Most women with endometrial cancer present with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding (PVB).[21]Clarke MA, Long BJ, Del Mar Morillo A, et al. Association of endometrial cancer risk with postmenopausal bleeding in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sep 1;178(9):1210-22.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2695509

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30083701?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients are initially investigated with a pelvic (transvaginal) ultrasound. If there are suspicious findings on ultrasound, such as endometrial thickening or intrauterine mass, patients are referred for biopsy and/or dilation and curettage (D&C) for histologic evaluation and diagnosis.[94]Renaud MC, Le T. Clinical practice guideline no. 291 - epidemiology and investigations for suspected endometrial cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 Sep;40(9):e703-11.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30268319?tool=bestpractice.com

If a diagnosis is established, the patient is referred to a gynecologic oncologist or a general gynecologist with experience in endometrial cancer surgery. Appropriate referral should be made as soon as possible.[95]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. Aug 2023 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12

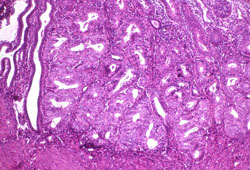

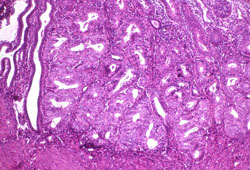

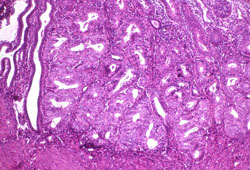

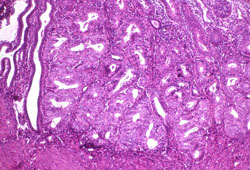

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histologic subtype: endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma, the commonest subtype; diagnosed on dilation and curettage in a patient presenting with postmenopausal bleeding (photomicrograph, hematoxylin and eosin stain)Courtesy of Professor Robert H. Young, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital [Citation ends].

Clinical history

The history should include determination of risk factors for endometrial cancer, including family history of cancer.

Genetic risk evaluation, including counseling and genetic testing, is recommended for women with a blood relative with a known Lynch syndrome pathogenic variant or a strong family history of endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, and/or ovarian cancer.[74]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: colorectal cancer [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[96]Saso S, Chatterjee J, Georgiou E, et al. Endometrial cancer. BMJ. 2011 Jul 6;343:d3954.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21734165?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Braun MM, Overbeek-Wager EA, Grumbo RJ. Diagnosis and management of endometrial cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Mar 15;93(6):468-74.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2016/0315/p468.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26977831?tool=bestpractice.com

Other risk factors strongly associated with endometrial cancer include being overweight/obese, age >50 years, diabetes mellitus, tamoxifen use, unopposed endogenous estrogen (e.g., anovulation), unopposed exogenous estrogen (e.g., estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy [HRT]), polycystic ovary syndrome, and radiation therapy.[96]Saso S, Chatterjee J, Georgiou E, et al. Endometrial cancer. BMJ. 2011 Jul 6;343:d3954.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21734165?tool=bestpractice.com

[97]Braun MM, Overbeek-Wager EA, Grumbo RJ. Diagnosis and management of endometrial cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Mar 15;93(6):468-74.

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2016/0315/p468.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26977831?tool=bestpractice.com

Direct questions should be asked about vaginal bleeding to establish that no other obvious cause could be responsible for PVB (e.g., intercourse, HRT, urinary source) and that the symptom is unlikely to be due to another genital tract malignancy, such as cervical cancer.

Patients should be asked about symptoms of abdominal or inguinal mass, abdominal distension, persistent pain (especially in the abdomen or pelvic region), fatigue, diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, persistent cough, shortness of breath, swelling, or weight loss, and new-onset neurologic symptoms. These symptoms may suggest extrauterine disease/metastases. The vagina, ovaries, and lungs are the most common metastatic sites.[7]Koskas M, Amant F, Mirza MR, et al. Cancer of the corpus uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Oct;155 Suppl 1(suppl 1):45-60.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13866

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34669196?tool=bestpractice.com

Premenopausal women

In premenopausal women who develop endometrial cancer, the main complaint is abnormal menstruation or abnormal vaginal bleeding, which may range from simple menorrhagia to a completely disorganized bleeding pattern. For this reason, premenopausal women with abnormal menstruation or vaginal bleeding often have an endometrial biopsy to rule out endometrial cancer, especially if they are ages >35 years. One systematic review found that the risk of endometrial cancer in premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding was 0.33%.[98]Pennant ME, Mehta R, Moody P, et al. Premenopausal abnormal uterine bleeding and risk of endometrial cancer. BJOG. 2017 Feb;124(3):404-11.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.14385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27766759?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical exam

Physical examination is often challenging because of the prevalence of obesity in patients with endometrial cancer. A gynecologic examination bed may facilitate the pelvic examination.

A bimanual examination gives an idea of uterine size, may detect the presence of a uterine mass or fixed uterus, and also evaluates for adnexal mass. The vulva, vagina, and cervix need to be thoroughly inspected using a speculum to rule out other gynecologic causes for the presenting symptoms.[99]Castellano T, Ding K, Moore KN, et al. Simple hysterectomy for cervical cancer: risk factors for failed screening and deviation from screening guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2019 Apr;23(2):124-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30817687?tool=bestpractice.com

Enlarged lymph nodes may be a sign of metastatic spread; however, nodal metastases are typically not diagnosed until surgery.

Investigations

Women presenting with PVB have a 5% to 10% risk of endometrial cancer; therefore, prompt evaluation with pelvic (transvaginal) ultrasound is warranted.[7]Koskas M, Amant F, Mirza MR, et al. Cancer of the corpus uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Oct;155 Suppl 1(suppl 1):45-60.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13866

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34669196?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Clarke MA, Long BJ, Del Mar Morillo A, et al. Association of endometrial cancer risk with postmenopausal bleeding in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Sep 1;178(9):1210-22.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2695509

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30083701?tool=bestpractice.com

[100]Gredmark T, Kvint S, Havel G, et al. Histopathological findings in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995 Feb;102(2):133-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7756204?tool=bestpractice.com

[101]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e124-9.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2018/05000/ACOG_Committee_Opinion_No__734__The_Role_of.40.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29683909?tool=bestpractice.com

Ultrasound

Pelvic (transvaginal) ultrasound can evaluate the endometrial thickness and uterine size and exclude a structural abnormality such as a polyp.[102]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: abnormal uterine bleeding. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69458/Narrative

Women with PVB with suspicious findings on ultrasound, such as a thickened endometrial stripe (>4 mm) or vascular mass, should undergo further investigation with biopsy and/or D&C for histologic confirmation of endometrial cancer.[101]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e124-9.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2018/05000/ACOG_Committee_Opinion_No__734__The_Role_of.40.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29683909?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histologic subtype: endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma, the commonest subtype; diagnosed on dilation and curettage in a patient presenting with postmenopausal bleeding (photomicrograph, hematoxylin and eosin stain)Courtesy of Professor Robert H. Young, Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital [Citation ends].

Saline infusion sonohysterography (an ultrasound procedure) can provide detailed imaging of the endometrium if routine pelvic ultrasound is inconclusive; however, it is not routinely used.[101]American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e124-9.

https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2018/05000/ACOG_Committee_Opinion_No__734__The_Role_of.40.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29683909?tool=bestpractice.com

It involves the transcervical injection of sterile fluid (e.g., normal saline) into the uterine cavity during real-time ultrasound scanning of the endometrium, which provides more detailed imaging than routine pelvic ultrasound.[103]American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Radiology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of sonohysterography. J Ultrasound Med. 2015 Aug;34(8):1-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26206817?tool=bestpractice.com

Biopsy

Office-based biopsy using an endometrial suction catheter (pipelle endometrial suction curette) is often the initial diagnostic step given its high sensitivity, low cost, and ready availability.[68]Ferguson SE, Soslow RA, Amsterdam A, et al. Comparison of uterine malignancies that develop during and following tamoxifen therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):322-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16352333?tool=bestpractice.com

[104]Larson DM, Johnson KK, Broste SK, et al. Comparison of D&C and office endometrial biopsy in predicting final histopathologic grade in endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Jul;86(1):38-42.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7784020?tool=bestpractice.com

[105]Huang GS, Gebb JS, Einstein, MH, et al. Accuracy of preoperative endometrial sampling for the detection of high-grade endometrial tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Mar;196(3):243.e1-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17346538?tool=bestpractice.com

The diagnostic accuracy of office-based biopsy can be improved by office hysteroscopy, if available.

If office-based biopsy is not technically feasible or cannot be tolerated by the patient, hysteroscopy and D&C under anesthesia is mandatory.

Molecular and genetic analysis

For women with endometrial cancer, guidelines recommend immunohistochemistry analysis for MMR status and/or testing for MSI status for all tumors. Further genetic evaluation should be carried out if the tumor is MMR deficient or MSI-high.[76]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: uterine neoplasms [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[77]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Testing strategies for Lynch syndrome in people with endometrial cancer. Oct 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg42

Immunohistochemistry can be carried out at initial biopsy or D&C, or on the final hysterectomy specimen. Further molecular profiling includes immunohistochemistry for p53 mutations and sequencing for POLE mutations.[19]Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013 May 2;497(7447):67-73. [Erratum in: Nature. 2013 Aug 8;500(7461):242.]

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature12113

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23636398?tool=bestpractice.com

[76]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: uterine neoplasms [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

[106]Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021 Jan;31(1):12-39.

https://ijgc.bmj.com/content/31/1/12

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33397713?tool=bestpractice.com

[107]Zhou X, Yao Z, Bai H, et al. Treatment-related adverse events of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitor-based combination therapies in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2021 Sep;22(9):1265-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34391508?tool=bestpractice.com

[108]Kommoss S, McConechy MK, Kommoss F, et al. Final validation of the ProMisE molecular classifier for endometrial carcinoma in a large population-based case series. Ann Oncol. 2018 May 1;29(5):1180-8.

29432521

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29432521?tool=bestpractice.com

Molecular analysis may be prognostic and guide treatment.[109]Jamieson A, McAlpine JN. Molecular profiling of endometrial cancer from TCGA to clinical practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023 Feb;21(2):210-6.

https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/21/2/article-p210.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36791751?tool=bestpractice.com

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) testing with a validated assay may be considered, especially for advanced or recurrent disease. Estrogen receptor testing should be carried out for stage III and IV, and recurrent tumors. HER2 immunohistochemistry testing is recommended for advanced and recurrent serous carcinoma or carcinosarcoma, and may be considered for p53-abnormal tumors. NTRK gene fusion testing may be considered for metastatic or recurrent disease.[76]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: uterine neoplasms [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

Pap smear

While a Pap smear is primarily used to screen for cervical dysplasia, in approximately 50% of cases it can identify abnormalities higher up in the genital tract and may be obtained initially.[110]Schnatz PF, Guile M, O'Sullivan DM, et al. Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells on cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Mar;107(3):701-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16507944?tool=bestpractice.com

Pap smear is not a screening test for endometrial cancer.

Uncommonly, women with undiagnosed endometrial cancer are found to have atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance on routine Pap smear cytology.[24]Gu M, Shi W, Barakat RR, et al. Pap smears in women with endometrial carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 2001 Jul-Aug;45(4):555-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11480718?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Eddy GL, Wojtowycz MA, Piraino PS, et al. Papanicolaou smears by the Bethesda system in endometrial malignancy: utility and prognostic importance. Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Dec;90(6):999-1003.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9397119?tool=bestpractice.com

Imaging studies for suspected extrauterine disease

Occasionally, the patient presentation may suggest the presence of extrauterine disease, and additional imaging (such as computed tomography [CT] of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or pelvic magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) may help in management planning.[111]Oaknin A, Bosse TJ, Creutzberg CL, et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022 Sep;33(9):860-77.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)01207-8/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35690222?tool=bestpractice.com

[112]American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: pretreatment evaluation and follow-up of endometrial cancer. 2020 [internet publication].

https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69459/Narrative

MRI has a limited role in preoperative assessment but may inform decision making in a patient who wants to pursue conservative management to maintain fertility, or to assess the feasibility of hysterectomy when there is suspicion that the cancer has invaded adjacent structures.

CT, MRI, or positron emission tomography (PET)/CT may be of value in the assessment of women with endometrial cancer who are not surgical candidates. These investigations can be used in the initial evaluation of disease; to monitor disease response to pharmacotherapy; and for surveillance, especially if recurrence is suspected.

Postoperative imaging

PET/CT may be helpful postoperatively to evaluate for gross residual disease, or in the post-treatment setting in differentiating recurrent or persistent tumor from fibrosis resulting from surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy.[113]Chang MC, Chen JH, Liang JA, et al. 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT for detection of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2012 Nov;81(11):3511-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22305013?tool=bestpractice.com

[114]Kitajima K, Murakami K, Yamasaki E, et al. Performance of FDG-PET/CT in the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2008 Mar 3;22(2):103-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18311534?tool=bestpractice.com

[115]Sharma P, Kumar R, Singh H, et al. Carcinoma endometrium: role of 18-FDG PET/CT for detection of suspected recurrence. Clin Nucl Med. 2012 Jul;37(7):649-55.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22691505?tool=bestpractice.com

[116]Kadkhodayan S, Shahriari S, Treglia G, et al. Accuracy of 18-F-FDG PET imaging in the follow up of endometrial cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Oct 26;128(2):397-404.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23107613?tool=bestpractice.com

However, it is costly and only sensitive for metastases.

Surgical staging

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) replaced clinical staging of endometrial cancer with surgical staging because clinical staging carries a large margin of error with regard to the true extent of disease.[6]Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009 May;105(2):103-4. [Erratum in: Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010 Feb;108(2):176.]

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19367689?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Koskas M, Amant F, Mirza MR, et al. Cancer of the corpus uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Oct;155 Suppl 1(suppl 1):45-60.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ijgo.13866

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34669196?tool=bestpractice.com

[117]Amant F, Mirza MR, Koskas M, et al. Cancer of the corpus uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Oct;143 Suppl 2:37-50.

https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijgo.12612

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30306580?tool=bestpractice.com

[118]Creasman WT, DeGeest K, DiSaia PJ, et al. Significance of true surgical pathologic staging: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Jul;181(1):31-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10411790?tool=bestpractice.com

Following staging surgery, surgical histopathology is performed to:[119]McMeekin DS, Filiaci VL, Thigpen JT, et al. The relationship between histology and outcome in advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer patients participating in first-line chemotherapy trials: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):16-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17574073?tool=bestpractice.com

[120]Cho KR, Cooper K, Croce S, et al. International Society of Gynecological Pathologists (ISGyP) endometrial cancer project: guidelines from the Special Techniques and Ancillary Studies Group. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019 Jan;38 Suppl 1:S114-22.

https://journals.lww.com/intjgynpathology/Fulltext/2019/01001/International_Society_of_Gynecological.9.aspx

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29521846?tool=bestpractice.com

Determine the extent of local and distant tumor spread

Confirm tumor grade and histology

Assess for the presence of prognostic factors such as depth of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, blood vessel microdensity, and cervical involvement.

Ancillary tests

A complete blood count early in the clinical work-up can evaluate for anemia and leukocytosis. Preoperative anemia and leukocytosis correlate with poor survival outcomes.[121]Abu-Zaid A, Alomar O, Abuzaid M, et al. Preoperative anemia predicts poor prognosis in patients with endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Mar;258:382-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33529973?tool=bestpractice.com

[122]Abu-Zaid A, Alomar O, Baradwan S, et al. Preoperative leukocytosis correlates with unfavorable pathological and survival outcomes in endometrial carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Sep;264:88-96.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34298450?tool=bestpractice.com

If a diagnosis of endometrial cancer is made, liver function tests can be used to screen for liver or bone metastases, and a chest x-ray for lung metastases. Chest x-ray has a low sensitivity for early lung metastases and may be substituted by chest CT.[123]Dinkel E, Mundinger A, Schopp D, et al. Diagnostic imaging in metastatic lung disease. Lung. 1990;168 Suppl:1129-36.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2117114?tool=bestpractice.com

[124]Davis SD. CT evaluation for pulmonary metastases in patients with extrathoracic malignancy. Radiology. 1991 Jul;180(1):1-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2052672?tool=bestpractice.com

Renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine) screen for obstructive uropathy.

CA-125 is a marker for serous or clear cell pathology, but is not often performed unless advanced disease is suspected.