MCC is a rare, aggressive cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy that carries a high risk of metastasis to regional lymph nodes and distant organ sites and has a higher case fatality rate than melanoma.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

The primary cutaneous tumour typically presents as a solitary, non-specific, rapidly growing nodule or plaque, generally on sun-exposed white people who are >65 years of age and/or immunosuppressed.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Nov;49(5):832-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14576661?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):1-12.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.22765

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17520670?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Güler-Nizam E, Leiter U, Metzler G, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors of Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 2009 Jul;161(1):90-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19438439?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010 Jan;37(1):20-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19638070?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al. Recurrence and survival in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy for Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 153 patients from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 Sep;18(9):2529-37.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4117701

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21431988?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al. Five hundred patients with Merkel cell carcinoma evaluated at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2011 Sep;254(3):465-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21865945?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Tarantola TI, Vallow LA, Halyard MY, et al. Unknown primary Merkel cell carcinoma: 23 new cases and a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Mar;68(3):433-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23182060?tool=bestpractice.com

[36]Sridharan V, Muralidhar V, Margalit DN, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: a population analysis on survival. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016 Oct;14(10):1247-57.

https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/14/10/article-p1247.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27697979?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Bleicher J, Asare EA, Flores S, et al. Oncologic outcomes of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC): a multi-institutional cohort study. Am J Surg. 2021 Apr;221(4):844-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32878692?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Wang AJ, McCann B, Soon WCL, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: a forty-year experience at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. BMC Cancer. 2023 Jan 7;23(1):30.

https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-022-10349-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36611133?tool=bestpractice.com

The diagnosis is confirmed with skin biopsy and histopathological evaluation.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer. 2008 Nov 1;113(9):2549-58.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.23874

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18798233?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnosis of MCC requires a high index of suspicion, because the primary tumour lacks distinguishing features and is usually asymptomatic.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Always ensure prompt biopsy of any asymptomatic nodule or plaque that is firm, red or flesh-coloured, and expanding rapidly.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

MCC is often initially misdiagnosed clinically as a benign lesion. In one prospective cohort study of 195 patients with MCC, 56% of lesions were presumed by the physician to be benign; the most common incorrect diagnosis (32%) was a cyst or acneiform lesion.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

The clinical differential diagnosis includes other types of skin cancer such as basal or squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma, or a benign skin lesion such as an epidermal inclusion cyst or a pyogenic granuloma. Another differential diagnosis to consider would be cutaneous metastasis of a primary visceral tumour, such as metastatic small cell lung cancer, which has similar histopathology to MCC; immunohistochemistry, and sometimes imaging, is needed to distinguish between the two.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

It is important to diagnose MCC early because the 5-year overall survival for stage IV disease (distant metastases) has been reported at just 14% to 29%, whereas the prognosis is significantly better for earlier stages.[10]Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23(11):3564-71.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8881989

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198511?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Use the mnemonic AEIOU to recall five common presenting features of MCC. The presence of three or more should prompt suspicion of the diagnosis.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Spada F, Bossi P, Caracò C, et al; DELPHI Panel Members. Nationwide multidisciplinary consensus on the clinical management of Merkel cell carcinoma: a Delphi panel. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jun;10(6):e004742. [Erratum in: J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Sep;10(9):e004742corr1.]

https://jitc.bmj.com/content/10/6/e004742

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35701070?tool=bestpractice.com

Bear in mind that not all patients present with all five features; of 62 patients studied, 89% met ≥3 of the AEIOU criteria, 52% met ≥4 criteria, and 7% met all 5 criteria.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness. One study of 195 patients with pathologically confirmed MCC found that 88% of tumours were asymptomatic.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

Expanding rapidly over ≤3 months.

Immunosuppressed. Immunosuppression is an important risk factor for MCC (although it is also important to note that most patients who develop MCC are not immunosuppressed).[30]Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):1-12.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.22765

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17520670?tool=bestpractice.com

Studies have reported that an estimated 6% to 12% of MCC cases are associated with immunosuppression.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Older than 50 years of age. The median age of MCC diagnosis is 77 years.[6]Jacobs D, Huang H, Olino K, et al. Assessment of age, period, and birth cohort effects and trends in Merkel cell carcinoma incidence in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021 Jan 1;157(1):59-65.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/2772469

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33146688?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23(11):3564-71.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8881989

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198511?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultraviolet (UV)-exposed site on a person with light skin. Less than 10% of MCCs occur on partially sun-protected areas (trunk, thighs, and hair-bearing scalp) or on highly sun-protected sites (e.g., buttocks).[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Take a detailed history with a particular focus on:

How long the lesion has been present, whether it has increased in size, and if any other changes have occurred.

Early growth of MCC lesions is typically rapid, over weeks or months.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Although ulceration and bleeding are infrequent at first presentation, they might occur at advanced stages.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Any associated pain or pruritus.

History of UV exposure.[30]Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):1-12.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.22765

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17520670?tool=bestpractice.com

MCC is strongly associated with lower latitudes and a high UV radiation index.[13]Stang A, Becker JC, Nghiem P, et al. The association between geographic location and incidence of Merkel cell carcinoma in comparison to melanoma: an international assessment. Eur J Cancer. 2018 May;94:47-60.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6019703

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29533867?tool=bestpractice.com

The primary tumour typically occurs on sun-exposed skin.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

It may sometimes be commingled with or adjacent to other lesions caused by UV exposure.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Note that UV induction is understood to be one of the two pathogenetic pathways for MCC development; the second pathway is associated with oncogenic transformation by Merkel cell polyomavirus.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Immunosuppression, including any history of haematological malignancies, HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplant, and use of immunosuppressant medications.[30]Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):1-12.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.22765

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17520670?tool=bestpractice.com

MCC is strongly associated with immunosuppression, with an estimated 6% to 12% of all patients with MCC being immunosuppressed.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guideline states that 10% of patients with MCC are organ transplant recipients, or have either a haematological malignancy or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Other risk factors. These include:[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Advancing age. The median age at diagnosis is 77 years.[6]Jacobs D, Huang H, Olino K, et al. Assessment of age, period, and birth cohort effects and trends in Merkel cell carcinoma incidence in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021 Jan 1;157(1):59-65.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/2772469

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33146688?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23(11):3564-71.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8881989

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198511?tool=bestpractice.com

Incidence rates increase with age; the highest incidence is reported in those aged over 85 years.[6]Jacobs D, Huang H, Olino K, et al. Assessment of age, period, and birth cohort effects and trends in Merkel cell carcinoma incidence in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021 Jan 1;157(1):59-65.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/2772469

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33146688?tool=bestpractice.com

Light skin type. MCC is very rare in people who are not white.[5]Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Mar;78(3):457-63.e2.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5815902

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29102486?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010 Jan;37(1):20-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19638070?tool=bestpractice.com

Male sex. Studies have reported that 61% to 66% of cases are in men.[1]Lemos BD, Storer BE, Iyer JG, et al. Pathologic nodal evaluation improves prognostic accuracy in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 5823 cases as the basis of the first consensus staging system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Nov;63(5):751-61.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2956767

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20646783?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Fitzgerald TL, Dennis S, Kachare SD, et al. Dramatic increase in the incidence and mortality from Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. Am Surg. 2015 Aug;81(8):802-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26215243?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Mar;78(3):457-63.e2.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5815902

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29102486?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Nov;49(5):832-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14576661?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23(11):3564-71.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8881989

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198511?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

Perform a thorough examination of any suspicious lesion(s).

The primary cutaneous MCC tumour usually presents as a solitary, firm, rapidly-growing, erythematous or pink-to-violaceous or skin-coloured papule or subcutaneous nodule.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

MCC most frequently develops on the sun-exposed areas of head and neck (29% to 44%) and the extremities (37% to 45%). Less than 10% of MCCs occur on partially sun-protected areas (trunk, thighs, and hair-bearing scalp) or highly sun-protected areas (buttocks). Extra-cutaneous sites (e.g., vulva, vagina, oral mucosa parotid gland, nasal cavity) are very rarely involved.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Note that in black and Hispanic patients, MCC more often presents on sites other than the head and neck.[41]Mohsin N, Martin MR, Reed DJ, et al. Differences in Merkel cell carcinoma presentation and outcomes among racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 May 1;159(5):536-40.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10018402

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36920369?tool=bestpractice.com

MCC lesions are usually asymptomatic and not tender to the touch.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Measure the clinical size of the lesion prior to any biopsy, as the diameter of the primary tumour will determine the T-stage. Moreover, increased clinical tumour diameter and depth are associated with a worse prognosis.[42]Smith FO, Yue B, Marzban SS, et al. Both tumor depth and diameter are predictive of sentinel lymph node status and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2015 Sep 15;121(18):3252-60.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.29452

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26038193?tool=bestpractice.com

The US National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline lists a primary tumour >1 cm as one of several adverse risk factors for a worse outcome, warranting different treatment recommendations.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Dermoscopy for MCC is non-specific, but can show prominent red or milky-red background colour or smaller clods of milky-red areas, polymorphous vessels, and white areas.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

It can be particularly helpful to use dermoscopy for patients with multiple skin lesions as MCC can sometimes be contiguous to, or intermingled with, other skin cancers that can be more easily identified with dermoscopy.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

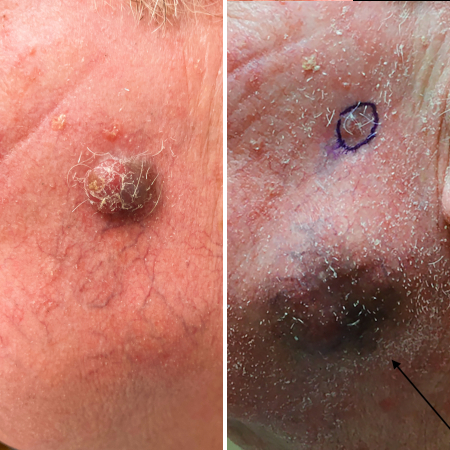

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A primary MCC tumour in an 87-year-old man who presented with a large, fast-growing, red, eroded nodule on the right templeFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A rapidly-growing MCC on the right cheek of a 64-year-old man, which started as a small erythematous cyst-like papule then developed within a few months into a larger, violaceous nodule with associated pruritusFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A rapidly-growing MCC on the right cheek of a 64-year-old man, which started as a small erythematous cyst-like papule then developed within a few months into a larger, violaceous nodule with associated pruritusFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC on the left lower lip of a 68-year-old man. The asymptomatic tumour is an ill-defined reddish-pink, scaly plaque blurring the lower vermillion of the lipFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC on the left lower lip of a 68-year-old man. The asymptomatic tumour is an ill-defined reddish-pink, scaly plaque blurring the lower vermillion of the lipFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Primary MCC on the right frontal scalp (asterisk) of a 73-year-old man, with a biopsy scar of an in-transit metastasis (arrow). The primary tumor initially presented as an asymptomatic, fast-growing subcutaneous nodule that was misdiagnosed as an epidermoid cystFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

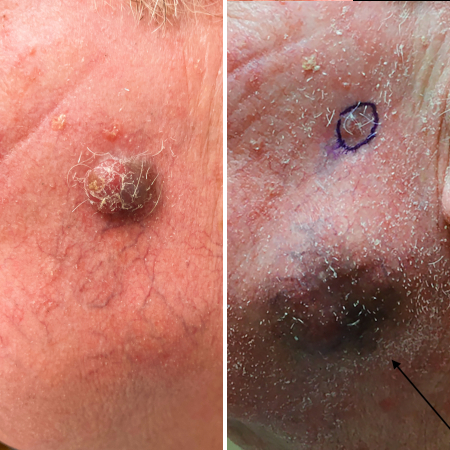

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Primary MCC on the right frontal scalp (asterisk) of a 73-year-old man, with a biopsy scar of an in-transit metastasis (arrow). The primary tumor initially presented as an asymptomatic, fast-growing subcutaneous nodule that was misdiagnosed as an epidermoid cystFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC presenting as a well-defined, rapidly growing, asymptomatic, brightly violaceous nodule on the left cheek of a 71-year-old man. The patient developed a golf-ball sized subcutaneous mass in the left parotid (original biopsy site marked with blue ink, subcutaneous metastasis marked with arrow). Fine needle aspiration of the mass in the left parotid gland confirmed MCCFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC presenting as a well-defined, rapidly growing, asymptomatic, brightly violaceous nodule on the left cheek of a 71-year-old man. The patient developed a golf-ball sized subcutaneous mass in the left parotid (original biopsy site marked with blue ink, subcutaneous metastasis marked with arrow). Fine needle aspiration of the mass in the left parotid gland confirmed MCCFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2 cm red, nodular MCC with varied vessel patterns on the right upper arm of an 80-year-old manFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2 cm red, nodular MCC with varied vessel patterns on the right upper arm of an 80-year-old manFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC on the right posterior ankle of a 66-year-old African-American man, which presented as a subtle 1.5 cm subcutaneous nodule without overlying epidermal changes. This can often be confused with benign entities such as an epidermal cyst or a lipomaFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2x3 cm MCC lesion in a white man aged in his late 60s who had a history of taking immunosuppressive medication for psoriasis. The nodule was violaceous with central ulceration, tan crusting, and serous drainage. Note that ulceration is unusual in MCCTomtschik J et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2022; 15: e249288; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2x3 cm MCC lesion in a white man aged in his late 60s who had a history of taking immunosuppressive medication for psoriasis. The nodule was violaceous with central ulceration, tan crusting, and serous drainage. Note that ulceration is unusual in MCCTomtschik J et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2022; 15: e249288; used with permission [Citation ends].

Biopsy

Any non-tender nodule with non-specific morphology that is fast growing should be biopsied rather than monitored.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Skin biopsy confirms the diagnosis and provides prognostic information.

Ensure that the clinical size of the lesion is measured prior to biopsy as this has implications for the T-staging, prognosis, and recommended treatment pathway.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[42]Smith FO, Yue B, Marzban SS, et al. Both tumor depth and diameter are predictive of sentinel lymph node status and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2015 Sep 15;121(18):3252-60.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.29452

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26038193?tool=bestpractice.com

A punch, incisional, or excisional biopsy should be performed on any suspicious lesion.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer. 2008 Nov 1;113(9):2549-58.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.23874

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18798233?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Tetzlaff MT, Harms PW. Danger is only skin deep: aggressive epidermal carcinomas. An overview of the diagnosis, demographics, molecular-genetics, staging, prognostic biomarkers, and therapeutic advances in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2020 Jan;33(suppl 1):42-55.

https://www.modernpathology.org/article/S0893-3952(22)00718-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31676786?tool=bestpractice.com

The most appropriate method will depend on the size and location of the tumour.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) must be used in conjunction with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for confirmation of the diagnosis and to rule out histological mimics (most notably other small cell tumours, including basal cell carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, and small cell melanoma).[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Silk AW, Barker CA, Bhatia S, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jul;10(7):e004434.

https://jitc.bmj.com/content/10/7/e004434

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35902131?tool=bestpractice.com

[39]Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer. 2008 Nov 1;113(9):2549-58.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.23874

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18798233?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Tetzlaff MT, Harms PW. Danger is only skin deep: aggressive epidermal carcinomas. An overview of the diagnosis, demographics, molecular-genetics, staging, prognostic biomarkers, and therapeutic advances in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2020 Jan;33(suppl 1):42-55.

https://www.modernpathology.org/article/S0893-3952(22)00718-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31676786?tool=bestpractice.com

Staining that is positive for cytokeratin 20 (CK20) and negative for thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1) is usually considered sufficient to confirm the MCC diagnosis, although variations are sometimes reported.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

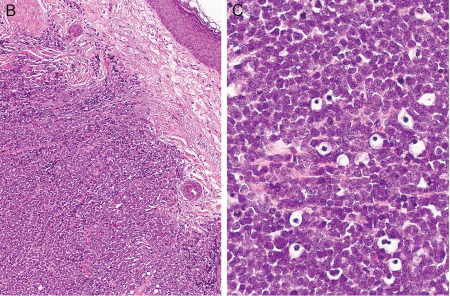

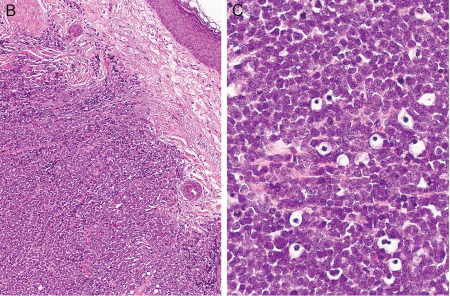

H&E typically shows a dermally-based tumour of small round blue cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, a 'salt and pepper' chromatin pattern, and high mitotic activity.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Spada F, Bossi P, Caracò C, et al; DELPHI Panel Members. Nationwide multidisciplinary consensus on the clinical management of Merkel cell carcinoma: a Delphi panel. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jun;10(6):e004742. [Erratum in: J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Sep;10(9):e004742corr1.]

https://jitc.bmj.com/content/10/6/e004742

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35701070?tool=bestpractice.com

[43]Tetzlaff MT, Harms PW. Danger is only skin deep: aggressive epidermal carcinomas. An overview of the diagnosis, demographics, molecular-genetics, staging, prognostic biomarkers, and therapeutic advances in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2020 Jan;33(suppl 1):42-55.

https://www.modernpathology.org/article/S0893-3952(22)00718-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31676786?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histological features of MCC from biopsy of a primary tumour. Image B shows small round blue cells and image C shows characteristic nuclei, finely granular and dusty 'salt and pepper' chromatin, and abundant mitotic figuresMauzo SH et al. J Clin Pathol 2016; 69: 382-90; used with permission [Citation ends].

Subsequent diagnostic work-up

Once the diagnosis of MCC is confirmed, consult with the multidisciplinary team.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical examination and initial imaging studies (if indicated) are used to make an initial determination of the clinical N-stage and M-stage, which then determines the recommended approach to pathological evaluation of lymph nodes.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Staging

Initial staging involves a complete examination of the patient's skin and palpation of lymph nodes, which may reveal clinical signs of metastatic disease.[2]Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Mar;58(3):375-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2335370

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18280333?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

[29]Silk AW, Barker CA, Bhatia S, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jul;10(7):e004434.

https://jitc.bmj.com/content/10/7/e004434

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35902131?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Becker JC, Beer AJ, DeTemple VK, et al. S2k guideline - Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin) - update 2022. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023 Mar;21(3):305-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddg.14930

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36929552?tool=bestpractice.com

Clinical size of the primary tumour lesion, as measured prior to biopsy, is needed for T-staging.[45]Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Mar;67(2):93-9.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.21388

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28094848?tool=bestpractice.com

MCC presents with a primary tumour without regional metastases in 65.4% of cases. However, it has a high risk of loco-regional metastasis, and presents with nodal and distant metastasis in 26.3% and 8.3% of patients, respectively.[10]Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 Oct;23(11):3564-71.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8881989

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27198511?tool=bestpractice.com

Cutaneous satellite or in-transit metastases present as smaller papules or nodules surrounding the primary tumour. In-transit metastases are defined as lesions that are discontinuous from the primary tumour, located between the primary tumour and the draining regional nodal basin or distal to the primary tumour site.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Regional lymph node metastases present as enlarged lymph nodes or masses in the draining nodal lymph node basin.

In addition, MCC can present with clinically detectable metastatic disease in a lymph node without a primary tumour (unknown primary MCC).[35]Tarantola TI, Vallow LA, Halyard MY, et al. Unknown primary Merkel cell carcinoma: 23 new cases and a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Mar;68(3):433-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23182060?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Deneve JL, Messina JL, Marzban SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012 Jul;19(7):2360-6.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4504007

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22271206?tool=bestpractice.com

[47]Chen KT, Papavasiliou P, Edwards K, et al. A better prognosis for Merkel cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin. Am J Surg. 2013 Nov;206(5):752-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23835211?tool=bestpractice.com

Around 11% of patients with MCC have no identifiable primary lesion.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

These patients have significantly higher survival rates compared with those who have a similar extent of disease but with a known primary lesion.[29]Silk AW, Barker CA, Bhatia S, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 Jul;10(7):e004434.

https://jitc.bmj.com/content/10/7/e004434

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35902131?tool=bestpractice.com

Histopathological confirmation of metastatic disease with biopsy is recommended.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Singh N, Alexander NA, Lachance K, et al. Clinical benefit of baseline imaging in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 584 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Feb;84(2):330-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7854967

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32707254?tool=bestpractice.com

A skin biopsy should be performed on suspected satellite/in-transit metastases.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or core biopsy should be performed on suspected lymph node metastases.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging

Imaging is recommended for all cases of MCC to evaluate for regional lymph node metastases and distant disease and for staging of the disease.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Becker JC, Beer AJ, DeTemple VK, et al. S2k guideline - Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin) - update 2022. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023 Mar;21(3):305-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddg.14930

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36929552?tool=bestpractice.com

This is because occult metastatic disease has been detected in 12% to 20% of patients who presented with no suspicious findings on history and examination.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[48]Singh N, Alexander NA, Lachance K, et al. Clinical benefit of baseline imaging in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 584 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Feb;84(2):330-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7854967

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32707254?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound of regional lymph nodes is recommended for patients with clinical stage I or II disease to evaluate for regional involvement.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Data indicate that whole-body fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) with fused axial imaging is the most reliable method for detecting occult metastatic MCC at baseline.[49]Belhocine T, Pierard GE, Frühling J, et al. Clinical added-value of 18FDG PET in neuroendocrine-Merkel cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2006 Aug;16(2):347-52.

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/or/16/2/347

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16820914?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Siva S, Byrne K, Seel M, et al. 18F-FDG PET provides high-impact and powerful prognostic stratification in the staging of Merkel cell carcinoma: a 15-year institutional experience. J Nucl Med. 2013 Aug;54(8):1223-9.

https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/54/8/1223

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23753187?tool=bestpractice.com

It is therefore recommended as the preferred cross-sectional imaging modality, if available, to assess local and distant disease.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

An acceptable alternative is CT with contrast of chest/abdomen/pelvis (and neck if the primary tumour is on the head/neck).[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Use MRI of the brain with or without contrast if there is clinical suspicion of brain metastases (e.g., if the patient has neurological symptoms).[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Imaging is also an important tool to evaluate for underlying, non-cutaneous, visceral neuroendocrine tumour mimics such as small cell lung cancer that may have metastasised to the dermis.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)

SLNB is recommended for any patient who presents without detectable metastatic disease and who is a candidate for surgery.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al. Recurrence and survival in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy for Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 153 patients from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011 Sep;18(9):2529-37.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4117701

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21431988?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al. Five hundred patients with Merkel cell carcinoma evaluated at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2011 Sep;254(3):465-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21865945?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Tarantola TI, Vallow LA, Halyard MY, et al. Unknown primary Merkel cell carcinoma: 23 new cases and a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Mar;68(3):433-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23182060?tool=bestpractice.com

[42]Smith FO, Yue B, Marzban SS, et al. Both tumor depth and diameter are predictive of sentinel lymph node status and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2015 Sep 15;121(18):3252-60.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.29452

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26038193?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Becker JC, Beer AJ, DeTemple VK, et al. S2k guideline - Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin) - update 2022. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023 Mar;21(3):305-20.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ddg.14930

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36929552?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]Schwartz JL, Griffith KA, Lowe L, et al. Features predicting sentinel lymph node positivity in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Mar 10;29(8):1036-41.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4136

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21300936?tool=bestpractice.com

It is performed prior to, or at the time of, excision of the primary tumour.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

SLNB is the most reliable tool to identify subclinical metastatic disease in the regional nodal basin.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

SLNB has been demonstrated to detect lymph node spread in up to one third of patients who would have otherwise been staged as node-negative.[52]Gupta SG, Wang LC, Peñas PF, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: the Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2006 Jun;142(6):685-90.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/405972

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16785370?tool=bestpractice.com

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) MCC guideline notes that false-negative SLNBs can be seen in patients who are immunocompromised or who have tumours localised in the head, neck, or midline trunk region and/or with aberrant lymph node drainage.[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Emerging tests

Serum testing of antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is available in some centres in the US. US guidelines state that it can be helpful if available, whereas European guidelines state that further prospective validation is required.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[19]Lugowska I, Becker JC, Ascierto PA, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Merkel-cell carcinoma: ESMO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2024 May;9(5):102977.

https://www.esmoopen.com/article/S2059-7029(24)00745-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38796285?tool=bestpractice.com

Virus-positive MCC is one of two subtypes of the disease and carries a better prognosis than UV-induced MCC.[7]Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al; the European Dermatology Forum (EDF), the European Association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO), and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline - update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022 Aug:171:203-31.

https://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(22)00253-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35732101?tool=bestpractice.com

A proportion of patients with MCC caused by MCPyV develop antibodies to MCPyV oncoproteins.[53]Park SY, Doolittle-Amieva C, Moshiri Y, et al. How we treat Merkel cell carcinoma: within and beyond current guidelines. Future Oncol. 2021 Apr;17(11):1363-77.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2217/fon-2020-1036

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33511866?tool=bestpractice.com

The baseline AMERK test is undertaken within 3 months of initial treatment.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

In patients who are seropositive, antibody titres can be monitored to detect changes in MCC disease burden as a rising titre may be an early indicator of recurrence.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[53]Park SY, Doolittle-Amieva C, Moshiri Y, et al. How we treat Merkel cell carcinoma: within and beyond current guidelines. Future Oncol. 2021 Apr;17(11):1363-77.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2217/fon-2020-1036

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33511866?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Paulson KG, Lewis CW, Redman MW, et al. Viral oncoprotein antibodies as a marker for recurrence of Merkel cell carcinoma: a prospective validation study. Cancer. 2017 Apr 15;123(8):1464-74.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.30475

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27925665?tool=bestpractice.com

More intensive follow-up is indicated for seronegative patients as MCPyV-negative patients have a worse prognosis.[3]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Merkel cell carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) analysis, which measures circulating cell-free DNA from tumour cells, is an emerging blood test for molecular disease monitoring of different cancers, including MCC.[55]Yeakel J, Kannan A, Rattigan NH, et al. Bespoke circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker for treatment response in a refractory Merkel cell carcinoma patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2021 Dec;18:94-8.

https://www.jaadcasereports.org/article/S2352-5126(21)00778-5/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34869814?tool=bestpractice.com

[56]Prakash V, Gao L, Park SJ. Evolving applications of circulating tumor DNA in Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Jan 18;15(3):609.

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/15/3/609

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36765567?tool=bestpractice.com

Additional studies are needed to further define its role in MCC.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A rapidly-growing MCC on the right cheek of a 64-year-old man, which started as a small erythematous cyst-like papule then developed within a few months into a larger, violaceous nodule with associated pruritusFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A rapidly-growing MCC on the right cheek of a 64-year-old man, which started as a small erythematous cyst-like papule then developed within a few months into a larger, violaceous nodule with associated pruritusFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC on the left lower lip of a 68-year-old man. The asymptomatic tumour is an ill-defined reddish-pink, scaly plaque blurring the lower vermillion of the lipFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC on the left lower lip of a 68-year-old man. The asymptomatic tumour is an ill-defined reddish-pink, scaly plaque blurring the lower vermillion of the lipFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Primary MCC on the right frontal scalp (asterisk) of a 73-year-old man, with a biopsy scar of an in-transit metastasis (arrow). The primary tumor initially presented as an asymptomatic, fast-growing subcutaneous nodule that was misdiagnosed as an epidermoid cystFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Primary MCC on the right frontal scalp (asterisk) of a 73-year-old man, with a biopsy scar of an in-transit metastasis (arrow). The primary tumor initially presented as an asymptomatic, fast-growing subcutaneous nodule that was misdiagnosed as an epidermoid cystFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC presenting as a well-defined, rapidly growing, asymptomatic, brightly violaceous nodule on the left cheek of a 71-year-old man. The patient developed a golf-ball sized subcutaneous mass in the left parotid (original biopsy site marked with blue ink, subcutaneous metastasis marked with arrow). Fine needle aspiration of the mass in the left parotid gland confirmed MCCFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: MCC presenting as a well-defined, rapidly growing, asymptomatic, brightly violaceous nodule on the left cheek of a 71-year-old man. The patient developed a golf-ball sized subcutaneous mass in the left parotid (original biopsy site marked with blue ink, subcutaneous metastasis marked with arrow). Fine needle aspiration of the mass in the left parotid gland confirmed MCCFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2 cm red, nodular MCC with varied vessel patterns on the right upper arm of an 80-year-old manFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2 cm red, nodular MCC with varied vessel patterns on the right upper arm of an 80-year-old manFrom the collection of Dr Kelly Harms and Dr Alison Lee, University of Michigan; used with patient consent [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2x3 cm MCC lesion in a white man aged in his late 60s who had a history of taking immunosuppressive medication for psoriasis. The nodule was violaceous with central ulceration, tan crusting, and serous drainage. Note that ulceration is unusual in MCCTomtschik J et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2022; 15: e249288; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A 2x3 cm MCC lesion in a white man aged in his late 60s who had a history of taking immunosuppressive medication for psoriasis. The nodule was violaceous with central ulceration, tan crusting, and serous drainage. Note that ulceration is unusual in MCCTomtschik J et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2022; 15: e249288; used with permission [Citation ends].