Tuberous sclerosis complex

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

Treatment algorithm

Please note that formulations/routes and doses may differ between drug names and brands, drug formularies, or locations. Treatment recommendations are specific to patient groups: see disclaimer

renal cell carcinoma (suspected or confirmed)

kidney-sparing resection or total nephrectomy

If there is a suspicion of underlying carcinoma, kidney-sparing resection or total nephrectomy may be needed; the aim is to perform as limited a resection as possible. See Renal cell carcinoma (Management).

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice.

intracranial aneurysm

surgical/radiologic intervention

These lesions are very uncommon but, when present, may appear as elongated or segmental outpouchings from intracranial vessels. Flow voids on magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) may appear as enlargements or inhomogeneous signal intensity, if there is a mural clot.

Treatment can be through interventional radiologic means, such as with intra-arterial coiling procedures, or by neurosurgical intervention through open craniotomy and aneurysm clipping procedures. See Cerebral aneurysm (Management).

neurologic

anticonvulsant

The anticonvulsant vigabatrin is particularly effective for treating infantile spasms associated with TSC, and is recommended as first-line therapy.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com [50]Hancock EC, Osborne JP, Edwards SW. Treatment of infantile spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 5;(6):CD001770. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001770.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23740534?tool=bestpractice.com [51]van der Poest Clement E, Jansen FE, Braun KPJ, et al. Update on drug management of refractory epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Paediatr Drugs. 2020 Feb;22(1):73-84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912454?tool=bestpractice.com

A meta-analysis of vigabatrin efficacy reported a cessation rate of 95% in children with TSC.[52]Hancock E, Osborne JP. Vigabatrin in the treatment of infantile spasms in tuberous sclerosis: literature review. J Child Neurol. 1999 Feb;14(2):71-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10073425?tool=bestpractice.com The duration of treatment is undefined, but has been suggested to be 6 to 12 months. Adverse effects of vigabatrin include potential retinal toxicity associated with peripheral vision loss, which may correlate with total cumulative dose. Vigabatrin should only be used when the potential benefits outweigh the potential risk of vision loss; appropriate monitoring should be carried out.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [53]Pellock JM, Hrachovy R, Shinnar S, et al. Infantile spasms: a U.S. consensus report. Epilepsia. 2010 Oct;51(10):2175-89. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02657.x http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20608959?tool=bestpractice.com

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), synthetic ACTH, or prednisone may be added as second-line therapy if spasms do not abate within 2 weeks.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com ACTH, corticosteroids, topiramate, lamotrigine, valproate, and levetiracetam may be used as alternatives to vigabatrin, but are less effective.[52]Hancock E, Osborne JP. Vigabatrin in the treatment of infantile spasms in tuberous sclerosis: literature review. J Child Neurol. 1999 Feb;14(2):71-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10073425?tool=bestpractice.com

Exacerbation of generalized seizures, including infantile spasms, has been noted with the use of carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin.[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com

Adjunctive oral cannabidiol has been reported to reduce seizures in TSC patients with a history of infantile spasms.[55]Saneto R, Sparagana S, Kwan P, et al. Efficacy of add-on cannabidiol (CBD) treatment in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and a history of infantile spasms (IS): post hoc analysis of phase 3 trial GWPCARE6 (1534). Neurology. Apr 2021;96(suppl 15):1534. https://n.neurology.org/content/96/15_Supplement/1534 Use of oral cannabidiol is off-label for children younger than 1 year.

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice.

See Infantile spasms for more information.

Primary options

vigabatrin: 25 mg/kg orally twice daily initially, increase in increments of 25-50 mg/kg/day every 3 days according to response, maximum 150 mg/kg/day

More vigabatrinUse the lowest dose and shortest duration necessary to achieve clinical goals due to risk of vision impairment.

ketogenic diet or low glycemic index treatment

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

A ketogenic diet (which is high in fat and low in carbohydrate) or low glycemic index treatment may be an effective nonpharmacologic therapy for patients with infantile spasms that are refractory to vigabatrin and hormonal therapies.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com The ketogenic diet must be started in the hospital, under close medical supervision, with appropriate monitoring.

anticonvulsant

Anticonvulsant drug therapy should be based upon the specific seizure type(s), epilepsy syndrome(s) present, the patient's age, and adverse-effects profiles.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com [50]Hancock EC, Osborne JP, Edwards SW. Treatment of infantile spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 5;(6):CD001770. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001770.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23740534?tool=bestpractice.com

The long-term use of agents with potential sedating and mood-altering properties (benzodiazepines, barbiturates, levetiracetam) needs to be balanced against their potential utility.

Any anticonvulsant can be utilized judiciously.[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com

See Focal seizures, Generalized seizures in adults, and Generalized seizures in children for more information.

Exacerbation of generalized seizures, particularly myoclonic (infantile spasms) and atypical absence types, has been noted with the use of carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin.[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com These agents, however, are particularly beneficial in patients with focal seizures.

Cannabidiol oral solution is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of seizures associated with TSC in patients 1 year and older. In one double-blind randomized controlled trial, adjunctive cannabidiol significantly reduced TSC-associated seizures compared with placebo.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [56]Thiele EA, Bebin EM, Bhathal H, et al. Add-on cannabidiol treatment for drug-resistant seizures in tuberous sclerosis complex: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021 Mar 1;78(3):285-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33346789?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice.

everolimus

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

Adjunctive everolimus has been shown to reduce seizure frequency and to be well tolerated.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]French JA, Lawson JA, Yapici Z, et al. Adjunctive everolimus therapy for treatment-resistant focal-onset seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis (EXIST-3): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2016 Oct 29;388(10056):2153-63.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31419-2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27613521?tool=bestpractice.com

It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration as an adjunctive treatment for patients aged 2 years and older with refractory focal-onset seizures, with or without secondary generalization, associated with TSC. It reduces seizure frequency by at least 25%.[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

Primary options

everolimus (oncologic): consult specialist for guidance on dose

ketogenic diet or low glycemic index treatment

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

The ketogenic diet (which is high in fat and low in carbohydrate) or low glycemic index treatment may be an effective nonpharmacologic therapy for patients with TSC with intractable epilepsy. The diet must be started in the hospital, under close medical supervision, with appropriate monitoring.

early evaluation and provision of surgical interventions

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

Surgical options include focal and multifocal cortical resection, corpus callosotomy, and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS).[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com [54]Romanelli P, Verdecchia M, Curatolo P, et al. Epilepsy surgery for tuberous sclerosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2004 Oct;31(4):239-47. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15464634?tool=bestpractice.com [58]Jansen FE, van Huffelen AC, Algra A, et al. Epilepsy surgery in tuberous sclerosis: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2007 Aug;48(8):1477-84. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01117.x/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17484753?tool=bestpractice.com [59]Wang S, Fallah A. Optimal management of seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: current and emerging options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014 Oct 23;10:2021-30. https://www.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S51789 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25364257?tool=bestpractice.com

Each intervention will require careful and phased presurgical evaluation. Prolonged electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring via noninvasive telemetry and invasive intracranial telemetry, augmented by advanced neuroimaging techniques (MRI, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, single photon emission computed tomography, positive emission tomography [PET] scan), will be necessary to identify both the epileptogenic foci and the most appropriate neurosurgical intervention.

Focal and multifocal cortical resection of epileptogenic tubers and regions of cortical dysplasia has been successful, despite theoretical concerns regarding the activation of alternative foci.[54]Romanelli P, Verdecchia M, Curatolo P, et al. Epilepsy surgery for tuberous sclerosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2004 Oct;31(4):239-47. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15464634?tool=bestpractice.com

Corpus callosotomy has been most successful as an adjunctive treatment for atonic and tonic seizures. The procedure may help limit the generalization of focal-onset seizures, but does not eliminate their genesis.[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com Therefore seizure reduction is not always expected; rather, an alteration to a better-tolerated seizure semiology (focal) is anticipated.

Vagus nerve stimulation in patients with TSC offers the potential for long-term reduction in seizure frequency as a palliative procedure, and is a less invasive intervention.[59]Wang S, Fallah A. Optimal management of seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: current and emerging options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014 Oct 23;10:2021-30. https://www.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S51789 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25364257?tool=bestpractice.com

periodic neuroimaging

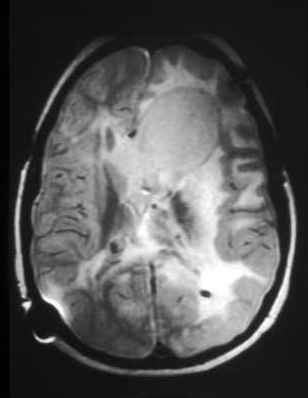

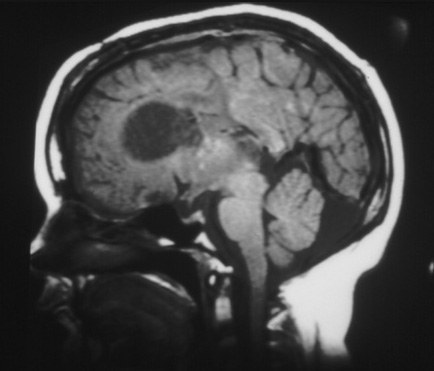

Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) lesions may be identified in prepubescent children. These have a propensity to enlarge, but not invariably so. The challenge clinically is identifying when to surgically resect these lesions before they become symptomatic.

Periodic neuroimaging to follow sequential growth rate and size, at 1- to 3-year intervals depending upon symptoms and clinical-radiographic findings, is recommended until age 25 years.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

surgical resection or mTOR inhibitor

If untreated, some lesions may grow into the ventricular system or into the adjacent frontal lobes and optic chiasm.

When lesions are confined to within the ventricles and are less than 2 to 3 cm in size, total extirpation is likely without difficulty. Medical therapy with sirolimus or everolimus may be used to induce tumor remission or size reduction before resection.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com [61]Roth J, Roach ES, Bartels U, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: diagnosis, screening, and treatment - recommendations from the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference 2012. Pediatr Neurol. 2013 Dec;49(6):439-44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24138953?tool=bestpractice.com Larger lesions or those with extension into the surrounding and adjacent parenchyma will more often result in a residual tumor and a need for continued surveillance.[81]Berhouma M. Management of subependymal giant cell tumors in tuberous sclerosis complex: the neurosurgeon's perspective. World J Pediatr. 2010 May;6(2):103-10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20490765?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines support the use of mTOR inhibitors as an alternative to surgery for patients with mild to moderate symptoms, or for patients with large symptomatic subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) for whom surgery is not suitable or who prefer medical treatment.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Roth J, Roach ES, Bartels U, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: diagnosis, screening, and treatment - recommendations from the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference 2012. Pediatr Neurol. 2013 Dec;49(6):439-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24138953?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Li M, Zhou Y, Chen C, et al. Efficacy and safety of mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogues) for tuberous sclerosis complex: a meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019 Feb 13;14(1):39.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1012-x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30760308?tool=bestpractice.com

Sustained, clinically significant responses (≥50% reduction in SEGA volume relative to baseline) to everolimus have been reported.[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[82]Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013 Jan 12;381(9861):125-32.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23158522?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Long-term use of everolimus in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: final results from the EXIST-1 study. PLoS One. 2016 Jun 28;11(6):e0158476.

https://www.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158476

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27351628?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

Sirolimus is a reasonable alternative to everolimus for treating SEGA, although it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice.

Primary options

everolimus (oncologic): consult specialist for guidance on dose

Secondary options

sirolimus: consult specialist for guidance on dose

ventriculoperitoneal shunting

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

Very large lesions may require cerebrospinal fluid diversion during surgery, as these lesions are quite vascular and intracranial bleeding during surgery is a possibility.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

skin lesions

topical sirolimus or laser therapy or excision

Annual skin examinations are recommended for children with TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Facial angiofibromas and collagen plaques typically increase in both size and number over time, and such changes may be rapid.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Facial angiofibromasCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Topical sirolimus is effective for treating facial angiofibromas (a proprietary formulation is FDA-approved for this indication for patients 6 years and older), and may improve other skin lesions, in patients with TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer Smaller and flatter skin lesions appear to respond better to topical sirolimus than do bulky lesions. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed to maintain benefit. Topical sirolimus is well tolerated, with no measurable systemic absorption and generally mild adverse effects.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer Smaller and flatter skin lesions appear to respond better to topical sirolimus than do bulky lesions. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed to maintain benefit. Topical sirolimus is well tolerated, with no measurable systemic absorption and generally mild adverse effects.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

Oral everolimus also has beneficial effects on skin lesions, but the risk of adverse effects is greater than with the use of topical sirolimus. Many patients show improvement in skin lesions while taking a systemic mTOR inhibitor for other manifestations of TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

Laser therapy is also an effective option for treating angiofibromas, especially if early intervention is needed, or for lesions that protrude or do not improve with topical treatment.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com Treatment may need to be repeated over time to maintain control of new growth. Surgical resection and dermabrasion are further options for larger lesions (>2 mm).[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Primary options

sirolimus topical: (0.2%) children ≥6 years of age and adults: apply to the affected area(s) twice daily for 12 weeks then re-evaluate need for continuing treatment, maximum 600 mg (2 cm)/day (children 6-11 years of age) or 800 mg (2.5 cm)/day (children ≥12 years of age and adults)

clipping

Associated nail deformity, local irritation, and the potential to bleed are reasons for intervention.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ungual fibromaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

The parent or caregiver can do the clipping. At times, professional intervention may be required, depending upon size, location, and patient cooperation.

surgery

If simple clipping is unsatisfactory, the primary treatment is a surgical resection.

renal

antihypertensive drug therapy

Hypertension should be assessed at least annually. Treatment of hypertension secondary to renal complications with an inhibitor of the renin-aldosterone-angiotensin system should be guided by specialist advice.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

surveillance

Treatment is expectant surveillance for the initial years after identification. Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen should be performed every 1 to 3 years.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

mTOR inhibitor

When an asymptomatic, growing AML becomes larger than 3 cm in diameter, treatment with an mTOR inhibitor is recommended as first-line therapy.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com [49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com [62]Li M, Zhou Y, Chen C, et al. Efficacy and safety of mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogues) for tuberous sclerosis complex: a meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019 Feb 13;14(1):39. https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1012-x http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30760308?tool=bestpractice.com

A trial of everolimus may be considered for adults (and possibly younger patients, although it is not approved for use in children). Everolimus has been reported to be effective in reducing AML volume and to be safe over approximately 4 years.[65]Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Mar 9;381(9869):817-24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23312829?tool=bestpractice.com [66]Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, et al. Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 Jan;31(1):111-9. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfv249 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26156073?tool=bestpractice.com

Sirolimus has also shown some efficacy for treating AMLs and is a reasonable alternative, although it is not approved for this indication.[67]Peng ZF, Yang L, Wang TT, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a systematic review. J Urol. 2014 Nov;192(5):1424-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24813310?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice

Primary options

everolimus (oncologic): consult specialist for guidance on dose

Secondary options

sirolimus: consult specialist for guidance on dose

embolization

Elective and selective embolization of the artery supplying a lesion 6 to 8 cm in size can result in lesion infarction and involution.

Larger lesions can be treated in the same way, but may require selective kidney-sparing resection.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

mTOR inhibitor

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

Everolimus may be considered for adults (and possibly younger patients, although it is not approved for use in children) as part of a multidisciplinary approach including embolization.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Sirolimus has also shown some efficacy for treating AMLs and is a reasonable alternative, although it is not approved for this indication.[67]Peng ZF, Yang L, Wang TT, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a systematic review. J Urol. 2014 Nov;192(5):1424-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24813310?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice.

Primary options

everolimus (oncologic): consult specialist for guidance on dose

Secondary options

sirolimus: consult specialist for guidance on dose

kidney-sparing resection

Partial kidney-sparing resection may be performed if embolization is unsuccessful after repeated attempts, or if symptoms of hemorrhage, flank pain, or impaired renal function develop.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

mTOR inhibitor

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

Everolimus may be considered for adults (and possibly younger patients, although it is not approved for use in children) as part of a multidisciplinary approach including surgical resection.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Sirolimus has also shown some efficacy for treating AMLs and is a reasonable alternative, although it is not approved for this indication.[67]Peng ZF, Yang L, Wang TT, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a systematic review. J Urol. 2014 Nov;192(5):1424-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24813310?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice

Primary options

everolimus (oncologic): consult specialist for guidance on dose

Secondary options

sirolimus: consult specialist for guidance on dose

dialysis

Dialysis will be necessary if renal failure occurs.

Renal transplantation will ultimately be needed.

cardiovascular

antiarrhythmics

Treatment does not differ from usual treatment of arrhythmias, and should be guided by specialist advice.

Most often rhabdomyomas regress postpartum, but persistence can infrequently continue to produce preexcitation arrhythmias or outflow obstruction if large globular lesions protrude into the ventricular outflow tracts.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. Nonetheless, even large lesions are typically asymptomatic and do not require intervention.

Echocardiography should be carried out every 1 to 3 years for asymptomatic patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas, and more frequently for symptomatic patients, until regression is documented.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

pulmonary

mTOR inhibitor

Sirolimus is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), and is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with abnormal lung function.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com Sirolimus improved spirometric measurements and gas trapping, and stabilized lung function, in patients with LAM.[70]Gao N, Zhang T, Ji J, et al. The efficacy and adverse events of mTOR inhibitors in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018 Aug 14;13(1):134. https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-018-0874-7 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30107845?tool=bestpractice.com [71]Argula RG, Kokosi M, Lo P, et al. A novel quantitative computed tomographic analysis suggests how sirolimus stabilizes progressive air trapping in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Mar;13(3):342-9. https://www.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-631OC http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26799509?tool=bestpractice.com

Everolimus may be used off-label for treating LAM; if the patient is already taking everolimus for other indications, continued treatment with everolimus and monitoring with serial pulmonary function tests, rather than switching to sirolimus, is recommended.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com [70]Gao N, Zhang T, Ji J, et al. The efficacy and adverse events of mTOR inhibitors in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018 Aug 14;13(1):134. https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-018-0874-7 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30107845?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment with mTOR inhibitors does not appear to increase the incidence of respiratory infections in patients with LAM, and may even be protective.[72]Courtwright AM, Goldberg HJ, Henske EP, et al. The effect of mTOR inhibitors on respiratory infections in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2017 Jan 17;26(143):160004. https://www.doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0004-2016 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28096282?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment should be guided by specialist advice.

Primary options

sirolimus: consult specialist for guidance on dose

Secondary options

everolimus (oncologic): consult specialist for guidance on dose

oxygen and bronchodilator

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

Palliative intervention with supplemental oxygen and bronchodilator therapy may have limited benefit in selected cases.[74]Sullivan EJ. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a review. Chest. 1998 Dec;114(6):1689-703. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9872207?tool=bestpractice.com

lung transplant

Lung transplantation is generally required for end-stage lymphangioleiomyomatosis. However, even transplanted lungs may be at risk for recurrence due to benign cellular metastases from renal angiomyolipomas.[75]Karbowniczek M, Astrinidis A, Balsara BR, et al. Recurrent lymphangiomyomatosis after transplantation: genetic analyses reveal a metastatic mechanism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr 1;167(7):976-82. http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.200208-969OC http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12411287?tool=bestpractice.com

cognitive and behavioral

early educational support

A checklist for TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) has been developed and validated.[21]de Vries PJ, Whittemore VH, Leclezio L, et al. Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) and the TAND Checklist. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Jan;52(1):25-35. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.004 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25532776?tool=bestpractice.com [22]Leclezio L, Jansen A, Whittemore VH, et al. Pilot validation of the tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) checklist. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Jan;52(1):16-24. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.006 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25499093?tool=bestpractice.com TAND checklist Opens in new window Yearly monitoring for the features of TAND and their impact on daily life is recommended, with more frequent monitoring if appropriate.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com Further detailed evaluations are suggested if initial screening identifies a concern.

Repeated detailed screening is suggested at a number of time points: during the first 3 years of life (0-3 year evaluation), preschool (3-6 year evaluation), before middle school entry (6-9 year evaluation), during adolescence (12-16 year evaluation), and in early adulthood (18-25 year evaluation); and then as needed.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Early intervention and special education programs will need to be provided to support the individual child. Ongoing reassessment and program adjustment through school, in conjunction with a vocational needs assessment and community support systems placements, should be planned. Psychological and social support should be provided to families and caregivers.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

specialist referral and treatment

Treatment recommended for SOME patients in selected patient group

There are currently no TSC-specific interventions for any manifestations of TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND). Early specialist referral is required, and evidence-based nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment strategies for specific disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and anxiety disorders) should be used, personalized to the TAND profile of each patient.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com [76]Muzykewicz DA, Newberry P, Danforth N, et al. Psychiatric comorbid conditions in a clinic population of 241 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2007 Dec;11(4):506-13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17936687?tool=bestpractice.com

Choose a patient group to see our recommendations

Please note that formulations/routes and doses may differ between drug names and brands, drug formularies, or locations. Treatment recommendations are specific to patient groups. See disclaimer

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer