Bladder cancer most commonly presents hematuria (visible or nonvisible).[47]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. 2023 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

Cancer-related hematuria is characteristically intermittent. Urologic evaluation is required in all adults with visible (gross or macroscopic) hematuria and should be considered in adults nonvisible (microscopically confirmed) hematuria in the absence of some demonstrable benign cause.[48]Peterson LM, Reed HS. Hematuria. Prim Care. 2019 Jun;46(2):265-73.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0095454319300119?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31030828?tool=bestpractice.com

Awaiting confirmation of nonvisible hematuria on repeated samples (if potential precipitating causes have been excluded) before more extensive evaluation risks missing clinically significant cancers.[49]Jubber I, Shariat SF, Conroy S, et al. Non-visible haematuria for the detection of bladder, upper tract, and kidney cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2020 May;77(5):583-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791622?tool=bestpractice.com

All patients suspected of having bladder cancer require a thorough history and physical exam, although the exam is often unremarkable, particularly in patients with early disease.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

Evaluation of nonvisible hematuria

Nonvisible hematuria, defined as ≥3 red blood cells (RBCs) per high-power field, is a common presentation of bladder cancer.[49]Jubber I, Shariat SF, Conroy S, et al. Non-visible haematuria for the detection of bladder, upper tract, and kidney cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2020 May;77(5):583-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31791622?tool=bestpractice.com

Screening for nonvisible hematuria in populations at risk, combined with appropriate evaluation, improves survival.[18]Cumberbatch MGK, Noon AP. Epidemiology, aetiology and screening of bladder cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2019 Feb;8(1):5-11.

https://tau.amegroups.com/article/view/21474/22804

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30976562?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Messing EM, Madeb R, Young T, et al. Long-term outcome of hematuria home screening for bladder cancer in men. Cancer. 2006 Nov 1;107(9):2173-9.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cncr.22224

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17029275?tool=bestpractice.com

In general, the threshold for cytology and cystoscopy should be low in the absence of a clear cause and complete resolution of hematuria.

The American Urological Association recommends evaluation according to risk of urological cancer.[51]Barocas DA, Boorjian SA, Alvarez RD, et al. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2020 Oct;204(4):778-86.

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/microhematuria

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32698717?tool=bestpractice.com

Low-risk patients meet all of the following criteria:

Women ages <50 years, men ages <40 years

Never smoker or <10 pack years

3-10 RBC per high-power field on a single urine microscopy

No risk factors for urothelial cancer (risk factors include persistent microhematuria, gross hematuria).

Intermediate-risk patients meet one of the following criteria:

Women ages 50-59 years, men ages 40-59 years

10-30 pack year smoking history

11-25 RBC per high-power field on a single urine microscopy

Low-risk patient with no prior evaluation and 3-10 RBC per high-power field on repeat urine microscopy

Additional risk factor for urothelial cancer (additional risk factors include irritative lower urinary tract symptoms, prior pelvic radiation therapy, prior cyclophosphamide/ifosfamide chemotherapy, family history of urothelial cancer, family history of Lynch syndrome, occupational exposure to aromatic amines or benzene chemicals, chronic indwelling foreign body in the urinary tract).

High-risk patients are defined as:

Women and men ages ≥60 years

>30 pack year smoking history

>25 RBC per high-power field on a single urine microscopy

History of gross hematuria

For low-risk patients, urine microscopy may be repeated in 6 months or the urinary tract may be investigated with renal ultrasound and cystoscopy. If microhematuria persists on repeat testing, the patient is reclassified as intermediate or high risk. Intermediate-risk patients should be offered renal ultrasound and cystoscopy. High-risk patients should be offered axial renal imaging, ideally with computed tomography (CT) urography, and cystoscopy.[51]Barocas DA, Boorjian SA, Alvarez RD, et al. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2020 Oct;204(4):778-86.

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/microhematuria

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32698717?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound has the advantage of avoiding radiation exposure, but provides less detail than CT urogram.

Repeat urinalysis within 12 months should be considered for patients whose workup produces a negative result. A positive repeat urinalysis should prompt shared-decision-making regarding repeat evaluation or observation.[51]Barocas DA, Boorjian SA, Alvarez RD, et al. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2020 Oct;204(4):778-86.

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/microhematuria

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32698717?tool=bestpractice.com

See Evaluation of non-visible hematuria.

Evaluation of visible hematuria

All patients with visible blood in the urine require investigation, even when related to overanticoagulation. Complete spontaneous cessation of bleeding does not exclude the possibility of life-threatening malignancy.

Symptoms guide the workup: renal colic should prompt imaging studies with CT or plain x-rays for stone disease; acute onset of frequency and dysuria should prompt urine culture (with antibiotic treatment if indicated). Failure to confirm either of these diagnoses should result in evaluation for bladder cancer with urinalysis, urine cytology, and cystoscopy. CT or magnetic resonance (MR) urography is used to evaluate upper tracts and, like bladder ultrasonography, these tests can demonstrate the presence of bladder cancer in many instances.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[52]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: hematuria. 2019 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69490/Narrative

However, the sensitivity of these tests is insufficient to exclude the diagnosis, particularly of carcinoma in situ, so cystoscopy is still required.[47]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. 2023 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

See Evaluation of visible hematuria.

Evaluation of irritative voiding symptoms

Urinary frequency as the sole symptom of bladder cancer is rare, but does occur. Benign prostatic hypertrophy and overactive bladder are more common causes, but if these are not identified and/or do not respond to treatment, urinary cytology and cystoscopy are indicated.

Burning with urination can occur with carcinoma in situ and high-grade bladder cancer.[53]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

However, risk of bladder or urinary tract cancer in a patient (≥60 years) presenting with dysuria (in the absence of visible hematuria) is low.[54]Schmidt-Hansen M, Berendse S, Hamilton W. The association between symptoms and bladder or renal tract cancer in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2015 Nov;65(640):e769-75.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4617272

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26500325?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Shephard EA, Stapley S, Neal RD, et al. Clinical features of bladder cancer in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 Sep;62(602):e598-604.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3426598

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22947580?tool=bestpractice.com

Common causes of dysuria (e.g., urinary tract infection, prostatitis) should be excluded. See Evaluation of dysuria.

UK guidelines recommend an urgent specialist referral for patients ages ≥60 years who have unexplained nonvisible hematuria and dysuria.[56]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. October 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

Cystoscopy and upper tract imaging

Cystoscopy is key to making the diagnosis.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[47]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. 2023 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

[53]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

Low-grade tumors are papillary and easy to visualize, but high-grade tumors can be papillary, flat, or in situ and difficult to visualize with white light. Visualization at cystoscopy may be improved by narrow-band imaging or blue light (fluorescence) cystoscopy in addition to white light; both appear to improve diagnostic accuracy compared with white light alone.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[57]Zheng C, Lv Y, Zhong Q, et al. Narrow band imaging diagnosis of bladder cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2012 Dec;110(11 Pt B):E680-7.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11500.x/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22985502?tool=bestpractice.com

[58]Burger M, Grossman HB, Droller M, et al. Photodynamic diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer with hexaminolevulinate cystoscopy: a meta-analysis of detection and recurrence based on raw data. Eur Urol. 2013 Nov;64(5):846-54.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0302283813003539?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23602406?tool=bestpractice.com

If a patient undergoes cystoscopy and a lesion suspicious of a urothelial bladder tumor is identified, the patient should be scheduled for TURBT, which will allow the diagnosis to be confirmed pathologically and the extent of the disease to be assessed.

Features suggestive of noninvasive (Ta) disease include papillary tumors having a narrow stalk. Invasive tumors more commonly have a thick stalk or solid configuration. Rough erythematous patches can be indicative of Tis (carcinoma in situ), although urothelium often appears normal. Random biopsies or biopsy of areas positive on blue light or narrow band cystoscopy are needed to properly diagnose Tis.[59]Bhindi B, Kool R, Kulkarni GS, et al. Canadian Urological Association guideline on the management of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer - Full-text. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021 Aug;15(8):E424-60.

https://cuaj.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/7367

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33938798?tool=bestpractice.com

Features suggestive of muscle-invasive (T2) disease include multifocal tumors that are sessile. Vascularity around the tumor is increased. Tumors are often large (>3 cm in diameter), solid, or sessile. Bimanual exam may reveal the mass to extend beyond the bladder (T3-4).

All patients with suspicious lesions detected at cystoscopy should undergo imaging of the upper tract collecting system if they have not already done so. This serves to identify nodal metastasis and obstruction (hydronephrosis).[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

CT urography, which images the urinary tract with contrast during the excretory phase, is the preferred modality.

MR urography is an alternative if CT with contrast is contraindicated. Renal ultrasound with retrograde pyelogram is an alternative third-line option for patients if CT and MRI are contraindicated or unavailable.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[51]Barocas DA, Boorjian SA, Alvarez RD, et al. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2020 Oct;204(4):778-86.

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/microhematuria

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32698717?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging may be obtained before or after TURBT, but the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline recommends CT or MRI before resection if possible.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

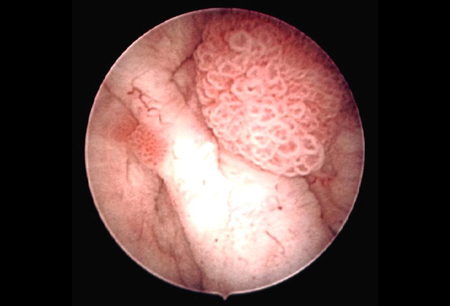

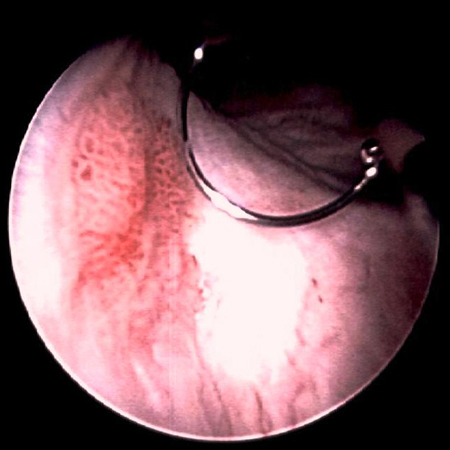

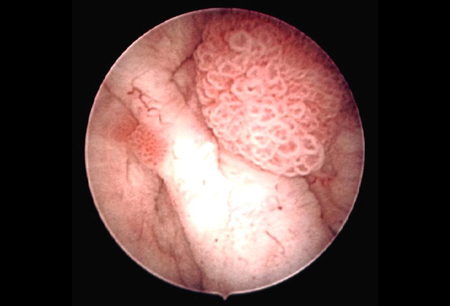

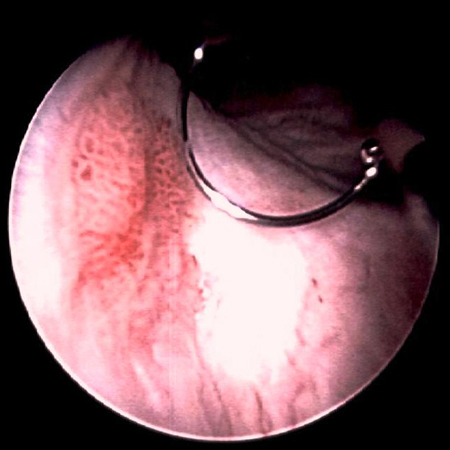

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade, noninvasive (Ta) papillary urothelial carcinoma. Note adjacent satellite tumor, illustrating the field effectFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumorsFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

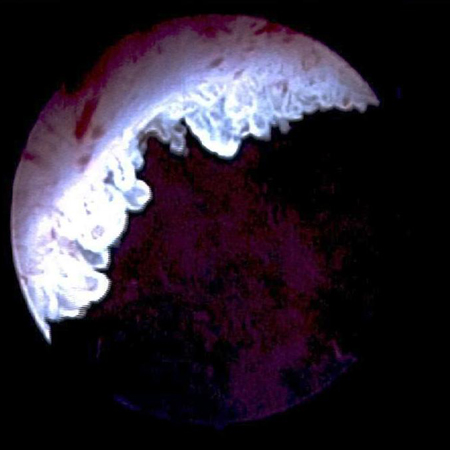

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumorsFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumors surrounded by small satellite tumors with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumor on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumors. Low- and high-grade tumors often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

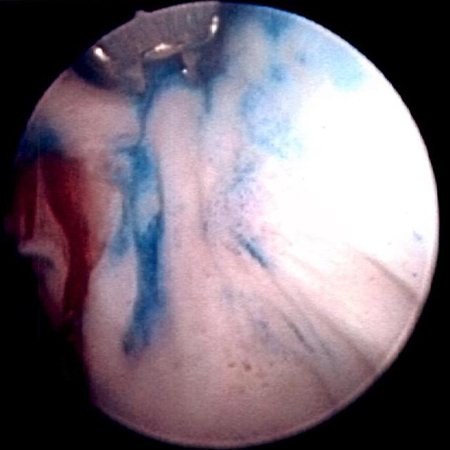

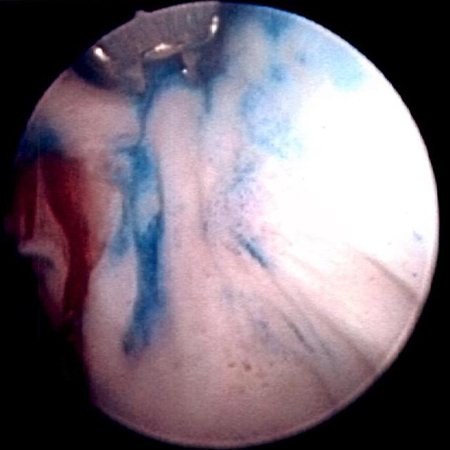

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumors surrounded by small satellite tumors with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumor on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumors. Low- and high-grade tumors often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumor at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of the now Food and Drug Administration-approved hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumors not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

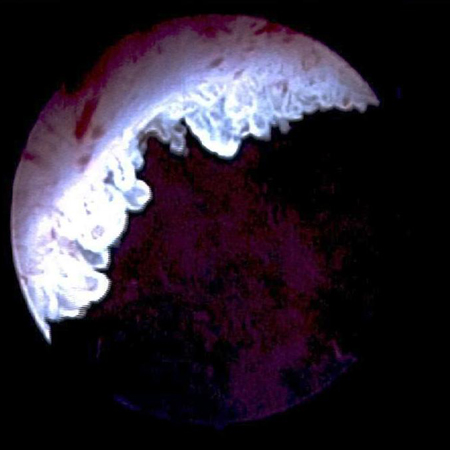

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumor at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of the now Food and Drug Administration-approved hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumors not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

Transurethral resection of a bladder tumor (TURBT)

TURBT is both therapeutic and diagnostic. Initial resection allows pathologic confirmation of the diagnosis with assessment of histology, grade, and depth of invasion. Fragments must be of adequate size and depth to allow for a proper assessment of detrusor muscle invasion. Bimanual exam under anesthesia is performed at the time of TURBT to assess for a palpable mass or fixation to the pelvic wall.[53]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

Enhanced cystoscopy (narrow-band imaging or fluorescence) may improve detection of difficult-to-visualize lesions when used to guide TURBT.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[60]Maisch P, Koziarz A, Vajgrt J, et al. Blue versus white light for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 1;12(12):CD013776.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013776.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34850382?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Ontario Health (Quality). Enhanced visualization methods for first transurethral resection of bladder tumour in suspected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2021;21(12):1-123.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382283

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34484486?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Lai LY, Tafuri SM, Ginier EC, et al. Narrow band imaging versus white light cystoscopy alone for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 8;4(4):CD014887.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD014887.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35393644?tool=bestpractice.com

Blue light (fluorescence) cystoscopy is preferred to guide TURBT because it reduces the risk of recurrence.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[60]Maisch P, Koziarz A, Vajgrt J, et al. Blue versus white light for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 1;12(12):CD013776.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013776.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34850382?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Ontario Health (Quality). Enhanced visualization methods for first transurethral resection of bladder tumour in suspected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2021;21(12):1-123.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382283

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34484486?tool=bestpractice.com

The evidence for reduced recurrence is less certain for narrow-band imaging cystoscopy.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[61]Ontario Health (Quality). Enhanced visualization methods for first transurethral resection of bladder tumour in suspected non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a health technology assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2021;21(12):1-123.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382283

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34484486?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Lai LY, Tafuri SM, Ginier EC, et al. Narrow band imaging versus white light cystoscopy alone for transurethral resection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Apr 8;4(4):CD014887.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD014887.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35393644?tool=bestpractice.com

[63]Gravestock P, Coulthard N, Veeratterapillay R, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of narrow band imaging for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2021 Dec;28(12):1212-7.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/iju.14671

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34453459?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Sari Motlagh R, Mori K, Laukhtina E, et al. Impact of enhanced optical techniques at time of transurethral resection of bladder tumour, with or without single immediate intravesical chemotherapy, on recurrence rate of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. BJU Int. 2021 Sep;128(3):280-9.

https://bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bju.15383

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33683778?tool=bestpractice.com

Multiple bladder biopsies can be done at the time of initial resection to detect carcinoma in situ, which may alter the treatment and increases the risk of upper tract and urethral carcinoma. Carcinoma of the prostatic urethra, if untreated, can progress to aggressive invasive disease. Early invasion of the prostate may be managed by transurethral resection of the prostate if the resection margins are free of disease, but deep invasion carries a poor prognosis even with radical cystectomy.

Guideline-directed risk stratification based on grade and stage determines further treatment after initial TURBT. Repeat resection or simultaneous resection of the prostate may be recommended for some patients to reduce the risk of recurrence. See Management approach.

Further workup for muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Patients with presumptive (based on TURBT and imaging) or pathologically confirmed muscle-invasive bladder cancer should have a complete blood count, chemistry profile (including alkaline phosphatase), chest x-ray, and abdominal/pelvic CT or MRI.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[65]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment staging of urothelial cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69370/Narrative

MRI is considered the best modality for local staging of bladder cancer due to superior soft tissue contrast resolution compared with CT.[53]European Association of Urology. Muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-and-metastatic-bladder-cancer

[65]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment staging of urothelial cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69370/Narrative

One meta-analysis demonstrated that positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan is useful in patients at high risk of metastatic disease (e.g., those with muscle invasion and lymphovascular invasion).[66]Lu YY, Chen JH, Liang JA, et al. Clinical value of FDG PET or PET/CT in urinary bladder cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2012 Sep;81(9):2411-6.

http://www.ejradiology.com/article/S0720-048X(11)00657-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21899971?tool=bestpractice.com

Another meta-analysis reported that CT, MRI, and PET/CT have similar specificities for detection of nodal metastasis, but MRI and PET/CT have superior sensitivity.[67]Crozier J, Papa N, Perera M, et al. Comparative sensitivity and specificity of imaging modalities in staging bladder cancer prior to radical cystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol. 2019 Apr;37(4):667-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30120501?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with symptoms or clinical suspicion of bone metastasis (e.g., bone pain or elevated alkaline phosphatase) should be evaluated with MRI, fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT, or a bone scan.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[65]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment staging of urothelial cancer. 2024 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69370/Narrative

Urine cytology and markers of bladder cancer

Cytology remains the standard and most accepted urinary marker for bladder cancer, but false-negatives are common.

Cytology is not routinely indicated for initial evaluation of hematuria.[51]Barocas DA, Boorjian SA, Alvarez RD, et al. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2020 Oct;204(4):778-86.

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/microhematuria

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32698717?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Tan WS, Sarpong R, Khetrapal P, et al. Does urinary cytology have a role in haematuria investigations? BJU Int. 2019 Jan;123(1):74-81.

https://bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bju.14459

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30003675?tool=bestpractice.com

However, urine cytology has a high sensitivity for high-grade tumors and may be a useful adjunct for patients with irritative voiding symptoms or other risk factors for carcinoma in situ (e.g., smoking, exposure to chemicals, family history).[47]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. 2023 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

[51]Barocas DA, Boorjian SA, Alvarez RD, et al. Microhematuria: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2020 Oct;204(4):778-86.

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/microhematuria

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32698717?tool=bestpractice.com

Urine cytology can also be used for posttreatment surveillance.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[47]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. 2023 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

The sensitivity of urine cytology for low-grade tumors is limited.[47]European Association of Urology. Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. 2023 [internet publication].

https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer

[69]Maas M, Todenhöfer T, Black PC. Urine biomarkers in bladder cancer - current status and future perspectives. Nat Rev Urol. 2023 Oct;20(10):597-614.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37225864?tool=bestpractice.com

Using the Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology (TPS) improves the screening and surveillance potential of urine cytology.[70]Pastorello RG, Barkan GA, Saieg M. Experience on the use of The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytopathology: review of the published literature. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2021 Jan-Feb;10(1):79-87.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213294520303239?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33160893?tool=bestpractice.com

Urine biomarkers for bladder cancer have increased sensitivity compared with urine cytology, but specificity is lower.[43]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: bladder cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[71]Soorojebally Y, Neuzillet Y, Roumiguié M, et al. Urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis and NMIBC follow-up: a systematic review. World J Urol. 2023 Feb;41(2):345-59.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36592175?tool=bestpractice.com

These biomarkers include bladder tumor antigen (BTA), nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22), ImmunoCyt/uCyt+ (a fluorescence immunocytologic diagnostic test using 3 tumor-related monoclonal antibodies), and UroVysion (a fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH] of centromeres of chromosomes 3, 7, and 17 and to the 9p21 locus of chromosome 9 associated with bladder cancer).

Urine biomarkers for bladder cancer may help to determine the most appropriate frequency for follow-up cystoscopy and aid in the diagnosis of high-risk patients, but do not replace cystoscopy.[71]Soorojebally Y, Neuzillet Y, Roumiguié M, et al. Urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer diagnosis and NMIBC follow-up: a systematic review. World J Urol. 2023 Feb;41(2):345-59.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36592175?tool=bestpractice.com

UroVysion® FISH or ImmunoCyt™ may be useful if cytology results are atypical or equivocal cancer.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

Persistence of positive UroVysion® FISH following intravesical BCG (in nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer) suggests poor response and higher risk of progression.[40]American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO joint guideline. 2024 [internet publication].

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/bladder-cancer-non-muscle-invasive-guideline

[72]Whitson J, Berry A, Carroll P, et al. A multicolour fluorescence in situ hybridization test predicts recurrence in patients with high-risk superficial bladder tumours undergoing intravesical therapy. BJU Int. 2009 Aug;104(3):336-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19220253?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Kamat AM, Dickstein RJ, Messetti F, et al. Use of fluorescence in situ hybridization to predict response to bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy for bladder cancer: results of a prospective trial. J Urol. 2012 Mar;187(3):862-7.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3278506

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22245325?tool=bestpractice.com

In a review of published series, sensitivity (SN) and specificity (SP) were as follows:[74]Budman LI, Kassouf W, Steinberg JR. Biomarkers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008 Jun;2(3):212-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2494897

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18682775?tool=bestpractice.com

Hematuria dipstick: 47% to 93% SN, 51% to 84% SP

Cytology: 12% to 85% SN, 78% to 100% SP

BTA Trak: 51% to 100% SN, 73% to 92% SP

NMP22 BladderChek: 50% to 65% SN, 40% to 90% SP

ImmunoCyt/uCyt+: 81% to 89% SN, 61% to 78% SP

UroVysion FISH: 69% to 100% SN, 65% to 96% SP.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumorsFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade urothelial carcinoma seeding in the prostatic urethra; illustrated is the loop electrode used to resect bladder tumorsFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumors surrounded by small satellite tumors with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumor on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumors. Low- and high-grade tumors often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-grade tumors surrounded by small satellite tumors with small, uniform fronds. In the foreground is a solid tumor on a broad base, a typical appearance of high-grade tumors. Low- and high-grade tumors often occur in the same patientFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumor at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of the now Food and Drug Administration-approved hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumors not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Methylene blue-stained tumor at the right bladder neck. Staining with 0.2% methylene blue (or use of the now Food and Drug Administration-approved hexaminolevulinate blue-light fluorescence cystoscopy) can help identify tumors not seen otherwiseFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Carcinoma in situ of the bladder; this can appear as a rough, erythematous patch in the bladder, but often the urothelium appears normal; random biopsy or biopsy of areas stained by 0.2% methylene blue, illustrated here, is needed to make the diagnosisFrom the collection of Donald Lamm, MD, FACS [Citation ends].