Tests

Tests to consider

genetic testing

Test

Used to establish a diagnosis if clinical criteria are unclear, and for family planning purposes for parents who have an affected child. Identification of a pathogenic variant in the TSC1 or TSC2 gene is sufficient for diagnosis or prediction of TSC irrespective of clinical findings.[1][4]

Genotyping may be carried out by blood testing, or by analysis of a buccal swab, saliva, or tissue samples.

No pathogenic TSC1 or TSC2 mutation is detected by conventional genetic testing in 10% to 15% of patients with TSC.[1][4][13][14]

If there are existing genetic test results, do not order a duplicate test unless there is uncertainty about the existing result, for example, the result is inconsistent with the patient’s clinical presentation or the test methodology has changed.[20]

Result

mutation of TSC1 or TSC2 gene

brain MRI

Test

MRI is able to detect more abnormalities than CT or ultrasound, and is the preferred imaging modality. Performed at diagnosis and every 1 to 3 years until age 25 years.[1]

Contrast agents should be avoided for brain MRI unless there is a growing lesion or clinical suspicion of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA).[1]

If MRI cannot be performed or is not available, CT or ultrasound (in neonates and infants with open fontanels) may be performed instead.[1]

Cortical tubers occur in 85% to 95% of patients, and are composed of both glial and neuronal cells with dysplastic cells of mixed lineage (giant cells). These cellular components are aligned in irregular lamina and anomalous columnar orientation with overlying cortical dysplasia. They are multiple, and are found at the gray-white junction as high-signal-intensity lesions on T2-weighted and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences on MRI. The MRI lesion characteristics in infants <3 months old, however, are hyperintense on T1-weighted and hypointense on T2-weighted images. Tubers may be found in the cerebellum, as well as in the cerebrum, without lobar predilection. A greater number of tubers correlates with greater cognitive/behavioral impairments.[2][3][26]

Subependymal nodules are identifiable adjacent to the ventricular wall as small protrusions into the cerebrospinal fluid cavity. These are often calcified by infancy, but this calcification may evolve more gradually over childhood. The nodules are composed of dysplastic astrocytes and mixed lineage astrocytic components.[2][3][26]

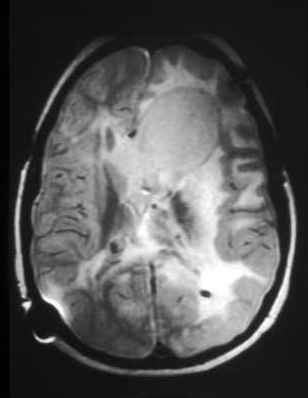

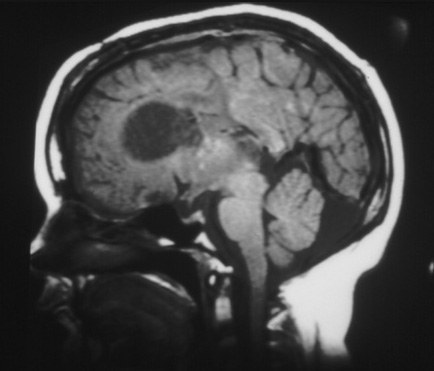

SEGAs occur in as many as 10% to 15% of TSC patients, usually by 10 years of age. Enlargement may produce obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid pathways and invasion into the underlying hypothalamic and chiasmatic region. It is not possible to predict the rate of growth and impending need for neurosurgical intervention. Follow-up imaging and clinical judgment are required.[2][3][26][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Result

calcified subependymal nodules, tubers, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, cortical dysplasia, migration lines

neurodevelopmental assessment

Test

Comprehensive assessment of TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) should be carried out at diagnosis using a validated screening tool such as the TAND checklist.[1][21][22] TAND checklist Opens in new window

Screening for TAND is then carried out annually, with more comprehensive formal evaluation during infancy, preschool, pre-middle school, adolescence, early adulthood, and thereafter as needed.[1][14]

Result

impaired cognitive functioning, with diminished developmental level and IQ

electroencephalogram (EEG)

Test

EEG with both asleep and awake phases is performed at diagnosis for all children with TSC, and as indicated for follow-up and management.[1]

An abnormal EEG should be followed up with an 8- to 24-hour video-EEG assessment, especially if features of TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) are present.[1]

Infantile spasms are associated with hypsarrhythmia (severe background disorganization with high-amplitude spike discharges and interruptions of activity called electrodecrements).

Result

spike discharges, abnormalities associated with seizures, hypsarrhythmia pattern with infantile spasms

ECG

Test

Performed at diagnosis, every 3 to 5 years in asymptomatic patients, and as indicated for follow-up.[1]

Result

premature atrial and ventricular contractions, arrhythmia, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

echocardiography

Test

Performed at diagnosis for all children, especially those younger than 3 years, and for adults with cardiac symptoms or a concerning medical history.

Also performed as indicated for follow-up of cardiac dysfunction and every 1 to 3 years in asymptomatic patients until regression of cardiac rhabdomyomas is documented.[1]

Rhabdomyomas affect 50% to 60% of TSC patients. Among infants with multiple lesions, 80% are ultimately diagnosed with TSC.[41] These lesions may be identified from 22 weeks of gestation. Most patients have a mean of 3 lesions, 3 to 25 mm in size, but rarely larger. They are identified in the ventricles more often than the atria, and in the septum more often than the walls.

Symptoms (arrhythmias, outflow obstruction, thromboembolism) are rare and are typically evident in the neonatal period.

These lesions generally regress during early childhood without the need for intervention.[2][3][26]

Fetal echocardiography may be used to identify babies with rhabdomyomas identified via prenatal ultrasound who have a high risk of heart failure after delivery.[1]

Result

rhabdomyomas

abdominal MRI

Test

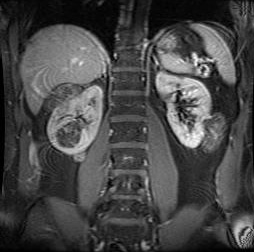

MRI detects more abnormalities than CT or ultrasound, and is the preferred imaging modality. Performed at diagnosis and every 1 to 3 years routinely; more frequent imaging should be performed as indicated for enlarging or symptomatic renal lesions.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on axial CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

CT may be used if MRI is contraindicated or unavailable.[1]

One large-scale study found that renal angiomyolipomas (AMLs) are reported in nearly 50% of patients, and in patients with ongoing renal AML, 88% exhibited multiple lesions, 84% had bilateral lesions, 33% had lesions larger than 3 cm, and 21% had growing lesions.[28] One-quarter of patients also had renal cysts.[28]

AMLs increase in size and number over life, whereas cysts may regress. Multiple cysts are similar to polycystic kidney disease, with the cysts made up of hypertrophic eosinophilic epithelial cells. The AMLs are made of a benign mix of blood vessels, smooth muscle, and fat. Rarely, there can be a malignant AML or renal cell carcinoma.[2][3][26]

Result

renal angiomyolipomas, renal cysts; may show aortic aneurysm or extrarenal hamartomas of liver, pancreas, or other abdominal organs

glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

Test

Measured at diagnosis, and then at least annually. Blood tests determine GFR using creatinine or cystatin C equations for adults or children.[1]

Result

impaired renal function

blood pressure

Test

Measured at diagnosis, and then at least annually.[1]

Result

secondary hypertension

high-resolution chest CT

Test

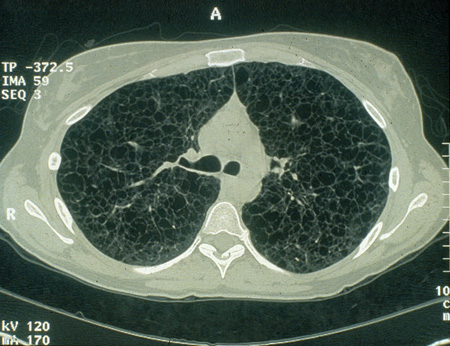

Performed for all women ages 18 years or older diagnosed with TSC to screen for the presence of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Repeat chest CT every 5 to 7 years in those with a negative screen who remain asymptomatic.[1][14] For patients with evidence of cystic lung disease consistent with LAM on screening chest CT, follow-up scan intervals should be determined on a case-by-case basis.[1]

Low-radiation protocols should be used when possible. Once cysts are detected, high-resolution chest CT testing should be obtained every 2 to 3 years to determine rate of progression. If rate of progression is advancing, testing can be performed every 3 to 6 months as needed.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cystic lesions in lymphangioleiomyomatosis of the lung (LAM) on axial CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Result

cystic cavitations of LAM of the lung, pneumothorax, chylothorax

pulmonary function tests and 6-minute walk test

Test

Baseline pulmonary function tests and 6-minute walk test should be carried out in patients with evidence of lung disease consistent with lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) on the screening CT.[1]

Also performed with chest CT to determine rate of progression of LAM.

Result

normal or decreased lung volume

skeletal x-ray

Test

Not routinely performed for diagnosis or clinical care. May be performed if symptoms/other historical factors suggest bone lesions.

Result

sclerotic bone lesions along the third and fourth metatarsals and vertebrae

colonoscopy

Test

Not routinely performed for diagnosis or clinical care. May be performed if symptoms/other historical factors suggest gastrointestinal polyps.

Result

intestinal hamartomatous polyps

renal biopsy

Test

Not routinely performed for diagnosis; used in select circumstances if malignancy is suspected.

Result

confirmation of suspected malignancy

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer