History and exam

Key diagnostic factors

Other diagnostic factors

common

uterine mass, fixed uterus, or adnexal mass indicating extra-uterine disease

A bi-manual examination gives an idea of the uterine size and also evaluates for adnexal mass.

uncommon

abnormal menstruation or vaginal bleeding in a pre-menopausal woman

pain (abdominal or pelvic) and weight loss

May suggest extra-uterine disease. Rarely reported at initial presentation.

symptoms of metastatic disease

Possible symptoms include abdominal distension, fatigue, diarrhoea, nausea or vomiting, persistent cough, shortness of breath, swelling, or new-onset neurological symptoms.

Symptoms of metastases at initial presentation are rare.

signs of metastatic disease

Enlarged lymph nodes may be a sign of metastatic spread. Nodal metastases are typically not diagnosed until surgery.

Signs of metastases at initial presentation are rare.

Risk factors

strong

overweight and obesity

The most important aetiological factor. Overweight and obesity are present in approximately 80% and 50% of patients, respectively.[52] Overweight women (BMI 25 to <30) are twice as likely to develop the disease compared with women with BMI <25. Obesity (BMI ≥30) triples the risk.[53][54][55]

Obesity causes insulin resistance, androgen excess, anovulation, and chronic progesterone deficiency.[56]

age >50 years

endometrial hyperplasia

Many of the risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer are the same.

Endometrial hyperplasia is classified as non-atypical (simple and complex) and atypical (simple and complex).[1]

Atypical endometrial hyperplasia is a risk factor for development of endometrial cancer; post-menopausal women should undergo hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy if not medically contraindicated.[31][32][33][58]

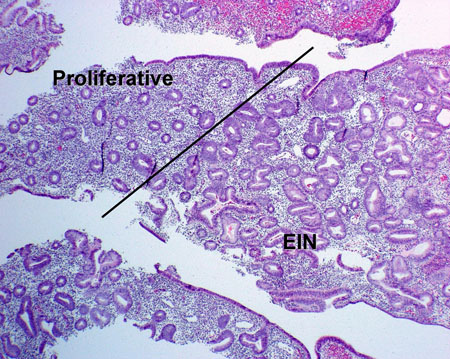

Complex hyperplasia with cytological atypia is termed endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN).[32][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Epithelial in situ neoplasia arising in proliferative endometrium (photomicrograph, haematoxylin and eosin stain)From the collection of George Mutter MD, Division of Women's and Perinatal Pathology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School [Citation ends]. Loss of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) expression is highly specific for endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.[59]

Loss of B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) expression is highly specific for endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.[59]

Endometrial cancer may be present in up to 42.6% of cases when the initial diagnosis is hyperplasia with atypia.[60] The odds ratio of co-existent cancer in the presence of endometrial hyperplasia is 11.[61]

unopposed endogenous oestrogen

unopposed exogenous oestrogen

Exogenous oestrogen therapy (e.g., hormone replacement therapy) in pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women is associated with endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer.[31][34][35] Compared with non-use, relative risk of endometrial cancer is 2-10 with oestrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (depending on duration of use).[34][35]

In population-based cohort studies, long-term oral contraceptive use was associated with reduced risk of endometrial cancer, particularly in women who were obese, physically inactive, or smokers.[64][65]

tamoxifen use (post-menopausal women)

Tamoxifen has tissue-specific, pro-oestrogenic effects and is associated with both benign and malignant uterine tumours, particularly sarcomas.[66]

There is a greater than 7-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer in women with breast cancer exposed to tamoxifen, and in these patients clear cell carcinoma is more common.[67][68]

Tamoxifen use in pre-menopausal women is not associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer.[69]

insulin resistance

family history of endometrial or colorectal cancer

Women with a first-degree family history of endometrial cancer or colorectal cancer appear to be at higher risk of developing endometrial cancer than those without a family history.[39][73]

Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer) is a familial cancer syndrome associated with an increased lifetime risk of endometrial cancer (35% to 54%) compared with the general population (3.1%).[74] Genetic risk assessment is recommended for patients with a strong family history of endometrial or colorectal cancer.[74][75]

Lynch syndrome genes do not fully explain familial endometrial cancer risk.[73]

family history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer

Family history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer increases the risk for endometrial cancer.[38]

family history of Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer)

Lynch syndrome is associated with an increased lifetime risk of endometrial cancer (35% to 54%) compared with the general population (3.1%).[74]

Around 9% of endometrial cancer patients aged <50 years carry germline Lynch syndrome-associated mutations.[41] These patients are typically less overweight.

Genetic testing for a specific pathogenic variant can be carried out, if known; germline multigene panel testing is recommended if the variant is unknown.[74]

Immunohistochemical staining for mismatch-repair (MMR) proteins or testing for microsatellite instability should be used to screen tumour tissue. Germline testing for a deleterious mutation related to MMR gene expression is required to establish a diagnosis of Lynch syndrome.[76][77]

family history of PTEN syndromes

polycystic ovary syndrome

radiotherapy

Despite a strong association, radiotherapy for another malignancy is a rare cause of secondary endometrial cancer.[81]

weak

diet

Diet may play a role in endometrial cancer risk by modulating chronic inflammation. Western dietary patterns and an elevated dietary inflammatory index may be associated with a higher risk of endometrial cancer.[84][85]

An inverse association has been shown between dietary fibre consumption and risk of endometrial cancer.[86]

nulliparity and infertility

Progestins and pregnancy are protective.[43]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer