Etiology

Genetic alterations underlie most thyroid cancers.

In differentiated (papillary, follicular) thyroid cancers, BRAF (rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma homolog B) and RAS (rat sarcoma) mutations or RET/PTC (REarranged during Transfection/papillary thyroid cancer) rearrangements are the most common genetic alterations.[26]

Papillary thyroid carcinomas are usually characterized by BRAF mutations (e.g., BRAF V600E substitution) and by RET/PTC rearrangements that activate effector signaling through a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK).[27][28]

Follicular thyroid carcinomas are associated with RAS mutations or have a chromosomal translocation that fuses the paired box gene 8 with the PPAR (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) gamma gene, the PAX8::PPARG fusion oncogene.[27]

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) has a heterogeneous molecular scenario including TP53 (tumor protein P53), TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase), BRAF, and RAS mutations.[28] Other mutations in ATC include: genetic alterations in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway such as mutations in PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) and PI3KCA; genes involved in epigenetic regulation such as SWI/SNF (SWItch/Sucrose Non-Fermentable) chromatin remodeling complex and histone methyltransferases; genes involved in cell-cycle regulation (CDKN2A, CDKN2B, and CCNE1); and genes of tumor immune regulation (PDL1, PDL2, and JAK2).[27][13][28]

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is either sporadic or hereditary (associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia [MEN] syndrome or as an isolated familial form).[4] Almost all cases of hereditary MTC, and approximately 50% cases of sporadic MTC, are associated with mutations in the REarranged during Transfection (RET) proto-oncogene, which codes for a tyrosine kinase receptor expressed in neural crest-derived tissues.[4][29] Sporadic MTC may be associated with RAS mutations in up to 23% of cases.[28]

Primary thyroid lymphoma is linked to chronic stimulation of antigens, as seen in chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (Hashimoto disease) and is postulated to result from the development of intrathyroidal lymphoid tissue.[6] The most common lymphoma subtype is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (more than 50% of cases), followed by mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (between 10% and 23%).[5] See Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and MALT lymphoma.

Pathophysiology

Thyroid cancers derive from thyroid follicular epithelial cells or parafollicular C cells (medullary thyroid cancer).[14]

Follicular cells are heterogeneous, with thyroid follicles having variable growth capability and sensitivity to thyroid-stimulating hormone; if somatic mutations occur, thyrocytes gain different growth potential.[30] Follicular-derived thyroid cancers may be differentiated (papillary, follicular, oncocytic), poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated (anaplastic).[7][8] Oncocytic cells (previously known as Hürthle cells) are thyroid follicular cells with an oncocytic appearance, characterized by hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli and granular eosinophilic cytoplasm.[31]

Mutations that provide a selective growth advantage, thus promoting cancer development, are identified in more than 90% of thyroid cancers.[28] Most thyroid cancers harbor mutations along the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathways.[14][28] Common activating mutations in the MAPK pathway include RET/PTC and NTRK (neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase) rearrangements, and RAS and BRAF mutations.[28]

Physiologic behavior depends on tumor type

Thyroid cancer is thought to reflect a continuum from well differentiated to anaplastic, characterized by early and late genetic events.[32]

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (PDTC) is a follicular neoplasm that shows limited evidence of follicular cell differentiation. It lies morphologically and behaviorally between differentiated (papillary, follicular, oncocytic) and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Differentiated thyroid cancers or PDTCs that lose their ability to take up and concentrate radioiodine (and in some cases to produce thyroglobulin) during tumor progression are commonly termed dedifferentiated thyroid cancers.[33] Up to two-thirds of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer experience tumor dedifferentiation.[34]

Papillary carcinoma tends to spread to local lymph nodes, whereas follicular and oncocytic carcinoma more often spread hematogenously. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is aggressive with a high propensity for local invasion and metastatic spread. Nodal spread is common with primary thyroid lymphomas.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Skull x-ray showing extensive metastases from follicular thyroid carcinomaWani AM, Hussain WM, Fatani MI, et al. Skull metastases from thyroid carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2009; doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2009.1578 [Citation ends].

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is either sporadic (75%) or hereditary (25%).[28] Hereditary MTC can occur as a component of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2A (MEN2A) or MEN2B, or can occur in an isolated familial form.[4] Almost all patients with MEN2A, MEN2B, or isolated familial MTC have germline mutations in the RET proto-oncogene (which codes for a tyrosine kinase receptor expressed in neural crest-derived tissues), and approximately 50% of sporadic MTCs have somatic RET mutations.[4] RAS mutations are present in up to 23% of sporadic MTC cases.[28] In patients with sporadic MTC, the presence of RET mutations is associated with a worse outcome (higher tumoral staging, a higher T category, and the presence of lymph-node and distant metastases); those with RAS mutations had a less aggressive phenotype and a better prognosis.[35]

Classification

Types of thyroid cancer

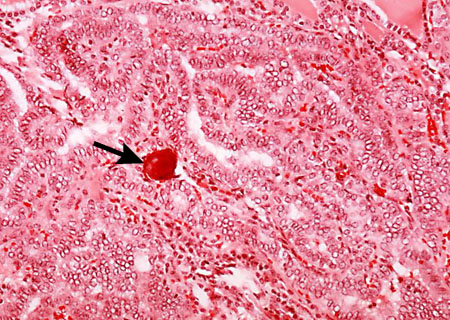

Papillary: the most common type and accounts for 80% of thyroid cancers.[1] It is usually well differentiated with a tendency toward multicentricity and lymph node involvement.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histopathology of papillary carcinoma, thyroid: a psammoma body is visible (arrow)CDC Image Library/Dr Edwin P. Ewing, Jr [Citation ends].

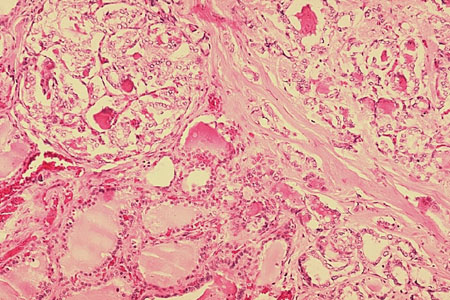

Follicular: accounts for approximately 10% of thyroid cancers.[1] Follicular thyroid carcinomas are malignant follicular tumors with capsular and/or vascular invasion. They spread through direct hematogenous invasion rather than lymph nodes. Early forms are indolent, whereas widely invasive forms are aggressive.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Histopathology of follicular carcinoma, thyroidCDC Image Library/Dr Edwin P. Ewing, Jr [Citation ends].

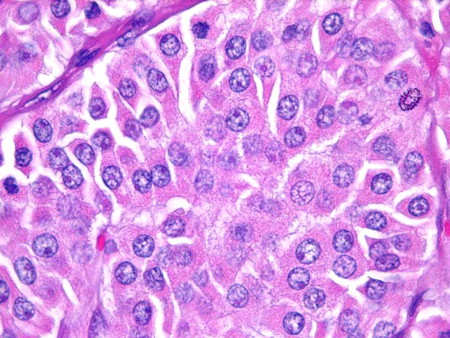

Oncocytic (previously known as Hürthle cell): accounts for 3% to 4% of thyroid cancers.[2] Oncocytic cells have a classic cytologic appearance of large cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasms, and large hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Oncocytic thyroid carcinomas are malignant tumors with capsular and/or vascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, or distant metastasis and are considered to be more aggressive than non-oncocytic follicular thyroid carcinomas.[2]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oncocytic cells (previously known as Hürthle cells) with abundant granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and ‘cherry pink’ nucleoliSandoval MAS et al. Case Reports 2011;2011:bcr1120103536; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oncocytic carcinoma (previously known as Hürthle cell carcinoma): presence of tumor cells within a vein, indicative of vascular invasionSandoval MAS et al. Case Reports 2011;2011:bcr1120103536; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Oncocytic carcinoma (previously known as Hürthle cell carcinoma): presence of tumor cells within a vein, indicative of vascular invasionSandoval MAS et al. Case Reports 2011;2011:bcr1120103536; used with permission [Citation ends].

Anaplastic: an undifferentiated neoplasm with vascular invasion. It usually presents with local encroachment into the recurrent laryngeal nerve and trachea, muscle, and/or esophagus.[3]

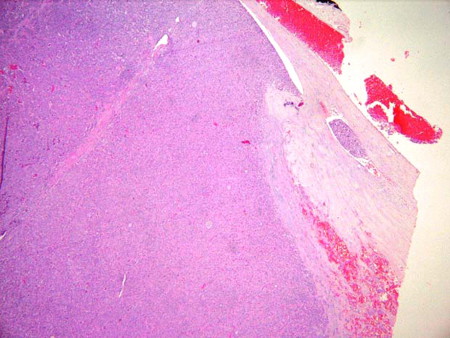

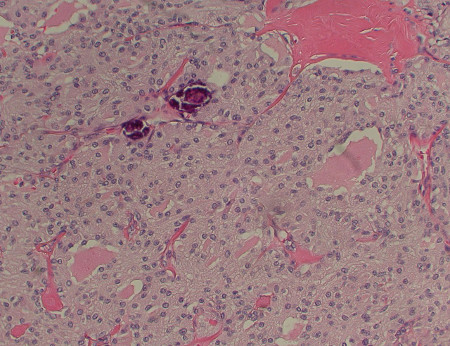

Medullary: originates in thyroid parafollicular C cells and accounts for approximately 1% to 3% of thyroid cancers.[4] It occurs sporadically, or can be hereditary. A minority (approximately one quarter) of cases are hereditary; for example, part of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. There is a tendency to multicentricity and early lymph node spread.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medullary thyroid cancer: H&E stain showing nests of tumor cellsMohan V et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2019;12:e230446; used with permission [Citation ends].

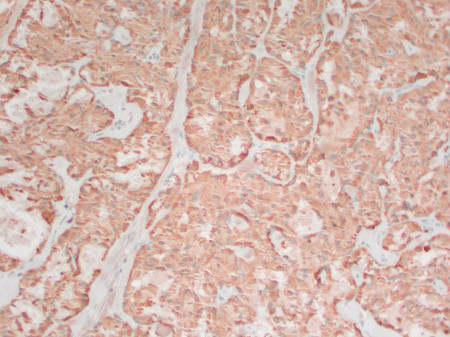

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medullary thyroid cancer: calcitonin stainMohan V et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2019;12:e230446; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Medullary thyroid cancer: calcitonin stainMohan V et al. BMJ Case Reports CP 2019;12:e230446; used with permission [Citation ends].

Lymphoma: generally a B cell-type non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[5] It generally arises in the setting of preexisting Hashimoto thyroiditis.[6] See Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and MALT lymphoma.

2022 World Health Organization (WHO) classification: thyroid tumors[7]

Follicular cell-derived neoplasms

Benign tumors

Follicular nodular disease

Follicular adenoma

Follicular adenoma with papillary architecture

Oncocytic adenoma

Low-risk neoplasms

Noninvasive follicular neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features

Tumors of uncertain malignant potential

Follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential

Well-differentiated tumor of uncertain malignant potential

Hyalinizing trabecular tumor

Malignant neoplasms

Follicular carcinoma

Invasive encapsulated follicular variant papillary carcinoma

Papillary carcinoma

Oncocytic carcinoma

Follicular-derived carcinomas, high-grade

Poorly differentiated carcinoma

Differentiated high-grade carcinoma

Anaplastic follicular cell-derived carcinoma

Thyroid C-cell-derived carcinoma

Medullary thyroid carcinoma

The 2023 Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology[8]

A standardized reporting system with six diagnostic categories for thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA) specimens. Each category has an implied cancer risk that recommends the next clinical management step.

Diagnostic categories based on FNA cytology:

Nondiagnostic

Cyst fluid only

Virtually acellular specimen

Other (obscuring blood, clotting artifact, drying artifact, etc.)

Benign

Consistent with follicular nodular disease (includes adenomatoid nodule, colloid nodule, etc.)

Consistent with chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto) thyroiditis in the proper clinical context

Consistent with granulomatous (subacute) thyroiditis

Other

Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS)

Specify if AUS-nuclear atypia or AUS-other

Follicular neoplasm

Specify if oncocytic (formerly Hürthle cell) type

Suspicious for malignancy

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma

Suspicious for medullary thyroid carcinoma

Suspicious for metastatic carcinoma

Suspicious for lymphoma

Other

Malignant

Papillary thyroid carcinoma

High-grade follicular-derived carcinoma

Medullary thyroid carcinoma

Undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Carcinoma with mixed features (specify)

Metastatic malignancy

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Other

TNM staging of thyroid cancer[9][10]

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM staging classification for differentiated, anaplastic, and medullary thyroid carcinoma is based on the following anatomic factors:

Size and extent of the primary tumor (T)

Regional lymph node involvement (N)

Presence or absence of distant metastases (M)

Staging for differentiated thyroid carcinoma is further categorized by age less than 55 years and 55 years and older.

American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging, Reporting, and Data System (ACR TI-RADS)[11]

A risk stratification system for thyroid nodules based on ultrasound features (composition, echogenicity, shape, margin, echogenic foci, nodule size) to guide decisions regarding fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or follow-up.

Composition (choose 1)

Cystic or almost completely cystic: 0 points

Spongiform: 0 points

Mixed cystic and solid: 1 point

Solid or almost completely solid: 2 points

Echogenicity (choose 1)

Anechoic: 0 points

Hyperechoic or isoechoic: 1 point

Hypoechoic: 2

Very hypoechoic: 3 points

Shape (choose 1)

Wider-than-tall: 0 points

Taller-than-wide: 3 points

Margin (choose 1)

Smooth: 0 points

Ill-defined: 0 points

Lobulated or irregular: 2 points

Extra-thyroidal extension: 3 points

Echogenic foci (choose all that apply)

None or large comet-tail artifacts: 0 points

Macrocalcifications: 1 point

Peripheral (rim) calcifications: 2 points

Punctate echogenic foci: 3 points

The total number of points from all ultrasound features (categories) determine TI-RADS risk stratification (TR1 to TR5)

TR1 (benign): 0 points

TR2 (not suspicious): 2 points

TR3 (mildly suspicious): 3 points

TR4 (moderately suspicious): 4 to 6 points

TR5 (highly suspicious): 7 points or more

Recommendations for FNA or follow-up are based on TI-RADS risk stratification and nodule size

TR1: no FNA

TR2: no FNA

TR3: FNA if nodule is ≥2.5 cm, or follow if ≥1.5 cm

TR4: FNA if nodule is ≥1.5 cm, or follow if ≥1 cm

TR5: FNA if nodule is ≥1 cm, or follow if ≥0.5 cm. FNA of 0.5 to 0.9 cm TR5 nodules may be appropriate for papillary microcarcinomas in certain circumstances

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer