All patients with bacteremia should be suspected of potentially having IE, particularly those with an audible murmur. The classic new or worsening cardiac murmur is rare. Patients who develop new regurgitant murmurs are at increased risk of developing congestive heart failure. Elderly or immunocompromised patients may present atypically, without fever. As the population ages, IE is becoming more frequent in patients ages over 70 years, with trends toward worsening outcomes.[61]Selton-Suty C, Hoen B, Grentzinger A, et al. Clinical and bacteriological characteristics of infective endocarditis in the elderly. Heart. 1997 Mar;77(3):260-3.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC484694

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9093046?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnosis in older people is often made later in the course of the disease as a result of more indolent presentations, and this undoubtedly contributes to poorer outcomes. While it is uncommon in pregnancy, IE should be considered in pregnant patients who present with fever accompanied by cardiac signs, including tachycardia, new or changing heart murmurs and evidence of septic emboli.[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Onofrei VA, Adam CA, Marcu DTM, et al. Infective endocarditis during pregnancy-keep it safe and simple!. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 May 12;59(5):939.

https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/59/5/939

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37241171?tool=bestpractice.com

The same risk factors for IE pertain to pregnant patients as nonpregnant patients.[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Onofrei VA, Adam CA, Marcu DTM, et al. Infective endocarditis during pregnancy-keep it safe and simple!. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 May 12;59(5):939.

https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/59/5/939

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37241171?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial laboratory studies should include basic complete blood count (CBC) and electrolyte panel, at least two sets of blood cultures (ideally taken >6 hours apart if clinical status allows), and urinalysis. Blood cultures are recommended to be taken prior to initiation of antibiotics.[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

All patients should have an initial ECG, and subsequently an echocardiogram must be obtained.[6]Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/15/1435.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373316?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, et al. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010 Mar;11(2):202-19.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20223755?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Xie P, Zhuang X, Liu M, et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis-the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):92.

https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33478412?tool=bestpractice.com

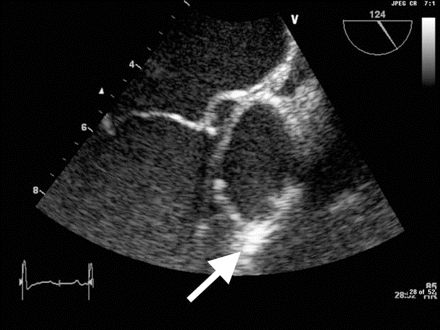

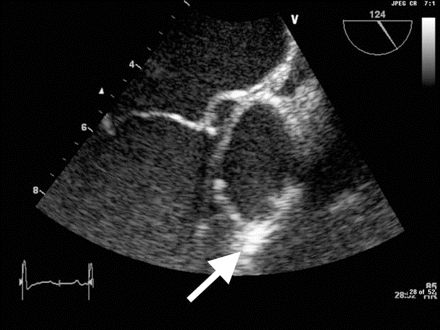

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A transthoracic echo showing large mobile vegetations on the anterior and posterior leaflets of the tricuspid valveFoley JA, Augustine D, Bond R, et al. Lost without Occam's razor: Escherichia coli tricuspid valve endocarditis in a non-intravenous drug user. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Aug 10;2010. pii: bcr0220102769 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Image from transesophageal echocardiogram. White arrow indicates vegetation on the patient's aortic valveTeoh LS, Hart HH, Soh MC, et al. Bartonella henselae aortic valve endocarditis mimicking systemic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Oct 21;2010. pii: bcr0420102945 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Image from transesophageal echocardiogram. White arrow indicates vegetation on the patient's aortic valveTeoh LS, Hart HH, Soh MC, et al. Bartonella henselae aortic valve endocarditis mimicking systemic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Oct 21;2010. pii: bcr0420102945 [Citation ends].

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommend using the Modified Duke Criteria in patients with suspected IE.[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

[

Endocarditis Diagnostic Criteria - Modified Duke Criteria

Opens in new window

]

Acute

Patients often present with signs and symptoms of peripheral or central emboli, or with evidence of decompensated congestive heart failure. Therefore, urgent evaluation for IE is important for any patients who present with fever in conjunction with headache, meningeal signs, stroke symptoms, chest pain, dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea; and for any patients with unexplained fever who are at high risk of IE (e.g., congenital or acquired valvular disease, previous IE, prosthetic heart valves, congenital or heritable heart malformations, immunodeficiency, injection drug use).[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Arthralgias and back pain may also result from peripheral septic emboli. Classic immunologic features (e.g., Osler nodes, Roth spots) are uncommon, due to rapid onset of disease process.

Subacute

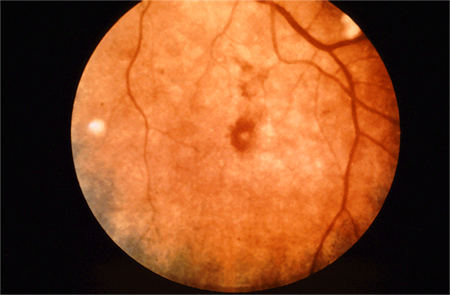

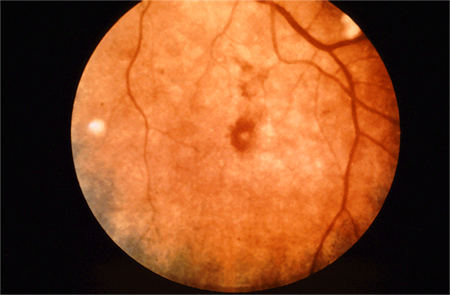

Patients present with fever and chills, nonspecific constitutional symptoms (night sweats, malaise, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, myalgias), or palpitations. Physical exam is often nonspecific, but subacute presentations are more likely to exhibit classic exam findings such as Janeway lesions (hemorrhagic, macular, painless plaques with a predilection for the palms and soles), Osler nodes (small, painful, nodular lesions usually found on the pads of the fingers or toes) splinter hemorrhages (commonly noted in the nails of the upper and lower extremities), or cutaneous infarcts. Palatal petechiae may also be present. Fundoscopy may detect Roth spots (oval, pale, retinal lesions surrounded by hemorrhage). Skin exam should include assessment for evidence of intravenous drug use. Subacute IE must always be in the differential diagnosis of a patient with progressive fever and constitutional symptoms.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler's nodesFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler's nodesFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cutaneous infarctsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cutaneous infarctsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

IE in the intensive care unit (ICU)

There are multiple challenges to diagnosing IE in the ICU. Presentation is often atypical, and may be concealed by other pathology. Furthermore, transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is likely to be less diagnostically accurate, owing to the practical difficulties of scanning in the ICU. Hence, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) must be considered at an earlier stage in the diagnostic process.

Laboratory tests

Blood cultures are the most important laboratory test for confirming IE. At least three sets of blood cultures from different venipuncture sites should be taken, the first and last samples taken at least one hour apart (ideally >6 hours apart if clinical status allows).[6]Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/15/1435.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373316?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

Blood culture results taken this way are positive in 90% of patients with IE.[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Cultures should not be taken from indwelling lines, to minimize risk of contamination.

However, empiric antibiotic therapy should not be delayed while waiting to take three sets of blood cultures if the patient is unwell (e.g., with sepsis).[64]Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021 Nov 1;49(11):e1063-143.

https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/fulltext/2021/11000/surviving_sepsis_campaign__international.21.aspx

The volume of blood sent for culture is more important than the number of sets of cultures.[65]Lamy B, Dargère S, Arendrup MC, et al. How to optimize the use of blood cultures for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? a state-of-the art. Front Microbiol. 2016 May 12:7:697.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00697/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27242721?tool=bestpractice.com

The most common cause of culture-negative endocarditis is antibiotic therapy preceding blood cultures.[66]Habib G, Derumeaux G, Avierinos JF, et al. Value and limitations of the Duke criteria in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 Jun;33(7):2023-9.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109799001163?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10362209?tool=bestpractice.com

Do not routinely request extended incubation of blood cultures in suspected endocarditis.[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

[67]American Society for Microbiology. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2022 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230320213810/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/the-american-society-for-microbiology

Other initial laboratory studies should include basic CBC and electrolyte panel, C-reactive protein (CRP), and urinalysis. If the patient is febrile, laboratory signs of infection (such as elevated CRP or leukocytosis), anemia, and microscopic hematuria support a diagnosis of IE. However, these are not specific for the diagnosis of IE.

In practice, CRP is also useful as a baseline test and to monitor response to treatment. Elevated CRP >40 mg/L is an independent risk factor for embolic events in patients with IE.[68]Hu W, Wang X, Su G. Infective endocarditis complicated by embolic events: pathogenesis and predictors. Clin Cardiol. 2021 Mar;44(3):307-15.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/clc.23554

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33527443?tool=bestpractice.com

Testing for rheumatoid factor and measuring erythrocyte sedimentation rate and complement levels may also be helpful. Urinalysis is used to evaluate renal involvement. In addition, electrolyte panel, glucose, and liver function tests are used to mark progress of the disease, and to assess vital organ function and systemic effects of infection.

Emerging tests

Mean platelet volume (MPV) is associated with platelet activation which occurs in the setting of endothelial damage. Increased MPV has been shown to be an independent predictor of embolic events in patients with IE.

Anti‐beta-2‐glycoprotein I antibodies enhance activation of platelets and the coagulation cascade and have been associated with increased risk of embolic events.

D-dimer and troponin I have also been linked to increased embolic risk but are nonspecific and may be surrogate markers for severity of illness rather than independent predictors of embolic events.[68]Hu W, Wang X, Su G. Infective endocarditis complicated by embolic events: pathogenesis and predictors. Clin Cardiol. 2021 Mar;44(3):307-15.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/clc.23554

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33527443?tool=bestpractice.com

Echocardiography

Echocardiography should be performed in all patients with suspected IE.[6]Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/15/1435.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373316?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, et al. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010 Mar;11(2):202-19.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20223755?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Xie P, Zhuang X, Liu M, et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis-the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):92.

https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33478412?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: infective endocarditis. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69408/Narrative

Echocardiography is important not only for confirming or ruling out the diagnosis but also for evaluation of complications and prognosis.[62]Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, et al. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010 Mar;11(2):202-19.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20223755?tool=bestpractice.com

The decision to obtain a TTE rather than TEE is often difficult and has been considered by various guidelines.[6]Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/15/1435.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373316?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Habib G, Badano L, Tribouilloy C, et al. Recommendations for the practice of echocardiography in infective endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010 Mar;11(2):202-19.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20223755?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Xie P, Zhuang X, Liu M, et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis-the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):92.

https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33478412?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: infective endocarditis. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69408/Narrative

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommend that any patient suspected of having native valve IE should be screened with TTE to evaluate for the presence of a vegetation, and to assess any effects on valvular function.[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

If negative, and suspicion still remains, patients should undergo TEE.[15]Miró JM, del Río A, Mestres CA. Infective endocarditis and cardiac surgery in intravenous drug abusers and HIV-1 infected patients. Cardiol Clin. 2003 May;21(2):167-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12874891?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Xie P, Zhuang X, Liu M, et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis-the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):92.

https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33478412?tool=bestpractice.com

TEE is the preferred form of echocardiography in people with prosthetic material suspected to have IE.[15]Miró JM, del Río A, Mestres CA. Infective endocarditis and cardiac surgery in intravenous drug abusers and HIV-1 infected patients. Cardiol Clin. 2003 May;21(2):167-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12874891?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Xie P, Zhuang X, Liu M, et al. An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate use of echocardiography for adult infective endocarditis-the timing and mode of assessment (TTE or TEE). BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Jan 21;21(1):92.

https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-021-05785-6

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33478412?tool=bestpractice.com

TEE is also indicated in patients with a positive TTE, but where complications are suspected or likely, and before cardiac surgery during active IE. 3-dimensional echocardiography can provide additional anatomic information and may be used in concert with traditional 2-dimensional echocardiography.[70]Galzerano D, Kinsara AJ, Di Michele S, et al. Three dimensional transesophageal echocardiography: a missing link in infective endocarditis imaging? Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Mar;36(3):403-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31902093?tool=bestpractice.com

When TEE is contraindicated or not feasible, intracardiac echocardiography may be an alternative for diagnosing IE.[71]Sanchez-Nadales A, Cedeño J, Sonnino A, et al. Utility of intracardiac echocardiography for infective endocarditis and cardiovascular device-related endocarditis: a contemporary systematic review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023 Sep;48(9):101791.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37172870?tool=bestpractice.com

ECG

An ECG should be undertaken, as progression of the infection may lead to conduction system disease.[72]Porter TR, Airey K, Quader M. Mitral valve endocarditis presenting as complete heart block. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33(1):100-1.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1413594

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16572886?tool=bestpractice.com

Conduction abnormalities secondary to IE (mainly first-, second-, and third-degree atrioventricular block) are uncommon but are associated with worse prognosis and higher mortality compared with patients without conduction abnormalities.[73]DiNubile MJ, Calderwood SB, Steinhaus DM, et al. Cardiac conduction abnormalities complicating native valve active infective endocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1986 Dec 1;58(13):1213-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3788810?tool=bestpractice.com

Cardiac computed tomography (CT)

CT imaging is used for the diagnosis of native and prosthetic valve IE and for detection of complications of IE, including abscesses, pseudoaneurysms, and fistulae.[74]Jain V, Wang TKM, Bansal A, et al. Diagnostic performance of cardiac computed tomography versus transesophageal echocardiography in infective endocarditis: a contemporary comparative meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2021 Jul-Aug;15(4):313-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33281097?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]Expert Panel on Cardiac Imaging, Malik SB, Hsu JY, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5s):S52-61.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00029-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958118?tool=bestpractice.com

CT has been found to compare favorably with TTE in detecting valvular abnormalities in patients with IE, but it may miss small defects (e.g., small leaflet perforations [≤2 mm diameter], small vegetations <10 mm).[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Feuchtner GM, Stolzmann P, Dichtl W, et al. Multislice computed tomography in infective endocarditis: comparison with transesophageal echocardiography and intraoperative findings. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Feb 3;53(5):436-44.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109708036668?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19179202?tool=bestpractice.com

Whole-body and brain CT can be used to look for distant lesions, systemic complications of IE, and septic emboli, as well as having a role in detecting extracardiac sources of bacteremia and potentially alternate diagnoses in patients where IE has been excluded.[6]Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/15/1435.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373316?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

CT angiography is a sensitive and specific test for detecting mycotic arterial aneurysms; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior for assessment of neurologic complications in terms of imaging, but is limited by accessibility and availability.[6]Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 Oct 13;132(15):1435-86.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/132/15/1435.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26373316?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

Head MRI

MRI is of less diagnostic value than CT, but is the imaging modality of choice when investigating the cerebral complications of IE, with studies consistently reporting cerebral infarcts in up to 80% of patients.[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

[77]Snygg-Martin U, Gustafsson L, Rosengren L, et al. Cerebrovascular complications in patients with left-sided infective endocarditis are common: a prospective study using magnetic resonance imaging and neurochemical brain damage markers. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jul 1;47(1):23-30.

http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/47/1/23.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18491965?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]Ahn Y, Joo L, Suh CH, et al. Impact of brain MRI on the diagnosis of infective endocarditis and treatment decisions: systematic review and meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2022 Jun;218(6):958-68.

https://www.ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.21.26896

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35043667?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI reveals cerebral lesions in 50% of patients who do not demonstrate neurologic symptoms.[79]Hess A, Klein I, Iung B, et al. Brain MRI findings in neurologically asymptomatic patients with infective endocarditis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013 Aug;34(8):1579-84.

http://www.ajnr.org/content/34/8/1579.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23639563?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI is also used to assess spinal involvement in IE, including spondylodiscitis and vertebral osteomyelitis.[7]Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Oct 14;44(39):3948-4042.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/44/39/3948/7243107

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37622656?tool=bestpractice.com

Nuclear imaging and photon emission tomography (PET)

Single-PET/CT and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT may be particularly useful in patients with “possible IE” defined according to Duke criteria, in the demonstration of infectious embolic events, and in cases of suspected prosthetic valve IE where echocardiography is not diagnostic.[20]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

[75]Expert Panel on Cardiac Imaging, Malik SB, Hsu JY, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 May;18(5s):S52-61.

https://www.jacr.org/article/S1546-1440(21)00029-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33958118?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Saby L, Laas O, Habib G, et al. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis: increased valvular 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake as a novel major criterion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jun 11;61(23):2374-82.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23583251?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]O'Gorman P, Nair L, Kisiel N, et al. Meta-analysis assessing the sensitivity and specificity of (18)F-FDG PET/CT for the diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) using individual patient data (IPD). Am Heart J. 2023 Jul;261:21-34.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36934977?tool=bestpractice.com

[82]Mahmood M, Kendi AT, Ajmal S, et al. Meta-analysis of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019 Jun;26(3):922-35.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29086386?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]Wang TKM, Sánchez-Nadales A, Igbinomwanhia E, et al. Diagnosis of infective endocarditis by subtype using (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: a contemporary meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020 Jun;13(6):e010600.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.010600

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32507019?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Bourque JM, Birgersdotter-Green U, Bravo PE, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT and radiolabeled leukocyte SPECT/CT imaging for the evaluation of cardiovascular infection in the multimodality context: ASNC imaging indications (ASNC I2) Series Expert Consensus recommendations from ASNC, AATS, ACC, AHA, ASE, EANM, HRS, IDSA, SCCT, SNMMI, and STS. Clin Infect Dis. 11 Mar 2024 [Epub ahead of print].

https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciae046/7618607?login=false

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38466039?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Image from transesophageal echocardiogram. White arrow indicates vegetation on the patient's aortic valveTeoh LS, Hart HH, Soh MC, et al. Bartonella henselae aortic valve endocarditis mimicking systemic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Oct 21;2010. pii: bcr0420102945 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Image from transesophageal echocardiogram. White arrow indicates vegetation on the patient's aortic valveTeoh LS, Hart HH, Soh MC, et al. Bartonella henselae aortic valve endocarditis mimicking systemic vasculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2010 Oct 21;2010. pii: bcr0420102945 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler's nodesFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler's nodesFrom a private collection; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cutaneous infarctsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cutaneous infarctsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].