Recommendations

Urgent

Suspect HAP in a patient with symptoms and signs of a lower respiratory tract infection (e.g., cough, fever, chest pain, malaise) that develops 48 hours or more after hospital admission and that was not incubating at admission.[3][7]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia with symptoms and signs that start at any point after hospital admission, see Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Consider all patients with cough, fever, or other suggestive symptoms to have COVID-19 until proven otherwise. Pneumonia due to COVID-19 is not covered in this topic.

For patients with symptoms and signs consistent with bacterial pneumonia (not secondary to COVID-19) that start on days 1 or 2 after hospital admission, see Community-acquired pneumonia (non-Covid-19).

For patients with suspected pneumonia of any cause developing after endotracheal intubation, consult a senior specialist in critical care.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia is not covered in this topic.

Be aware of atypical presentations of HAP, such as in a patient with suspected sepsis or delirium.

Think 'Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[28][29][30] See Sepsis in adults.

Use a systematic approach, alongside your clinical judgement, for assessment; urgently consult a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor in the UK) if you suspect sepsis.[28][30][31][32]

Refer to local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution for assessment and management of the patient with suspected sepsis.

Pneumonia is one of the main sources of sepsis.[33]

Request a chest x-ray in all patients with suspected HAP.[3][7]

New and/or persistent shadowing on chest x-ray, which is otherwise unexplained, plus at least two of the following confirms the diagnosis:[1]

Fever >38ºC (>100ºF)

Leukocytosis (WBC >10 x 109/L) or leucopenia (WBC <4 x 109/L)

Purulent sputum

Decline in oxygenation.

Measure oxygen saturations and order blood tests in all patients with suspected HAP including:[34]

Full blood count: may show leukocytosis (WBC >10 x 109/L) or leucopenia (WBC < 4 x 109/L)[1]

Blood gas (in practice, venous blood gas is preferable to arterial blood gas). May show:

Hypoxia

Respiratory alkalosis

Metabolic acidosis (due to hypotension, reduced tissue perfusion, acute kidney injury)

Raised lactate levels.

C-reactive protein: elevated in nosocomial pneumonia

Liver and renal function tests: may show abnormal values, particularly if there is underlying or associated pathology.[34]

Key Recommendations

Consider a chest CT scan if the chest x-ray:

Is of poor quality[6]

Shows ill-defined consolidation[6]

Shows ‘complicated’ pneumonia or atypical changes, such as cavitation, multifocal consolidation pattern, or pleural effusion.[35] See Differentials section.

Consider a chest ultrasound if pleural effusion is seen on chest x-ray (with or without guided aspiration and chest CT) to help make an alternative diagnosis.

Shows complex findings in patients who do not respond to treatment.[36]

Send a sputum sample for culture and testing, ideally before starting antibiotics.[7][34]

Take other non-invasive respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal swab or tracheal aspirate) for culture if the patient cannot produce sputum.[6][7]

Consider:

Urine antigen tests if legionella or pneumococcal pneumonia is suspected.[34]

PCR/serological tests if respiratory viruses or atypical pathogens are strongly suspected.[34]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, order a nucleic acid amplification test, such as real-time PCR, for SARS-CoV-2 in any patient with suspected infection whenever possible.[37][38] See Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Suspect HAP in a patient with symptoms and signs of a lower respiratory tract infection that develops 48 hours or more after hospital admission and that was not incubating at admission.[3]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia with symptoms and signs that start at any point after hospital admission, see Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Consider all patients with cough, fever, or other suggestive symptoms to have COVID-19 until proven otherwise.

Patients with bacterial pneumonia are more likely to have rapid development of symptoms and purulent sputum. They are less likely to have myalgia, anosmia, or pleuritic pain.[39]

Pneumonia due to COVID-19 is not covered in this topic.

For patients with symptoms and signs consistent with bacterial pneumonia (not secondary to COVID-19) that start on days 1 or 2 after hospital admission, see Community-acquired pneumonia (non-Covid-19).

For patients with suspected pneumonia of any cause developing after endotracheal intubation, consult a senior specialist in critical care.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia is not covered in this topic.

A new and/or persistent shadowing (consolidation) on chest x-ray, which is otherwise unexplained, plus at least two of the following confirms the diagnosis:[1]

Fever >38ºC (>100ºF)

Leukocytosis (WBC >10 x 109/L) or leucopenia (WBC <4 x 109/L)

Purulent sputum

Decline in oxygenation.

Other symptoms may include:

Cough

Dyspnoea

Chest pain

Malaise

Anorexia.

Be aware of atypical presentations of HAP, such as in a patient with suspected sepsis or delirium.

Practical tip

Think 'Could this be sepsis?' based on acute deterioration in a patient in whom there is clinical evidence or strong suspicion of infection.[28][29][30]

The patient may present with non-specific or non-localised symptoms (e.g., acutely unwell with a normal temperature) or there may be severe signs with evidence of multi-organ dysfunction and shock.[28][29][30]

Remember that sepsis represents the severe, life-threatening end of infection.[40]

Pneumonia is one of the main sources of sepsis.[33]

Use a systematic approach (e.g., NEWS2), alongside your clinical judgement, to assess the risk of deterioration due to sepsis.[28][29][31][41] Consult local guidelines for the recommended approach at your institution.

In the UK, arrange urgent review by a senior clinical decision-maker (e.g., ST4 level doctor) if you suspect sepsis:[32]

Within 30 minutes for a patient who is critically ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 7 or more, evidence of septic shock, or other significant clinical concerns).

Within 1 hour for a patient who is severely ill (e.g., NEWS2 score of 5 or 6).

Follow your local protocol for investigation and treatment of all patients with suspected sepsis. Start treatment promptly. Determine urgency of treatment according to likelihood of infection and severity of illness, or according to your local protocol.[32]

See Sepsis in adults.

Practical tip

Do not confuse HAP with a hospital-acquired lower respiratory tract infection, which is non-pneumonic (no consolidation on chest x-ray).

Check when the patient was admitted to hospital.

HAP is pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after hospital admission and that was not incubating at admission.[3][7]

Assess the risk of pneumonia due to multidrug-resistant bacteria. There is a higher risk of resistance in patients with:[7]

Symptoms or signs starting more than 5 days after hospital admission

Relevant comorbidity, such as severe lung disease or immunosuppression

Recent use of broad-spectrum antibiotic

Colonisation with multidrug-resistant bacteria

Recent contact with health or social care settings before current admission.

Consider other risk factors that predispose a patient to HAP such as:

Intubation and mechanical ventilation; mechanical ventilation is the most significant risk factor for HAP (ventilator-associated pneumonia is not covered in this topic)[19][20]

Acid-suppression drugs[21]

Aspiration[19]

Depressed consciousness[20]

Practical tip

Consider dysphagia as a potential cause of HAP, particularly in frail patients and those with neurological disorders (including cognitive impairment). Consider referring these patients to a speech and language therapist. Managing swallowing problems reduces the subsequent risk of aspiration pneumonia.[42]

Carry out a thorough examination, particularly of the cardiorespiratory system, to identify features consistent with HAP.

Check for:

Fever (>38ºC [>100ºF])

Raised respiratory rate

Tachycardia

Asymmetrical expansion of the chest

May be a suppressed motion on the affected side

Diminished lung resonance

May be dull on the side of the consolidation

Abnormal findings on auscultation (none, some, or all of the following may be present):

Crackles or rhonchi

Aegophony: a change in the sound of a patient's voice (e.g., an 'eee' sound is heard as 'aaa')

Whisper pectoriloquy: a whisper is heard clearly and loudly while auscultating over the affected part of the lung

Bronchial breathing: harsh breath sounds with a gap between the inspiratory and expiratory phases

Increased vocal resonance: more audible vocal sounds (e.g., while the patient says “99”).

Focus in addition on other areas (e.g., throat, legs) if the presentation suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as an upper respiratory tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism.

Order a chest x-ray in all patients with suspected HAP as soon as possible.[6]

New and/or persistent shadowing (consolidation) on chest x-ray, which is otherwise unexplained, plus the presence of at least two clinical features (purulent sputum, decline in oxygenation, fever >38ºC [>100ºF], leukocytosis [WBC >10 x 109/L], or leucopenia [WBC <4 x 109/L]) confirms the diagnosis.[1]

In practice, posterior-anterior and lateral views are preferred over anterior-posterior views. Compare with previous chest x-rays if available.

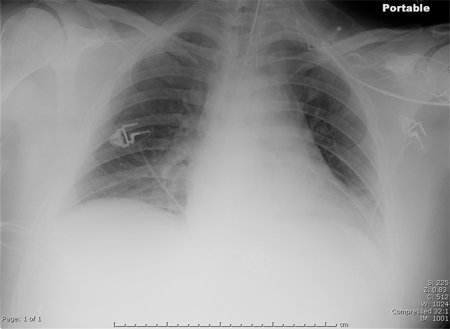

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Portable chest x-ray of a patient with HAP. Note the obscured left hemidiaphragm due to a left lower lobe opacity and an obscured heart border due to a left upper lobe or lingular opacityConsent obtained at University of Louisville, Louisville, KY [Citation ends].

Reassess the patient if the chest x-ray shows no consolidation.[6]

Consider a chest CT scan:

When there is diagnostic doubt: for example, if the chest x-ray is of poor quality or there is an ill-defined consolidation[6]

In patients with a complex chest x-ray who do not respond to treatment (to guide treatment)[36]

When the chest x-ray shows ‘complicated’ pneumonia or atypical changes, such as cavitation, multifocal consolidation pattern, or pleural effusion.[35]

Consider additional imaging investigations such as chest ultrasound. For example, pleural effusion seen on chest x-ray may prompt you to perform a chest ultrasound (with or without guided aspiration and chest CT) to help make an alternative diagnosis. See the Differentials section.

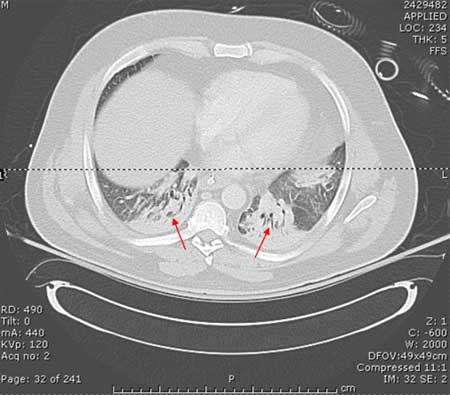

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan showing bi-basilar opacities in a patient with HAPConsent obtained at University of Louisville, Louisville, KY [Citation ends].

Chest x-ray findings | Further imaging | Consider alternative diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

Cavitation | Chest CT scan |

|

Multifocal consolidation (note that it is the multifocal nature, not the consolidation, that is the distinguishing feature) | Chest CT scan |

|

Pleural effusion | Chest ultrasound +/- guided aspiration +/- Chest CT-scan |

|

Practical tip

‘Complicated’ pneumonia refers to pneumonia that is complicated by the presence of parapneumonic effusion (an exudative pleural effusion associated with pulmonary infection), empyema (pus in the pleural space), abscess, pneumothorax, necrotising pneumonia (pneumonia associated with cavitation), or bronchopleural fistula.

Around 40% of people who are hospitalised for pneumonia develop parapneumonic effusion.[43] Empyema is a type of pleural effusion that is difficult to distinguish from a parapneumonic effusion on chest x-ray.

Findings on a CT scan suggestive of a parapneumonic effusion (as opposed to empyema) include:[44]

Usually small volume

Normal meniscus sign

Dependent

No loculation.

‘Split pleura sign’ is not typical and is more specific for empyema.

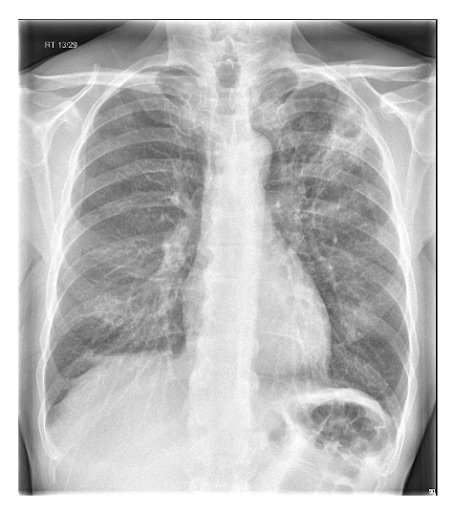

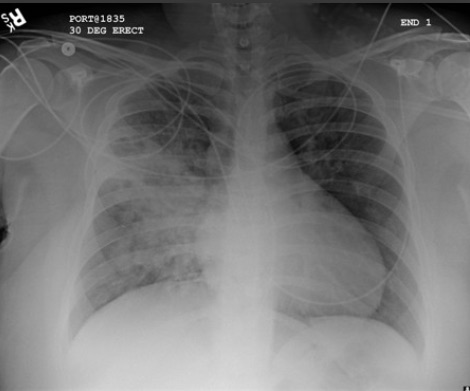

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing left upper lobe cavitating pneumoniaFrom the collection of Dr Jonathan Bennett; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left-sided pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr R Light; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left-sided pleural effusionFrom the collection of Dr R Light; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Increased opacification of the right perihilar region and superior segment of the right lower and upper lobes consistent with worsening aspiration pneumoniaFrom the collection of Dr Roy Hammond, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Increased opacification of the right perihilar region and superior segment of the right lower and upper lobes consistent with worsening aspiration pneumoniaFrom the collection of Dr Roy Hammond, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

The clinico-radiological features of HAP and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are very similar. Due to a lack of specific guidance on general investigations for patients with HAP, the following recommendations have largely been extrapolated from the British Thoracic Society guidelines on CAP.[34]

Oxygen saturations

Measure oxygen saturations in all patients with suspected HAP.[34]

Blood tests

Take bloods in all patients with suspected HAP and request the following tests:

Full blood count

Patients with HAP may have leukocytosis (WBC >10 x 109/L) or leucopenia (WBC <4 x 109/L).[1]

Blood gases (in practice, venous blood gas is preferable to arterial blood gas). May show:

Hypoxia

Respiratory alkalosis

Metabolic acidosis (due to hypotension, reduced tissue perfusion, or acute kidney injury)

Raised lactate levels.

C-reactive protein (CRP)

Helps rule out other acute respiratory illnesses and provides a baseline measure.

Elevated in people with nosocomial pneumonia.

High levels of CRP do not necessarily indicate that pneumonia is bacterial or SARS-CoV-2, but low CRP levels make a secondary bacterial infection less likely.[45]

Renal and liver function tests (LFTs)

Helps determine the severity of illness and can indicate the presence of multiorgan dysfunction.

May show abnormal values, particularly if there is underlying or associated pathology.[34] Pneumonia can cause renal impairment and abnormal LFTs, although this is more likely in someone with pre-existing renal or liver disease.

Practical tip

Obtaining a blood gas while the patient is not yet receiving supplemental oxygen provides a more accurate reflection of the oxygenation status, but should not delay supplemental oxygen in an unstable patient.

Consider ordering serum procalcitonin. Although currently excluded from key guidelines, baseline procalcitonin is increasingly being used in critical care settings and in the emergency department to guide decisions on antibiotic treatment in patients with highly suspected sepsis and in those with suspected bacterial infection.[41][46][47][48][49]

Elevated procalcitonin is correlated with bacterial pneumonia whereas lower values are correlated with viral and atypical pneumonia. Procalcitonin is typically markedly elevated in people with pneumococcal pneumonia.[50][51]

Procalcitonin is a peptide precursor of calcitonin, which is responsible for calcium homeostasis.

Thoracocentesis

Arrange an early thoracocentesis in all patients with pleural effusion as this can reveal an infected pleural space consistent with a parapneumonic effusion.[34]

Aspiration of pus and/or a positive Gram stain of pleural fluid indicates an empyema.

Drain the pleural fluid in patients with an empyema or clear pleural fluid with pH <7.2.[34]

The clinico-radiological features of HAP and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) are very similar. Due to a lack of specific guidance on microbiological investigations for patients with HAP, the following recommendations have largely been extrapolated from the British Thoracic Society guidelines on CAP.[34]

Sputum and other non-invasive respiratory samples for culture

Send a sample (sputum, nasopharyngeal swab, or tracheal aspirate) for microbiological testing.[7]

Microbiological diagnosis allows for the selection of pathogen-targeted antibiotics, reducing use of ineffective empirical antibiotics or unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Early-onset HAP (<5 days after admission to hospital) is often caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae.[7]

Late-onset HAP (>5 days after admission to hospital) is usually caused by microorganisms that are acquired in hospital, most commonly MRSA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other non-pseudomonal gram-negative bacteria.[7]

Take sputum samples for culture first, ideally before antibiotics are started.[6][7]

The patient needs to be able to produce a good specimen, which may not be the case in patients with HAP.[52]

Take other non-invasive respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal swab or tracheal aspirate) if the patient cannot produce sputum.[6][7]

Practical tip

Positive cultures need to be correlated clinically. They may be false positives showing evidence of colonisation of the trachea or false negatives due to prior antimicrobial treatment.

Urine antigen testing

Consider legionella and pneumococcal urine antigen tests if legionella or pneumococcal pneumonia is suspected.[34]

Legionella species and pneumococcus are less commonly associated with HAP than with CAP.[34]

PCR and serological tests

Consider polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or serological investigations of sputum, nasopharyngeal swab, or tracheal aspirate if there is a strong suspicion of respiratory viruses (influenza A and B, parainfluenza 1–3, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus) or atypical pathogens.[34]

Viruses and atypical pathogens are less commonly associated with HAP than with CAP.[34]

PCR (if available) is preferred over serological investigations.[34]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, order a nucleic acid amplification test, such as real-time PCR, for SARS-CoV-2 in any patient with suspected infection whenever possible.[37][38] See Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer