Diagnosis is based on the presence of well-defined criteria that help distinguish MM from other plasma cell neoplasms and B-cell malignancies associated with paraprotein (M-protein) production.[3]Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48.

https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/174646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25439696?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Rajkumar SV. Updated diagnostic criteria and staging system for multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e418-23.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_159009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27249749?tool=bestpractice.com

See Classification.

Initial diagnostic work-up includes a full history and physical examination with key diagnostic tests providing definitive diagnosis.[44]Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. Ann Oncol. 2021 Mar;32(3):309-22.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43169-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33549387?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

History and clinical features

Family history of lymphohaematopoietic cancer (particularly MM), male sex, black ethnicity, and exposure to ionising radiation or petroleum products are associated with a higher risk for MM.[9]National Cancer Institute: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: myeloma. 2023 [internet publication].

https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html

[11]Schinasi LH, Brown EE, Camp NJ, et al. Multiple myeloma and family history of lymphohaematopoietic cancers: results from the International Multiple Myeloma Consortium. Br J Haematol. 2016 Oct;175(1):87-101.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.14199

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27330041?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Bourguet CC, Grufferman S, Delzell E, et al. Multiple myeloma and family history of cancer: a case-control study. Cancer. 1985 Oct 15;56(8):2133-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4027940?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Cardis E, Vrijheid M, Blettner M, et al. The 15-country collaborative study of cancer risk among radiation workers in the nuclear industry: estimates of radiation-related cancer risks. Radiat Res. 2007 Apr;167(4):396-416.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17388693?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]Torres A, Giralt M, Raichs A. Coexistence of chronic benzol contacts and multiple plasmacytoma: presentation of 2 cases [in Spanish]. Sangre (Barc). 1970;15(2):275-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5431825?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Aksoy M, Erdem S, Dincol G, et al. Clinical observations showing the role of some factors in the etiology of multiple myeloma: a study in 7 patients. Acta Haematol. 1984;71(2):116-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6421049?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Bergsagel DE, Wong O, Bergsagel PL, et al. Benzene and multiple myeloma: appraisal of the scientific evidence. Blood. 1999 Aug 15;94(4):1174-82.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/94/4/1174/249672/Benzene-and-Multiple-Myeloma-Appraisal-of-the

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10438704?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Stenehjem JS, Kjærheim K, Bråtveit M, et al. Benzene exposure and risk of lymphohaematopoietic cancers in 25,000 offshore oil industry workers. Br J Cancer. 2015 Apr 28;112(9):1603-12.

https://www.nature.com/articles/bjc2015108

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25867262?tool=bestpractice.com

MM is preceded by the asymptomatic premalignant disorder monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).

Initial symptoms of MM are usually non-specific (e.g., fatigue, bone pain) and are a result of the end-organ damage caused by myeloma cell infiltration and/or the associated paraproteinaemia. Bone pain (typically localised to the back) and anaemia are the most common presenting features, affecting 60% to 70% of patients.[5]Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: review of 869 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975 Jan;50(1):29-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1110582?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Jan;78(1):21-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12528874?tool=bestpractice.com

Other features include renal insufficiency, hypercalcaemia, and symptoms associated with infection.[5]Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: review of 869 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975 Jan;50(1):29-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1110582?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Jan;78(1):21-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12528874?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Blimark C, Holmberg E, Mellqvist UH, et al. Multiple myeloma and infections: a population-based study on 9253 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2015 Jan;100(1):107-13.

https://haematologica.org/article/view/7239

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25344526?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial laboratory work-up

Initial tests to order include a full blood count with differential and platelet counts, peripheral blood smear, serum urea, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes (including calcium), serum uric acid, liver function tests (LFTs), serum albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP), serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum beta2-microglobulin, and N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) or BNP (if NT-proBNP is unavailable).[44]Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. Ann Oncol. 2021 Mar;32(3):309-22.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43169-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33549387?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

These baseline laboratory tests can help guide diagnosis (e.g., by assessing end-organ damage) and inform prognostication and risk stratification.

Diagnostic tests

Tests used to establish a diagnosis include:[3]Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48.

https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/174646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25439696?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Rajkumar SV. Updated diagnostic criteria and staging system for multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e418-23.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_159009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27249749?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. Ann Oncol. 2021 Mar;32(3):309-22.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43169-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33549387?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myeloma: diagnosis and management. Oct 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng35

[47]Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jun;20(6):e302-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31162104?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum quantitative immunoglobulins

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis

Serum and urine immunofixation

Serum free light-chain assay

Imaging studies (e.g., whole-body imaging with low-dose computed tomography [CT] scan, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/CT [FDG-PET/CT], or in some cases magnetic resonance imaging [MRI])

Bone marrow evaluation

The vast majority of patients with MM present with an M-protein in the serum and/or urine (on electrophoresis or immunofixation). However, an M-protein is not detectable in 1% to 5% of patients. These patients are defined as having non-secretory MM.[6]Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003 Jan;78(1):21-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12528874?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]Drayson M, Tang LX, Drew R, et al. Serum free light-chain measurements for identifying and monitoring patients with nonsecretory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001 May 1;97(9):2900-2.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/97/9/2900/130347/Serum-free-light-chain-measurements-for

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11313287?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Kumar SK, Mikhael JR, Buadi FK, et al. Management of newly diagnosed symptomatic multiple myeloma: updated Mayo Stratification of Myeloma and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) consensus guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Dec;84(12):1095-110.

https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(11)60296-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19955246?tool=bestpractice.com

With the availability of the serum free light-chain assay, non-secretory as well as oligosecretory MM can be easily diagnosed.[48]Drayson M, Tang LX, Drew R, et al. Serum free light-chain measurements for identifying and monitoring patients with nonsecretory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001 May 1;97(9):2900-2.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/97/9/2900/130347/Serum-free-light-chain-measurements-for

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11313287?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Dispenzieri A, Kyle R, Merlini G, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for serum-free light chain analysis in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Leukemia. 2009 Feb;23(2):215-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19020545?tool=bestpractice.com

An M-protein is sometimes seen on serum protein electrophoresis in asymptomatic patients because of increased globulin fractions.

Mass spectrometry may be used as an alternative to immunofixation for the detection of M-proteins.[51]Murray DL, Puig N, Kristinsson S, et al. Mass spectrometry for the evaluation of monoclonal proteins in multiple myeloma and related disorders: an International Myeloma Working Group Mass Spectrometry Committee Report. Blood Cancer J. 2021 Feb 1;11(2):24.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41408-021-00408-4

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33563895?tool=bestpractice.com

Mass spectrometry is more sensitive than immunofixation, and can also assist in distinguishing between therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (administered to a patient) and endogenous M-proteins.[52]Zajec M, Jacobs JFM, Groenen PJTA, et al. Development of a targeted mass-spectrometry serum assay to quantify M-protein in the presence of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. J Proteome Res. 2018 Mar 2;17(3):1326-33.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29424538?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A: serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) of normal serum. B: SPEP of multiple myeloma serum showing a monoclonal immunoglobulin (M-protein) in the gamma region. C: densitometry tracing of normal serum (A) showing the 5 zones of the high resolution agarose electrophoresis. D: densitometry tracing of multiple myeloma serum (B) showing a monoclonal spike (M spike)Courtesy of Dr M Murali and the Clinical Immunology Laboratory, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

Imaging

Imaging to assess bone disease is essential for diagnosis and guiding treatment, and should be performed in all patients with suspected MM.[3]Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48.

https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/174646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25439696?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Rajkumar SV. Updated diagnostic criteria and staging system for multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e418-23.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_159009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27249749?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myeloma: diagnosis and management. Oct 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng35

[47]Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jun;20(6):e302-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31162104?tool=bestpractice.com

Whole-body low-dose CT or FDG-PET/CT is recommended for the initial diagnostic work-up for MM.[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myeloma: diagnosis and management. Oct 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng35

[47]Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jun;20(6):e302-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31162104?tool=bestpractice.com

Whole-body MRI should be considered if CT or FDG-PET/CT is negative or inconclusive, and suspicion remains high for MM.[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myeloma: diagnosis and management. Oct 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng35

[47]Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jun;20(6):e302-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31162104?tool=bestpractice.com

Conventional skeletal survey (radiography) is less sensitive at detecting osteolytic lesions compared with CT, FDG-PET/CT, and MRI, but it may be considered if these advanced imaging modalities are not available.[47]Hillengass J, Usmani S, Rajkumar SV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus recommendations on imaging in monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jun;20(6):e302-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31162104?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Terpos E, Kleber M, Engelhardt M, et al; European Myeloma Network. European Myeloma Network guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma-related complications. Haematologica. 2015 Oct;100(10):1254-66.

https://haematologica.org/article/view/7519

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26432383?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Hillengass J, Moulopoulos LA, Delorme S, et al. Whole-body computed tomography versus conventional skeletal survey in patients with multiple myeloma: a study of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood Cancer J. 2017 Aug 25;7(8):e599.

https://www.nature.com/articles/bcj201778

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28841211?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Walker R, Barlogie B, Haessler J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in multiple myeloma: diagnostic and clinical implications. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Mar 20;25(9):1121-8.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5803

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17296972?tool=bestpractice.com

MRI can detect focal lesions and bone marrow infiltration. It has prognostic value in asymptomatic patients because the presence of small focal lesions (i.e., <5 mm) in these patients is a strong predictor of progression to symptomatic MM.[56]Hillengass J, Fechtner K, Weber MA, et al. Prognostic significance of focal lesions in whole-body magnetic resonance imaging in patients with asymptomatic multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Mar 20;28(9):1606-10.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5356

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20177023?tool=bestpractice.com

FDG-PET/CT and MRI are particularly useful during treatment follow-up as they can detect residual focal lesions and inform prognosis.[57]Regelink JC, Minnema MC, Terpos E, et al. Comparison of modern and conventional imaging techniques in establishing multiple myeloma-related bone disease: a systematic review. Br J Haematol. 2013 Jul;162(1):50-61.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjh.12346

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23617231?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Cavo M, Terpos E, Nanni C, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: a consensus statement by the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Apr;18(4):e206-17.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28368259?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Zamagni E, Nanni C, Mancuso K, et al. PET/CT improves the definition of complete response and allows to detect otherwise unidentifiable skeletal progression in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015 Oct 1;21(19):4384-90.

https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/21/19/4384/125050/PET-CT-Improves-the-Definition-of-Complete

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26078390?tool=bestpractice.com

[60]Pawlyn C, Fowkes L, Otero S, et al. Whole-body diffusion-weighted MRI: a new gold standard for assessing disease burden in patients with multiple myeloma? Leukemia. 2016 Jun;30(6):1446-8.

https://www.nature.com/articles/leu2015338

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26648535?tool=bestpractice.com

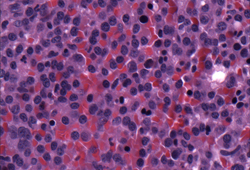

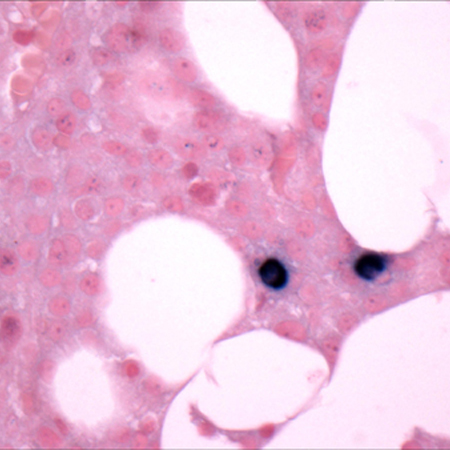

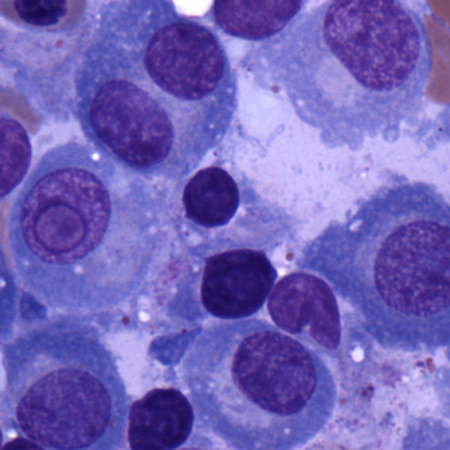

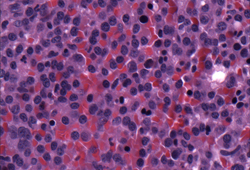

Bone marrow evaluation

Bone marrow biopsy and aspirate are required to verify the presence of monoclonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, and to confirm the diagnosis of MM.[3]Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48.

https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/174646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25439696?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Rajkumar SV. Updated diagnostic criteria and staging system for multiple myeloma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e418-23.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/EDBK_159009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27249749?tool=bestpractice.com

The proportion of clonal bone marrow plasma cells can help to differentiate MM from MGUS. See Classification.

Solitary plasmacytoma, which may progress to MM, is confirmed by the presence of a solitary lesion of bone (or soft tissue) on biopsy, with evidence of clonal plasma cells.[3]Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48.

https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/174646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25439696?tool=bestpractice.com

Bone marrow is normal and there is no evidence of clonal bone marrow plasma cells. Imaging studies are normal (except for the solitary lesion); there is no end-organ damage.[3]Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Nov;15(12):e538-48.

https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/174646

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25439696?tool=bestpractice.com

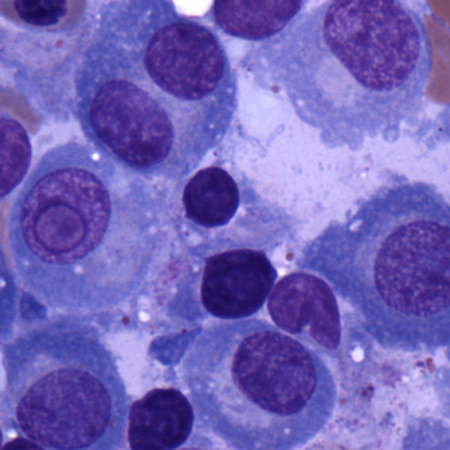

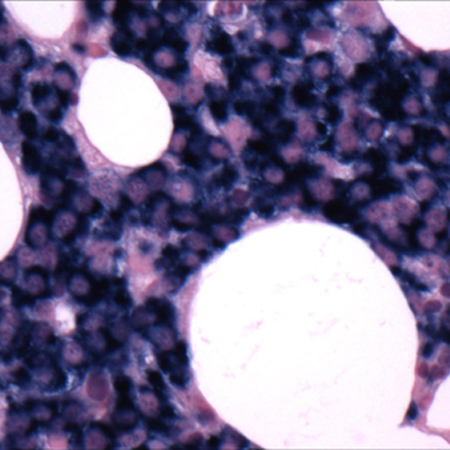

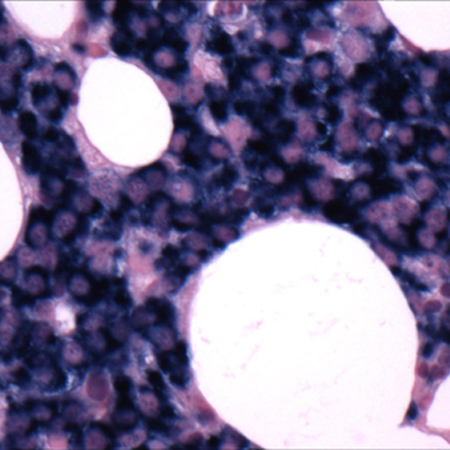

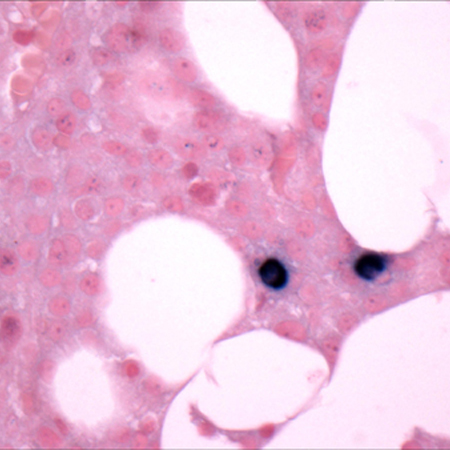

Immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry may be performed on bone marrow samples to confirm the presence of monoclonal plasma cells and to accurately quantify plasma cell involvement.[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bone marrow biopsyCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bone marrow biopsy after histochemical analysis for kappa light chainCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bone marrow biopsy after histochemical analysis for lambda light chainCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Aspirate showing plasma cell infiltrateCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Aspirate showing plasma cell infiltrateCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

Cytogenetic testing

Cytogenetic analysis (e.g., fluorescence in situ hybridisation [FISH]) should be performed on bone marrow samples to identify chromosomal abnormalities considered to increase risk for progression/relapse, for example: del(13q), del(17p), t(4;14), t(11;14), t(14;16), t(14:20), 1q21 gain/amplification, 1p deletion, MYC translocation.[44]Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. Ann Oncol. 2021 Mar;32(3):309-22.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(20)43169-2/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33549387?tool=bestpractice.com

[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Prognostication and risk stratification

Important prognostic markers include serum beta2-microglobulin, serum albumin, cytogenetic abnormalities, creatinine, urea, CRP, serum LDH, and NT-proBNP/BNP.

Serum beta2-microglobulin correlates with clinical stages in the Durie Salmon staging system and is considered the single most important factor for predicting survival.[61]Durie BG, Salmon SE. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma: correlation of measured myeloma cell mass with presenting clinical features, response to treatment, and survival. Cancer. 1975 Sep;36(3):842-54.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1182674?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum albumin levels combined with serum beta2-microglobulin levels have been shown to improve prognostic significance, and this forms the basis of the International Staging System (ISS) classification system used to risk-stratify patients with MM.[62]Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005 May 20;23(15):3412-20.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15809451?tool=bestpractice.com

See Criteria.

Serum LDH and high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, such as del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), and 1q gain/amplification, have been incorporated into revised versions of the ISS classification system (RISS and R2-ISS) to improve risk stratification and prognostication.[63]Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, et al. Revised International Staging System for multiple myeloma: a report from International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Sep 10;33(26):2863-9.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2267

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26240224?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]D'Agostino M, Cairns DA, Lahuerta JJ, et al. Second revision of the International Staging System (R2-ISS) for overall survival in multiple myeloma: a European Myeloma Network (EMN) report within the HARMONY project. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Oct 10;40(29):3406-18.

https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.21.02614?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35605179?tool=bestpractice.com

See Criteria.

Poor prognosis is associated with:[5]Kyle RA. Multiple myeloma: review of 869 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975 Jan;50(1):29-40.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1110582?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Chanan-Khan A, et al. Renal impairment in patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement on behalf of the International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Nov 20;28(33):4976-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20956629?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Pavo N, Cho A, Wurm R, et al. N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is associated with disease severity in multiple myeloma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018 Apr;48(4).

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29417568?tool=bestpractice.com

Increased creatinine and urea, which indicates renal impairment and is reported in up to 50% of patients

Elevated CRP, serum LDH, and NT-proBNP/BNP, indicative of more extensive disease

Additional tests to consider

The following tests may be considered:[45]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and/or next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing on bone marrow specimens; provides further detail about clonal plasma cell genetics that may inform prognostication and aid minimal residual disease (MRD) testing/monitoring during treatment.[67]Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV. The multiple myelomas - current concepts in cytogenetic classification and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul;15(7):409-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29686421?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum viscosity, if hyperviscosity is suspected (particularly those with high levels of M-protein).

Screening for hepatitis B and C, HIV, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus, as clinically indicated.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Aspirate showing plasma cell infiltrateCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Aspirate showing plasma cell infiltrateCourtesy of Dr Robert Hasserjian, Hematopathology, Massachusetts General Hospital; used with permission [Citation ends].