Approach

The initial suspicion of a thymic tumour is usually a radiological one in the appropriate age demographic. There are no specific history or physical examination findings that allow an unequivocal diagnosis of a thymic tumour to be made.[18] If a standard chest radiograph suggests an anterior mediastinal mass, the best initial imaging study is a chest computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast. Nearly all isolated, discrete anterior mediastinal masses in adults over age 40 years, without lymphadenopathy, will prove to represent a thymic tumour. Younger patients who are outside of the typical age group for thymoma should be evaluated for germ cell tumour with biochemical markers (serum alpha-fetoprotein [AFP] and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin [beta-HCG]), and should also be suspected to have lymphoma.

Small, encapsulated lesions are usually resected for both pathological diagnosis and treatment. Tumours that appear locally invasive on imaging should be considered for CT-guided core needle biopsy to confirm the diagnosis due to the potential need for neoadjuvant therapy. However, the need for biopsy should be weighed carefully against the risk of tumour seeding from drop metastases into the pleural space or chest wall from a thymoma.[19][20] If the lesion is suspected to be thymoma and appears likely resectable with primary surgery, pre-operative needle biopsy is not recommended. This decision should be made by an experienced thoracic surgeon or a multidisciplinary team with expertise in treating thymic malignancies. Research shows that positron emission tomography (PET)/CT can be very useful in discriminating between lymphoma and thymoma when a surgeon is presented with a discrete anterior mediastinal mass. A maximum standardised uptake value (SUVmax) of less than 7.5 is virtually pathognomonic of thymoma in this situation, and can guide the decision not to perform pre-operative biopsy.[21]

History

About one third of patients with thymoma are asymptomatic, and diagnosis is often incidental.[7] Once an anterior mediastinal mass is identified and thymoma is suspected, the most important factor to elicit is a history of myasthenia gravis or symptoms consistent with myasthenia gravis (about 40% of patients with thymoma have associated myasthenia gravis).[8][9] Patients with myasthenia gravis may have ocular symptoms (double vision, drooping eyelids), facial and oropharyngeal weakness (difficulty in chewing, dysphagia, or dysarthria), and/or proximal limb weakness (difficulty with getting out of chairs or climbing stairs). Respiratory muscles can also be affected, leading to dyspnoea. Serum studies confirming myasthenia gravis should be performed, and if positive, then the tumour is, with certainty, a thymoma. See Myasthenia gravis (Diagnostic approach).

About one quarter of patients with a thymic tumour have non-specific systemic symptoms such as fever and weight loss, but these types of symptoms are far more common in lymphoma. About one third of patients present with local symptoms such as chest pain, cough, dyspnoea, or, less commonly, symptoms consistent with superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome (e.g., facial and upper-extremity oedema) but these can also occur in lymphoma and germ cell tumour.

Physical examination

The physical examination is generally normal. Muscle weakness may be evident if untreated myasthenia gravis is present. Fatiguable muscle weakness may be localised or generalised, involving the eyelids, extraocular eye muscles, face, oropharynx, neck, respiratory muscles, and/or limbs. Ptosis and diplopia occur early in the majority of patients.[22] Ptosis time (normally >3 minutes) is checked by asking the patient to look up without ptosis developing. When the facial and oropharyngeal muscles are affected there may be a characteristic flattened smile, nasal speech, or difficulty in chewing and swallowing. Examination of the limbs shows proximal muscle weakness with fatigue. Arm abduction time (normally >3 minutes) is checked by asking the patient to hold the upper arms outstretched. There should be no evidence of muscle wasting, and reflexes are normal. Sensation is intact and there is no autonomic dysfunction. In patients with myasthenic crisis, there is severe respiratory involvement.

If the SVC is obstructed, evidence of SVC syndrome may be present; examination may reveal facial plethora, facial and upper-extremity oedema, and distended veins in the neck and chest wall and, occasionally, the abdominal wall.[23]

Rarely, patients are febrile or show signs of weight loss. Left-arm swelling, due to invasion and obstruction of the left innominate vein, is an uncommon finding. Decreased breath sounds may be present on one side due to phrenic nerve invasion and diaphragm paralysis or due to pleural effusion.

Imaging

A chest radiograph is usually the first test performed. A normal chest radiograph does not rule out a small tumour. The most important investigation is a chest CT scan.[24] Intravenous contrast is administered, if there are no contraindications, to evaluate for invasion of blood vessels, which is crucial for preoperative staging and therapeutic planning. It will show the mass, its edge and internal characteristics, which structures it abuts or invades, any associated lymphadenopathy (which increases the chance that the lesion is a lymphoma), and any associated chest pathology such as pleural implants, lung metastases, or evidence of SVC obstruction.

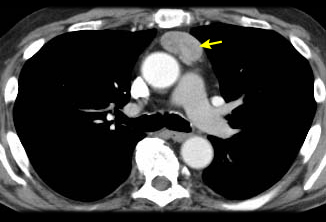

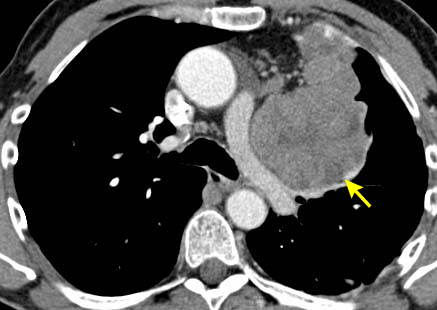

Where iodinated intravenous contrast is contraindicated, chest magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used for staging. This is usually less useful than a CT scan because the tumour details are not as clearly defined. However, chemical-shift MRI may be helpful in differentiating thymic hyperplasia from a thymic tumour.[25] In addition, cardiac-gated MRI may be useful if cardiac invasion is suspected. MRI can also be useful in differentiating between a solid tumour and a benign thymic cyst.[26] Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET-CT scans can be used to help differentiate between thymoma (less FDG avid) versus lymphoma (more FDG avid) for discrete, non-invasive tumours.[21] However, if a tumour appears aggressive on imaging, the PET result does not eliminate the need for core needle biopsy to differentiate thymic malignancy from lymphoma, and to establish a diagnosis for neoadjuvant or definitive non-surgical therapy.[27][28] PET/CT scanning can also be helpful in demonstrating unsuspected nodal or metastatic disease; this is useful when imaging or histological results suggest an aggressive tumour.[29] In general, as the WHO histology worsens, the intensity of the PET uptake (standardised uptake value) increases.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing a typical Masaoka-Koga stage I thymomaFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing Masaoka-Koga stage III thymoma with abutment of the anterior chest wall and invasion of the medial aspect of the left lungFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

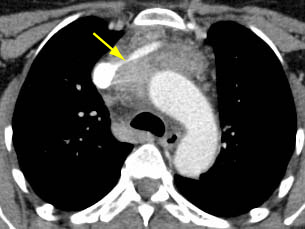

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing Masaoka-Koga stage III thymoma with abutment of the anterior chest wall and invasion of the medial aspect of the left lungFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing thymoma with encasement and invasion of the left innominate veinFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

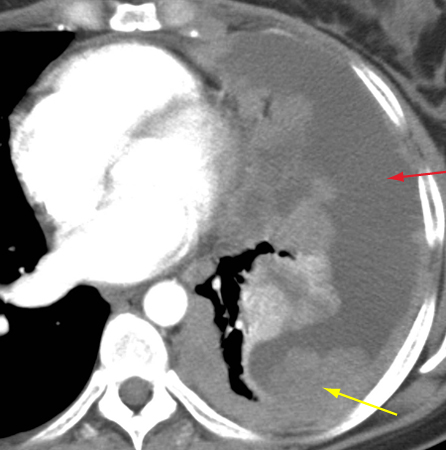

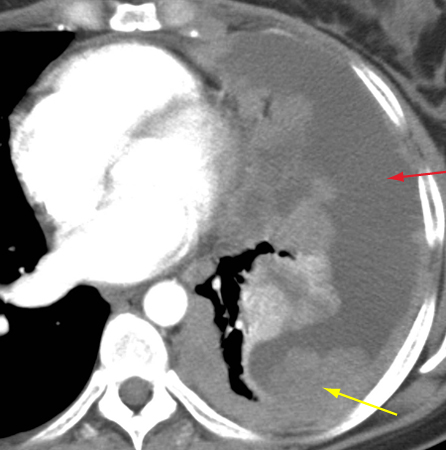

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing thymoma with encasement and invasion of the left innominate veinFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymoma with pleural effusion (red arrow) and extensive pleural metastases (yellow arrow) along posterior chest wallFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymoma with pleural effusion (red arrow) and extensive pleural metastases (yellow arrow) along posterior chest wallFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing thymoma with encasement and invasion of the superior vena cavaFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing thymoma with encasement and invasion of the superior vena cavaFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Other investigations

It is important to obtain a tissue diagnosis when the radiological findings are atypical or show: a locally advanced lesion that may represent either a lymphoma or a more aggressive thymic malignancy (which may require neoadjuvant therapy prior to resection); a metastatic lesion; or an otherwise inoperable tumour. Smaller, non-invasive lesions are usually resected for both pathological diagnosis and treatment unless SUVmax is surprisingly high on PET/CT (over 7.5).

CT-guided core needle biopsy is typically the best way to obtain a pre-treatment tissue diagnosis when required. Fine-needle aspiration is often non-diagnostic, as tissue architecture is usually required to make a diagnosis. An anterior mediastinotomy (Chamberlain's procedure) may be used for large anterior tumours if a core needle biopsy is non-diagnostic. Mediastinoscopy is rarely appropriate, as this approach typically allows access only to the middle mediastinum, not the anterior mediastinum. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) can be used if pleural implants are seen, as optimal pleural biopsy specimens can be obtained using this technique. However, VATS is not appropriate to biopsy the primary tumour, because biopsy carried out through the pleural space risks spilling tumour cells into the pleural space, possibly leading to metastatic pleural implants.

Full blood count, although non-specific, may show anaemia due to paraneoplastic pure-red-cell aplasia. Elevated acetylcholine receptor antibody titre (range varies with assay used) is present in 80% to 90% of patients with myasthenia gravis and may aid diagnosis.[30] Roughly 5% to 10% of patients with thymoma in the absence of myasthenia gravis may have elevation of serum striated muscle antibody.[31] This can be helpful in otherwise difficult diagnostic situations.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT scan of the chest showing Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymoma with pleural effusion (red arrow) and extensive pleural metastases (yellow arrow) along posterior chest wallFrom the collection of Cameron Wright, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer