Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) symptoms and signs are nonspecific, and diagnosis is based on clinicopathologic features. Clinically, there must be symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. Histologically, there must be an esophageal epithelial infiltrate of ≥15 eosinophils per high-power microscopy field (eos/hpf).[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007 Oct;133(4):1342-63.

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(07)01474-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919504?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23567357?tool=bestpractice.com

To account for variations in the area considered within a high-power field and the increasing use of digital optical microscopy, UK guidelines recommend using an updated peak eosinophil count of ≥15 per 0.3 mm².[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

Competing causes of esophageal eosinophilia must be excluded prior to confirming the diagnosis; a finding of increased eosinophils alone on biopsy is not itself diagnostic. While there are unusual causes of esophageal eosinophilia (such as esophageal Crohn disease, connective tissue or autoimmune disorders, hypereosinophilic syndrome, a more diffuse eosinophilic gastroenteritis, parasitic infections, drug reactions, pill esophagitis, and graft versus host disease affecting the esophagus) these can usually be excluded by the history, physical examination, and standard blood tests. From a practical standpoint, the most common condition to evaluate for as contributing to esophageal eosinophilia is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[80]Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct;155(4):1022-33.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)34763-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30009819?tool=bestpractice.com

History

EoE has been reported in patients of all ages, but is more commonly seen in children and young adults, with the peak prevalence occurring between ages 30 years and 40 years.[26]Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Apr;12(4):589-96.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(13)01304-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24035773?tool=bestpractice.com

Approximately two-thirds of patients are male, although the reasons for this are unknown.[27]Lynch KL, Dhalla S, Chedid V, et al. Gender is a determinative factor in the initial clinical presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2016 Feb-Mar;29(2):174-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25626069?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014 Dec;147(6):1238-54.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(14)00980-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25109885?tool=bestpractice.com

Family history of EoE may be present.[77]Alexander ES, Martin LJ, Collins MH, et al. Twin and family studies reveal strong environmental and weaker genetic cues explaining heritability of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Nov;134(5):1084-92.

https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(14)01009-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25258143?tool=bestpractice.com

Up to 80% of children and 60% of adults have been reported to have concomitant allergic conditions (e.g., asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis/sinusitis, or food allergies).[31]Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):30-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19172120?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Simon D, Marti H, Heer P, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis is frequently associated with IgE-mediated allergic airway diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 May;115(5):1090-2.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(05)00128-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15867873?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic characteristics of adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 May;6(5):531-5.

http://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(07)01248-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18304887?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Penfield JD, Lang DM, Goldblum JR, et al. The role of allergy evaluation in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010 Jan;44(1):22-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19564792?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Dec;7(12):1305-13.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(09)00834-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19733260?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Assa'ad AH, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: an 8-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 Mar;119(3):731-8.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(06)03792-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17258309?tool=bestpractice.com

In adolescents and adults, dysphagia is the hallmark feature.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007 Oct;133(4):1342-63.

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(07)01474-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919504?tool=bestpractice.com

[28]Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in clinical management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014 Dec;147(6):1238-54.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(14)00980-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25109885?tool=bestpractice.com

It is often a long-standing symptom, and severity can range from food going down slowly, to transiently sticking, to sticking for a longer period of time requiring regurgitation, to frank food bolus impaction requiring urgent endoscopy to clear the bolus.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

[13]Sperry SL, Crockett SD, Miller CB, et al. Esophageal foreign-body impactions: epidemiology, time trends, and the impact of the increasing prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Nov;74(5):985-91.

https://www.giejournal.org/article/S0016-5107(11)01911-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21889135?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Kerlin P, Jones D, Remedios M, et al. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults with food bolus obstruction of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007 Apr;41(4):356-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17413601?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, et al. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005 Jun;61(7):795-801.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15933677?tool=bestpractice.com

When taking the history, it is not enough to simply ask if the patient has trouble swallowing. Many patients have coped with symptoms for years, have modified their eating to chew thoroughly, eat slowly, drink copious liquids, lubricate foods, or avoid foods that tend to get stuck. They may also not go out to eat for fear of having an episode of food sticking in public. These avoidance and modification behaviors minimize symptoms, and should be asked about specifically. In addition to dysphagia, patients may report heartburn (which can mimic symptoms of GERD) and chest discomfort.

In children, symptoms are nonspecific. Infants may have failure to thrive, feeding intolerance, crying/irritability, and vomiting. Older children may report abdominal pain, heartburn (again, mimicking GERD), regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, or food avoidance.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007 Oct;133(4):1342-63.

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(07)01474-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919504?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23567357?tool=bestpractice.com

It may be unclear whether some of these symptoms (e.g., chest pain or vomiting) represent dysphagia or transient food impactions as younger children are not able to fully describe the sensation they are experiencing. UK guidelines recommend considering a diagnosis of EoE in all adult patients with dysphagia or food bolus obstruction and in children of all ages whose symptoms are consistent with their age.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

Children under 6 are more likely to present with feeding difficulties, while older children present with abdominal pain, dysphagia, or food impaction.[31]Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):30-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19172120?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

There are no specific findings on examination to suggest a diagnosis of EoE. However, the patient should be assessed for other potential conditions in the differential diagnosis, for example, evidence of atopy (e.g., wheezing due to asthma, eczema, or hives on the skin), uncontrolled acid reflux (e.g., dental erosion), connective tissue disorders (e.g., joint hyperflexibility, arthritis, skin tightening), signs of malnutrition, or other unexpected findings.

Initial investigations

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy is required to document increased esophageal eosinophilia necessary to diagnose the condition. It should be ordered in all patients with suspected EoE. There are a number of characteristic endoscopic signs of EoE. While these are nonspecific (and not formally part of the diagnostic criteria), they can be highly suggestive of EoE.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007 Oct;133(4):1342-63.

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(07)01474-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919504?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23567357?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnostic endoscopy should be performed on patients receiving no treatment (or when a proton pump inhibitor has been discontinued for 3-4 weeks, if possible).[81]Odiase E, Schwartz A, Souza RF, et al. New eosinophilic esophagitis concepts call for change in proton pump inhibitor management before diagnostic endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2018 Apr;154(5):1217-21.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(18)30255-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29510130?tool=bestpractice.com

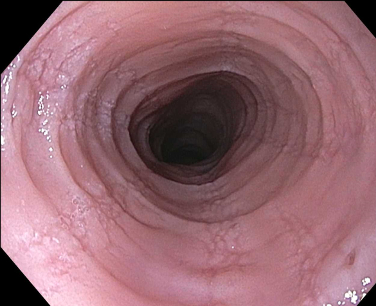

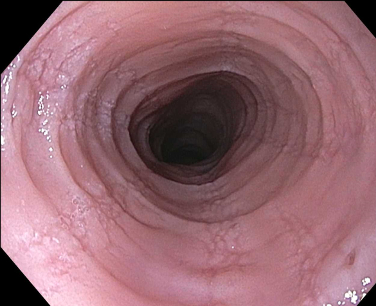

Endoscopic signs include:

Fixed esophageal rings

Focal esophageal strictures

Diffuse esophageal narrowing

Edema or congestion of the mucosa with loss of normal vascular markings

Linear furrows

White plaques or exudates (which correlate with the histologic finding of eosinophilic microabscesses)

Crêpe-paper mucosa (a sign of mucosa fragility where the esophageal mucosa tears from insufflation or passage of the scope).

These findings can be formally graded with the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS), which accounts for the five most typical EoE endoscopic features (and also form the acronym): edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures.[82]Dellon ES, Cotton CC, Gebhart JH, et al. Accuracy of the eosinophilic esophagitis endoscopic reference score in diagnosis and determining response to treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jan;14(1):31-9.

https://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(15)01302-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26404868?tool=bestpractice.com

It is important to note that these findings are not required for the diagnosis of EoE. Endoscopy can appear normal in a number of patients (most commonly children), and biopsies should still be taken if this is the case.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

After the esophagus is assessed visually, biopsies are obtained. Recommendations on how many biopsies should be taken vary from at least 2-4 in the US, to at least 6 in Europe, with 6 considered the gold standard.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias Á, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017 Apr;5(3):335-58.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5415218

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28507746?tool=bestpractice.com

Eosinophilic infiltrate in EoE is patchy, and an increasing number of biopsies maximizes diagnostic sensitivity.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23567357?tool=bestpractice.com

[84]Collins MH. Histopathologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis and eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014 Jun;43(2):257-68.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24813514?tool=bestpractice.com

[85]Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Distribution and variability of esophageal eosinophilia in patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Mod Pathol. 2015 Mar;28(3):383-90.

https://mp.uscap.org/article/S0893-3952(22)01908-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25216228?tool=bestpractice.com

[86]Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, et al. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 Sep;64(3):313-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16923475?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Nielsen JA, Lager DJ, Lewin M, et al. The optimal number of biopsy fragments to establish a morphologic diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr;109(4):515-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24445569?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]Saffari H, Peterson KA, Fang JC, et al. Patchy eosinophil distributions in an esophagectomy specimen from a patient with eosinophilic esophagitis: Implications for endoscopic biopsy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Sep;130(3):798-800.

https://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(12)00446-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22502795?tool=bestpractice.com

If a patient presents with food bolus obstruction, sufficient biopsies should be taken at the time of endoscopy to ensure a diagnosis of EoE is not missed - if the obstruction has spontaneously cleared or insufficient diagnostic biopsies have been obtained at the index endoscopy, elective endoscopy should be arranged before discharge.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

Recommendations in the UK also specify that biopsies be taken from targeted (visibly abnormal) and non-targeted areas.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

On histologic examination of the biopsy specimens, the convention is to quantify the peak eosinophil count in the most inflamed area of the esophageal epithelium. Eosinophils are quantified per high-power microscopy field, and the count (eos/hpf) is reported. A count of ≥15 eos/hpf is required to diagnose EoE.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007 Oct;133(4):1342-63.

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(07)01474-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17919504?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23567357?tool=bestpractice.com

The standard size of a high-power field is 0.3 mm². To account for variation in the area considered to be a high-power field and the increasing use of digital optical microscopy, UK guidelines recommend using an updated peak eosinophil count of ≥15 per 0.3 mm².[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

There are also supporting histologic features including basal zone hypertrophy, lamina propria fibrosis, surface layering of eosinophils, eosinophil degranulation, and eosinophil microabscesses. These, and several other features, have been developed into an EoE Histologic Scoring System (HSS).[89]Collins MH, Martin LJ, Alexander ES, et al. Newly developed and validated eosinophilic esophagitis histology scoring system and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Dis Esophagus. 2017 Feb 1;30(3):1-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5373936

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26857345?tool=bestpractice.com

The UK guidelines recommend that concomitant histologic features be included in the histologic description, with the peak eosinophil count, to aid diagnosis of EoE.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

While the elevated eosinophil counts and the associated endoscopic and histologic findings are all suggestive of EoE, they are not specific, so the clinician must interpret the combined clinical and histologic presentation to determine whether EoE is the correct diagnosis.

A complete blood count (with differential) should be considered in all patients to assess for peripheral eosinophilia, which is only rarely seen with EoE, and suggests that the patient should be evaluated for other systemic causes. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Esophageal biopsy showing a diffuse eosinophilic epithelial infiltrate as well as basal cell hyperplasia and spongiosisFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including esophageal rings, linear furrows, edema, mild white plaques, and narrowingFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including esophageal rings, linear furrows, edema, mild white plaques, and narrowingFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including white plaques, linear furrows, and edemaFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including white plaques, linear furrows, and edemaFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends].

Emerging investigations

There are currently no noninvasive or minimally invasive techniques available in routine care, although they are being studied.[1]Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jul;128(1):3-20.

http://www.jacionline.org/article/S0091-6749(11)00373-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477849?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):679-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23567357?tool=bestpractice.com

Transnasal endoscopy

A less invasive method for sampling the esophagus. In two small studies, it has been well-tolerated with only topical anesthetic in both children and adults.[90]Philpott H, Nandurkar S, Royce SG, et al. Ultrathin unsedated transnasal gastroscopy in monitoring eosinophilic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Mar;31(3):590-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26426817?tool=bestpractice.com

[91]Friedlander JA, DeBoer EM, Soden JS, et al. Unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy for monitoring therapy in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Feb;83(2):299-306.

https://www.giejournal.org/article/S0016-5107(15)02498-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26142551?tool=bestpractice.com

It may have a role in monitoring disease activity after treatment.

Esophageal string test

A minimally invasive esophageal sampling technique where a capsule containing a string is swallowed, and the string that is attached to the capsule is held outside of the mouth. The capsule dissolves and the string remains in the esophagus where it absorbs inflammatory factors related to EoE. After 1 hour, the string is removed and sent to a specialized laboratory where the inflammatory factors can be measured. Initial studies have shown that these factors correlate extremely well with the same factors measured in esophageal biopsies, and further work indicates the esophageal string test may provide a safe and minimally invasive way of disease monitoring.[92]Furuta GT, Kagalwalla AF, Lee JJ, et al. The oesophageal string test: a novel, minimally invasive method measures mucosal inflammation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut. 2013 Oct;62(10):1395-405.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3786608

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22895393?tool=bestpractice.com

[93]Ackerman SJ, Kagalwalla AF, Hirano I, et al. One-hour esophageal string test: a nonendoscopic minimally invasive test that accurately detects disease activity in eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Oct;114(10):1614-25.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/Fulltext/2019/10000/One_Hour_Esophageal_String_Test__A_Nonendoscopic.12.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31567192?tool=bestpractice.com

Cytosponge

A minimally invasive esophageal sampling technique where a capsule containing a sphere-shaped cytology mesh (sponge) is swallowed, and an attached string retained outside of the mouth. After 5 minutes, the capsule dissolves, which releases the sponge, and the string is used to pull the sponge through the esophagus where it collects a tissue sample before it is removed from the mouth. This sample can then be assessed for levels of esophageal eosinophils in a standard pathology laboratory. A preliminary study showed excellent correlation between the eosinophil levels in the sponge sample and in matched endoscopic biopsy samples.[94]Katzka DA, Geno DM, Ravi A, et al. Accuracy, safety, and tolerability of tissue collection by Cytosponge vs endoscopy for evaluation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;13(1):77-83.

http://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)00933-1/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24997328?tool=bestpractice.com

Additional studies are ongoing and indicate that cytosponge is a safe, well tolerated and accurate way to assess histologic activity, but the findings need to be validated in larger studies.[95]Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Alexander JA, et al. Accuracy and safety of the cytosponge for assessing histologic activity in eosinophilic esophagitis: a two-center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Oct;112(10):1538-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28809387?tool=bestpractice.com

Esophageal physiological testing

Assessment of mucosal impedance, a proxy for esophageal barrier function and integrity, has promise for monitoring EoE. Several studies have shown that mucosal impedance is lower in EoE than in other esophageal conditions such as erosive and nonerosive reflux disease and achalasia, and that this low impedance is seen throughout the entire esophagus.[64]van Rhijn BD, Weijenborg PW, Verheij J, et al. Proton pump inhibitors partially restore mucosal integrity in patients with proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia but not eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Nov;12(11):1815-23.

http://www.cghjournal.org/article/S1542-3565(14)00392-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24657840?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Katzka DA, Ravi K, Geno DM, et al. Endoscopic mucosal impedance measurements correlate with eosinophilia and dilation of intercellular spaces in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jul;13(7):1242-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25592662?tool=bestpractice.com

[96]Ates F, Yuksel ES, Higginbotham T, et al. Mucosal impedance discriminates GERD from non-GERD conditions. Gastroenterology. 2015 Feb;148(2):334-43.

http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(14)01267-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25448923?tool=bestpractice.com

A minimally invasive approach to measurement of mucosal impedance is not currently available.

UK guidelines recommend esophageal physiological testing for patients with EoE who remain symptomatic even though they have received appropriate treatment, have no evidence of fibrostenotic disease at endoscopy and are in histologic remission.[4]Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults. Gut. 2022 Aug;71(8):1459-87.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/71/8/1459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35606089?tool=bestpractice.com

EoE diagnostic panel (EDP)

The EDP is a 94-gene expression panel that uses a single esophageal biopsy to yield a summary gene expression score. This score has been shown to discriminate EoE cases from non-EoE controls (including patients with GERD) with a high degree of accuracy.[61]Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan TM, et al. Molecular diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis by gene expression profiling. Gastroenterology. 2013 Dec;145(6):1289-99.

https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(13)01266-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23978633?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Dellon ES, Yellore V, Andreatta M, et al. A single biopsy is valid for genetic diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis regardless of tissue preservation or location in the esophagus. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015 Jun;24(2):151-7.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4591256

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26114173?tool=bestpractice.com

Gene expression also appears to normalize with successful treatment. This test is currently being commercialized.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including esophageal rings, linear furrows, edema, mild white plaques, and narrowingFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including esophageal rings, linear furrows, edema, mild white plaques, and narrowingFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including white plaques, linear furrows, and edemaFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Endoscopic findings including white plaques, linear furrows, and edemaFrom the collection of Dr Evan S. Dellon [Citation ends].