset, PR depressions may be noted prior to ST elevation. The ECG may evolve over 4 phases: stage 1 consists of ST elevation and upright T-waves that may resolve to normal (stage 2) over a period of several days or evolves further to T-wave inversion (stage 3) and then to normal (stage 4). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG in a patient with acute pericarditis, showing diffuse ST-segment elevation in the precordial leads. There is also PR-segment depression in leads V2-V6 (arrows)Rathore S, Dodds PA. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2006.097071 [Citation ends].

Laboratory tests

Blood tests performed in the initial workup are:

CBC: blood count does not provide definitive insight into the cause or management strategy. Leukocytosis with a marked shift to the left may be seen with purulent pericarditis or other infectious etiology.[15] Indicated before commencing colchicine therapy, which may cause neutropenia and bone marrow suppression.

BUN: elevated levels of BUN (particularly >60 mg/dL) suggest a uremic cause.[15]

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): elevated ESR is consistent with an inflammatory state.[15]

C-reactive protein: elevated C-reactive protein is common and consistent with an inflammatory state; serial measurement may be helpful for monitoring the activity of the disease and efficacy of therapy.[1][15]

Initial and serial serum troponins: elevated levels may be present and may reflect myocardial involvement (e.g., myopericarditis), but the test is not specific or sensitive.[12][15] Plasma troponins are elevated in 35% to 50% of patients with pericarditis. The magnitude of elevation correlates with the extent of ST-segment elevation and can be in the range considered diagnostic of acute MI in some patients. Levels return to normal within 1 to 2 weeks of diagnosis (often within days). Elevated levels do not appear to confer prognostic significance.

Other investigations

Although rare, purulent pericarditis is immediately life-threatening and requires immediate confirmation of diagnosis via urgent pericardiocentesis. Pericardial fluid should be tested for bacterial, fungal, and tuberculous causes, and blood should be drawn for culture.

A chest x-ray is ordered in all patients but is often normal unless there is an associated large pericardial effusion, in which a water bottle-shaped enlarged cardiac silhouette is seen. The chest x-ray may also demonstrate concomitant lung pathology providing evidence of tuberculosis, fungal disease, pneumonia, or a neoplasm that may be related to the disease.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

How to record an ECG. Demonstrates placement of chest and limb electrodes.

Follow-up tests

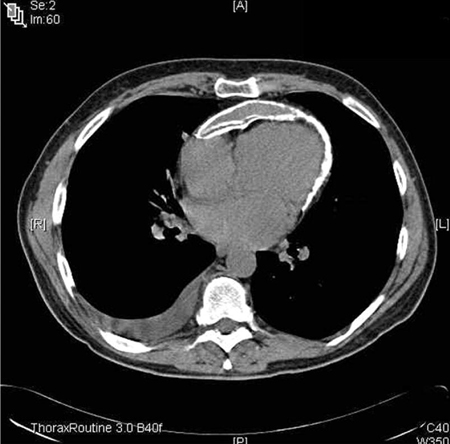

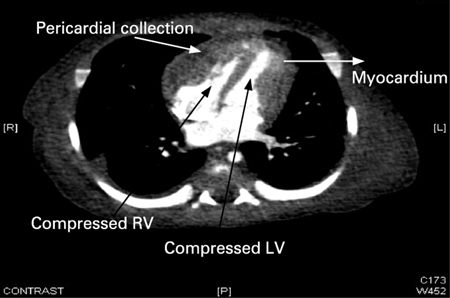

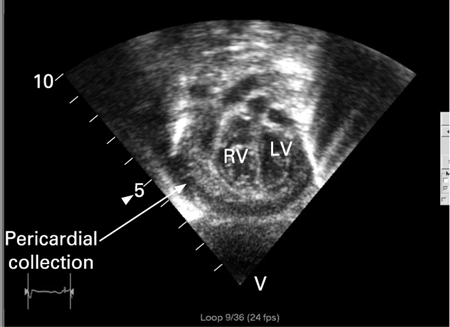

Other imaging modalities have limited usefulness in uncomplicated acute pericarditis, but are important in assessing complications.[13][15] Echocardiography is indicated especially when cardiac tamponade is suspected. It can also help differentiate pericarditis from acute coronary syndromes; global ST elevations in the absence of left ventricular (LV) wall motion abnormalities and a trivial pericardial effusion support the diagnosis of acute pericarditis. Echocardiography is insensitive to pericardial inflammation in dry pericarditis but is important in detecting pericardial effusions. Chest computed tomography and increasingly, magnetic resonance imaging, may be used to help diagnose constrictive pericarditis or pericardial effusion.[18][42]

If tuberculous pericarditis is suspected, diagnostic accuracy can be improved with identification of the organism from pericardial fluid or pericardial biopsy.[43][44][45] Adenosine deaminase activity within the pericardial effusion may also aid in the diagnosis as an adjunctive marker.[46]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT showing a double layer of pericardial calcification in a 56-year-old male patient with idiopathic calcific constrictive pericarditisPatanwala I, Crilley J, Trewby PN. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0015 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT in a baby with purulent pericarditis showing a pericardial collection with compression of the left (LV) and right (RV) ventriclesKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT in a baby with purulent pericarditis showing a pericardial collection with compression of the left (LV) and right (RV) ventriclesKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiogram in a baby with purulent pericarditis, showing a pericardial collection. LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricleKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Echocardiogram in a baby with purulent pericarditis, showing a pericardial collection. LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricleKaruppaswamy V, Shauq A, Alphonso N. BMJ Case Reports 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.2007.136564 [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer