Management of DVT is based on an algorithmic diagnostic approach. History and physical exam are relatively insensitive and nonspecific, so must be combined with other diagnostic tests in the clinical decision-making process.

Diagnostic algorithm for DVT

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Algorithm for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosisCreated by the BMJ Knowledge Centre [Citation ends].

History

Key information includes the presence or absence of a prior history of DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) as well as recent exposure to any of the common provoking risk factors (see the Risk factors section).

The patient may report symptoms of calf swelling (or, more rarely, swelling of the entire leg), localized pain along the deep venous system, edema, or dilated superficial veins over the foot and leg. Symptoms range from severe to very subtle, and patients can be asymptomatic.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

Signs and physical exam

Signs of DVT include swelling and visible skin changes. Unilateral leg swelling can be assessed by measuring the circumference of the leg 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity. Any difference between the symptomatic and asymptomatic leg increases the probability of DVT, and a difference of >3 cm between the extremities further increases the probability.

There may be edema and dilated collateral superficial veins on the affected side. Tenderness along the path of the deep veins (posterior calf compression, compression of the popliteal fossa, and compression along the inner anterior thigh from the groin to the adductor canal) might be present.

Two physical exam maneuvers that have been taught historically - tenderness with dorsiflexion of the foot (Homans sign) or calf pain on palpation (Pratt sign) - may be present; however, they have poor sensitivity and specificity, and are not a component of current risk assessment models.[112]Galanis T, Eraso L, Perez A, et al. Venous thromboembolic disease. In: Slovut DP, Dean SM, Jaff MR, et al, eds. Comprehensive review in vascular and endovascular medicine. Vol I. Minneapolis, MN: Cardiotext Publishing; 2012:251-84.

With a high burden of thrombosis, especially in the iliac and femoral veins, the swelling can obstruct deep and superficial venous outflow as well as arterial inflow, leading to phlegmasia cerulea dolens (PCD). PCD is characterized by marked swelling, significant pain, and cyanosis.[113]Cooper RM, Hayat SA. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, a rare complication of deep vein thrombosis. Emerg Med J. 2008 Jun;25(6):334.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18499813?tool=bestpractice.com

PCD is a rare, life-threatening complication that may lead to arterial ischemia and can ultimately cause gangrene, with high amputation and mortality rates.[113]Cooper RM, Hayat SA. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, a rare complication of deep vein thrombosis. Emerg Med J. 2008 Jun;25(6):334.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18499813?tool=bestpractice.com

[114]Chaochankit W, Akaraborworn O. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens with compartment syndrome. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018 Sep 25;11(3):355-7.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/avd/11/3/11_cr.18-00030/_pdf/-char/en

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30402189?tool=bestpractice.com

If PCD is suspected, immediate treatment should be started and the patient should be evaluated for interventional therapy such as catheter-directed thrombolysis or aspiration (usually performed by interventional radiology or vascular surgery) or, more rarely, open thrombectomy (performed by a vascular surgeon).[40]Kakkos SK, Gohel M, Baekgaard N, et al. Editor's choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2021 clinical practice guidelines on the management of venous thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021 Jan;61(1):9-82.

https://www.ejves.com/article/S1078-5884(20)30868-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33334670?tool=bestpractice.com

[114]Chaochankit W, Akaraborworn O. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens with compartment syndrome. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018 Sep 25;11(3):355-7.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/avd/11/3/11_cr.18-00030/_pdf/-char/en

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30402189?tool=bestpractice.com

This is a life- and limb-threatening emergency and the results of investigations should not delay starting treatment.[40]Kakkos SK, Gohel M, Baekgaard N, et al. Editor's choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2021 clinical practice guidelines on the management of venous thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021 Jan;61(1):9-82.

https://www.ejves.com/article/S1078-5884(20)30868-6/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33334670?tool=bestpractice.com

[114]Chaochankit W, Akaraborworn O. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens with compartment syndrome. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018 Sep 25;11(3):355-7.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/avd/11/3/11_cr.18-00030/_pdf/-char/en

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30402189?tool=bestpractice.com

The signs of DVT are not specific and may also occur in other conditions, such as large or ruptured popliteal cyst (Baker cyst), cellulitis, and musculoskeletal trauma or injury (calf bleeding or hematoma, ruptured Achilles tendon, or ruptured plantaris tendon).[115]Tovey C, Wyatt S. Diagnosis, investigation, and management of deep vein thrombosis. BMJ. 2003 May 31;326(7400):1180-4.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1126050

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12775619?tool=bestpractice.com

In many patients, the diagnosis of cellulitis or a musculoskeletal injury is straightforward, but DVT may coexist with these conditions.

Patients with suspected DVT

When a patient is suspected of DVT, the pretest probability of DVT should be determined using a validated prediction rule and/or clinical judgment (see below).[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

A prediction rule may be preferable, particularly for clinicians who rarely evaluate patients for PE, because clinical judgment lacks standardization.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

If there is a high probability for DVT, but diagnostic testing cannot be performed promptly, then empiric anticoagulation at an initiation dose should be provided, if not contraindicated, while awaiting results of diagnostic testing.[18]Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021 Dec;160(6):e545-608.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(21)01506-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34352278?tool=bestpractice.com

Assessing clinical probability

Clinical probability, assessed by a validated prediction rule and/or clinical judgment, is the basis for all diagnostic strategies for DVT.[41]Mazzolai L, Ageno W, Alatri A, et al. Second consensus document on diagnosis and management of acute deep vein thrombosis: updated document elaborated by the ESC Working Group on aorta and peripheral vascular diseases and the ESC Working Group on pulmonary circulation and right ventricular function. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022 May 27;29(8):1248-63.

https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/29/8/1248/6319853

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34254133?tool=bestpractice.com

Suspected DVT can often be excluded without an imaging test, avoiding the expense (and the risks of radiation and contrast of venography). Therefore, the first step in making the diagnosis of DVT is to establish the probability that a DVT is present using a risk assessment model such as one based on the Wells score in combination with a D-dimer level. Using this approach, more than one third of patients suspected of DVT can have the diagnosis safely excluded without imaging.[116]Douma RA, Mos IC, Erkens PM, et al. Performance of 4 clinical decision rules in the diagnostic management of acute pulmonary embolism: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Jun 7;154(11):709-18.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21646554?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with a non-high (low or intermediate) clinical probability of DVT, D-dimer measurement is recommended to assess the need for imaging.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

Those with a high clinical probability of DVT, or with an abnormal D-dimer, should proceed immediately to imaging. In patients with a high pretest probability of DVT, anticoagulation should be initiated while awaiting imaging results.[18]Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021 Dec;160(6):e545-608.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(21)01506-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34352278?tool=bestpractice.com

[19]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing. Aug 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158

There are several risk assessment models available to assess the clinical probability of DVT; however, the Wells score provides a method to determine the clinical probability of DVT and is the most widely accepted pretest probability tool used in diagnostic algorithms for DVT.[117]Blann AD, Lip GY. Venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2006 Jan 28;332(7535):215-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1352055

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16439400?tool=bestpractice.com

[118]Scarvelis D, Wells PS. Diagnosis and treatment of deep-vein thrombosis. CMAJ. 2006 Oct 24;175(9):1087-92.

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/175/9/1087

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17060659?tool=bestpractice.com

Wells score

The Wells score is not a definitive test but should be determined in all patients with suspected DVT. It provides a method to determine the clinical probability of DVT and is the most widely accepted pretest probability tool used in diagnostic algorithms for DVT.[117]Blann AD, Lip GY. Venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2006 Jan 28;332(7535):215-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1352055

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16439400?tool=bestpractice.com

[118]Scarvelis D, Wells PS. Diagnosis and treatment of deep-vein thrombosis. CMAJ. 2006 Oct 24;175(9):1087-92.

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/175/9/1087

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17060659?tool=bestpractice.com

If the Wells score is 2 or greater, the condition is likely (absolute risk is approximately 40%).[117]Blann AD, Lip GY. Venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2006 Jan 28;332(7535):215-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1352055

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16439400?tool=bestpractice.com

[118]Scarvelis D, Wells PS. Diagnosis and treatment of deep-vein thrombosis. CMAJ. 2006 Oct 24;175(9):1087-92.

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/175/9/1087

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17060659?tool=bestpractice.com

People with a score of <2 are unlikely to have a DVT (probability <15%).[117]Blann AD, Lip GY. Venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2006 Jan 28;332(7535):215-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1352055

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16439400?tool=bestpractice.com

[118]Scarvelis D, Wells PS. Diagnosis and treatment of deep-vein thrombosis. CMAJ. 2006 Oct 24;175(9):1087-92.

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/175/9/1087

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17060659?tool=bestpractice.com

The criteria are as follows:

Active cancer (any treatment within past 6 months): 1 point

Calf swelling where affected calf circumference measures >3 cm more than the other calf (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity): 1 point

Prominent superficial veins (nonvaricose): 1 point

Pitting edema (confined to symptomatic leg): 1 point

Swelling of entire leg: 1 point

Localized pain along distribution of deep venous system: 1 point

Paralysis, paresis, or recent cast immobilization of lower extremities: 1 point

Recent bed rest for >3 days or major surgery requiring regional or general anesthetic within past 12 weeks: 1 point

Previous history of DVT or pulmonary embolism: 1 point

Alternative diagnosis at least as probable: subtract 2 points.

This test has not been validated in the pregnant population and, therefore, should not be routinely used to risk stratify a pregnant woman with a suspected DVT. A clinical prediction rule termed the LEFt score has been developed specifically for the pregnant population; however, this rule has yet to be rigorously validated and should also not be used routinely.[119]Chan WS, Lee A, Spencer FA, et al. Predicting deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy: out in "LEFt" field? Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jul 21;151(2):85-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19620161?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Wells ScoreMazzolai L, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute deep vein thrombosis. Eur Heart J. 2018 Dec 14;39(47):4208-18 [Citation ends].

Confirmation of DVT

Confirmation of the diagnosis requires documentation of a blood clot in a deep vein in the leg, pelvis, or vena cava by an imaging study (duplex ultrasound or a vascular contrast study such as a computed tomographic [CT] venography).

DVT likely (high clinical probability)

Imaging, usually compression or duplex ultrasound, should be ordered for patients with a DVT likely (high) clinical (pretest) probability.[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

In these patients D-dimer level should not be performed; a normal plasma D-dimer level does not obviate the need for imaging in this patient population.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

DVT unlikely (intermediate or low clinical probability)

Patients with a DVT unlikely clinical (pretest) probability should have D-dimer levels tested. Patients with abnormal D-dimer (defined by laboratory standard or adjusted threshold - see below) should undergo imaging.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

Quantitative D-dimer level

D-dimer is a breakdown product of cross-linked fibrin; hence, if there is an acute clot, D-dimer level is likely to be elevated. A quantitative or highly sensitive D-dimer test is therefore a useful test to exclude the presence of an acute DVT. There are many tests available for D-dimer, but the best are highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests. Each of the multiple tests that are available on the market has its own normal cutoff value. D-dimer can be reported in different units, so the specific cutoff value for the test being used should be noted.[121]Hasegawa M, Wada H, Yamaguchi T, et al. The evaluation of D-dimer levels for the comparison of fibrinogen and fibrin units using different D-dimer kits to diagnose VTE. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018 May;24(4):655-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28480752?tool=bestpractice.com

D-dimer level is indicated in all patients where DVT is considered unlikely (e.g., Wells score of <2). In these patients a normal D-dimer value excludes the diagnosis of DVT.[122]Ten Cate-Hoek AJ, Prins MH. Management studies using a combination of D-dimer test result and clinical probability to rule out venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2005 Nov;3(11):2465-70.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01556.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16150049?tool=bestpractice.com

This high negative predictive value is useful to reduce the need for further wasteful imaging or immediate anticoagulation with its associated risks. An elevated, abnormal D-dimer test, when combined with a low clinical probability for DVT, should prompt the clinician to proceed with imaging.

Clinicians should not obtain a D-dimer measurement in patients with a high clinical probability of DVT; immediate imaging is indicated.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

In outpatients with a suspected venous thromboembolic event, point-of-care testing of D-dimer can contribute important information and guide patient management in patients with a low-probability score on a clinical decision rule.[123]Geersing GJ, Janssen KJ, Oudega R, et al. Excluding venous thromboembolism using point of care D-dimer tests in outpatients: a diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009 Aug 14;339:b2990.

https://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b2990

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19684102?tool=bestpractice.com

For example, a negative D-dimer excludes DVT when the pretest probability is low.

D-dimer is not a definitive test. Elevated levels are highly sensitive but nonspecific.[117]Blann AD, Lip GY. Venous thromboembolism. BMJ. 2006 Jan 28;332(7535):215-9.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1352055

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16439400?tool=bestpractice.com

[124]Fancher TL, White RH, Kravitz RL. Combined use of rapid D-dimer testing and estimation of clinical probability in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis: systematic review. BMJ. 2004 Oct 9;329(7470):821. [Erratum in: BMJ. 2004 Nov 20;329(7476):1236.]

https://www.bmj.com/content/329/7470/821

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15383452?tool=bestpractice.com

[125]Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Douketis J, et al. Management of suspected deep venous thrombosis in outpatients by using clinical assessment and D-dimer testing. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jul 17;135(2):108-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11453710?tool=bestpractice.com

It is frequently abnormal in patients who are older, are acutely ill, have underlying hepatic disease, have an infection, or are pregnant.

Regardless of the patient group, D-dimer has a low positive predictive value. Approaches to mitigate the low specificity of D-dimer have included adjusting the cutoff value based on the patient's age (e.g., age [years] × 10 micrograms/L [using D-dimer assays with a cutoff of 500 micrograms/L] in patients >50 years old) or by the pretest probability of DVT (if using a risk assessment model with three categories).[126]Takach Lapner S, Julian JA, Linkins LA, et al. Comparison of clinical probability-adjusted D-dimer and age-adjusted D-dimer interpretation to exclude venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2017 Oct 5;117(10):1937-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28771280?tool=bestpractice.com

[127]Lim W, Le Gal G, Bates SM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018 Nov 27;2(22):3226-56; reaffirmed 2022.

https://ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/2/22/3226/16134/American-Society-of-Hematology-2018-guidelines-for

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30482764?tool=bestpractice.com

The D-dimer assay plays a limited role in pregnancy due to its natural rise with each trimester.[128]Francalanci I, Comeglio P, Liotta AA, et al. D-dimer concentrations during normal pregnancy, as measured by ELISA. Thromb Res. 1995 Jun 1;78(5):399-405.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7660356?tool=bestpractice.com

However, a negative D-dimer test may be useful in ruling out a diagnosis of DVT in these patients.[129]Chan WS, Chunilal S, Lee A, et al. A red blood cell agglutination D-dimer test to exclude deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Aug 7;147(3):165-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17679704?tool=bestpractice.com

Initial imaging studies

Venous duplex ultrasound (DUS)

Venous DUS is the first-line test recommended in all patients with a Wells score of 2 or more, or in patients with a Wells score <2 who have an elevated D-dimer level.[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

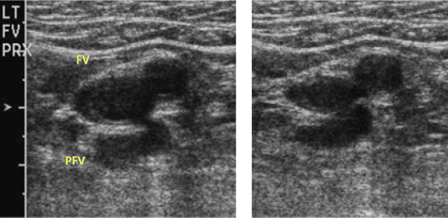

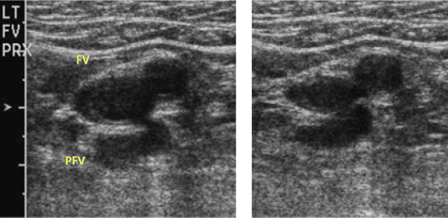

Diagnosis of an acute clot is based on the inability to completely collapse the walls of the vein in the transverse plane by pressing down on the vein with a transducer probe (the presence of thrombus prevents compression).[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Short-axis ultrasound view showing the femoral vein and profunda femoris vein adjacent to the femoral artery before compression (left) and compressed (right)From the collection of Jeffrey W. Olin; used with permission [Citation ends].

Venous DUS has high sensitivity and specificity of over 95%.[130]Segal JB, Eng J, Tamariz LJ, et al. Review of the evidence on diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Ann Fam Med. 2007 Jan-Feb;5(1):63-73.

https://www.annfammed.org/content/5/1/63

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17261866?tool=bestpractice.com

Venous ultrasound has a high sensitivity because: 1) deep veins in the lower extremities are easily visualized; 2) it scans multiple areas, making it likely that at least a portion of a clot is detected; and 3) compression readily identifies intravascular thrombus.

There are two well-validated techniques to perform venous ultrasound of the leg. Whole-leg ultrasound assesses the veins of both the upper leg and calf. It takes longer to perform, is technically more demanding, and identifies calf-vein DVT, which might resolve without treatment (thus can lead to over-diagnosis and potentially over-treatment with anticoagulation, subjecting the patient to possible bleeding complications). However, it is able to reach a diagnostic conclusion in a single session.[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

Proximal DUS assesses only the veins above the calf. While faster and simpler, if negative it must be repeated 5 to 7 days later to exclude any undetected calf-vein DVTs that have propagated proximally.

Ultrasound cannot provide the exact age of a vein clot, but comparison to prior imaging studies, if available, is a reliable method for differentiating acute from preexisting thrombosis.

Ultrasound testing can be limited to only the proximal deep venous system, so long as patients with a positive D-dimer or high probability and who have an initially normal proximal ultrasound undergo a repeat ultrasound in 5-7 days.[131]Bernardi E, Camporese G, Büller HR, et al; Erasmus Study Group. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1653-9.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1107744

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18840838?tool=bestpractice.com

A serial ultrasound strategy may be necessary to exclude proximal extension of the thrombus into the popliteal veins or beyond.[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

In high-probability patients, a repeat ultrasound is indicated in 5-7 days if the initial ultrasound test is normal.

In low-probability patients, a repeat ultrasound is indicated in 5-7 days if D-dimer level is elevated and initial ultrasound is normal.

The subsequent rate of venous thromboembolism (VTE) following a negative diagnostic evaluation does not appear to meaningfully differ between whole-leg ultrasound and serial proximal ultrasound.[131]Bernardi E, Camporese G, Büller HR, et al; Erasmus Study Group. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1653-9.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1107744

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18840838?tool=bestpractice.com

Venous DUS is the initial test of choice for a pregnant woman suspected of having a DVT. The American College of Chest Physicians advocates the use of serial, proximal ultrasonography if a DVT is suspected in pregnant women.[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com

Color flow Doppler

Color flow Doppler and pulse-wave are sometimes done in conjunction with B-mode image ultrasonography. Findings can include reduced or absent spontaneous flow, lack of respiratory variation, intraluminal echoes, or color flow patency abnormalities. A curvilinear probe may be used to attempt to visualize the iliac veins, but this modality does not allow for compression. The absence of respiratory variations on pulse-wave Doppler raises the suspicion of a proximal venous obstruction.[120]American College of Radiology; American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine; Society of Pediatric Radiology; Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. ACR-AIUM-SPR-SRU practice parameter for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examination. 2024 [internet publication].

https://gravitas.acr.org/PPTS/GetDocumentView?docId=58+&releaseId=2

It has low sensitivity (75%) and medium specificity (85%).[132]Remy-Jardin M, Remy J, Deschildre F, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with spiral CT: comparison with pulmonary angiography and scintigraphy. Radiology. 1996 Sep;200(3):699-706.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8756918?tool=bestpractice.com

[133]Lensing AW, Doris CI, McGrath FP, et al. A comparison of compression ultrasound with color Doppler ultrasound for the diagnosis of symptomless postoperative deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 1997 Apr 14;157(7):765-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9125008?tool=bestpractice.com

CT with contrast (CT venography) may be more accurate than ultrasound at detecting thrombosis in larger veins of the abdomen and pelvis, and may be utilized when more proximal thrombosis is clinically suspected or suggested by flow patterns on Doppler ultrasound.[132]Remy-Jardin M, Remy J, Deschildre F, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with spiral CT: comparison with pulmonary angiography and scintigraphy. Radiology. 1996 Sep;200(3):699-706.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8756918?tool=bestpractice.com

Laboratory tests

Other laboratory tests are seldom of any value in the diagnosis of an acute DVT. Occasionally, laboratory tests may point to an underlying cause of a newly diagnosed DVT, such as abnormalities suggesting the presence of a malignancy (e.g., anemia or leukopenia on complete blood count). A high platelet count may suggest essential thrombocytosis or a myeloproliferative disorder. Baseline platelet count, activated partial thromboplastin time, international normalized ratio, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine are important before commencing anticoagulation, depending upon the anticoagulant agent chosen for therapy. Low platelet count may preclude the use of some anticoagulants. Liver function tests may detect abnormalities precluding the use of certain anticoagulants, because some are not approved in varying degrees of hepatic dysfunction.

Thrombophilia screen

Thrombophilia commonly refers to five hereditary conditions (factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene 20210A, deficiencies in antithrombin, protein C deficiency, and protein S deficiency) and antiphospholipid syndrome (an acquired condition). However, many gene variants and acquired conditions modify thrombosis risk.[134]Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016 Jan;41(1):154-64.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26780744?tool=bestpractice.com

Indications for screening are controversial.[134]Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016 Jan;41(1):154-64.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26780744?tool=bestpractice.com

[135]Connors JM. Thrombophilia testing and venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 21;377(12):1177-87.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28930509?tool=bestpractice.com

Hereditary thrombophilia does not sufficiently modify the predicted risk of recurrent thrombosis to affect treatment decisions and does not significantly increase the predicted risk of recurrent VTE after a provoked DVT; a conservative approach to testing is reasonable, and in general guidelines discourage testing in this setting.[18]Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021 Dec;160(6):e545-608.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(21)01506-3/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34352278?tool=bestpractice.com

[55]Society for Vascular Medicine. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2022 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230209062506/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/society-for-vascular-medicine

[56]American Society of Hematology. Ten things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2021.

https://web.archive.org/web/20230316185857/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-society-of-hematology

Some guidelines suggest testing only in situations where the result is likely to change a clinical decision (such as in patients with unprovoked DVT or PE who are considering stopping anticoagulants).[19]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing. Aug 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158

[54]Middeldorp S, Nieuwlaat R, Baumann Kreuziger L, et al. American Society of Hematology 2023 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: thrombophilia testing. Blood Adv. 2023 Nov 28;7(22):7101-38.

https://ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/7/22/7101/495845/American-Society-of-Hematology-2023-guidelines-for

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37195076?tool=bestpractice.com

[136]Klok FA, Ageno W, Ay C, et al. Optimal follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function, in collaboration with the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Atherosclerosis and Vascular Biology, endorsed by the European Respiratory Society. Eur Heart J. 2022 Jan 25;43(3):183-9.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/3/183/6454843

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34875048?tool=bestpractice.com

If a hereditary thrombophilia screen is considered, it should be deferred until a minimum of 3 months of anticoagulant therapy has been completed because some thrombophilia tests are influenced by the presence of acute thrombosis or anticoagulant therapy.[134]Stevens SM, Woller SC, Bauer KA, et al. Guidance for the evaluation and treatment of hereditary and acquired thrombophilia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016 Jan;41(1):154-64.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11239-015-1316-1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26780744?tool=bestpractice.com

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Antiphospholipid antibodies may predict a higher risk of future thrombosis following an initial VTE event and may impact selection of therapy.[62]Garcia D, Erkan D. Diagnosis and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24;378(21):2010-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29791828?tool=bestpractice.com

Controversy exists regarding whether broad screening for antiphospholipid antibodies or screening only on the basis of clinical suspicion should be preferred.[137]Fazili M, Stevens SM, Woller SC. Direct oral anticoagulants in antiphospholipid syndrome with venous thromboembolism: impact of the European Medicines Agency guidance. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020 Jan;4(1):9-12.

https://www.rpthjournal.org/article/S2475-0379(22)01960-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31989078?tool=bestpractice.com

Some guidelines suggest testing only in situations where the result is likely to change a clinical decision (such as in patients with unprovoked DVT or PE who are considering stopping anticoagulants; however, these guidelines recommend seeking specialist advice as these tests may be affected by anticoagulants).[19]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Venous thromboembolic diseases: diagnosis, management and thrombophilia testing. Aug 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng158

For antiphospholipid antibody screening, cardiolipin and beta-2 glycoprotein-I antibodies can be performed without regard to the presence of anticoagulants; however, most anticoagulants interfere with assays for lupus anticoagulant.[62]Garcia D, Erkan D. Diagnosis and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24;378(21):2010-21.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29791828?tool=bestpractice.com

Tests for underlying conditions

Occult cancer is present in approximately 3% to 5% of patients with an unprovoked DVT.[138]Timp JF, Braekkan SK, Versteeg HH, et al. Epidemiology of cancer-associated venous thrombosis. Blood. 2013 Sep 5;122(10):1712-23.

https://ashpublications.org/blood/article/122/10/1712/31702/Epidemiology-of-cancer-associated-venous

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23908465?tool=bestpractice.com

However, extensive investigations (beyond routine laboratory tests and age-appropriate routine screening) for cancer in patients with a first unprovoked DVT are not routinely indicated, because they have not been convincingly shown to improve prognosis or mortality.[139]Piccioli A, Lensing AW, Prins MH, et al; SOMIT Investigators Group. Extensive screening for occult malignant disease in idiopathic venous thromboembolism: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2004 Jun;2(6):884-9.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00720.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15140122?tool=bestpractice.com

[140]Prandoni P, Falanga A, Piccioli A. Cancer and venous thromboembolism. Lancet Oncol. 2005 Jun;6(6):401-10.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15925818?tool=bestpractice.com

[141]Carrier M, Lazo-Langner A, Shivakumar S, et al; SOME Investigators. Screening for occult cancer in unprovoked venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373(8):697-704.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1506623

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26095467?tool=bestpractice.com

[142]Robertson L, Broderick C, Yeoh SE, et al. Effect of testing for cancer on cancer- or venous thromboembolism (VTE)-related mortality and morbidity in people with unprovoked VTE. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Oct 1;(10):CD010837.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010837.pub5/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34597414?tool=bestpractice.com

Signs or symptoms that suggest a possible malignancy should be pursued, if present.

Pregnancy

Clinical suspicion of DVT in pregnant women is challenging due to the overlap of symptoms associated with pregnancy and thrombosis. Furthermore, there is a higher prevalence of iliac vein thrombosis in pregnant compared with nonpregnant patients that can render an accurate diagnosis even more challenging.[143]Chan WS, Spencer FA, Ginsberg JS. Anatomic distribution of deep vein thrombosis in pregnancy. CMAJ. 2010 Apr 20;182(7):657-60.

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/182/7/657

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20351121?tool=bestpractice.com

The D-dimer assay plays a limited role in pregnancy due to its natural rise with each trimester.[128]Francalanci I, Comeglio P, Liotta AA, et al. D-dimer concentrations during normal pregnancy, as measured by ELISA. Thromb Res. 1995 Jun 1;78(5):399-405.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7660356?tool=bestpractice.com

However, a negative D-dimer test may be useful in ruling out a diagnosis of DVT in these patients.[129]Chan WS, Chunilal S, Lee A, et al. A red blood cell agglutination D-dimer test to exclude deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Aug 7;147(3):165-70.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17679704?tool=bestpractice.com

The Wells score has not been validated in the pregnant population and, therefore, should not be routinely used to risk stratify a pregnant patient with a suspected DVT. A clinical prediction rule termed the LEFt score has been developed specifically for the pregnant population. This rule has yet to be rigorously validated and should not be used routinely.[119]Chan WS, Lee A, Spencer FA, et al. Predicting deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy: out in "LEFt" field? Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jul 21;151(2):85-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19620161?tool=bestpractice.com

The correct diagnosis will thus rely on a high index of suspicion and close follow-up. Venous DUS remains the initial test of choice for a pregnant woman suspected of having a DVT. Several studies investigating the role of a single, whole-leg ultrasound or serial, proximal compression ultrasonography for the diagnosis of DVT have been pooled in a meta-analysis.[144]Chan WS, Spencer FA, Lee AY, et al. Safety of withholding anticoagulation in pregnant women with suspected deep vein thrombosis following negative serial compression ultrasound and iliac vein imaging. CMAJ. 2013 Mar 5;185(4):E194-200.

https://www.cmaj.ca/content/185/4/E194

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23318405?tool=bestpractice.com

[145]Le Gal G, Prins AM, Righini M, et al. Diagnostic value of a negative single complete compression ultrasound of the lower limbs to exclude the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis in pregnant or postpartum women: a retrospective hospital-based study. Thromb Res. 2006;118(6):691-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16414102?tool=bestpractice.com

[146]Ratiu A, Navolan D, Spatariu I, et al. Diagnostic value of a negative single color duplex ultrasound in deep vein thrombosis suspicion during pregnancy. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2010 Apr-Jun;114(2):454-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20700985?tool=bestpractice.com

[147]Linnemann B, Bauersachs R, Rott H, et al. Diagnosis of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism - position paper of the Working Group in Women's Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH). Vasa. 2016;45(2):87-101.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27058795?tool=bestpractice.com

[148]Al Lawati K, Aljazeeri J, Bates SM, et al. Ability of a single negative ultrasound to rule out deep vein thrombosis in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Feb;18(2):373-80.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jth.14650

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31557394?tool=bestpractice.com

The false-negative rate of this approach is low, but the absolute number of patients enrolled in trials is modest. Due to a higher prevalence of isolated pelvic vein thrombi in these patients, guidelines also recommend a low threshold to obtain additional imaging (e.g., an iliac vein ultrasound or abdominal magnetic resonance venography) in patients with a suspected abdominal/pelvic vein thrombosis (i.e., swelling of the entire leg, or buttock or back pain).[27]Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(suppl 2):e351S-418S.

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60128-7/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315267?tool=bestpractice.com