Aetiology

Calcification and fibrosis of normal trileaflet valves is the most common cause of AS in adults and accounts for as many as 80% of cases in the US and Europe.[8] Calcific aortic disease represents a spectrum ranging from aortic sclerosis (defined as leaflet thickening without obstruction) to severe AS. Risk factors associated with aortic sclerosis include smoking, hypertension, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, elevated C-reactive protein, and elevated lipoprotein(a).[9] Retrospective studies have shown that high LDL-cholesterol levels and smoking are associated with progression to AS, but causality has not been confirmed.[10]

Congenitally bicuspid valves account for the majority of the remainder of cases. This is the most common cause of AS in younger patients.[3] Patients with coarctation of the aorta and Turner syndrome have a higher incidence of bicuspid valves.

Rheumatic heart disease has historically been an important cause of AS, but due to improvements in treatment, it is now uncommon in industrialised countries. Rheumatic heart disease remains prevalent in developing nations.

Other circumstances including connective tissue diseases, radiotherapy, and hyperlipoproteinaemia syndromes can cause AS, but these are unusual consequences of rare conditions.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with abnormal calcium homeostasis, and it has been shown that AS progresses faster in patients with CKD.[11][12]

Pathophysiology

Aortic calcification is no longer thought to reflect age-related wear and tear, and is recognised to be an active process. The valvular endocardium is damaged as the result of abnormal blood flow across the valve (in the case of a bicuspid valve) or by an unknown trigger (as may be the case for tricuspid valves). Endocardial injury initiates an inflammatory process similar to atherosclerosis and ultimately leads to leaflet fibrosis and deposition of calcium on the valve. Fibrosis and calcification occur slowly and are subclinical until the disease is fairly advanced. Progressive fibrosis and calcium deposition limit aortic leaflet mobility and eventually produce stenosis.

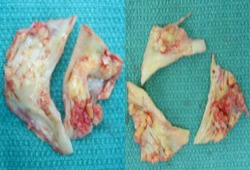

Unicuspid and bicuspid valves experience abnormal shear and mechanical stresses from birth. Therefore, the pathological processes and resultant stenosis occur earlier than in trileaflet valves.[6][7][13][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bicuspid and trileaflet aortic valves with severe calcification following surgical excisionFrom the collection of David Liff, MD, Emory University Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

In rheumatic disease, an autoimmune inflammatory reaction is triggered by prior Streptococcus infection that targets the valvular endothelium, leading to inflammation and eventually calcification.

Long-standing pressure overload leads to the development of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). This adaptive response permits the ventricle to maintain a normal wall stress (afterload) despite the pressure overload produced by stenosis. As the stenosis worsens, the adaptive mechanism fails and left ventricular wall stress increases. Systolic function declines as wall stress increases, with resultant systolic heart failure.

LVH is a contributing factor to many of the symptoms seen in AS. The consequence of concentric LVH is a smaller, less compliant chamber. Thus, left ventricle end-diastolic pressure is increased, especially during periods of increased cardiac output (e.g., exercise), leading to the sensation of dyspnoea and eventually diastolic heart failure, which typically precedes systolic dysfunction. Furthermore, in LVH, myocardial oxygen demand is greater due to increased left ventricular mass, while coronary blood flow may be reduced through a variety of mechanisms. Thus, even patients who lack coronary atherosclerotic disease may develop symptoms of anginal chest pain.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer