Etiology

Bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses can penetrate the body's defense mechanisms and invade the cornea. Pathogens generally attack via the ocular surface; viruses such as herpes simplex virus may return through neuronal transport once the infection has been established.[3][4][12][13]

A key underlying predisposing factor for bacterial, fungal, Acanthamoeba, and viral keratitis is a compromised corneal epithelium. This can happen after overt ocular trauma, especially if a foreign body containing vegetable matter becomes lodged in the cornea. A compromised epithelium can also be caused by severe dry eyes, trichiasis (ingrown eyelashes), or corneal exposure from poor lid function. Epithelial erosions, such as those found in recurrent erosion syndrome or in various hereditary corneal dystrophies, also predispose to corneal infections. Blepharitis and conjunctivitis may increase contact with microbes and predispose to keratitis.[4]

Corneal ulcers and infiltrates are generally assumed to be bacterial, unless a high index of suspicion exists for another etiology. The most common causes of bacterial keratitis includePseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus,coagulase negative staphylococci,andStreptococcus pneumoniae.[3][4][5][6] They rely on a compromised corneal epithelium to cause infection. The species able to penetrate an intact epithelium are Neisseria species, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Haemophilus aegyptius, and Listeria species.[14] Mycobacteria and spirochetes are rare but may cause interstitial keratitis via hematogenous spread.

Fungal keratitis may be due to filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus and Fusarium species, or yeast, most commonly Candida albicans.[5][12]

Protozoal keratitis caused by Acanthamoeba species is an important corneal pathogen especially in contact lens wearers. Microsporidial keratitis can occur in immunocompromised patients.[5] Onchocerca species and Leishmania species cause interstitial keratitis in developing nations.

Viral keratitis is attributed to herpesviridae. Herpes simplex and herpes zoster represent the main causes, although cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus have also been implicated.[5]

Noninfectious keratitis etiologies

Keratitis can result from a number of noninfectious insults to the eye.[2][15][16][17]

Marginal keratitis: occurs secondary to the host's antibody response to the staphylococcal antigen present in cases of chronic blepharoconjunctivitis; self-limiting.

Exposure keratitis: due to dryness of the cornea caused by incomplete or inadequate eye-lid closure.

Photokeratitis: due to intense ultraviolet radiation exposure (e.g., snow blindness or welder's arc eye).

Allergic keratitis: a severe allergic response that may lead to corneal inflammation and ulceration (i.e., vernal keratoconjunctivitis).

Neurotrophic keratitis: a rare condition caused by damage (e.g., viral, surgical) to the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Characterized by absence of corneal sensitivity that renders the corneal surface vulnerable to occult injury and decreased reflex tearing.

Mooren ulcer: a rare inflammatory disorder of presumed autoimmune etiology consisting of peripheral corneal ulceration with a variable clinical course. Mooren ulcer is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Thygeson superficial punctate keratitis: characterized by a coarse punctate epithelial keratitis with little or no hyperemia of the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva of unknown etiology.

Diffuse lamellar keratitis: a rare complication of laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) surgery characterized by inflammatory infiltrates beneath the corneal flap interface.

Autoimmune keratitis: most commonly peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with systemic autoimmune disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, relapsing polychondritis, Behcet disease, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, or rosacea).

Pathophysiology

Microorganisms produce different clinical pictures depending on their toxins, virulence, invasiveness, adherence capabilities, and strain differences.[18] Corneal ulcer, the most common presentation of infectious keratitis, consists of a stromal infiltrate and necrosis with an overlying epithelial defect. Epitheliitis, in the form of punctate, dendritic, or geographic epithelial defects, is often associated with viral keratitis. Interstitial keratitis refers to stromal disease, whereas endotheliitis presents along with overlying stromal edema and keratic precipitates.

Healthy corneas are avascular, so the normal host defense mechanisms include physical barriers (e.g., eyelid and corneal epithelium, tear film turnover, as well as IgA, and other soluble macromolecules present in the tear film).[19] Once infection occurs, immune cells are recruited into the cornea from the tear film, limbal vasculature, and anterior chamber. Corneal vascularization can also occur, facilitating the entry of inflammatory cells, and mediators into the corneal stroma. Neighboring tissues are typically inflamed as well; lid edema, conjunctivitis, scleritis, and iridocyclitis (a form of anterior uveitis) may be seen. A hypopyon (a layered deposit of inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber) indicates a severe inflammatory reaction. While the inflammatory response may help to fight infection, the resulting release of tissue-destructive enzymes causes corneal scarring, necrosis, and thinning that lead to decreased vision in the long term and, in severe cases, perforation of the globe in the short term.

The pathogenesis of peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK), associated with systemic autoimmune disease, is believed to be associated with both T cell and antibody mediated pathways. It is presumed that T cells lead to antibody production and the formation of immune complexes that deposit in the peripheral cornea. Activation of the complement pathways, collagenases and proteases secreted by inflammatory cells leads to destruction of the peripheral corneal stroma. Histopathologic examination of cornea from patients with PUK showed evidence of inflammatory cells (plasma cells, neutrophils, mast cells, and eosinophils).[20]

Classification

Etiologic classification[1]

Bacterial keratitis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella, and Haemophilus influenzae are most common, but a wide range of species is documented.

Fungal keratitis: filamentous fungi (such as Fusarium species, Aspergillus species), and yeast ( Candida albicans).

Viral keratitis: herpes simplex, varicella zoster virus, cytomegalovirus (rare), Epstein-Barr virus (rare).

Protozoal: Acanthamoeba, Microsporidia (immunocompromised patients), Onchocerca (developing world), and Leishmania (developing world).

Causes of noninfectious keratitis include the following:[2]

Marginal keratitis

Exposure keratitis

Photokeratitis

Allergic keratitis

Neurotrophic keratitis

Mooren ulcer

Thygeson superficial punctate keratitis

Diffuse lamellar keratitis (a rare complication of LASIK surgery)

Autoimmune keratitis

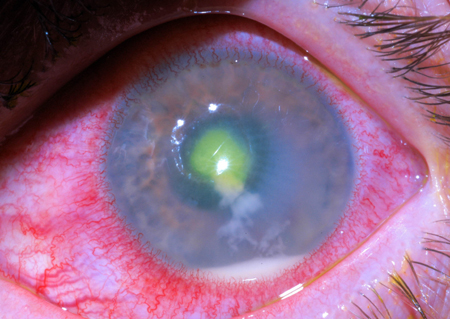

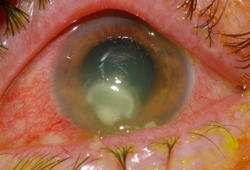

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bacterial corneal ulcer with hypopyonCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Moraxella corneal ulcerCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends].

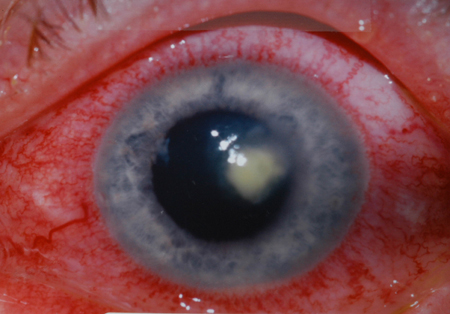

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Moraxella corneal ulcerCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fusarium corneal ulcer showing typical feathery edges and a satellite lesionCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends].

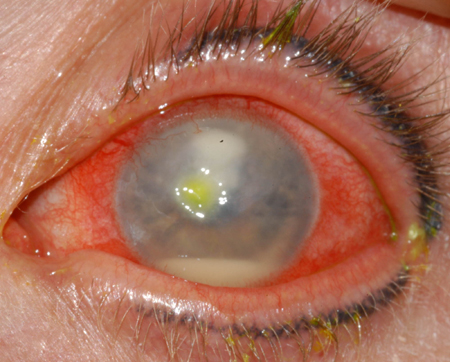

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fusarium corneal ulcer showing typical feathery edges and a satellite lesionCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fusarium keratitis with hypopyonCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends].

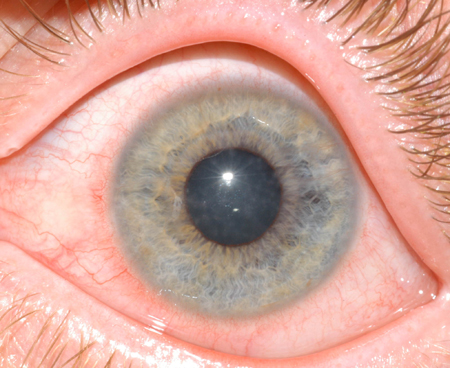

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Fusarium keratitis with hypopyonCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Early, superficial Acanthamoeba keratitisCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends].

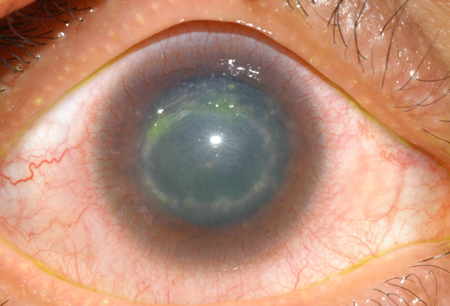

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Early, superficial Acanthamoeba keratitisCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A ring ulcer due to Acanthamoeba after start of treatmentCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A ring ulcer due to Acanthamoeba after start of treatmentCourtesy of F. I. Proctor Foundation, UCSF [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer