Approach

TR is most often found secondary to, or in association with, left-sided cardiac pathology in the form of advanced mitral, aortic, or left ventricular myocardial disorders.[1] The most commonly associated conditions include ischemic or degenerative mitral regurgitation. Other associated factors include a history of rheumatic heart disease, constrictive pericarditis, and permanent pacemaker placement. TR may be a consequence of endocarditis or carcinoid syndrome.TR rarely presents as an isolated disease process.

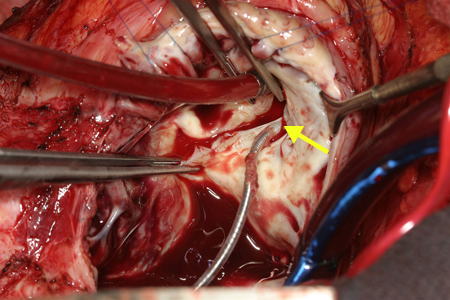

The pathological consequences of advanced TR are related to reduced cardiac output and right atrial hypertension. The clinical sequelae include atrial fibrillation, findings of advanced liver disease from chronic congestion or fibrosis (cardiac cirrhosis), and findings of congestive heart failure.[15][16][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Severe tricuspid regurgitation due to carcinoid valvular disease. A. Systolic frame from mid-esophageal 4 chamber view. Note thickened tricuspid leaflets, but also retracted and thickened chordae, typical of advanced carcinoid valvular disease (arrows). The right ventricle and right atrium are enlarged. The atrial septum is deviated to the left, demonstrating right atrial pressure is higher than left atrial pressure (asterisk). B. Color Doppler demonstrating severe tricuspid regurgitation. Vena contracta measured 1.2 cm, consistent with the coaptation gap on 2D images and virtually free flow between the right ventricle and right atrium.From the collection of Sorin V. Pislaru, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tricuspid valve entrapped with a pacemaker leadFrom the collection of Dr Thoraf M. Sundt III [Citation ends].

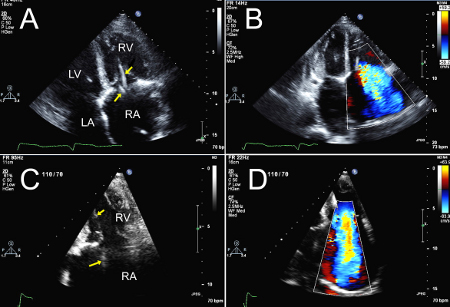

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Tricuspid valve entrapped with a pacemaker leadFrom the collection of Dr Thoraf M. Sundt III [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Two patients referred for severe tricuspid regurgitation after pacemaker implantation. A, C. Apical 4 chamber views (Mayo Clinic display format with right ventricle on the right) showing impingement of tricuspid leaflets by pacemaker leads (arrows). Note presence of two right ventricular leads in the first patient (panel A; one active, one abandoned lead). B, D. Corresponding Color Doppler images demonstrating severe tricuspid regurgitation due to lead impingement.From the collection of Sorin V. Pislaru, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Two patients referred for severe tricuspid regurgitation after pacemaker implantation. A, C. Apical 4 chamber views (Mayo Clinic display format with right ventricle on the right) showing impingement of tricuspid leaflets by pacemaker leads (arrows). Note presence of two right ventricular leads in the first patient (panel A; one active, one abandoned lead). B, D. Corresponding Color Doppler images demonstrating severe tricuspid regurgitation due to lead impingement.From the collection of Sorin V. Pislaru, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

History and examination

The clinical evaluation begins with a review of the patient’s history for conditions associated with tricuspid regurgitation, including left-sided heart failure, rheumatic heart disease, permanent pacemaker, endocarditis, and carcinoid heart disease.

The symptoms of left-sided cardiac disease predominate in most patients with secondary TR and include fatigue, effort intolerance, or dyspnea. Patients may describe palpitations due to atrial fibrillation or flutter.

Right heart failure can also be associated with TR. The clinical presentation involves exercise limitation, fatigue, and evidence of systemic venous congestion.[7][15] Additional signs and symptoms associated with right-sided heart failure include abdominal distention from ascites; liver pulsation due to advanced liver disease from chronic congestion or fibrosis (cardiac cirrhosis); gut congestion with symptoms of early satiety, dyspepsia, or indigestion; and fluid retention with leg swelling.[7]

The physical exam may note the following:

Irregular pulse.

Abnormal and prominent v wave in the jugular venous pulse.[7]

Lower left parasternal systolic murmur (holosystolic or less than holosystolic, depending on the severity of hemodynamic derangement). Increased systolic murmur on inspiration (Carvallo sign) may be present.[7]

Peripheral edema.

Pulsatile liver.

Investigations

Diagnosis of TR is most often made with a transthoracic echocardiogram, which assesses the structure and motion of the tricuspid valve, measures annular size, and identifies other cardiac abnormalities that might influence tricuspid valve function.[5] Systolic pulmonary artery pressure >55 mmHg is likely to cause TR with anatomically normal tricuspid valves, whereas TR occurring with systolic pulmonary artery pressures <40 mmHg likely reflects a structural abnormality of the valve apparatus. Functional or secondary TR is characterized by annular dilation, the extent of which may determine its severity.[1] Doppler echocardiography permits estimation of the severity of TR and right ventricle systolic pressure. A transesophageal echocardiogram can be performed if the transthoracic approach does not yield adequate quality images for accurate assessment.

ECG is routinely used to test for atrial flutter or fibrillation, or the presence of a previous myocardial infarction, and as part of preoperative assessment.

Liver function tests, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, and complete blood count (for anemia and thrombocytopenia) are used to assess renal and liver abnormalities.

Chest x-ray, to assess for heart failure and enlargement, will also show the presence of a pacemaker and/or pericardial effusion.

Cardiac catheterization is rarely required to establish or confirm TR, but is still useful for assessment of pulmonary artery pressures, heart hemodynamics, and coronary artery disease.[5]

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is seldom required. However, it is the preferred technique for assessment of right ventricular function, and is important for those patients in whom right heart function is a determinant of operability.

Intraoperative assessment

The effects of monitored anesthesia on cardiac hemodynamics will often falsely lower the magnitude of TR. For this reason, transesophageal echocardiography is not used to assess the degree of TR; however, it is accurate in determining tricuspid annular size.

Transesophageal echocardiography has become the standard intraoperative tool for valve operation and, for the most part, provides excellent intraoperative assessment of results.

Postoperative assessment

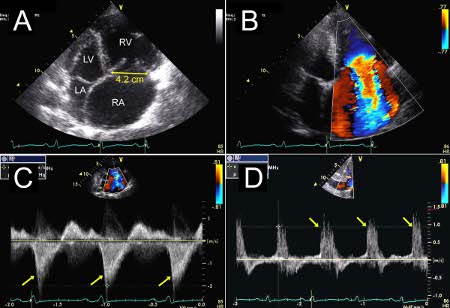

Transthoracic echocardiography is also the standard tool for valve assessment after operation. It is accurate and noninvasive.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Severe tricuspid regurgitation due to annular enlargement. A. Systolic frame from apical 4 chamber view (Mayo Clinic display format with right ventricle on the right). Note tricuspid annular enlargement measuring 4.2 cm and tethering of the tricuspid leaflets leading to failure of coaptation of the tricuspid valve. B. Massive tricuspid regurgitation on Color Doppler. C. Continuous Wave Doppler through the tricuspid valve. Note the dagger-shaped tricuspid regurgitant signal (arrows), consistent with rapid equalization of pressures between right ventricle and right atrium, typical of massive tricuspid regurgitation. D. Pulsed Wave Doppler of the hepatic veins demonstrates late systolic flow reversals consistent with severe tricuspid regurgitation.From the collection of Sorin V. Pislaru, Mayo Clinic [Citation ends].

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer