Differentiated thyroid cancer: papillary, follicular, or oncocytic

Treatment of differentiated (papillary, follicular, oncocytic [previously known as Hürthle cell]) thyroid cancer depends on the extent of identifiable disease and the risk that unidentifiable disease foci are also present.[14]Cabanillas ME, McFadden DG, Durante C. Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2016 Dec 3;388(10061):2783-95.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27240885?tool=bestpractice.com

For patients with very low-risk tumors (e.g., unifocal papillary microcarcinomas [≤1 cm] with no evidence of extracapsular extension or lymph node metastases), active surveillance with ultrasound follow-up of the thyroid and neck lymph nodes every 6-12 months can be considered.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[66]Tuttle RM, Alzahrani AS. Risk stratification in differentiated thyroid cancer: from detection to final follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Mar 15;104(9):4087-100.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/104/9/4087/5380478

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30874735?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

[75]Saravana-Bawan B, Bajwa A, Paterson J, et al. Active surveillance of low-risk papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Surgery. 2020 Jan;167(1):46-55.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31526581?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidance does not routinely recommend FNA for a cytologic diagnosis on nodules less than 1 cm with low-risk features; however, this policy varies internationally, with some countries performing FNA and cytology for suspicious nodules before offering active surveillance.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[76]Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Oda H. Low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: a review of active surveillance trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018 Mar;44(3):307-15.

https://www.ejso.com/article/S0748-7983(17)30370-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28343733?tool=bestpractice.com

Active surveillance may be the preferred option in older patients and those at high surgical risk.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

Transitioning to surgery during active surveillance is indicated if the patient requests surgery or there are clinical changes (e.g., new biopsy-proven lymph node metastases; distant metastases; invasion into recurrent laryngeal nerve, trachea, or esophagus; radiologic evidence of extrathyroidal extension; cancer growth by 3 mm in any dimension or a 50% volume increase).[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[76]Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Oda H. Low-risk papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid: a review of active surveillance trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018 Mar;44(3):307-15.

https://www.ejso.com/article/S0748-7983(17)30370-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28343733?tool=bestpractice.com

For all other thyroid cancers, surgery is generally recommended for initial treatment.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

Total thyroidectomy is considered the standard surgical treatment. However, in patients with a tumor between 1 and 4 cm in diameter without extrathyroidal extension, and without clinical evidence of any lymph node metastases, lobectomy can be considered for the initial surgical procedure.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

It is important that patients understand that intraoperative findings during lobectomy may necessitate completion of a total thyroidectomy (completion thyroidectomy).[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Completion thyroidectomy for follicular and oncocytic thyroid carcinomas

Surgery (e.g., total thyroidectomy or lobectomy) is required to confirm (histologically) a diagnosis of follicular or oncocytic carcinoma because FNA cytology does not reliably distinguish between follicular or oncocytic adenoma (benign) and carcinoma.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

If invasive follicular or oncocytic carcinoma is diagnosed following initial lobectomy, then subsequent completion thyroidectomy may be required depending on the invasiveness of the tumor.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Completion thyroidectomy is required if a patient has invasive follicular or oncocytic carcinoma that is:[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

widely invasive (gross invasion of the thyroid gland with or without adjacent soft tissues and blood vessels), or

encapsulated angioinvasive with involvement of ≥4 blood vessels.

Disease monitoring is typically preferred in a patient with invasive follicular or oncocytic carcinoma that is: minimally invasive (encapsulated tumor with microscopic capsular invasion and without vascular invasion), or is encapsulated angioinvasive with involvement of <4 blood vessels.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Differentiated thyroid cancer: postsurgical thyroid hormone replacement therapy

Total thyroidectomy necessitates thyroid hormone replacement therapy (e.g., levothyroxine). As circulating thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) stimulates proliferation in normal thyrocytes and most thyroid cancer cells, TSH-suppressive doses of thyroid hormone therapy are used.[14]Cabanillas ME, McFadden DG, Durante C. Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2016 Dec 3;388(10061):2783-95.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27240885?tool=bestpractice.com

The use of thyroid hormone suppression should be based on initial risk of disease and ongoing risk assessment of disease status (see Diagnostic criteria for risk stratification). The lowest possible amount of thyroid hormone should be used.[77]Biondi B, Cooper DS. Thyroid hormone suppression therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2019 Mar;48(1):227-37.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30717904?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with high-risk disease, maintaining a serum TSH level of <0.1 mIU/L is recommended.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

Maintaining a serum TSH level of <0.1 mIU/L (but not necessarily undetectable) is also recommended in patients with residual structural disease or a biochemically incomplete response if they are young or at low risk of complications such as exogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[77]Biondi B, Cooper DS. Thyroid hormone suppression therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2019 Mar;48(1):227-37.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30717904?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with intermediate-risk disease, maintaining a serum TSH level of 0.1 to 0.5 mIU/L is recommended.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients with low-risk disease, serum TSH levels should be maintained in the low to normal range (0.5 to 2.0 mIU/L).[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

Patients with low-risk disease who have undergone lobectomy may not require thyroid hormone replacement therapy if their serum TSH is maintained in a low to normal target range.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

Differentiated thyroid cancer: complications of surgery and thyroid hormone replacement therapy

Complications of total thyroidectomy include an increased risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve damage or hypoparathyroidism.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

The risk of permanent hypoparathyroidism is higher for total than for subtotal thyroidectomy. The patient should be referred to an experienced surgeon.

TSH-suppressive doses of thyroid replacement therapy may result in exogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism, which in turn can result in adverse outcomes such as osteoporosis, fractures, and cardiovascular disease, including atrial fibrillation.[77]Biondi B, Cooper DS. Thyroid hormone suppression therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2019 Mar;48(1):227-37.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30717904?tool=bestpractice.com

Bone loss is of particular concern for TSH suppression in postmenopausal, non-estrogen-treated women, but the effect of TSH suppression on fracture rate is unclear.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]Brancatella A, Marcocci C. TSH suppressive therapy and bone. Endocr Connect. 2020 Jul;9(7):R158-72.

https://ec.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/ec/9/7/EC-20-0167.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32567550?tool=bestpractice.com

Differentiated thyroid cancer: central neck dissection

Therapeutic central neck dissection for patients with clinically involved central nodes should accompany total thyroidectomy to provide clearance of disease from the central neck.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

Prophylactic central neck dissection is controversial.[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

In some centers it is recommended, but the reduction in locoregional recurrence is accompanied by an increased rate of postoperative adverse effects.[79]Chen L, Wu YH, Lee CH, et al. Prophylactic central neck dissection for papillary thyroid carcinoma with clinically uninvolved central neck lymph nodes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2018 Sep;42(9):2846-57.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29488066?tool=bestpractice.com

Differentiated thyroid cancer: postsurgical radioactive iodine therapy

Risk assessment (based on surgical and pathologic findings) and assessment of postoperative disease status (including serum thyroglobulin [Tg] measurements and neck ultrasound) are required to guide selection of patients for radioactive iodine therapy.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[54]Webb RC, Howard RS, Stojadinovic A, et al. The utility of serum thyroglobulin measurement at the time of remnant ablation for predicting disease-free status in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis involving 3947 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Aug;97(8):2754-63.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/97/8/2754/2823340

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22639291?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, et al. Controversies, consensus, and collaboration in the use of (131)I therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: a joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2019 Apr;29(4):461-70.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2018.0597

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900516?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, et al. 2022 ETA consensus statement: what are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur Thyroid J. 2022 Jan 1;11(1):e210046.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/11/1/ETJ-21-0046.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34981741?tool=bestpractice.com

The use of radioactive iodine therapy is recommended following total thyroidectomy in patients with high-risk disease and in selected patients with intermediate-risk disease.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, et al. 2022 ETA consensus statement: what are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur Thyroid J. 2022 Jan 1;11(1):e210046.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/11/1/ETJ-21-0046.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34981741?tool=bestpractice.com

Radioactive iodine therapy is not routinely recommended for patients with low-risk disease, but features that impact on recurrence risk, disease follow-up implications, and patient preferences should be considered.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[82]Leboulleux S, Bournaud C, Chougnet CN, et al. Thyroidectomy without radioiodine in patients with low-risk thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022 Mar 10;386(10):923-32.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2111953

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35263518?tool=bestpractice.com

Selecting the optimal dose of therapeutic radioactive iodine can be challenging and should be based on risk assessment, and individualized (e.g., guided by patient factors and treatment goal).[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[81]Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, et al. 2022 ETA consensus statement: what are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur Thyroid J. 2022 Jan 1;11(1):e210046.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/11/1/ETJ-21-0046.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34981741?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, et al. Controversies, consensus, and collaboration in the use of (131)I therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: a joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2019 Apr;29(4):461-70.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2018.0597

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900516?tool=bestpractice.com

Consult local guidance.

Radioactive iodine therapy encompasses three overlapping treatment goals.[80]Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, et al. Controversies, consensus, and collaboration in the use of (131)I therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: a joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2019 Apr;29(4):461-70.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2018.0597

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900516?tool=bestpractice.com

Remnant ablation: to destroy postoperatively residual, presumably benign thyroid tissue to facilitate initial staging and follow-up studies

Adjuvant treatment: to destroy subclinical tumors after surgery to lower the risk of recurrence and improve survival

Treatment of known biochemical or structural disease.

Increased TSH levels are required to induce radioactive iodine uptake in thyroid cells.[81]Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, et al. 2022 ETA consensus statement: what are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur Thyroid J. 2022 Jan 1;11(1):e210046.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/11/1/ETJ-21-0046.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34981741?tool=bestpractice.com

Administration of exogenous recombinant human TSH (rhTSH) is the preferred method of preparation for radioactive iodine therapy for most patients.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Following radioactive iodine therapy, a whole-body radioactive iodine scan should be obtained to stage the disease and document the radioactive iodine avidity of any structural lesions.[73]Gulec SA, Ahuja S, Avram AM, et al. A joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the European Thyroid Association, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging on current diagnostic and theranostic approaches in the management of thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Jul;31(7):1009-19.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0826

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33789450?tool=bestpractice.com

Use of a "diagnostic" radioactive iodine scan following surgery, but before radioactive iodine therapy, is controversial.[81]Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, et al. 2022 ETA consensus statement: what are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur Thyroid J. 2022 Jan 1;11(1):e210046.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/11/1/ETJ-21-0046.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34981741?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, et al. Controversies, consensus, and collaboration in the use of (131)I therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer: a joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2019 Apr;29(4):461-70.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2018.0597

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30900516?tool=bestpractice.com

A diagnostic radioactive iodine scan may yield information relevant to clinical decision-making in selected patients only.[73]Gulec SA, Ahuja S, Avram AM, et al. A joint statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the European Thyroid Association, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging on current diagnostic and theranostic approaches in the management of thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Jul;31(7):1009-19.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0826

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33789450?tool=bestpractice.com

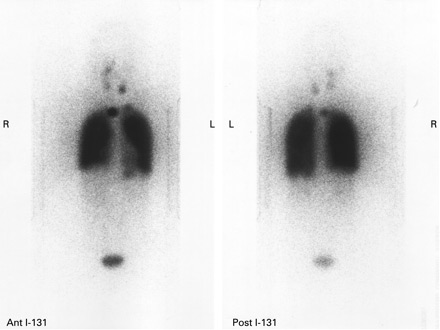

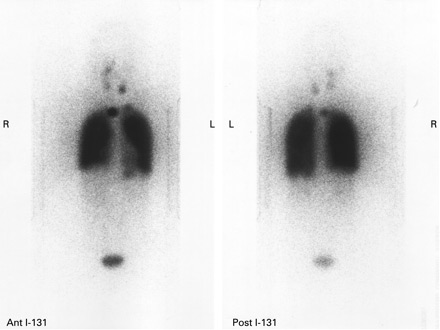

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Increased uptake of radioiodine in both pulmonary fields and the mediastinum due to miliary lung metastasis from papillary thyroid carcinomaGkountouvas A, Chatjimarkou F, Thomas D, et al. Miliary lung metastasis due to papillary thyroid carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0322 [Citation ends].

Differentiated thyroid cancer: recurrence or metastatic disease

The risk of recurrence is determined at time of diagnosis and re-evaluated as a continuum in response to early therapies.[66]Tuttle RM, Alzahrani AS. Risk stratification in differentiated thyroid cancer: from detection to final follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Mar 15;104(9):4087-100.

https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/104/9/4087/5380478

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30874735?tool=bestpractice.com

Serum thyroglobulin assays and neck ultrasound are the mainstays of differentiated thyroid cancer follow-up.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

Recurrence may be biochemical or structural.

Management of patients who develop biochemical recurrence (i.e., rising or newly elevated thyroglobulin levels), without evidence of structural disease, comprises observation and surveillance with appropriate imaging studies performed at time intervals guided by the thyroglobulin doubling time.[83]Scharpf J, Tuttle M, Wong R, et al. Comprehensive management of recurrent thyroid cancer: an American Head and Neck Society consensus statement. Head Neck. 2016 Dec;38(12):1862-9.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hed.24513

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27717219?tool=bestpractice.com

Patients with suspected structural neck recurrence (biopsy-proven persistent or recurrent disease) may require additional therapies or may be managed with observation and serial cross-sectional imaging (e.g., contrast-enhanced computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) at a frequency sufficient to identify clinically significant disease progression.[83]Scharpf J, Tuttle M, Wong R, et al. Comprehensive management of recurrent thyroid cancer: an American Head and Neck Society consensus statement. Head Neck. 2016 Dec;38(12):1862-9.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hed.24513

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27717219?tool=bestpractice.com

Recurrent structural disease that measures 8-10 mm or larger on anatomic imaging in the central and lateral neck, respectively, is considered for revision surgery.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]Scharpf J, Tuttle M, Wong R, et al. Comprehensive management of recurrent thyroid cancer: an American Head and Neck Society consensus statement. Head Neck. 2016 Dec;38(12):1862-9.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hed.24513

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27717219?tool=bestpractice.com

Metastases are observed most frequently in patients with aggressive histologic subtypes, and may occur in up to 10% of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer.[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

[84]Tumino D, Frasca F, Newbold K. Updates on the management of advanced, metastatic, and radioiodine refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017 Nov 20;8:312.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2017.00312/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29209273?tool=bestpractice.com

For the management of metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer, the American Thyroid Association recommends a preferred hierarchy of surgical excision of locoregional disease, radioactive iodine therapy for radioactive iodine-responsive disease (with TSH-suppressive therapy), directed local therapies (e.g., external beam radiation therapy, thermal ablation), and systemic therapy with kinase inhibitors.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

For patients with stable or slowly progressive asymptomatic metastatic disease, TSH-suppressive thyroid hormone therapy alone can be used.[1]Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, et al; American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):1-133.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2015.0020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26462967?tool=bestpractice.com

If distant metastases are radioactive iodine-responsive, radioactive iodine therapy is repeated every 6-12 months depending on rate of growth and response; however, uncertainty exists around the optimal activity and how it should be determined (empiric vs. dosimetric activities), as well as the potential long-term complications.[85]Verburg FA, Hänscheid H, Luster M. Radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy for metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Jun;31(3):279-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28911724?tool=bestpractice.com

As tumors progress, they may lose their ability to concentrate radioactive iodine.[33]Fugazzola L, Elisei R, Fuhrer D, et al. 2019 European Thyroid Association guidelines for the treatment and follow-up of advanced radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. Eur Thyroid J. 2019 Oct;8(5):227-45.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/8/5/ETJ502229.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31768334?tool=bestpractice.com

Radioactive iodine refractoriness occurs in around 60% to 70% of metastatic thyroid cancers, but less than 5% of all patients with thyroid cancer.[33]Fugazzola L, Elisei R, Fuhrer D, et al. 2019 European Thyroid Association guidelines for the treatment and follow-up of advanced radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. Eur Thyroid J. 2019 Oct;8(5):227-45.

https://etj.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/etj/8/5/ETJ502229.xml

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31768334?tool=bestpractice.com

Systemic therapy for recurrent or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer

Treatment with kinase inhibitors, or other targeted therapies, may be considered for patients with progressive differentiated thyroid cancer who are not suitable for or not responsive to local treatment (including surgery and radioactive iodine therapy).

Genetic testing to identify potential actionable mutations/alterations (e.g., NTRK, BRAF, RET, mismatch repair deficiency [dMMR], microsatellite instability [MSI], tumor mutational burden [TMB]) is recommended prior to initiating therapy.[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[72]Shonka DC Jr, Ho A, Chintakuntlawar AV, et al. American Head and Neck Society Endocrine Surgery Section and International Thyroid Oncology Group consensus statement on mutational testing in thyroid cancer: defining advanced thyroid cancer and its targeted treatment. Head Neck. 2022 Jun;44(6):1277-300.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35274388?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl DM, et al. ESMO clinical practice guideline update on the use of systemic therapy in advanced thyroid cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022 Jul;33(7):674-84.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)00694-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35491008?tool=bestpractice.com

If systemic therapy is indicated, the following kinase inhibitors are recommended first-line options:[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Alternative kinase inhibitors that may be considered include:[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Cabozantinib (if progression occurs after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib)

Larotrectinib or entrectinib or repotrectinib (for NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors)

Selpercatinib or pralsetinib (for RET gene fusion-positive tumors).

Targeted therapies that may be considered for patients with unresectable recurrent or metastatic solid tumors that have progressed following prior treatment with no satisfactory alternative treatment options, include:[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Pembrolizumab (a programmed death receptor-1 [PD-1]-blocking monoclonal antibody for patients with TMB-high [≥10 mutations/megabase] tumors, or MSI-high or dMMR tumors)

Dabrafenib plus trametinib (for patients with BRAF V600E mutation).

The optimal sequence of systemic therapy in this setting is unclear. Decision-making should be based on factors including expected treatment response, drug safety profile, and patient preference.

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage (often with distant metastases), displays extremely aggressive behavior, and is associated with a very poor prognosis.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

[74]European Society for Medical Oncology. Clinical practice guidelines - thyroid cancer. 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.esmo.org/guidelines/guidelines-by-topic/endocrine-and-neuroendocrine-cancers/thyroid-cancer

Early multidisciplinary involvement including the palliative care teams is important to support patient decision-making.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

Determining the extent of disease and assessing for mutations influences the treatment options (including eligibility for clinical trials) and goals of care.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

Combining multiple therapeutic modalities (surgery, radiation therapy, systemic therapy [chemotherapy, targeted therapy]) is the most effective approach to treating anaplastic thyroid cancer, but needs to be individualized to optimally balance risks and benefits.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Radioactive iodine therapy is not used because anaplastic tumors do not take up radioiodine.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

Anaplastic thyroid cancer: management approaches

If possible, a total thyroidectomy is done. Determining whether a patient is a candidate for surgery depends on the tumor's resectability, extent of local invasion, need for urgent tracheostomy, presence of distant metastases, and the patient's performance status and treatment goals.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

Thyroid hormone replacement is required post-total thyroidectomy.

Regardless of the surgical status, radiation therapy should be considered early in the treatment of anaplastic thyroid cancer.[86]Rao SN, Smallridge RC. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: an update. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 May 27;101678.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35668021?tool=bestpractice.com

Chemotherapy with paclitaxel, docetaxel, or combined treatments (e.g. carboplatin/paclitaxel, docetaxel/doxorubicin) is associated with very low response rates and significant toxicities. Chemotherapy may, however, be considered:[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

for its radiosensitizing effect when combined with radiation therapy, or

as a bridge to targeted therapy by patients awaiting results of molecular profiling.

Use of targeted therapy in patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer depends on the results of genetic testing.[13]Bible KC, Kebebew E, Brierley J, et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2021 Mar;31(3):337-86.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/thy.2020.0944

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33728999?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma [internet publication].

https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

[46]Filetti S, Durante C, Hartl DM, et al. ESMO clinical practice guideline update on the use of systemic therapy in advanced thyroid cancer. Ann Oncol. 2022 Jul;33(7):674-84.

https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(22)00694-9/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35491008?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Maniakas A, Zafereo M, Cabanillas ME. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: new horizons and challenges. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2022 Jun;51(2):391-401.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35662448?tool=bestpractice.com

[88]Wang JR, Zafereo ME, Dadu R, et al. Complete surgical resection following neoadjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in BRAF(V600E)-mutated anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2019 Aug;29(8):1036-43.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6707029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31319771?tool=bestpractice.com

Dabrafenib plus trametinib: may be considered prior to surgery (to improve resectability) in patients with the BRAF V600E mutation and locoregional disease.

Larotrectinib or entrectinib or repotrectinib: for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors.

Selpercatinib or pralsetinib: for patients with RET gene fusion-positive tumors.

Immunotherapy: for example, pembrolizumab, for patients with TMB-H tumors.