Approach

Characteristic history and physical exam findings are normally sufficient for the diagnosis of LSC.[17]

History

Presenting features

Although LSC is most common in women between 35 and 50 years of age, it can present in either sex and at any age, including during childhood.[1]

All patients report itching that, in most cases, is severe, intractable, worse at night, and exacerbated by heat, sweating, and clothing.[2] Nocturnal pruritus occurs only in the lighter stages of sleep.[18]

Paroxysmal pruritus, leading to intense scratching and rubbing, followed by a refractory period and then another attack of pruritus, defines the itch-scratch cycle characteristic of LSC.[1]

Patients commonly report that they cannot stop scratching and that it feels pleasurable to scratch.[2][19]

Patients not uncommonly report that the pruritus began during a time of stress, anxiety, or depression leading to an itch-scratch cycle.[2][9][8][20]

Medical history

A history of prior psychiatric disorder such as anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or dissociative experiences, or fibromyalgia may be elicited.[2][8][20][21]

Many patients reveal an atopic diathesis defined as a personal or immediate family history of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, or asthma.[2]

The presence of an underlying dermatosis such as atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, stasis dermatitis, superficial fungal (tinea and candidiasis) and dermatophyte infections, lichen sclerosis, viral warts, scabies, lice, an arthropod bite, or a cutaneous neoplasia should be determined.[1][2]

The presence of a systemic condition causing pruritus such as renal failure, obstructive biliary disease (primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis), Hodgkin lymphoma, hyper- or hypothyroidism, and polycythemia rubra vera should also be determined.

Physical exam

Single or multiple localized erythematous (in acute lesions) to violaceous (in chronic lesions) lichenified plaques, with variable overlying scale and erosion secondary to excoriation, are characteristic of LSC.[1][2] Another key feature of LSC is lichenification that results from chronic rubbing and scratching of the skin and is characterized by an exaggeration of normal skin markings, forming a crisscross mosaic pattern. Postinflammatory hyper- or, less commonly, hypopigmentation may be present in patients with darker skin, particularly with chronic lesions, as a result of the mechanical damage and necrosis, respectively, of melanocytes associated with chronic pruritus.[2] Linear fissures at sites of natural skinfolds (especially with genital involvement) may develop secondary to excoriation.[2]

LSC lesions are localized to specific areas of the body that are frequently manipulated. Although LSC can affect any body site, it most commonly involves the neck, ankles, scalp, vulva, pubis, scrotum, and extensor forearms.[1] Involvement of the shins or the interscapular back may result in lichen or macular amyloidosis, respectively.[4][5] Lichen amyloidosis is characterized by grouped hyperpigmented papules on the shins, while macular amyloidosis is characterized by a hyperpigmented, often lichenified, patch or plaque on the interscapular back associated with notalgia paresthetica.[4][5][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Secondary lichen simplex chronicus in the setting of atopic dermatitisFrom the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

Investigations

There is no specific test for the diagnosis of LSC. However, a skin biopsy can be performed if the history and physical exam findings are atypical or to exclude other similar-appearing dermatoses such as hypertrophic lichen planus, multiple keratoacanthomata, and pemphigoid nodularis.[1][22] Biopsy may also be useful in determining whether there is an underlying pruritic inflammatory dermatosis that may be driving secondary LSC. In addition, a skin biopsy may be indicated for lesions that do not show appropriate response to therapy to confirm the original diagnosis and exclude a cutaneous malignancy such as squamous cell carcinoma.

Investigations for the evaluation of the presence of an underlying systemic condition causing pruritus in secondary LSC may be warranted. These include:[1][2]

Patch testing for detection of a contact allergen in allergic contact dermatitis

A potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal cultures for the detection of fungal and dermatophyte infections, including vaginal fungal culture for patients with vulvar LSC[22]

Skin scrapings for the detection of scabies infestation

Serum TSH and free T4 levels for hyper- and hypothyroidism

Serum creatinine and BUN and electrolytes for renal failure

LFTs and gamma-GT for obstructive biliary disease (primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis)

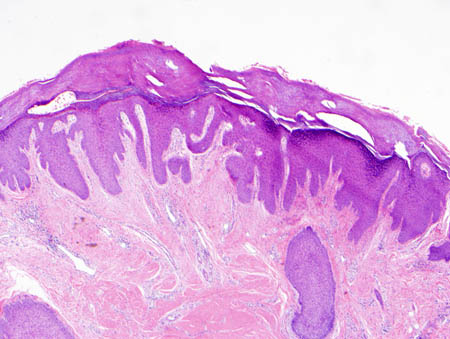

CBC for polycythemia rubra vera[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Low-power photomicrograph of lichen simplex chronicus (hematoxylin-eosin stain, x40)From the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

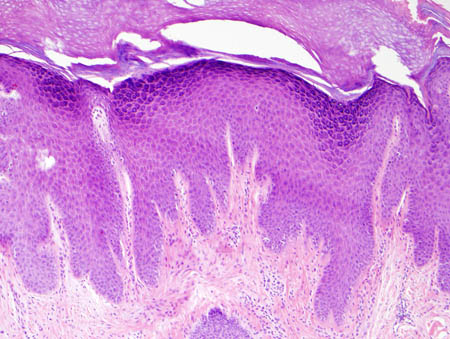

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medium-power photomicrograph of lichen simplex chronicus (hematoxylin-eosin stain, x100)From the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

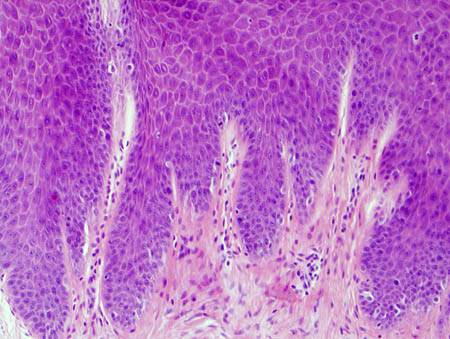

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medium-power photomicrograph of lichen simplex chronicus (hematoxylin-eosin stain, x100)From the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High-power photomicrograph of lichen simplex chronicus (hematoxylin-eosin stain, x200)From the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: High-power photomicrograph of lichen simplex chronicus (hematoxylin-eosin stain, x200)From the personal collection of Dr Brian L. Swick; used with permission [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer