Noonan syndrome is a relatively common, autosomal-dominant, inherited disorder.

Characteristic phenotype includes short stature, chest deformity, congenital heart defects, and unusual facial features.

Boys frequently present with cryptorchidism and manifest delayed puberty.

Caused by activating mutations in multiple genes in the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway. The most commonly implicated gene is PTPN11.

Treatment focuses on the individual symptom, and may include surgery for undescended testes in boys, optimization of cardiac function, and growth hormone treatment for short stature.

The majority of patients lead normal lives. Prognosis is largely dependent on the type and severity of cardiac disease, which may occur in 50% to 80% of cases.

Noonan syndrome (NS) is a relatively common, autosomal-dominant, inherited disorder that is predominantly characterized by short stature, subtle facial dysmorphisms, chest deformity, congenital heart disease, and variable degrees of developmental delay.[1]Jorge AA, Malaquias AC, Arnhold IJ, et al. Noonan syndrome and related disorders: a review of clinical features and mutations in genes of the RAS/MAPK pathway. Horm Res. 2009;71(4):185-93.

https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/201106

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19258709?tool=bestpractice.com

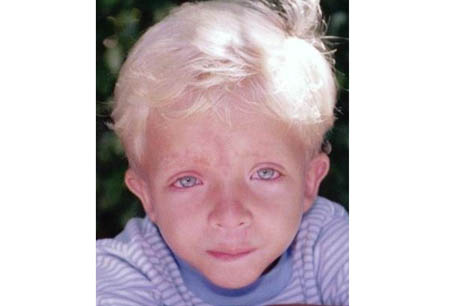

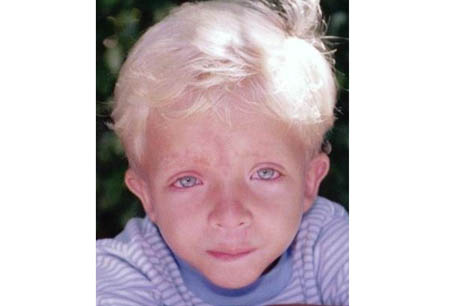

Coagulation defects, cryptorchidism in men, and lymphatic dysplasia are not uncommon.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Boy (6 years of age) with Noonan syndromeFrom the collection of Judith E. Allanson [Citation ends].

The syndrome is thought to be caused primarily by gain-of-function (activating) mutations in genes in the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway.[2]Kratz CP, Niemeyer CM, Castleberry RP, et al. The mutational spectrum of PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Noonan syndrome/myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2005 Sep 15;106(6):2183-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1895140

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15928039?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Roberts AE, Araki T, Swanson KD, et al. Germline gain-of-function mutations in SOS1 cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007 Jan;39(1):70-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17143285?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Tartaglia M, Pennacchio LA, Zhao C, et al. Gain-of-function SOS1 mutations cause a distinctive form of Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007 Jan;39(1):75-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17143282?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Pandit B, Sarkozy A, Pennacchio LA, et al. Gain-of-function RAF1 mutations cause Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2007 Aug;39(8):1007-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17603483?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Razzaque MA, Nishizawa T, Komoike Y, et al. Germline gain-of-function mutations in RAF1 cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007 Aug;39(8):1013-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17603482?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Schubbert S, Zenker M, Rowe SL, et al. Germline KRAS mutations cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2006 Mar;38(3):331-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16474405?tool=bestpractice.com

[8]Cirstea IC, Kutsche K, Dvorsky R, et al. A restricted spectrum of NRAS mutations causes Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010 Jan;42(1):27-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3118669

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19966803?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Nyström AM, Ekvall S, Berglund E, et al. Noonan and cardio-facio-cutaneous syndromes: two clinically and genetically overlapping disorders. J Med Genet. 2008 Aug;45(8):500-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18456719?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Sarkozy A, Carta C, Moretti S, et al. Germline BRAF mutations in Noonan, LEOPARD, and cardiofaciocutaneous syndromes: molecular diversity and associated phenotypic spectrum. Hum Mutat. 2009 Apr;30(4):695-702.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4028130

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19206169?tool=bestpractice.com

Genes implicated include: PTPN11, SOS1, RAF1, RIT1, RASA2, LZTR1, SOS2, CBL, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, PPP1CB, and MAP2K1. The most commonly identified genetic mutation involves PTPN11.[2]Kratz CP, Niemeyer CM, Castleberry RP, et al. The mutational spectrum of PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Noonan syndrome/myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2005 Sep 15;106(6):2183-5.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1895140

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15928039?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Tartaglia M, Mehler EL, Goldberg R, et al. Mutations in PTPN11, encoding the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2, cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001 Dec;29(4):465-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11704759?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Tartaglia M, Kalidas K, Shaw A, et al. PTPN11 mutations in Noonan syndrome: molecular spectrum, genotype-phenotype correlation, and phenotypic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 2002 Jun;70(6):1555-63.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC379142

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11992261?tool=bestpractice.com

Noonan syndrome caused by SHOC2 mutation is now considered by most to be an overlapping condition with unusual features (loose anagen hair); some consider it to be a distinct condition, while others consider it to be classified only as Noonan syndrome.