Various patient factors will influence the type of therapy recommended, including:

The presence or absence of symptoms

Cardiac function and severity of stenosis

Presence and severity of concomitant coronary artery disease and/or other valvular disease

Suitability for surgery and assessment of surgical risk.

The primary treatment of symptomatic AS is aortic valve replacement (AVR). AVR:

Is recommended in symptomatic patients with severe AS, including those with low-flow/low-gradient severe AS with either a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and persistent severe AS on low-dose dobutamine stress study, or a normal LVEF and evidence that valve obstruction is the most likely cause of symptoms.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Is recommended in asymptomatic patients with severe AS who have an LVEF <50% or who are undergoing other cardiac surgery.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

May be considered in asymptomatic patients with very severe AS or severe AS with rapid progression, an abnormal exercise test, or elevated serum B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Symptom onset is a significant milestone and indicates a poor prognosis, with an average survival of only 2 to 5 years without valve replacement. Advances in prosthetic-valve design, cardiopulmonary bypass, surgical technique, and anaesthesia have steadily improved outcomes for aortic valve replacement.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends referral to a specialist for adults with:[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

Clinical decisions

Historically, the choice between surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) (also known as transcatheter aortic valve implantation, or TAVI) was mainly based on surgical risk (i.e., lower risk patients tended toward SAVR and higher risk patients toward TAVR).

Contemporary guidelines (e.g., from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [ACC/AHA]), support the concept of matching the 'durability of the patient' with the 'durability of the valve'.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Evidence suggests that transcatheter valve durability is similar to surgical valve durability.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

According to the ACC/AHA guidelines, in patients with severe AS, the choice of intervention (TAVR vs. SAVR) and the type of valve (mechanical vs. bioprosthetic) should be based primarily on symptoms or reduced ventricular systolic function; this, should be a shared decision-making discussion between the clinician and the patient, who must consider the lifetime risks and benefits associated with each approach.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Early intervention may be considered in patients with rapid progression AS, very severe AS, or if indicated by exercise test results or biomarkers.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

According to the ACC/AHA, in general in patients with an indication for aortic valve replacement:[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

SAVR is preferred for patients aged <65 years or with a life expectancy >20 years. This includes patients with an LVEF <50%.

TAVR is preferred for patients aged >80 years or with a life expectancy <10 years.

Either TAVR or SAVR may be reasonable for patients aged 65-80 years. In these patients, the decision of whether to perform SAVR or TAVR should be based on the patient wishes, anatomical considerations, concomitant coronary artery disease and/or other valvular heart disease, comorbidities (e.g., frailty, dementia), and surgical risk.

The European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACS) strongly recommend early intervention in symptomatic severe AS. The only exceptions are for those in whom intervention is unlikely to improve quality of life, or those with concomitant conditions associated with survival <1 year (e.g., malignancy).[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

The ESC/EACS specifically recommend:[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

Intervention for all patients with symptomatic AS that is:

Severe, high-gradient (defined as a mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, peak velocity ≥4.0 m/s, and valve area ≤1.0 cm²)

Severe low-flow (SVi ≤35 mL/m²), low-gradient (<40 mmHg) AS with reduced ejection fraction (<50%), and evidence of flow (contractile) reserve.

Intervention should be considered for patients with low-flow, low-gradient (<40 mmHg) symptomatic AS and:

Normal ejection fraction after careful confirmation that the AS is severe

Reduced ejection fraction without flow (contractile) reserve, particularly when cardiac computed tomography (CT) calcium scoring confirms severe AS.

According to the ESC/EACS, in general in patients with an indication for aortic valve replacement:[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

NICE in the UK recommends intervention for any patient with symptomatic AS.[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

NICE further recommends to consider referral for intervention, if suitable, if the patient has:[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

NICE recommends:[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

SAVR preferentially for patients with severe AS if they are suitable for surgery, either by median sternotomy or minimally invasive surgery if there is an indication for surgery and they are at low or intermediate surgical risk.

NICE recommends basing the decision on the type of surgery (median sternotomy or minimally invasive surgery) on patient characteristics and preferences. If minimally invasive surgery is the most suitable option but is not available locally, NICE recommends referring the patient to another centre.[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

TAVR for patients with severe AS if surgery is unsuitable, or non-bicuspid severe AS with high surgical risk, including those with:

An unacceptably high risk of mortality or morbidity due to surgery (e.g., risk of infection in patients who are immunosuppressed)

Who are expected to have unacceptably strenuous and prolonged recovery from surgery and an extended need for rehabilitation due to frailty, reduced mobility, or musculoskeletal conditions

With a low life expectancy, either because of their age, or because they have life-limiting comorbidities.

NICE also recommends that:[45]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis. Jul 2017 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg586

Suitability for TAVR should be determined by an experienced multidisciplinary team. This team must include interventional cardiologists who are experienced in the procedure, cardiac surgeons, an expert in cardiac imaging, and (where appropriate) a cardiac anaesthetist and a geriatrician. NICE advises that suitability for TAVR depends on:[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

An appropriate access for inserting the TAVR catheter

The morphology of the valve, aortic root, and ascending aorta

The degree and distribution of calcium in the aortic valve.

Details of all patients should be entered into the UK TAVR registry.[45]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis. Jul 2017 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg586

TAVR should only be performed in specialised centres and only by clinicians and teams who have specialised training in complex endovascular interventions. It is recommended that units doing this procedure should have both cardiac and vascular support in order to manage complications in an emergency, and ongoing patient care.[45]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for aortic stenosis. Jul 2017 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg586

If the patient has an indication for intervention, NICE recommends discussing the possible benefits and risks with the patient; include in this discussion:[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

The long and short term benefits to quality of life

Prosthetic valve durability

The risks associated with the procedures

The type of access required for surgery (median sternotomy, minimally invasive surgery, or transcatheter [for patients at high surgical risk])

The possible need for other cardiac procedures in future.

Assessment of surgical risk

The decision to refer patients for SAVR or TAVR depends in part on their estimated risk of operative mortality. Surgical risk can be estimated using scoring systems such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) and the EuroScore II.[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

Society of Thoracic Surgeons: risk calculator

Opens in new window These models utilise a variety of risk factors to predict postoperative outcome after valve surgery. Mortality estimates are used in conjunction with assessments of frailty, major organ system compromise, and procedure-specific impediments to classify each patient's overall surgical risk:[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Low risk

Intermediate risk

High risk

Prohibitive risk

Treatment decisions in elderly and frail patients

Patients with terminal illness, significant dementia, or advanced comorbidities in whom valve replacement would not be expected to provide a meaningful improvement in life will typically not be referred for valve replacement.

Bear in mind, however, that NICE in the UK specifically recommends that TAVR may be considered in patients who have a low life expectancy (either because of their age or because they have life-limiting comorbidities).[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

Surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)

Prosthetic aortic valves used in surgical valve replacement may be mechanical or bioprosthetic. The type of prosthesis used depends on patient preference, but there has been a trend towards greater utilisation of bioprosthetic valves in recent years.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

[46]Brown JM, O'Brien SM, Wu C, et al. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Jan;137(1):82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19154908?tool=bestpractice.com

Each type has relative merits and drawbacks.

Mechanical valves:

Reasonable for patients less than 50 years of age who do not have a contraindication to anticoagulation. For patients aged 50 to 65 years and no contraindication to anticoagulation, it is reasonable to individualise the choice of either a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve on the basis of individual patient factors and preferences.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Less prone to degeneration and subsequent re-operation for valve failure compared with bioprosthetic valves.

Patients require subsequent systemic anticoagulation (with the associated risk of bleeding) to prevent valve thrombosis.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

[  ]

In people with prosthetic heart valves, what are the effects of combined antiplatelet and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) therapy compared with VKA monotherapy?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.406/fullShow me the answer Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are not recommended in patients requiring long-term anticoagulation for a mechanical valve regardless of co-existing atrial fibrillation.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

]

In people with prosthetic heart valves, what are the effects of combined antiplatelet and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) therapy compared with VKA monotherapy?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.406/fullShow me the answer Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are not recommended in patients requiring long-term anticoagulation for a mechanical valve regardless of co-existing atrial fibrillation.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Bioprosthetic valves:

Recommended in patients of any age for whom anticoagulation therapy is contraindicated, cannot be managed, or is not desired.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Bioprosthetic valves are also reasonable for patients more than 65 years of age. For patients aged 50 to 65 years, it is reasonable to individualise the choice of either a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve on the basis of individual patient factors and preferences.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

More prone to degeneration and subsequent re-operation for valve failure compared with mechanical valves.

Patients do not need systemic anticoagulation, except in the presence of atrial fibrillation, where anticoagulation is indicated.

Outcome data comparing bioprosthetic and mechanical valves are difficult to interpret because bioprosthetic valve technology has improved significantly since the time of the largest randomised trials. Studies using first-generation bioprosthetic valves found a trend towards improved survival with mechanical valves.[47]Hammermeister K, Sethi GK, Henderson WG, et al. Outcomes 15 years after valve replacement with a mechanical versus a bioprosthetic valve: final report of the Veterans Affairs randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 Oct;36(4):1152-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11028464?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Rahimtoola SH. Choice of prosthetic heart valve for adult patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003 Mar 19;41(6):893-904.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12651032?tool=bestpractice.com

In contrast, newer studies have found no differences in mortality after correcting for preoperative severity of heart disease, regardless of age. They do note that bioprosthetic valves are more likely to require re-operation for valve failure.[49]Stassano P, Di Tommaso L, Monaco M, et al. Aortic valve replacement: a prospective randomized evaluation of mechanical versus biological valves in patients ages 55 to 70 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Nov 10;54(20):1862-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19892237?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Lund O, Bland M. Risk-corrected impact of mechanical versus bioprosthetic valves on long-term mortality after aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006 Jul;132(1):20-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16798297?tool=bestpractice.com

Overall, there is a trend among surgeons towards greater use of bioprosthetic valves. From 1997 to 2006, the usage of bioprosthetic valves in North America increased from 44.0% to 78.4%.[46]Brown JM, O'Brien SM, Wu C, et al. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Jan;137(1):82-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19154908?tool=bestpractice.com

This trend reflects greater confidence in the durability of second- and third-generation bioprosthetic valves.

Choices regarding types of aortic valve prosthesis must balance the risk of bleeding due to the need for systemic anticoagulation with mechanical valves, versus the increased possibility of re-operation with bioprosthetic valves.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR)

In the US and some European countries, the number of TAVR procedures performed annually surpasses the number of isolated surgical aortic valve replacements.[51]Kundi H, Strom JB, Valsdottir LR, et al. Trends in isolated surgical aortic valve replacement according to hospital-based transcatheter aortic valve replacement volumes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 12;11(21):2148-56.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1936879818314377?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30343022?tool=bestpractice.com

The procedure builds on the current techniques employed in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory for coronary angiography and intervention. Unlike surgical valve replacement, TAVR is done on the beating heart without the need for a sternotomy or cardiopulmonary bypass. Instead, catheters are introduced into the heart via several potential arterial access points, and a stent-mounted prosthetic valve is placed within the native aorta. Several different transcatheter heart valves exist, each with a unique delivery system and technique, but the basic premise remains the same. The advantages of this minimally invasive approach include the avoidance of cardiopulmonary bypass and median sternotomy. These benefits have allowed invasive cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons to offer aortic valve replacement to sicker and more complex patients.

TAVR in high-risk patients

In the US PARTNER study comparing high-risk surgery and TAVR in high-risk patients, mortality and symptom reduction were similar at 2 and 5 years for each modality.[52]Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 3;366(18):1686-95.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22443479?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2477-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25788234?tool=bestpractice.com

Peri-procedural risks varied at 30 days; vascular complications and neurological events such as stroke occurred more frequently after TAVR in early experiences using first and second generation devices that required very large sheath delivery system sizes, while major bleeding and new-onset atrial fibrillation more commonly followed surgery.[54]Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 9;364(23):2187-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21639811?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Généreux P, Cohen DJ, Williams MR, et al. Bleeding complications after surgical aortic valve replacement compared with transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the PARTNER I Trial (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Mar 25;63(11):1100-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24291283?tool=bestpractice.com

Acute kidney injury and new pacemaker implantation were complications of both interventions at similar rates.[54]Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 9;364(23):2187-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21639811?tool=bestpractice.com

Scores on health-related quality-of-life assessments improved more rapidly with TAVR but were similar at 12 months.[56]Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Wang K, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: results from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) trial (Cohort A). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Aug 7;60(6):548-58.

http://content.onlinejacc.org/article.aspx?articleID=1270594

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22818074?tool=bestpractice.com

At 2 and 5 years, echocardiographic improvements in valve area and mean gradients were similar in both groups, but total and paravalvular aortic regurgitation was encountered more frequently after TAVR.[52]Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 3;366(18):1686-95.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22443479?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2477-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25788234?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Hahn RT, Pibarot P, Stewart WJ, et al. Comparison of transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement in severe aortic stenosis: a longitudinal study of echocardiography parameters in cohort A of the PARTNER trial (placement of aortic transcatheter valves). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jun 25;61(25):2514-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23623915?tool=bestpractice.com

A randomised trial comparing TAVR using an alternative, self-expanding bioprosthesis to surgery in high-risk patients demonstrated similar survival at 5 years with TAVR compared with surgery.[58]Gleason TG, Reardon MJ, Popma JJ, et al. 5-year outcomes of self-expanding transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 4;72(22):2687-96.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109718382901?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30249462?tool=bestpractice.com

It must be emphasised that, despite the encouraging results, TAVR is a relatively new technology and it is unclear at this time how the durability of transcatheter valves will compare with surgical prostheses.

For patients with prohibitive surgical risk (i.e., surgical non-candidates), TAVR is the preferred treatment modality.[59]Holmes DR Jr, Mack MJ, Kaul S, et al. 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS expert consensus document on transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Mar 27;59(13):1200-54.

http://content.onlinejacc.org/article.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22300974?tool=bestpractice.com

The PARTNER trial comparing standard therapy, including balloon aortic valvuloplasty, with TAVR in inoperable patients demonstrated a 20% absolute reduction in mortality at 1 year in favour of TAVR.[60]Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 21;363(17):1597-607.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1008232#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20961243?tool=bestpractice.com

At 3 years, mortality with TAVR was 54.1% compared with 80.9% with standard therapy, while at 5 years, mortality was 71.8% and 93.6%, respectively.[61]Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Makkar RR, et al. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation. 2014 Oct 21;130(17):1483-92.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/130/17/1483.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25205802?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Kapadia SR, Leon MB, Makkar RR, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard treatment for patients with inoperable aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 20;385(9986):2485-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25788231?tool=bestpractice.com

Heart failure symptoms improved between 30 days and 6 months. At 3 years, 29.7% of patients in the TAVR group were alive with New York Heart Association Class I/II symptoms, compared with 4.8% of patients in the standard therapy group.[60]Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 21;363(17):1597-607.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1008232#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20961243?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Makkar RR, et al. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation. 2014 Oct 21;130(17):1483-92.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/130/17/1483.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25205802?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 3;366(18):1696-704.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22443478?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients treated with TAVR also showed significant improvements on assessments of health-related quality of life when compared with those receiving standard therapy.[64]Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Lei Y, et al. Valvular heart disease: Health-related quality of life after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2011 Nov 1;124(18):1964-72.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/124/18/1964.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21969017?tool=bestpractice.com

TAVR in intermediate- and low-risk patients

Clinical trial data in intermediate-risk and low-risk patients suggest that TAVR is a reasonable alternative to surgery.

The PARTNER 2A study in intermediate-risk patients with severe AS demonstrated similar rates of death or disabling stroke at 2 years and 5 years with TAVR compared with surgery, while an alternate randomised trial of a self-expanding prosthesis also showed noninferiority at 2 years with TAVR.[65]Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER 2 Investigators. Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016 Apr 28;374(17):1609-20.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1514616

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27040324?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Makkar RR, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, et al. Five-year outcomes of transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 27;382(9):799-809.

https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910555

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31995682?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al; SURTAVI Investigators. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 6;376(14):1321-31.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28304219?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients undergoing TAVR implantation via a transfemoral approach rather than a transthoracic one, there was a trend towards a lower risk of death or disabling stroke compared with surgery. A meta-analysis that included the PARTNER 2A study (2 year results) found that transfemoral TAVR may be beneficial compared with surgical aortic valve replacement in many patients, particularly those who have a shorter life expectancy.[68]Siemieniuk RA, Agoritsas T, Manja V, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis at low and intermediate risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016 Sep 28;354:i5130.

http://www.bmj.com/content/354/bmj.i5130.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27683246?tool=bestpractice.com

In low-risk patients with anatomy favourable for transfemoral TAVR, the PARTNER 3 study showed that TAVR outperformed surgery at reducing a composite of death, stroke, or rehospitalisation at 1 year, while a second study of TAVR in low-risk patients using an alternative self-expanding prosthesis showed similar rates of a composite of death or disabling stroke between TAVR and surgery.[69]Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380(18):1695-705.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1814052

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30883058?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 2;380(18):1706-15.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1816885

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30883053?tool=bestpractice.com

Of note, the average age of patients in the two pivotal TAVR low-risk trials was >70 years. Therefore, data from these trials should not be extrapolated to patients at considerably younger ages. A Cochrane review found that there is probably little or no mortality difference between TAVR and surgery for severe AS in low-risk patients, and probably little or no difference in risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiac death.[71]Kolkailah AA, Doukky R, Pelletier MP, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in people with low surgical risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Dec 20;12:CD013319.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013319.pub2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31860123?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

How does transcatheter aortic valve implantation compare with surgical aortic valve replacement for adults with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2927/fullShow me the answer The Cochrane review found that TAVR reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury, and bleeding, and may reduce the risk of hospitalisation, but there is an increased risk of permanent pacemaker implantation. It should be noted that further study is needed to determine the long-term durability of transcatheter valves, and longer-term follow-up data from these trials in low-risk patients will permit a more complete evaluation of specific outcomes such as survival and complication rates.

]

How does transcatheter aortic valve implantation compare with surgical aortic valve replacement for adults with severe aortic stenosis at low surgical risk?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2927/fullShow me the answer The Cochrane review found that TAVR reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury, and bleeding, and may reduce the risk of hospitalisation, but there is an increased risk of permanent pacemaker implantation. It should be noted that further study is needed to determine the long-term durability of transcatheter valves, and longer-term follow-up data from these trials in low-risk patients will permit a more complete evaluation of specific outcomes such as survival and complication rates.

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty

For patients with severe AS who are critically ill, need urgent non-cardiac surgery, have cancer and an unclear long-term survival, are acutely symptomatic, or are in cardiogenic shock, balloon valvuloplasty is a reasonable option as a bridge to recovery and subsequent evaluation for SAVR or TAVR.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Balloon valvuloplasty may also be used in patients with decompensated AS and in those with severe AS who require urgent high-risk non-cardiac surgery.[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

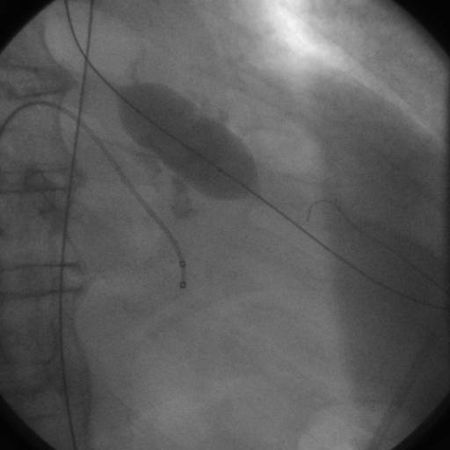

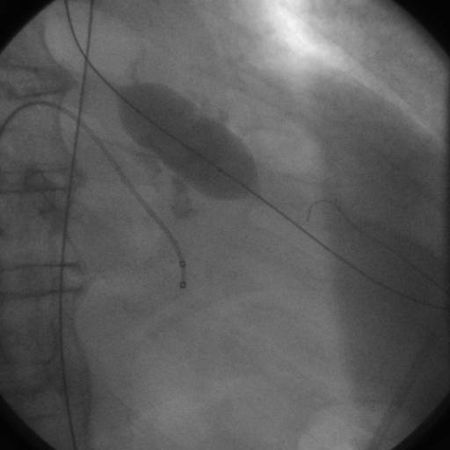

This percutaneous procedure done in the cardiac catheterisation lab in which a balloon is forcefully inflated across the aortic valve to relieve stenosis. Unfortunately, re-stenosis rates are high at 6 months and there is no shown improvement in mortality following valvuloplasty. However, patients do generally experience improvement in haemodynamics and symptoms, which may provide an opportunity for more definitive care.[72]Letac B, Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Evaluation of restenosis after balloon dilatation in adult aortic stenosis by repeat catheterization. Am Heart J. 1991 Jul;122(1 Pt 1):55-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2063763?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Balloon valvuloplasty fluoroscopy film that demonstrates valvuloplasty balloon inflated across a calcified aortic valveFrom the collection of David Liff, MD, Emory University Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

Medical therapy

Medical therapies do not influence the natural history of AS. However, medical therapy for certain comorbidities, such as for hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, is appropriate in patients with AS and hypertension and/or coronary artery disease.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Studies have shown that renin-angiotensin system blocker therapy (ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker) may reduce the long-term risk of all-cause mortality in patients who have undergone SAVR or TAVR and may be considered in these patients (provided that blood pressure is carefully monitored).[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

While the role of statin therapy is established for atherosclerotic disease prevention, randomised trials of statins in patients with AS have not found improvements in AS progression.[19]Cowell SJ, Newby DE, Prescott RJ, et al. A randomized trial of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in calcific aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 9;352(23):2389-97.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa043876#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15944423?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, et al; SEAS Investigators. Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Sep 25;359(13):1343-56.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0804602#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18765433?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]Chan KL, Teo K, Dumesnil JG, et al; ASTRONOMER Investigators. Effect of lipid lowering with rosuvastatin on progression of aortic stenosis: results of the aortic stenosis progression observation: measuring effects of rosuvastatin (ASTRONOMER) trial. Circulation. 2010 Jan 19;121(2):306-14.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/121/2/306.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20048204?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

How do statins compare with placebo in people with aortic valve stenosis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2115/fullShow me the answer However, studies in patients with mild to moderate AS have shown a reduction of ischaemic events by 20% in those treated with statins.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

]

How do statins compare with placebo in people with aortic valve stenosis?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.2115/fullShow me the answer However, studies in patients with mild to moderate AS have shown a reduction of ischaemic events by 20% in those treated with statins.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

The ACC/AHA recommends statin therapy for primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerosis in all patients with calcific AS on the basis of standard risk scores.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

NICE in the UK recommends considering aspirin (or clopidogrel if aspirin is not tolerated) if the patient has undergone TAVR. However, NICE does not recommend anticoagulation following surgical biological valve replacement, unless there is a separate indication for anticoagulation.[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

Asymptomatic AS

Severe AS

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend:[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

SAVR in asymptomatic patients with severe AS and an LVEF <50%, who are aged <65 years or have a life expectancy >20 years.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Studies have reported significant differences in survival, beginning as early as 3 years post-valve replacement, between those with preoperative LVEF >50% and patients with LVEF <50%.[75]Schwarz F, Baumann P, Manthey J, et al. The effect of aortic valve replacement on survival. Circulation. 1982;66:1105-1110.

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/66/5/1105.full.pdf+html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7127696?tool=bestpractice.com

Delaying surgery in these patients may lead to irreversible LV dysfunction and worsened survival.

Either TAVR or SAVR in asymptomatic patients with severe AS and an LVEF <50%, who are 65 to 80 years of age and have no contraindications to transfemoral TAVR, after shared decision-making based on the patient wishes, anatomical considerations, concomitant coronary artery disease and/or other valvular heart disease, comorbidities (e.g., frailty, dementia), and surgical risk.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

TAVR in preference to SAVR in asymptomatic patients with severe AS and LVEF <50% who are of any age and have:[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

A life expectancy <10 years and no contraindication to transfemoral TAVR

A high or prohibitive surgical risk, if the predicted post-TAVR survival is >12 months with an acceptable quality of life.

SAVR in preference to TAVR in asymptomatic patients with severe AS and low surgical risk who have an abnormal exercise test, very severe AS, rapid progression, or elevated serum B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Considering SAVR in asymptomatic patients with severe AS and normal LV systolic function at rest and low surgical risk, when there is a progressive decrease in LVEF on at least three serial imaging studies to <60% without an alternative cause.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

There is a sizable population of patients with severe AS who are asymptomatic, with normal LV systolic function, and not requiring other types of cardiac surgery. The first determination to be made in these patients is that they are truly without symptoms, using a thorough history focused on activity level and changes in functional capacity. For those without symptoms, exercise testing may provide clinically important information.[35]Généreux P, Stone GW, O'Gara PT, et al. Natural history, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic strategies for patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 May 17;67(19):2263-88.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109716010287?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27049682?tool=bestpractice.com

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that patients with asymptomatic severe AS undergo serial evaluation with transthoracic echocardiography every 6 to 12 months.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

These patients must also be followed up closely by a cardiologist.

The ESC/EACS recommend:[44]Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Feb 12;43(7):561-632.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453165?tool=bestpractice.com

NICE in the UK recommends that adults with asymptomatic severe AS have a clinical review every 6 to 12 months (which should include echocardiography) if an intervention is suitable but not currently needed. NICE advises basing the frequency of review on the echocardiography findings and shared decision making with the patient.[28]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heart valve disease presenting in adults: investigation and management. Nov 2021 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng208

Moderate or mild AS

The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend:[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

When patients with moderately stenotic valves undergo cardiac surgery, the decision to replace the valve is more difficult and balances the increased risk of adding aortic valve replacement to the planned surgery with the future likelihood of AS progressing to a severe, symptomatic state. Aortic valve replacement with either TAVR or SAVR may be considered for asymptomatic patients with moderate AS who are undergoing other cardiac surgery.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary bypass surgery has been studied, though no large prospective, randomised controlled trials exist. A review of outcomes from 1995 to 2000 of the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) database found that if patients had a peak aortic gradient >30 mmHg and were <70 years (correlating with a more moderate degree of stenosis), they benefited from prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary artery bypass surgery.[76]Smith WT 4th, Ferguson TB Jr, Ryan T, et al. Should coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients with mild or moderate aortic stenosis undergo concomitant aortic valve replacement? A decision analysis approach to the surgical dilemma. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1241-1247.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15364326?tool=bestpractice.com

These conclusions were supported by a subsequent retrospective analysis that found a significant survival advantage at 8 years in favour of prophylactic valve replacement at the time of bypass surgery for those with moderate but not mild AS.[77]Pereira JJ, Balaban K, Lauer MS, et al. Aortic valve replacement in patients with mild or moderate aortic stenosis and coronary bypass surgery. Am J Med. 2005;118:735-742.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15989907?tool=bestpractice.com

Serial transthoracic echocardiograms in asymptomatic patients with mild stenosis is recommended every 3 to 5 years.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

People with moderate stenosis are recommended to have transthoracic echocardiograms every 1 to 2 years.[26]Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e72-227.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

]

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are not recommended in patients requiring long-term anticoagulation for a mechanical valve regardless of co-existing atrial fibrillation.[26]

]

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are not recommended in patients requiring long-term anticoagulation for a mechanical valve regardless of co-existing atrial fibrillation.[26] ]

The Cochrane review found that TAVR reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury, and bleeding, and may reduce the risk of hospitalisation, but there is an increased risk of permanent pacemaker implantation. It should be noted that further study is needed to determine the long-term durability of transcatheter valves, and longer-term follow-up data from these trials in low-risk patients will permit a more complete evaluation of specific outcomes such as survival and complication rates.

]

The Cochrane review found that TAVR reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation, acute kidney injury, and bleeding, and may reduce the risk of hospitalisation, but there is an increased risk of permanent pacemaker implantation. It should be noted that further study is needed to determine the long-term durability of transcatheter valves, and longer-term follow-up data from these trials in low-risk patients will permit a more complete evaluation of specific outcomes such as survival and complication rates.

]

However, studies in patients with mild to moderate AS have shown a reduction of ischaemic events by 20% in those treated with statins.[26]

]

However, studies in patients with mild to moderate AS have shown a reduction of ischaemic events by 20% in those treated with statins.[26]