Etiology

Approximately 50% to 70% of BPPV occurs without a known cause and is referred to as primary (or idiopathic) BPPV.[7] The remainder is termed secondary BPPV and is associated with a range of underlying conditions, including head trauma, labyrinthitis, vestibular neuronitis, Meniere disease (endolymphatic hydrops), migraines, ischemic processes, and iatrogenic causes (otologic and nonotologic surgery, repositioning maneuvers).[7]

Pathophysiology

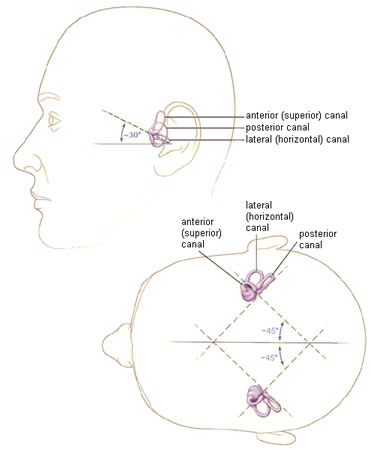

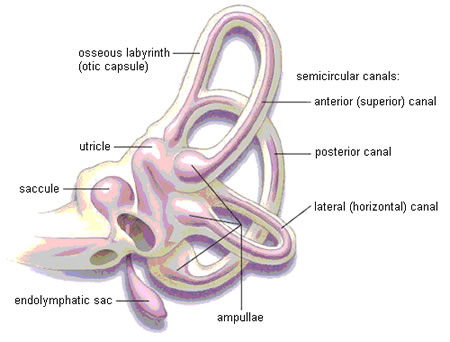

The semicircular canals detect angular acceleration of the head and are involved in enabling visual fixation on a target while the head is moving (the vestibulo-ocular reflex). However, an abnormal signal arising from a canal leads to the misperception of movement (vertigo) and nystagmus of the eye in the plane of that canal. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Spatial orientation of the semicircular canalsParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693. Used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osseous (gray/white) and membranous (lavender) labyrinth of the left inner earParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693. Used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osseous (gray/white) and membranous (lavender) labyrinth of the left inner earParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693. Used with permission [Citation ends].

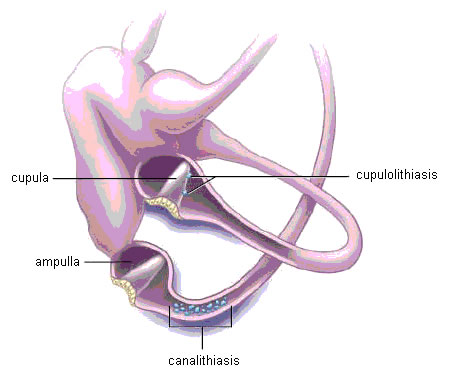

The two prevailing pathophysiologic mechanisms of BPPV are canalithiasis and cupulolithiasis.[8][9][10][11] Canalithiasis is the major mechanism of all subtypes of BPPV. Cupulolithiasis plays a significant role in lateral (horizontal) canal BPPV, although canalithiasis still remains more common even in this type of BPPV.[7][12][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Left inner ear. Depiction of canalithiasis of the posterior canal and cupulolithiasis of the lateral canalParnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003:169:681-693. Used with permission [Citation ends].

Under normal physiologic conditions the cupula has the same density as the surrounding endolymph, and consequently the semicircular canals are normally not sensitive to linear acceleration (i.e., gravity). In canalithiasis, free-floating endolymph particles called canaliths (which are possibly otoconia or calcium carbonate particles), originating from the otolith membrane in the utricle, migrate into the semicircular canals over time via natural head movements.[13] The canalith particles are denser than the surrounding endolymph fluid and therefore respond to gravity. These canaliths tend to settle into the posterior semicircular canal in particular, because in the supine and upright positions it is the most gravity-dependent part of the vestibular labyrinth. In addition, the posterior semicircular canal has an impermeable cupular barrier that traps particles in the long arm of the canal.[7]

The orientation of the anterior (superior) and lateral (horizontal) semicircular canals are such that the cupulae tend not to trap particles in the canal, so that if any particles do enter the nonampullated canal end, natural head movements alone allow them to fall back out into the utricle whence they came.[7]

Over time these particles accumulate and reach a critical mass that provides sufficient force to displace the cupula. Consequently, specific head movements in the plane of the affected canal, combined with head movements that align the affected canal more vertically, allow canalith particles to gravitate downward, causing a hydrodynamic drag force that induces an endolymph current and deflects the cupula, thereby stimulating the hair cells.[7]

This pathologically activates the vestibulo-ocular reflex, triggering the slow phase of nystagmus, as the eyes respond to canalith-induced deflection of the cupula. This is then followed by a saccade in the opposite direction (the fast phase of nystagmus) via a corrective response by the brain. At the same time there is a corresponding misperception of movement, which is vertigo. The vertigo resolves when the provocative head movement stops, the canalith particles reach the limit of their descent, and the cupula returns to its normal resting position.[7]

In cupulolithiasis, the dense canalith particles adhere to the cupula, which, as in canalithiasis, causes it to be gravity-sensitive. However, because this is a fixed cupular deposit, particle repositioning maneuvers may not be as effective, and thus cupulolithiasis may represent the more chronic form of BPPV.[7]

An important part of diagnosing and properly treating an episode of BPPV is by observing the specific nystagmus profile. The anatomic orientation of the posterior semicircular canal causes it to respond to both vertical (neck flexion-extension) and lateral head-tilting motions; hence, the nystagmus has both a torsional (rotatory) and vertical up-beating (toward the forehead) component. The anterior (superior) canal is aligned at a right angle to the posterior canal, and the nystagmus response will similarly possess a torsional and vertical component, but the vertical component will be in the opposite down-beating direction (away from the forehead). The lateral semicircular canal is oriented such that the nystagmus will not have a torsional component but instead only a horizontal component.[7][14][15]

A subset of patients will have subjective BPPV, where the symptoms of vertigo are present without signs of nystagmus on physical exam. Possible explanations of the subjective BPPV phenomenon include subtle nystagmus difficult to detect by the clinician, a fatigued response, or a less noxious or severe type of BPPV that is able to elicit the sensation of vertigo but not strong enough to stimulate the vestibulo-ocular pathway.[16]

Classification

Clinical classification

Classification in the literature is based on the affected canal, pathophysiologic mechanism, etiology, course of the disease, and physical examination response.[1]

Site

Posterior canal: more common

Lateral (horizontal) canal: less common

Anterior (superior) canal: rare.

Pathophysiology

Canalithiasis

Cupulolithiasis.

Etiology

Primary (idiopathic)

Secondary.

Course

Self-limited

Recurrent

Chronic.

Physical exam

Objective: symptoms of vertigo are present with signs of nystagmus

Subjective: symptoms of vertigo are present without signs of nystagmus.

Other

Unilateral: one side involved; majority of cases

Bilateral: both sides involved simultaneously; usually the result of a closed-head injury.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer