There is no cure for TSC. Treatment is aimed at the early identification of potentially progressive lesions, minimization of complications, and relief of symptoms.

mTOR inhibitors: everolimus and sirolimus

Everolimus and sirolimus act as negative regulators in cell signaling through the mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) pathway.[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

These compounds may effectively replace the deficient functioning of the tuberin-hamartin complex and reverse the unregulated cellular proliferation, faulty migration, and intracellular cell signaling defects that exist.

Everolimus is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adults with renal angiomyolipoma and TSC who do not require immediate surgery; for adults and children over 1 year who have subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) with TSC and require therapeutic intervention but who are not candidates for curative surgical resection; and for treatment of adults and children aged 2 years and older with TSC-associated focal-onset seizures. Oral sirolimus is FDA-approved for the treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and may be used off-label to treat some other features of TSC. Topical sirolimus is FDA-approved for the treatment of facial angiofibroma in patients with TSC ages 6 years and older.

Decisions about use of an mTOR inhibitor for treating a particular manifestation of TSC (e.g., SEGA) should take into account potential benefit for also treating any coexisting manifestations.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Neurologic

Seizures

Epilepsy is the most common presenting symptom of TSC and occurs in 90% of patients over a lifetime.[23]Holmes GL, Stafstrom CE; Tuberous Sclerosis Study Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex and epilepsy: recent developments and future challenges. Epilepsia. 2007 Apr;48(4):617-30.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01035.x/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17386056?tool=bestpractice.com

All seizure types may develop, with the exception of pure absence epilepsy. It most often becomes manifest in childhood, and infantile spasms may be the presenting symptom in one third of patients.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.[3]Hyman MH, Whittemore VH. National Institutes of Health consensus conference: tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Neurol. 2000 May;57(5):662-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10815131?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment options for seizures include anticonvulsants, cannabidiol, and everolimus.

Infantile spasms are the most potentially devastating epileptic complication of TSC, and are a risk factor for neurocognitive impairments and intellectual disability; earlier recognition and treatment of epilepsy is associated with better long-term neurologic outcomes.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com

Infantile Spasms Action Network: what does IS look like?

Opens in new window Electroencephalogram (EEG) should be performed for all children with TSC every 6 weeks up to age 12 months, and then every 3 months up to age 24 months.

The anticonvulsant vigabatrin is particularly effective for treating infantile spasms associated with TSC, and is recommended as first-line therapy.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Hancock EC, Osborne JP, Edwards SW. Treatment of infantile spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 5;(6):CD001770.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001770.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23740534?tool=bestpractice.com

[51]van der Poest Clement E, Jansen FE, Braun KPJ, et al. Update on drug management of refractory epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. Paediatr Drugs. 2020 Feb;22(1):73-84.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31912454?tool=bestpractice.com

A meta-analysis of vigabatrin efficacy reported a cessation rate of 95% in children with TSC.[52]Hancock E, Osborne JP. Vigabatrin in the treatment of infantile spasms in tuberous sclerosis: literature review. J Child Neurol. 1999 Feb;14(2):71-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10073425?tool=bestpractice.com

The duration of treatment is undefined, but has been suggested to be 6 to 12 months. Adverse effects of vigabatrin include potential retinal toxicity associated with permanent peripheral vision loss, which may correlate with total cumulative dose. Vigabatrin should only be used when the potential benefits outweigh the potential risk of vision loss; appropriate monitoring should be carried out.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Pellock JM, Hrachovy R, Shinnar S, et al. Infantile spasms: a U.S. consensus report. Epilepsia. 2010 Oct;51(10):2175-89.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02657.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20608959?tool=bestpractice.com

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), synthetic ACTH, or prednisone may be added as second-line therapy if infantile spasms do not abate within 2 weeks.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

ACTH, corticosteroids, topiramate, lamotrigine, valproate, and levetiracetam may be used as alternatives to vigabatrin, but are less effective.[54]Romanelli P, Verdecchia M, Curatolo P, et al. Epilepsy surgery for tuberous sclerosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2004 Oct;31(4):239-47.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15464634?tool=bestpractice.com

Adjunctive oral cannabidiol has been reported to reduce seizures in TSC patients with a history of infantile spasms.[55]Saneto R, Sparagana S, Kwan P, et al. Efficacy of add-on cannabidiol (CBD) treatment in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and a history of infantile spasms (IS): post hoc analysis of phase 3 trial GWPCARE6 (1534). Neurology. Apr 2021;96(suppl 15):1534.

https://n.neurology.org/content/96/15_Supplement/1534

Use of oral cannabidiol is off-label for children younger than 1 year.

See Infantile spasms for more information.

Choice of anticonvulsant treatment for seizures other than infantile spasms should be based on the specific seizure type(s), the epilepsy syndrome(s) present, the patient's age, and adverse-effect profiles of the medication.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Hancock EC, Osborne JP, Edwards SW. Treatment of infantile spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 5;(6):CD001770.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001770.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23740534?tool=bestpractice.com

The mTOR inhibitor everolimus and cannabidiol have been found in randomized controlled trials to be effective and well tolerated for treating seizures in patients with TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

See Focal seizures, Generalized seizures in adults, and Generalized seizures in children for more information.

Cannabidiol oral solution is FDA-approved for the treatment of seizures associated with TSC in patients 1 year and older. In one double-blind randomized controlled trial, adjunctive cannabidiol significantly reduced TSC-associated seizures compared with placebo. Doses used in clinical trials were equally efficacious; lower doses were associated with fewer adverse effects.[56]Thiele EA, Bebin EM, Bhathal H, et al. Add-on cannabidiol treatment for drug-resistant seizures in tuberous sclerosis complex: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021 Mar 1;78(3):285-92.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33346789?tool=bestpractice.com

Everolimus is FDA-approved as an adjunctive treatment for patients aged 2 years and older with refractory focal-onset seizures, with or without secondary generalization, associated with TSC. It reduces seizure frequency by at least 25%.[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer

A ketogenic diet (which is high in fat and low in carbohydrate) or low glycemic index treatment may be an effective nonpharmacologic therapy for patients with TSC with intractable epilepsy, including infantile spasms that are refractory to vigabatrin and hormonal therapies.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[57]Park S, Lee EJ, Eom S, et al. Ketogenic diet for the management of epilepsy associated with tuberous sclerosis complex in children. J Epilepsy Res. 2017 Jun;7(1):45-9.

https://www.j-epilepsy.org/journal/view.php?year=2017&vol=7&page=45

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28775955?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients can additionally benefit from the early evaluation and provision of surgical or neurostimulation interventions for epilepsy.[58]Jansen FE, van Huffelen AC, Algra A, et al. Epilepsy surgery in tuberous sclerosis: a systematic review. Epilepsia. 2007 Aug;48(8):1477-84.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01117.x/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17484753?tool=bestpractice.com

Options include focal and multifocal cortical resection, corpus callosotomy, and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS).[24]Thiele EA. Managing epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):680-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563014?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Romanelli P, Verdecchia M, Curatolo P, et al. Epilepsy surgery for tuberous sclerosis. Pediatr Neurol. 2004 Oct;31(4):239-47.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15464634?tool=bestpractice.com

[59]Wang S, Fallah A. Optimal management of seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: current and emerging options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014 Oct 23;10:2021-30.

https://www.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S51789

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25364257?tool=bestpractice.com

A systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical management of TSC in predicting seizure freedom summarized outcomes from 229 patients from 13 studies and found a pooled rate of postoperative seizure freedom to be 59%. Best outcomes were for patients whose seizures began after age 1 year, those who had unilateral focality on ictal or interictal electroencephalogram (EEG), and those who underwent lobectomy.[60]Zhang K, Hu WH, Zhang C, et al. Predictors of seizure freedom after surgical management of tuberous sclerosis complex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2013 Aug;105(3):377-83.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23523658?tool=bestpractice.com

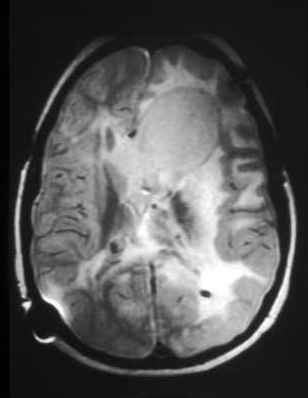

Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma

Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) lesions may be identified in prepubescent children. These have a propensity to enlarge, but not invariably so. The challenge clinically is identifying when to surgically resect these lesions before they become symptomatic. Periodic neuroimaging to follow sequential growth rate and size, at 1- to 3-year intervals depending upon symptoms and clinical-radiographic findings, is recommended until age 25 years.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

If untreated, some lesions may grow into the ventricular system or into the adjacent frontal lobes and optic chiasm.

If treatment is required, neurosurgical resection is indicated if possible for symptomatic SEGA. When lesions are confined to within the ventricles and are less than 2 to 3 cm in size, total extirpation is likely without difficulty. Medical therapy with sirolimus or everolimus may be used to induce tumor remission or size reduction before resection.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Roth J, Roach ES, Bartels U, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: diagnosis, screening, and treatment - recommendations from the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference 2012. Pediatr Neurol. 2013 Dec;49(6):439-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24138953?tool=bestpractice.com

Larger lesions or those with extension into the surrounding and adjacent parenchyma will more often result in a residual tumor and a need for continued surveillance. Very large lesions may require cerebrospinal fluid diversion as these lesions are quite vascular and intracranial bleeding during surgery is a possibility.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines support the use of mTOR inhibitors as an alternative to surgery for treatment of asymptomatic growing or large SEGA, for patients with mild to moderate symptoms, or for patients with large symptomatic SEGA for whom surgery is not suitable or who prefer medical treatment.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[61]Roth J, Roach ES, Bartels U, et al. Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: diagnosis, screening, and treatment - recommendations from the International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference 2012. Pediatr Neurol. 2013 Dec;49(6):439-44.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24138953?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Li M, Zhou Y, Chen C, et al. Efficacy and safety of mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogues) for tuberous sclerosis complex: a meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019 Feb 13;14(1):39.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1012-x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30760308?tool=bestpractice.com

Sustained, clinically significant responses (≥50% reduction in SEGA volume relative to baseline) to everolimus have been reported.[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer Sirolimus is a reasonable alternative to everolimus for treating SEGA, although it is not approved for this indication.

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer Sirolimus is a reasonable alternative to everolimus for treating SEGA, although it is not approved for this indication.

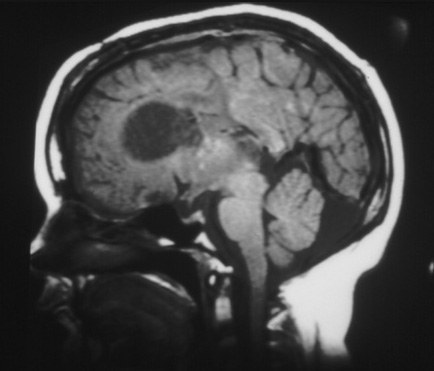

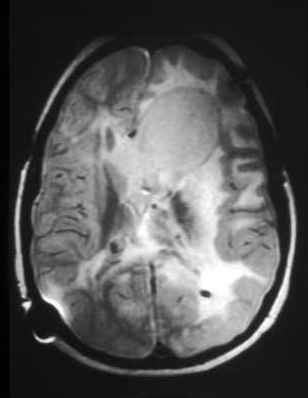

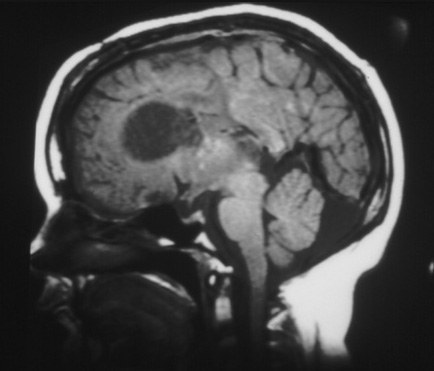

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (A-axial T2)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Skin lesions

Annual skin examinations are recommended for children with TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Angiofibromas and collagen plaques

Facial angiofibromas and collagen plaques typically increase in both size and number over time, and such changes may be rapid.

Topical sirolimus is effective for treating facial angiofibromas and other skin lesions in patients with TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer Smaller and flatter skin lesions appear to respond better to topical sirolimus than do bulky lesions. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed to maintain benefit. Topical sirolimus is well tolerated, with no measurable systemic absorption and generally mild adverse effects.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

]

What are the benefits and harms of rapamycin and rapalogs for people with tuberous sclerosis complex?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.4381/fullShow me the answer Smaller and flatter skin lesions appear to respond better to topical sirolimus than do bulky lesions. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed to maintain benefit. Topical sirolimus is well tolerated, with no measurable systemic absorption and generally mild adverse effects.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

Oral everolimus also has beneficial effects on skin lesions, but the risk of adverse effects is greater than with the use of topical sirolimus. Many patients show improvement in skin lesions while taking a systemic mTOR inhibitor for other manifestations of TSC.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

Laser therapy is also an effective option for treating angiofibromas, especially if early intervention is needed, or for lesions that protrude or do not improve with topical treatment.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment may need to be repeated over time to maintain control of new growth. Surgical resection and dermabrasion are further options for larger lesions (>2 mm).[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Facial angiofibromasCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Ungual fibromas

Ungual fibromas often become evident as a child enters early puberty, and are seen in 50% of adolescents and 75% of adults. They are slightly more common on the toes, but are found on the fingers as well. These are usually soft at first, but over time grow into hard lesions. They can be under, adjacent to, or at the base of the nail. If simple clipping is unsatisfactory, the primary treatment is a surgical resection. A small number of patients showed improvement when treated with either oral or topical sirolimus.[63]Nathan N, Wang JA, Li S, et al. Improvement of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) skin tumors during long-term treatment with oral sirolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Nov;73(5):802-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26365597?tool=bestpractice.com

[64]Egami A, Takahashi S, Kokubo T, et al. Topical sirolimus 0.2% gel for the management of tuberous sclerosis complex-related cutaneous manifestations: an interim analysis of postmarketing surveillance in Japan. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023 May;13(5):1113-26.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13555-023-00914-2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36905480?tool=bestpractice.com

Soft fibromas can also be found in the gingivae, but rarely interfere with dentition.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Ungual fibromaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Hypomelanotic macules and shagreen patches

Hypomelanotic macules and shagreen patches do not generally progress or cause symptoms, and therefore neither of these skin lesions require any specific intervention. Hypomelanotic macules may be evident at birth, or may become apparent over the first 1 to 2 years of life.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypomelanotic macules and shagreen patchCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Renal

Renal manifestations of TSC comprise angiomyolipomas (AMLs) or multiple cysts similar to polycystic kidney disease. Simple renal cysts do not require intervention. Malignant AML or renal cell carcinoma occur rarely. Most AMLs produce pain and hemorrhage in adulthood, whereas cysts are more likely to cause hypertension (treatable with antihypertensive drugs) and renal failure. Serious renal compromise occurs in <5% of patients overall.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.[3]Hyman MH, Whittemore VH. National Institutes of Health consensus conference: tuberous sclerosis complex. Arch Neurol. 2000 May;57(5):662-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10815131?tool=bestpractice.com

[26]DiMario FJ Jr. Brain abnormalities in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004 Sep;19(9):650-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15563010?tool=bestpractice.com

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen should be performed every 1 to 3 years for surveillance, and renal function and hypertension should be assessed at least annually.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

For a patient presenting with AML with acute hemorrhage, first-line therapy is embolization followed by corticosteroids.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Management of asymptomatic AML

When an asymptomatic, growing AML becomes larger than 3 cm in diameter, treatment with an mTOR inhibitor is recommended as first-line therapy.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[62]Li M, Zhou Y, Chen C, et al. Efficacy and safety of mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and its analogues) for tuberous sclerosis complex: a meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019 Feb 13;14(1):39.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13023-019-1012-x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30760308?tool=bestpractice.com

In a double-blind controlled trial of AMLs >3 cm in longest diameter, the response rate to everolimus was 42%, compared with 0% in the placebo group, over 8 months (with response defined as at least a 50% reduction in total AML volume).[49]Sasongko TH, Kademane K, Chai Soon Hou S, et al. Rapamycin and rapalogs for tuberous sclerosis complex. Cochrane database syst rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD011272.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011272.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37432030?tool=bestpractice.com

[65]Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Mar 9;381(9869):817-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23312829?tool=bestpractice.com

Everolimus treatment remained effective and safe over approximately 4 years, with the proportion of patients with AML reductions of ≥30% and ≥50% increasing over time.[66]Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, et al. Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 Jan;31(1):111-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfv249

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26156073?tool=bestpractice.com

Sirolimus has also shown some efficacy for treating AMLs and is a reasonable alternative, although it is not approved for this indication.[67]Peng ZF, Yang L, Wang TT, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a systematic review. J Urol. 2014 Nov;192(5):1424-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24813310?tool=bestpractice.com

Selective embolization or kidney-sparing resection are recommended second-line treatments for asymptomatic AMLs.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Elective and selective embolization of the artery supplying a lesion 6 to 8 cm in size can result in lesion infarction and involution. Larger lesions can be treated similarly or with selective kidney-sparing resection, if needed. Partial kidney-sparing resection may be performed if embolization is unsuccessful after repeated attempts, or if symptoms of hemorrhage, flank pain, or impaired renal function develop.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

If there is a suspicion of an underlying carcinoma, kidney-sparing resection or total nephrectomy may be needed; the aim is to perform as limited a resection as possible.

Management of secondary hypertension and deteriorating renal function

Treatment of hypertension secondary to renal complications with an inhibitor of the renin-aldosterone-angiotensin system should be guided by specialist advice.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

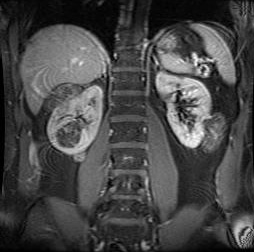

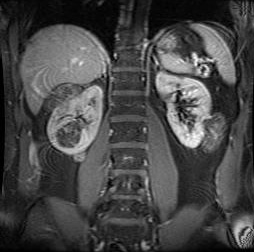

Dialysis will be necessary if deteriorating renal function secondary to AML(s) or polycystic renal disease is documented. Renal transplantation will ultimately be needed to restore renal function after renal failure has developed.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on axial CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Cardiovascular

Cardiac rhabdomyomas develop in utero, potentially causing arrhythmias due to their size or disruption of the normal conduction pathways. Fetal hydrops may result. Most often these lesions regress postnatally; echocardiography should be carried out every 1 to 3 years for asymptomatic patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas, and more frequently for symptomatic patients, until regression is documented.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Persistence can infrequently continue to produce preexcitation arrhythmias or outflow obstruction if large globular lesions protrude into the ventricular outflow tracts.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. If so, antiarrhythmic therapy can be used. However, even large lesions are typically asymptomatic and do not require intervention. There are some case reports of massive cardiac rhabdomyomas treated with everolimus over several months with a good response.[68]Nespoli LF, Albani E, Corti C, et al. Efficacy of everolimus low-dose treatment for cardiac rhabdomyomas in neonatal tuberous sclerosis: case report and literature review. Pediatr Rep. 2021 Mar 1;13(1):104-12.

https://www.mdpi.com/2036-7503/13/1/15/htm

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33804320?tool=bestpractice.com

Intracranial aneurysms are very uncommon but, when present, may appear as elongated or segmental outpouchings from intracranial vessels. Flow voids on magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) may appear as enlargements or inhomogeneous signal intensity, if there is a mural clot. Treatment for these lesions can be through interventional radiologic means, such as with intra-arterial coiling procedures, or by neurosurgical intervention through open craniotomy and aneurysm clipping procedures.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cardiac rhabdomyoma on sagittal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

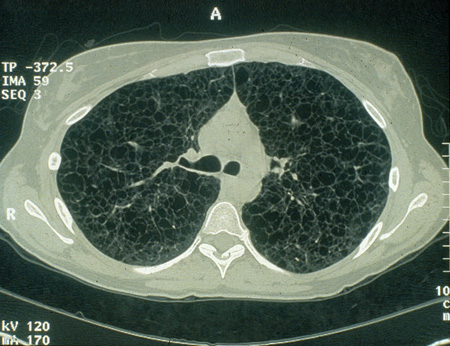

Pulmonary

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a disease identified both sporadically and in women with TSC.[69]McCarthy C, Gupta N, Johnson SR, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Nov;9(11):1313-27.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34461049?tool=bestpractice.com

It is unremitting and insidiously progressive, resulting in interstitial fibrosis and restrictive lung disease. The loss of normal lung elasticity results in decreased vital capacity, emphysematous chest expansion and ever-increasing pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, diminishing oxygenation, and increasing hypercapnia.

Adult women with TSC should be screened using chest computed tomography (CT) every 5 to 7 years for the presence of LAM. Follow-up scan intervals for women with LAM should be determined on a case-by-case basis.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Pulmonary function tests should be performed annually in patients with evidence of LAM.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Sirolimus is FDA-approved for treating LAM, and is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with abnormal lung function.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Sirolimus improved spirometric measurements and gas trapping, and stabilized lung function, in patients with LAM.[70]Gao N, Zhang T, Ji J, et al. The efficacy and adverse events of mTOR inhibitors in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018 Aug 14;13(1):134.

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-018-0874-7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30107845?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Argula RG, Kokosi M, Lo P, et al. A novel quantitative computed tomographic analysis suggests how sirolimus stabilizes progressive air trapping in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Mar;13(3):342-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-631OC

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26799509?tool=bestpractice.com

Everolimus may be used off-label for treating LAM; if the patient is already taking everolimus for other indications, continued treatment with everolimus and monitoring with serial pulmonary function tests, rather than switching to sirolimus, is recommended.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

[70]Gao N, Zhang T, Ji J, et al. The efficacy and adverse events of mTOR inhibitors in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018 Aug 14;13(1):134.

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-018-0874-7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30107845?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment with mTOR inhibitors does not appear to increase the incidence of respiratory infections in patients with LAM, and may even be protective.[72]Courtwright AM, Goldberg HJ, Henske EP, et al. The effect of mTOR inhibitors on respiratory infections in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2017 Jan 17;26(143):160004.

https://www.doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0004-2016

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28096282?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) has been shown to be a useful biomarker that correlates well with LAM disease severity and treatment response.[73]Young L, Lee HS, Inoue Y, et al. Serum VEGF-D concentration as a biomarker of lymphangioleiomyomatosis severity and treatment response: a prospective analysis of the Multicenter International Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Efficacy of Sirolimus (MILES) trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013 Aug;1(6):445-52.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3804556

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24159565?tool=bestpractice.com

Palliative intervention with supplemental oxygen and bronchodilator therapy may have limited benefit in selected cases.[74]Sullivan EJ. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a review. Chest. 1998 Dec;114(6):1689-703.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9872207?tool=bestpractice.com

Lung transplantation is generally required for end-stage LAM. However, even transplanted lungs may be at risk for recurrence due to benign cellular metastases from renal AMLs.[75]Karbowniczek M, Astrinidis A, Balsara BR, et al. Recurrent lymphangiomyomatosis after transplantation: genetic analyses reveal a metastatic mechanism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Apr 1;167(7):976-82.

http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.200208-969OC

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12411287?tool=bestpractice.com

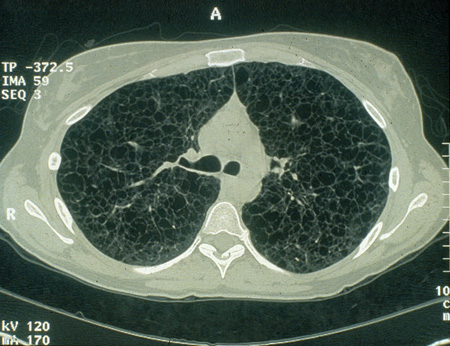

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Cystic lesions in lymphangioleiomyomatosis of the lung (LAM) on axial CTCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

Cognitive and behavioral

The cognitive and behavioral profiles of children and adults with TSC should be assessed periodically with standardized measures. In toddlers and preschool-aged children, specific attention to language and global cognitive ability is important. Autistic spectrum disorders and aggressive behaviors may be identified at this time.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[48]de Vries P, Humphrey A, McCartney D, et al. Consensus clinical guidelines for the assessment of cognitive and behavioural problems in tuberous sclerosis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Jul;14(4):183-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15981129?tool=bestpractice.com

A checklist for TSC-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) has been developed and validated.[21]de Vries PJ, Whittemore VH, Leclezio L, et al. Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) and the TAND Checklist. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Jan;52(1):25-35.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.004

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25532776?tool=bestpractice.com

[22]Leclezio L, Jansen A, Whittemore VH, et al. Pilot validation of the tuberous sclerosis-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) checklist. Pediatr Neurol. 2015 Jan;52(1):16-24.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.10.006

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25499093?tool=bestpractice.com

TAND checklist

Opens in new window Yearly monitoring for the features of TAND and their impact on daily life is recommended, with more frequent monitoring if appropriate.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

Further detailed evaluations are suggested if initial screening identifies a concern.

Repeated detailed screening is suggested at a number of time points: during the first 3 years of life (0-3 year evaluation), preschool (3-6 year evaluation), before middle school entry (6-9 year evaluation), during adolescence (12-16 year evaluation), and in early adulthood (18-25 year evaluation); and then as needed.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Amin S, Kingswood JC, Bolton PF, et al. The UK guidelines for management and surveillance of tuberous sclerosis complex. QJM. 2019 Mar 1;112(3):171-82.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy215

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30247655?tool=bestpractice.com

Neuropsychiatric specialty referral, interventions, and treatments should be instituted if indicated.

Behavioral problems can be managed with a combination of behavioral approaches and targeted psychopharmacology. Early intervention and special education programs will need to be provided in support of the individual child. Ongoing reassessment and program adjustment through school, in conjunction with a vocational needs assessment and community support systems placements, should be planned. Psychological and social support should be provided to families and caregivers.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

There are currently no TSC-specific interventions for any manifestations of TAND. Early specialist referral is required, and evidence-based nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment strategies for specific disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and anxiety disorders) should be used, personalized to the TAND profile of each patient.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]Muzykewicz DA, Newberry P, Danforth N, et al. Psychiatric comorbid conditions in a clinic population of 241 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2007 Dec;11(4):506-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17936687?tool=bestpractice.com

The use of mTOR inhibitors and their effectiveness for TAND is being investigated.[77]Franz DN, Capal JK. mTOR inhibitors in the pharmacologic management of tuberous sclerosis complex and their potential role in other rare neurodevelopmental disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 Mar 14;12(1):51.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13023-017-0596-2

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28288694?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]ClinicalTrials.gov. Trial of RAD001 and neurocognition in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01289912. Jan 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01289912

[79]ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of everolimus in the treatment of neurocognitive problems in tuberous sclerosis (TRON). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01954693. Jan 2018 [internet publication].

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01954693

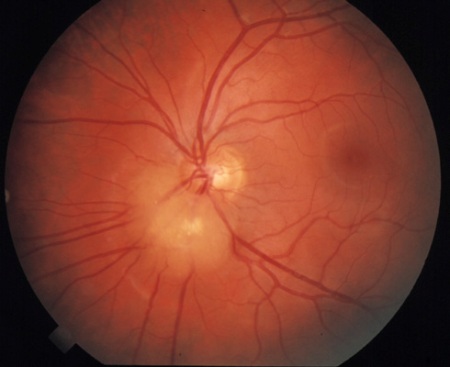

Eye lesions

Retinal hamartomas and vascular sheathing do not usually require treatment. These are mostly asymptomatic lesions that are nonprogressive over a lifetime. The hamartomas evolve such that calcification becomes apparent within them over time. Rare cases of aggressive lesions or of vision loss caused by the location of hamartomas have been reported, requiring intervention.[1]Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. 2021 Oct;123:50-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34399110?tool=bestpractice.com

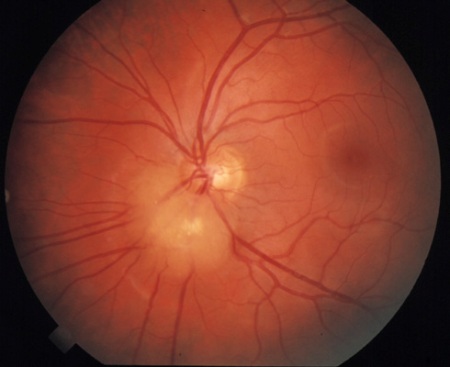

Hypopigmented patches of retina and eyelashes may also be found.[2]Gomez M, Sampson J, Whittemore V, eds. The tuberous sclerosis complex. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. Treatment is not required.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Retinal hamartomaCourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

]

]

]

]

]

Sirolimus is a reasonable alternative to everolimus for treating SEGA, although it is not approved for this indication.

]

Sirolimus is a reasonable alternative to everolimus for treating SEGA, although it is not approved for this indication. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Large subependymal giant cell astrocytoma on MRI (B-sagittal T1)Courtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

]

Smaller and flatter skin lesions appear to respond better to topical sirolimus than do bulky lesions. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed to maintain benefit. Topical sirolimus is well tolerated, with no measurable systemic absorption and generally mild adverse effects.[1][49]

]

Smaller and flatter skin lesions appear to respond better to topical sirolimus than do bulky lesions. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed to maintain benefit. Topical sirolimus is well tolerated, with no measurable systemic absorption and generally mild adverse effects.[1][49]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Multiple renal angiomyolipomas on coronal T1 MRICourtesy of Dr Francis J. DiMario Jr [Citation ends].