Aetiology

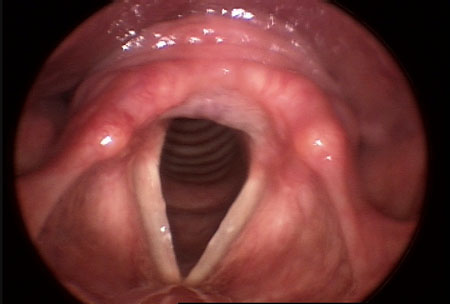

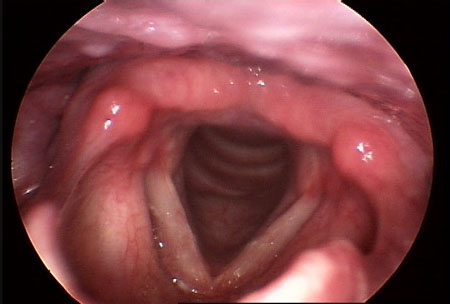

It has been hypothesised that paradoxical vocal fold motion (intermittent laryngeal obstruction) (PVFM/ILO) is a hyper-functional laryngeal syndrome, thought to be secondary to irritable larynx syndrome or hyper-kinetic laryngeal dysfunction, that allows sensorimotor pathways of the central nervous system to remain in a 'spasm-ready' state in response to a variety of sensory triggers.[35][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal larynx: normal colour of vocal folds and surrounding structures, smooth vocal fold edgesFrom the collection of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Irritable larynx: bilateral erythema of the arytenoid complex bilaterally with tissue changes suggestive of early granulomaFrom the collection of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Irritable larynx: bilateral erythema of the arytenoid complex bilaterally with tissue changes suggestive of early granulomaFrom the collection of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health [Citation ends].

The following factors have been associated with the development of PVFM/ILO:[36][37]

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GORD)

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR)

Asthma

Allergies (e.g., dust mites)

Laryngeal muscle tension

Exercise

Airborne irritants

Upper respiratory infection

Postoperative period

Physical and emotional stress

Moderate and severe scores on the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) have been correlated with a diagnosis of PVFM/ILO.[38] Cases of PVFM/ILO associated with exercise are increasingly described as exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction.[37]

Several documented cases of PVFM/ILO following irritant exposure support a possible causal relationship.[39][40][41][42][43]

Psychological issues have been suggested as a possible aetiology for PVFM/ILO, but, although anxiety symptoms have been identified in adolescents and athletes with co-existing PVFM/ILO and asthma, and depression has been associated with the condition, this potential causal link is not supported in the literature.[26][28][31][44] It may therefore be more accurate to associate psychological symptoms with PVFM/ILO than to categorise psychological factors as an actual aetiology for the condition.

Pathophysiology

The larynx is the guardian of the airway. It is a musculocartilaginous structure made up of 2 muscle groups, intrinsic and extrinsic, which receive a rich innervation from a number of cranial nerves. Innervation to the intrinsic muscles is provided by the vagus (X) nerve, which carries bilateral motor and sensory supply via the left and right recurrent and superior laryngeal nerves. The extrinsic muscles are innervated by the trigeminal (V), facial (VII) and hypoglossal (XII) nerves along with the C2 and C3 branches of the ansa cervicalis.[45] All the intrinsic muscles, with the exception of the posterior cricoarytenoid (which is the primary abductor of the larynx), are involved in laryngeal adduction.

The protective function of the airway is both reflexive and voluntary.[46]

The laryngeal adductor response (LAR) is a protective reflex that has been described as a life-sustaining laryngeal reflex.[47] The LAR produces rapid, short-lived vocal fold closure in response to afferent stimuli; when this response is prolonged, it results in laryngospasm.[48] The LAR pathway in the brainstem shares a common sensory region to that which regulates coughing and swallowing.[48]

Important respiratory reflexes are mediated via receptors in the laryngeal mucosa. Mechanoreceptors respond to negative pressure, laryngeal movement, and flow, while chemoreceptors control lower airway protective reflexes including those of coughing and swallowing.[49]

Decreased laryngeal sensitivity has been identified in patients with GORD and cough, and in patients with PVFM/ILO and laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms with a high Reflux Symptom Index. This finding supports the categorisation of I-ILO as a sensorimotor disorder and highlights the role of laryngeal sensitivity in maintaining airway protection.[38][50] Exercise-induced ILO peaks at higher ventilations during intense exercise and then rapidly ceases after stoppage of exercise.[51][52][53][54] This suggests a physical mechanism related to negative-pressure effects during maximum ventilatory effort in anatomically-prone individuals.[55]

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer