Discogenic back pain is an extremely complex multifactorial problem that poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the clinician. A clear understanding of the pathology, patient expectations, and goals of treatment need to be formulated early on in the process.

Patients who are in the early stages of degenerative disk disease (i.e., with early or no degenerative changes) usually respond well to conservative treatment (analgesia, physical therapy, therapeutic needling options) with a multidisciplinary approach. The majority of patients with acute exacerbations of discogenic back pain will improve by 4 weeks.[99]Vroomen PC, de Krom MC, Knottnerus JA. Predicting the outcome of sciatica at short-term follow-up. Br J Gen Pract. 2002 Feb;52(475):119-23.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1314232/pdf/11887877.pdf

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11887877?tool=bestpractice.com

Approximately 90% of patients will have resolution of symptoms within 3 months of onset, with or without treatment.[4]Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1999 Aug 14;354(9178):581-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10470716?tool=bestpractice.com

Only a small proportion (5%) of people with an acute episode of low back pain (LBP) develop chronic LBP and related disability.[100]Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ. 2006 Jun 17;332(7555):1430-4.

http://www.bmj.com/content/332/7555/1430?view=long&pmid=16777886

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16777886?tool=bestpractice.com

Referral to a surgeon is recommended when nonsurgical modalities have proved to be ineffective. Successful surgical management is greatly dependent on the identification of the surgical pathology and identification of specific pain generators that may be amenable to surgical treatment.

In an event of acute exacerbation of a preexisting chronic back pain, the clinician should seek out the cause of the acute symptoms. It is imperative to exclude other causes of acute symptoms such as diskitis.

Neurological emergency

A presumed diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome (CES) necessitates an urgent referral to the hospital. CES consists of saddle (perineal) anesthesia, sphincteric dysfunction, bladder retention, and leg weakness. Emergency decompression of the spinal canal within 48 hours after the onset of symptoms is required.

A painful nerve root deficit (motor deficit with pain in the same dermatome) in the presence of identifiable disk compression is amenable to surgery. It should be differentiated from a painless nerve deficit (e.g., a painless foot drop) and from a peripheral nerve lesion.

Pharmacological treatments

Topical or oral analgesia may be considered for the pharmacological management of low back pain.

Topical pain relief

Acute symptoms can also be managed with topical analgesia.[101]Jorge LL, Feres CC, Teles VE. Topical preparations for pain relief: efficacy and patient adherence. J Pain Res. 2010 Dec 20;4:11-24.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3048583

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21386951?tool=bestpractice.com

Capsaicin depletes the local resources of substance P, which is implicated in the mediation of noxious stimuli.[102]Anand P, Bley K. Topical capsaicin for pain management: therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action of the new high-concentration capsaicin 8% patch. Br J Anaesth. 2011 Oct;107(4):490-502.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3169333

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21852280?tool=bestpractice.com

Topical NSAIDs are useful in pain that may be mediated through muscular causes.

[  ]

What are the effects of topical NSAIDS in adults with acute musculoskeletal pain?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1129/fullShow me the answer Limited local absorption helps to treat symptoms arising from periarticular structures, and systemic absorption delivers the therapeutic agent to intracapsular structures.[103]Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD007402.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26068955?tool=bestpractice.com

Plasma NSAID concentration following topical administration is typically <5% of that following oral NSAID administration and is, therefore, less effective. However, use of topical NSAIDs can potentially limit systemic adverse events.[103]Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD007402.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26068955?tool=bestpractice.com

]

What are the effects of topical NSAIDS in adults with acute musculoskeletal pain?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1129/fullShow me the answer Limited local absorption helps to treat symptoms arising from periarticular structures, and systemic absorption delivers the therapeutic agent to intracapsular structures.[103]Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD007402.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26068955?tool=bestpractice.com

Plasma NSAID concentration following topical administration is typically <5% of that following oral NSAID administration and is, therefore, less effective. However, use of topical NSAIDs can potentially limit systemic adverse events.[103]Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, et al. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD007402.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007402.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26068955?tool=bestpractice.com

Oral pain relief

Acetaminophen is often used in mild or moderate pain, as it may offer a more favorable safety profile than NSAIDs.[104]Chou R, Huffman LH. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):505-14.

http://www.annals.org/content/147/7/505.full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17909211?tool=bestpractice.com

However, UK guidelines do not recommend acetaminophen alone as a first line agent for managing low back pain.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

Oral NSAIDs are frequently used and are effective for symptomatic relief in patients with acute low back pain.[105]van der Gaag WH, Roelofs PD, Enthoven WT, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Apr 16;4:CD013581.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013581

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32297973?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

What are the effects of topical NSAIDS in adults with acute musculoskeletal pain?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1129/fullShow me the answer No specific NSAID has been found to be more effective than any other.[106]Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD000396.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18253976?tool=bestpractice.com

NSAIDs should only be used for a limited time (no longer than 3 months). Gastric protection, such as a proton-pump inhibitor, should be considered in patients who are on prolonged NSAID therapy, especially if they are at higher risk for having gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., older people).[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

]

What are the effects of topical NSAIDS in adults with acute musculoskeletal pain?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1129/fullShow me the answer No specific NSAID has been found to be more effective than any other.[106]Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD000396.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18253976?tool=bestpractice.com

NSAIDs should only be used for a limited time (no longer than 3 months). Gastric protection, such as a proton-pump inhibitor, should be considered in patients who are on prolonged NSAID therapy, especially if they are at higher risk for having gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., older people).[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

Opioid analgesics may be used judiciously in patients with acute severe, disabling pain that is not controlled (or is unlikely to be controlled) with acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

A weak opioid can also be considered (with or without acetaminophen) for acute low back pain if NSAIDs are contraindicated, or not tolerated.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

Opioid medication should not be used to treat chronic low back pain.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

[107]Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018 Mar 6;319(9):872-82.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2673971

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29509867?tool=bestpractice.com

Muscle relaxants

Muscle relaxants, such as diazepam, are an option for short-term relief of acute low back pain; however, these need to be used with caution because of a risk of adverse effects (primarily sedation) and dependency.[108]van Tulder MW, Touray T, Fulan AD, et al. Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD004252.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004252/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12804507?tool=bestpractice.com

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are used most commonly for chronic low back pain (LBP). Studies have shown that tricyclic antidepressants produced symptom reduction, whereas selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) did not.[109]Staiger TO, Gaster B, Sullivan MD, et al. Systematic review of antidepressants in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003 Nov 15;28(22):2540-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14624092?tool=bestpractice.com

Amitriptyline is useful in improving sleep quality and dealing with the neuropathic element of pain. Due to a lack of evidence, US guidance does not make a recommendation for the use of amitriptyline for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy.[62]Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014 Jan;14(1):180-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239490?tool=bestpractice.com

SSRIs serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, or tricyclic antidepressants are not recommended for management of low back pain in the UK.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

Gabapentin or pregabalin

Some evidence suggests that gabapentin and pregabalin may alleviate pain and improve quality of life in patients with chronic radicular pain, although this is controversial.[110]Yildirim K, Deniz O, Gureser G, et al. Gabapentin monotherapy in patients with chronic radiculopathy: the efficacy and impact on life quality. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2009;22(1):17-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20023359?tool=bestpractice.com

[111]Gilron I. Gabapentin and pregabalin for chronic neuropathic and early postsurgical pain: current evidence and future directions. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007 Oct;20(5):456-72.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17873599?tool=bestpractice.com

[112]Enke O, New HA, New CH, et al. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2018 Jul 3;190(26):E786-93.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6028270

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29970367?tool=bestpractice.com

Pregabalin appears to have better adherence and better bioavailability than gabapentin.

Gabapentinoids or anticonvulsants are not recommended for management of low back pain in the UK.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

Guidance from the US does not make any recommendation for or against the use of gabapentin for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy due to insufficient evidence.[62]Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014 Jan;14(1):180-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239490?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical therapy

Remaining active is recommended for the treatment of acute LBP, rather than bed rest.[113]Hagen KB, Jamtvedt G, Hilde G, et al. The updated Cochrane review of bed rest for low back pain and sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 Mar 1;30(5):542-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15738787?tool=bestpractice.com

[114]Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, et al. Exercise therapy for the treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jul 20;(3):CD000335.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000335.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16034851?tool=bestpractice.com

Education of patients as employed in back schools, regarding positions of ease, exercise, and correct lifting techniques, has shown improved patient outcomes in both the short and intermediate term.[62]Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014 Jan;14(1):180-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239490?tool=bestpractice.com

[115]Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, et al. Back schools for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005 Oct 1;30(19):2153-63.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16205340?tool=bestpractice.com

[116]Heymans MW, de Vet HC, Bongers PM, et al. The effectiveness of high-intensity versus low-intensity back schools in an occupational setting: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006 May 1;31(10):1075-82.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16648740?tool=bestpractice.com

Axial symptoms are likely to be muscular and hence influenced by physical therapy. Therapy with strengthening exercises (both for abdominal wall and for lumbar musculature) has demonstrated positive effects in patients with axial pain.[117]Dickerman RD, Zigler JE. Disocgenic back pain. In: Spivak JM, Connolly PJ, eds. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Spine. 3rd ed. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2006:319-30. However, the timing of exercise is debated, with use of exercise programs being shown to be most effective in subacute (after 2-6 weeks) and chronic disease. A number of exercise regimens have been used. The McKenzie method is a therapist-led system of evaluating and categorizing patients and then prescribing specific exercises.[118]Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. A systematic review of efficacy of McKenzie therapy for spinal pain. Aust J Physiother. 2004;50(4):209-16.

https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0004951414601100/1-s2.0-S0004951414601100-main.pdf?_tid=99aa8043-54c9-4d08-853f-eb39601c6c2d&acdnat=1544532510_9ea0b54ccfd9b965f168a8a6fc2d1314

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15574109?tool=bestpractice.com

The McKenzie method produced better short-term results than nonspecific, generic guidelines and was equal to the results of the strengthening and stabilization protocols.[118]Clare HA, Adams R, Maher CG. A systematic review of efficacy of McKenzie therapy for spinal pain. Aust J Physiother. 2004;50(4):209-16.

https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0004951414601100/1-s2.0-S0004951414601100-main.pdf?_tid=99aa8043-54c9-4d08-853f-eb39601c6c2d&acdnat=1544532510_9ea0b54ccfd9b965f168a8a6fc2d1314

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15574109?tool=bestpractice.com

[119]May S, Donelson R. Evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain with the McKenzie method. Spine J. 2008 Jan-Feb;8(1):134-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18164461?tool=bestpractice.com

Spinal manipulation has been shown to be equivalent to physical therapy in the treatment of acute LBP.[120]Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Battié M, et al. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998 Oct 8;339(15):1021-9.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199810083391502#t=article

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9761803?tool=bestpractice.com

[121]Rubinstein SM, Terwee CB, Assendelft WJ, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep 12;(9):CD008880.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008880.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22972127?tool=bestpractice.com

Use of a variety of interferential systems and stimulators may provide benefit for acute and chronic radicular pain symptoms; however, their use is controversial.[122]Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):492-504.

http://www.annals.org/content/147/7/492.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17909210?tool=bestpractice.com

[123]Hurley DA, McDonough SM, Dempster M, et al. A randomized clinical trial of manipulative therapy and interferential therapy for acute low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 Oct 15;29(20):2207-16.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15480130?tool=bestpractice.com

The use of bracing as either prevention or treatment of LBP has been shown to be ineffective.[124]Jellema P, van Tulder MW, van Poppel MN, et al. Lumbar supports for prevention and treatment of low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2001 Feb 15;26(4):377-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11224885?tool=bestpractice.com

Traction has been used for the treatment of LBP in the past. However, more recent studies have shown no evidence of its value in relation to inactive treatment (bed rest).[125]Luijsterburg PA, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, et al. Physical therapy plus general practitioners' care versus general practitioners' care alone for sciatica: a randomised clinical trial with a 12-month follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2008 Apr;17(4):509-17.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2295266/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18172697?tool=bestpractice.com

[126]Luijsterburg PA, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, et al. Effectiveness of conservative treatments for the lumbosacral radicular syndrome: a systematic review. Eur Spin J. 2007 Jul;16(7):881-99.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2219647/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17415595?tool=bestpractice.com

Alternative therapy

Several therapies may be used within the remits on conventional healthcare systems and as alternative therapies.

The use of nonpharmacologic therapies (e..g, acupuncture, acupressure, and yoga) can be considered.[122]Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):492-504.

http://www.annals.org/content/147/7/492.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17909210?tool=bestpractice.com

[127]Saper RB, Lemaster C, Delitto A, et al. Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: a randomized noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul 18;167(2):85-94.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28631003?tool=bestpractice.com

Therapeutic needling options

Selective nerve root blocks

Inflammation as a cause of radicular symptoms with a mild or moderate compression can be treated by a selective nerve root block.

This is performed with radiological guidance for the placement of a spinal needle in close proximity to the nerve root. A long-acting local anesthetic with or without a local acting corticosteroid is then infiltrated.

Epidural injection

Radicular pain due to multilevel, bilateral pathology can be efficiently treated by an infiltration of long-acting local anesthetic, with or without a local acting corticosteroid.

Evidence suggests that epidural injections (using caudal, transforaminal and lumbar interlaminar routes) improves short- and/or long-term relief of chronic pain secondary to disk herniation and radiculitis.[62]Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014 Jan;14(1):180-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239490?tool=bestpractice.com

[128]Parr AT, Manchikanti L, Hameed H, et al. Caudal epidural injections in the management of chronic low back pain: a systematic appraisal of the literature. Pain Physician. 2012 May-Jun;15(3):E159-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22622911?tool=bestpractice.com

[129]Benyamin RM, Manchikanti L, Parr AT, et al. The effectiveness of lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in managing chronic low back and lower extremity pain. Pain Physician. 2012 Jul-Aug;15(4):E363-404.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22828691?tool=bestpractice.com

[130]Benoist M, Boulu P, Hayem G. Epidural steroid injections in the management of low-back pain with radiculopathy: an update of their efficacy and safety. Eur Spine J. 2012 Feb;21(2):204-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21922288?tool=bestpractice.com

[131]Bicket MC, Horowitz JM, Benzon HT, et al. Epidural injections in prevention of surgery for spinal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Spine J. 2015 Feb 1;15(2):348-62.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25463400?tool=bestpractice.com

[132]Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al. Epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Sep 1;163(5):373-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26302454?tool=bestpractice.com

[133]Manchikanti L, Benyamin RM, Falco FJ, et al. Do epidural injections provide short- and long-term relief for lumbar disc herniation? a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 Jun;473(6):1940-56.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4419020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24515404?tool=bestpractice.com

Reported complications include, rarely, paraplegia related to the foraminal route and associated violation of a radiculomedullary artery.[130]Benoist M, Boulu P, Hayem G. Epidural steroid injections in the management of low-back pain with radiculopathy: an update of their efficacy and safety. Eur Spine J. 2012 Feb;21(2):204-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21922288?tool=bestpractice.com

[134]Spijker-Huiges A, Vermeulen K, Winters JC, et al. Costs and cost-effectiveness of epidural steroids for acute lumbosacral radicular syndrome in general practice: an economic evaluation alongside a pragmatic

randomized control trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 Nov 15;39(24):2007-12.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25202937?tool=bestpractice.com

The evidence for relief of pain secondary to spinal stenosis, axial pain without disk herniation, and post surgery syndrome was also moderate.

One Cochrane review found that epidural corticosteroid injections reduced leg pain and disability for patients with lumbosacral radicular pain.[135]Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, et al. Epidural corticosteroid injections for lumbosacral radicular pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Apr 9;4:CD013577.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013577

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32271952?tool=bestpractice.com

However, treatment effects were small, mainly evident at short‐term follow‐up, and may not be considered clinically important by patients and clinicians.[135]Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Ferreira ML, et al. Epidural corticosteroid injections for lumbosacral radicular pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Apr 9;4:CD013577.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013577

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32271952?tool=bestpractice.com

The American Academy of Neurology assessed the use of epidural corticosteroid injections to treat patients with radicular lumbosacral pain, they suggest that pain may be improved in the short term (2-6 weeks post injection), but no impact on average impairment of function, on need for surgery, or on long-term pain relief beyond 3 months was demonstrated. Routine use is not recommended for patients with radicular lumbosacral pain.[136]Armon C, Argoff CE, Samuels J, et al. Assessment: use of epidural steroid injections to treat radicular lumbosacral pain: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2007 Mar 6;68(10):723-9.

https://www.doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000256734.34238.e7

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17339579?tool=bestpractice.com

Can be injected either in the foramen or in the spinal canal. Infiltration in the spinal canal can be achieved by the lumbar route (through the posterior ligaments), the transforaminal route (through the epidural space targeting a specific nerve root) or the caudal route (through the sacral hiatus).[62]Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014 Jan;14(1):180-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239490?tool=bestpractice.com

Although epidural steroid injections might provide greater benefit than gabapentin for some outcome measures, the differences are modest and are transient in most cases.[137]Cohen SP, Hanling S, Bicket MC, et al. Epidural steroid injections compared with gabapentin for lumbosacral radicular pain: multicenter randomized double blind comparative efficacy study. BMJ. 2015 Apr 16;350:h1748.

http://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h1748.long

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25883095?tool=bestpractice.com

In 2012, an outbreak of fungal infections of the central nervous system was reported in the US in patients who received epidural or paraspinal glucocorticoid injections of preservative-free methylprednisolone acetate prepared by a single compounding pharmacy.[138]Kainer MA, Reagan DR, Nguyen DB, et al; Tennessee Fungal Meningitis Investigation Team. Fungal infections associated with contaminated methylprednisolone in Tennessee. N Engl J Med. 2012 Dec 6;367(23):2194-203.

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1212972

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23131029?tool=bestpractice.com

Although such cases are extremely rare, it highlights the need for the highest standards in drug preparation and injection if these routes of administration are used.

Facet joint blocks

Facetogenic pain is a well-defined clinical entity. The symptoms include axial back pain and posterior thigh pain (typically to the knee). The infiltration of a long-acting local anesthetic agent with or without a local acting corticosteroid can provide an assessment of the origin of the pain from the facet joints.

The infiltration can either be around the medial branch as it crosses over the superomedial aspect of the transverse process, or it could be intra-articular. The former is a more accurate intervention. The facet joints have a dual-level innervation; hence, the level above should be injected as well.

Spinal injections are not recommended for the management of low back pain in the UK or the US.[64]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Dec 2020 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG59

[98]Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009 May 1;34(10):1066-77.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19363457?tool=bestpractice.com

The Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) spinal services report recommend that short-term pain relief injections should be replaced with long-term physical and psychological rehabilitation programmes to help patients cope with back pain.[139]Getting It Right First Time. Spinal surgery report may bring benefits for tens of thousands of back pain patients. Jan 2019 [internet publication].

https://www.gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/spinal-surgery-report

Facet rhizolysis

If axial back pain continues for more than 3 months and the patient had a positive response to a facet block for acute pain, radiofrequency ablation may provide a longer-term effect on facetogenic pain, although its efficacy is unclear.[140]Leggett LE, Soril LJ, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for chronic low back pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. 2014 Sep-Oct;19(5):e146-53.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4197759

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25068973?tool=bestpractice.com

[141]Juch JNS, Maas ET, Ostelo RWJG, et al. Effect of radiofrequency denervation on pain intensity among patients with chronic low back pain: the Mint randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2017 Jul 4;318(1):68-81.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5541325

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28672319?tool=bestpractice.com

Surgical management

Neural decompression

Decompression of the nerve roots and neural structures is an important consideration as a part of surgical intervention in patients with acute and chronic radicular pain.[62]Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J. 2014 Jan;14(1):180-91.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24239490?tool=bestpractice.com

Removal of part of the inferior articular process, under cutting of the inferior process, or removal of all of the degenerate facet joints allows for a better subarticular decompression and the removal of one of the potential pain sources.

An indirect decompression can be achieved by placement of interbody grafts to increase the disk height and open up the foramen.

Spinal fusion

Clinical indications for spinal fusion include: failure of conservative treatment, prolonged chronic pain, disability for more than 1 year, and advanced disk degeneration, as identified on magnetic resonance imaging limited to 1 or 2 disk levels.[142]Andersson GB, Shen FH. Operative management of the degenerative disc: posterior and posterolateral procedures. In: Herkowitz HN, Dvorak J, Bell G, et al, eds. The Lumbar Spine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004;317-23.[143]Sidhu KS, Herkowitz HN. Spinal instrumentation in the management of degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1997 Feb;(335):39-53.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9020205?tool=bestpractice.com

However, due to the multifactorial nature of low back pain and the limited and inconsistent success of spinal fusion, indications for surgery vary between countries and surgeons.[144]Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Dec 1;26(23):2521-32; discussion 2532-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11725230?tool=bestpractice.com

In the presence of a clear pathology with evident instability (spondylolysis, isthmic spondylolisthesis with instability, facetal arthropathy with a degenerative spondylolisthesis), the response to physical therapy may be noted for a shorter period of time (6 months) before consideration given to surgery.

In cases of radiculopathy, the presence of symptoms longer than 6 months has been associated with poorer clinical outcomes.[145]Rihn JA, Hilibrand AS, Radcliff K, et al. Duration of symptoms resulting from lumbar disc herniation: effect on treatment outcomes: analysis of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 Oct 19;93(20):1906-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22012528?tool=bestpractice.com

Similar findings were noted in patients treated for spinal stenosis, with treatment at earlier than 12 months of symptom duration correlating with better clinical outcomes.[146]Radcliff KE, Rihn J, Hilibrand A, et al. Does the duration of symptoms in patients with spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis affect outcomes?: analysis of the Spine Outcomes Research Trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 Dec 1;36(25):2197-210.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21912308?tool=bestpractice.com

One systematic review of surgical techniques for the treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis in athletes showed that 84% of the athletes investigated returned to their sporting activities within 5 to 12 months of surgery.[147]Drazin D, Shirzadi A, Jeswani S, et al. Direct surgical repair of spondylolysis in athletes: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31:E9.

http://thejns.org/doi/full/10.3171/2011.9.FOCUS11180

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22044108?tool=bestpractice.com

A thorough understanding of the patient's problems, expectations, lifestyle, and any possible functional overlays can be performed by way of several validated scoring systems (ODI, Roland Morris, SF 36, Nottingham Health Profile, pain scores, pain diagrams, Zung/MSPQ). A clinical assessment of Wadell signs of inappropriate behavior is a useful tool prior to any surgical consideration.[148]Waddell G, McCulloch JA, Kummel E, et al. Nonorganic physical signs in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1980 Mar-Apr;5(2):117-25.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6446157?tool=bestpractice.com

[149]Main CJ, Waddell G. Behavioral responses to examination. A reappraisal of the interpretation of "nonorganic signs". Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 Nov 1;23(21):2367-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9820920?tool=bestpractice.com

These should be viewed in conjunction with the imaging findings and the presumed pathology causing the symptoms. The ability of the clinician to build in these variables into the decision making for spinal fusion is vital to a good surgical outcome.

The basic goal of spinal fusion is to prevent further segmental motion in a painful lumbar motion segment. Therefore, this procedure is most appropriate for patients with evidence of spinal instability (trauma, tumor, infection, deformity, and intervertebral disk disease). In the presence of degenerative disk disease without significant instability, the application of spinal fusion is based on the perception that preventing any motion across a painful disk or removing the disk altogether and fusing the motion segment will stop the progression of the disease and relieve the pain.[150]Hanley EN Jr, David SM. Lumbar arthrodesis for the treatment of back pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999 May;81(5):716-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10360702?tool=bestpractice.com

[151]Kishen TJ, Diwan AD. Fusion versus disk replacement for degenerative conditions of the lumbar and cervical spine: quid est testimonium? Orthop Clin North Am. 2010 Apr;41(2):167-81.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20399356?tool=bestpractice.com

Spinal fusion most commonly involves the use of graft to bridge the fused segments. The graft is either placed in the posterolateral gutters or between the vertebral bodies after excising the space and preparing the endplates (with or without structural supports). Bone morphogenetic proteins have been used with a view to improving the fusion rate.

Several techniques that have been developed and advocated for achieving fusion in the lumbar spine, including: the posterolateral fusion (with pedicle screws or not), the posterior lumbar interbody fusion, the transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, and the anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Generally, the use of instrumentation has been shown to increase the fusion rates but at the cost of increased complication rates, blood loss, and surgical time.[144]Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001 Dec 1;26(23):2521-32; discussion 2532-4.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11725230?tool=bestpractice.com

[152]Fritzell P, Hägg O, Wessberg P, et al. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Jun 1;27(11):1131-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12045508?tool=bestpractice.com

All fusion techniques reduce pain and disability, with no disadvantage identified to using the less demanding of the surgical techniques.[152]Fritzell P, Hägg O, Wessberg P, et al. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002 Jun 1;27(11):1131-41.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12045508?tool=bestpractice.com

[153]Lee GW, Lee SM, Ahn MW, et al. Comparison of posterolateral lumbar fusion and posterior lumbar interbody fusion for patients younger than 60 years with isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 Nov 15;39(24):E1475-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25202935?tool=bestpractice.com

[154]Liu XY, Qiu GX, Weng XS, et al. What is the optimum fusion technique for adult spondylolisthesis-PLIF or PLF or PLIF plus PLF? A meta-analysis from 17 comparative studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 Oct 15;39(22):1887-98.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25099321?tool=bestpractice.com

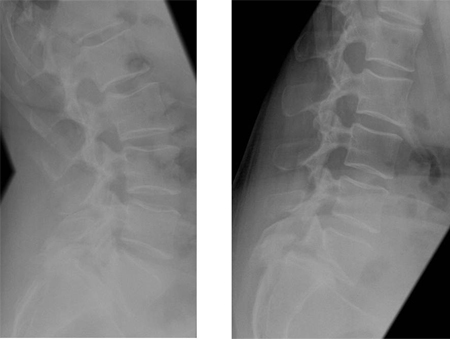

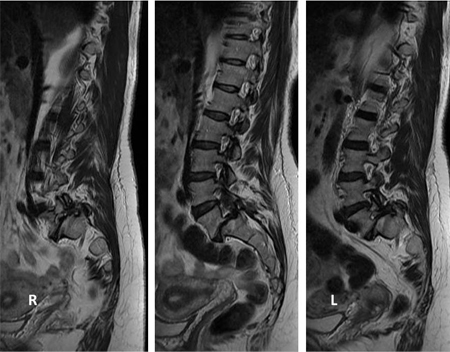

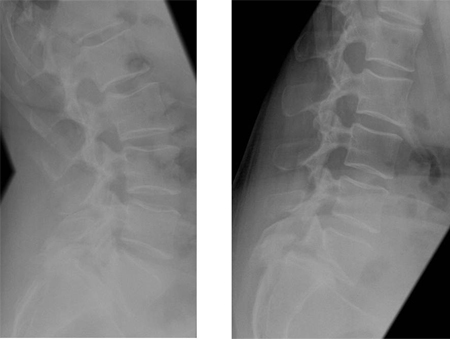

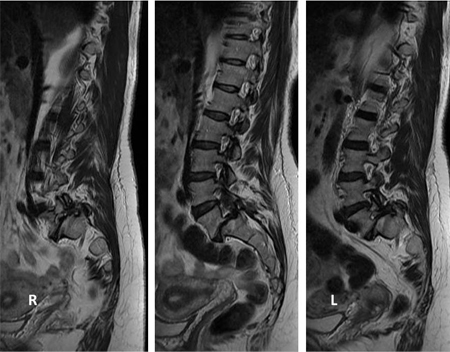

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Spondylolisthesis: flexion/extension viewsFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Preoperative MRI sagittal T2 sequenceFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

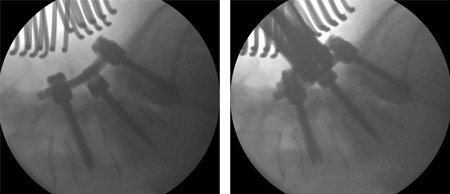

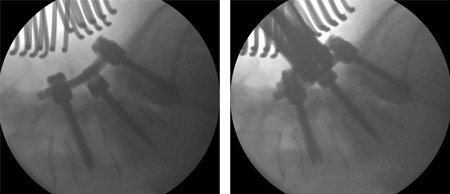

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Preoperative MRI sagittal T2 sequenceFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative images showing a gradual reduction of the deformity: L4 to S1 instrumented fusion, transforaminal fusion at L5S1 and bilateral L5 decompressionFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

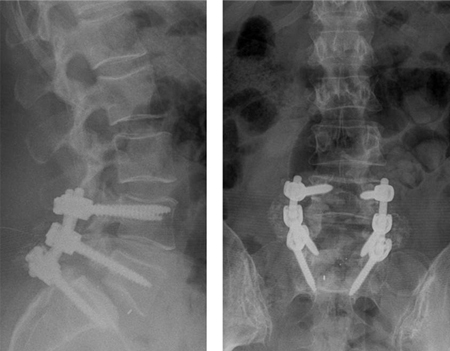

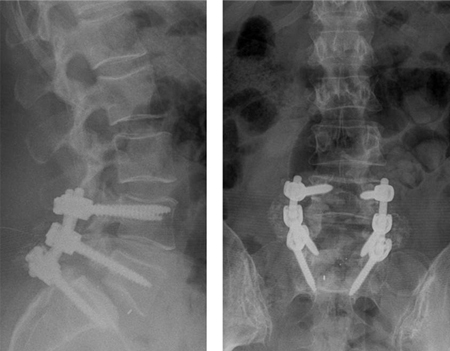

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative images showing a gradual reduction of the deformity: L4 to S1 instrumented fusion, transforaminal fusion at L5S1 and bilateral L5 decompressionFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Postoperative radiographsFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Postoperative radiographsFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pre- and post-surgical views: a patient presents with back pain and neurogenic claudication with stenosis and degenerative slip at L4-5 and a degenerate disk at L5S1 (left, T2-weighted sagittal MRI); L4-S1 decompression and instrumented fusion and a 2-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion was performed (AP radiograph top; lateral, bottom)From the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pre- and post-surgical views: a patient presents with back pain and neurogenic claudication with stenosis and degenerative slip at L4-5 and a degenerate disk at L5S1 (left, T2-weighted sagittal MRI); L4-S1 decompression and instrumented fusion and a 2-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion was performed (AP radiograph top; lateral, bottom)From the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

Artificial disk replacement (ADR)

ADR is another surgical technique, not in routine clinical practice, that involves complete removal of the injured or degenerated disk material and replacement by an artificial disk. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Disk replacement: patient presents with severe back pain, having previously undergone right L5S1 discectomy for a right S1 radiculopathy. Though initially recovered, the right S1 pain recurred after 10 months, with back pain. An MRI scan shows a degenerate L5S1 disk (left, T2-weighted sagittal view). Patient subsequently had a disk replacement (AP radiograph top right, lateral bottom right). The pain in the back and the right leg resolved completelyFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. The aim of this device is to restore the normal kinematics of the disk, relieving pain while avoiding instability and protecting adjacent facets from undue degeneration. The principle of replacing the entire disk is based on the success of other, similar prostheses designed and used for other joints (knee and hip replacements). Therefore, the materials that have been used are also similar (polyethylene, chrome, cobalt, titanium).

The aim of this device is to restore the normal kinematics of the disk, relieving pain while avoiding instability and protecting adjacent facets from undue degeneration. The principle of replacing the entire disk is based on the success of other, similar prostheses designed and used for other joints (knee and hip replacements). Therefore, the materials that have been used are also similar (polyethylene, chrome, cobalt, titanium).

Indications for the use of ADR include: failure of conservative management; and disabling LBP attributed to degenerative disk disease affecting no more than 2 disks.[155]Fekete TF, Porchet F. Overview of disc arthroplasty-past, present and future. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2010 Mar;152(3):393-404.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19844656?tool=bestpractice.com

These indications are similar to those for spinal fusions with some caveats (relatively early involvement of facet joints, lack of gross instability; i.e., spondylolisthesis). Contraindications for the use of ADR include stenosis, facet arthritis, spondylosis or spondylolisthesis, radiculopathy secondary to a herniated disk, sclerosis, osteoporosis, pregnancy, obesity, infection, and fracture.[156]Lin EL, Wang JC. Total disk arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006 Dec;14(13):705-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17148618?tool=bestpractice.com

The efficacy and safety of ADR in comparison with fusion surgery have been thoroughly reported in the literature. Although the initial results were encouraging for the use of ADR, more recent studies with longer follow-up showed that the initial benefit in mobility seemed to be less at 12 months, and at 17 years following surgery, mobility was completely absent, resulting in ankylosis.[157]Zigler JE. Clinical results with ProDisc: European experience and U.S. investigation device exemption study. Spine. 2003 Oct 15;28(20):S163-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14560187?tool=bestpractice.com

[158]Delamarter RB, Fribourg DM, Kanim LE, et al. ProDisc artificial total lumbar disc replacement: introduction and early results from the United States clinical trial. Spine. 2003 Oct 15;28(20):S167-75.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14560188?tool=bestpractice.com

[159]Putzier M, Funk JF, Schneider SV, et al. Charité total disc replacement -clinical and radiographical results after an average follow-up of 17 years. Eur Spine J. 2006 Feb;15(2):183-95.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16254716?tool=bestpractice.com

These findings have generated some caution about the long-term benefits and complications of ADR, especially in terms of preventing ankylosis, and its popularity as a treatment technique has declined.[160]Resnick DK, Watters WC. Lumbar disc arthroplasty: a critical review. Clin Neurosurg. 2007;54:83-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18504901?tool=bestpractice.com

[161]Jacobs WC, van der Gaag NA, Kruyt MC, et al. Total disc replacement for chronic discogenic low back pain: a Cochrane review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 Jan 1;38(1):24-36.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22996268?tool=bestpractice.com

[162]Jacobs W, Van der Gaag NA, Tuschel A, et al. Total disc replacement for chronic back pain in the presence of disc degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep 12;(9):CD008326.

https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008326.pub2/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22972118?tool=bestpractice.com

Multidisciplinary therapy

Trends in the conservative treatment of LBP encourage a multidisciplinary approach.[163]Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001 Jun 23;322(7301):1511-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC33389/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11420271?tool=bestpractice.com

[164]Brox JL, Sorensen R, Karjalainen K, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;26:377-86. The disciplines usually contain a physical element and also a combination of social, occupational, and psychological components. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation was found to be more effective than simple rehabilitation programs.[163]Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001 Jun 23;322(7301):1511-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC33389/?tool=pubmed

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11420271?tool=bestpractice.com

Pain clinic

A multidisciplinary clinic comprising a pain specialist (typically, an anesthetist with a special interest in pain management) with provision of additional input from specialist nurse practitioners, physical therapists, psychologists, and pharmacists.

The goal is to streamline medications, provide input on ergonomic issues, and deal with psychological issues, if any.

The pain physician can undertake procedures such as nerve root and epidural infiltrations and facet rhizolysis.

Functional / vocational rehabilitation

This is defined as whatever helps someone with a health problem to stay at, return to, and remain in work. It is an approach, intervention, and service with a focus toward work-focused health care and accommodating work places to working-age adults. Several return to work programs have been trialed with due attention to manual material handling (MMH) advice and assistive devices, although one Cochrane review found moderate quality evidence that such interventions did not reduce back pain, back pain-related disability, or absence from work when compared with no, or alternative, interventions.[165]Waddell G, Burton AK, Kendall NAS. Vocational rehabilitation: what works, for whom, and when? [internet publication].

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/209474/hwwb-vocational-rehabilitation.pdf

[166]Verbeek J, Martimo KP, Karppinen J, et al. Manual material handling advice and assistive devices for preventing and treating back pain in workers: a Cochrane Systematic Review. Occup Environ Med. 2012 Jan;69(1):79-80.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21849341?tool=bestpractice.com

There was also no evidence from randomized controlled trials to support the effectiveness of MMH advice and training, or MMH assistive devices for the treatment of back pain.

]

Limited local absorption helps to treat symptoms arising from periarticular structures, and systemic absorption delivers the therapeutic agent to intracapsular structures.[103] Plasma NSAID concentration following topical administration is typically <5% of that following oral NSAID administration and is, therefore, less effective. However, use of topical NSAIDs can potentially limit systemic adverse events.[103]

]

Limited local absorption helps to treat symptoms arising from periarticular structures, and systemic absorption delivers the therapeutic agent to intracapsular structures.[103] Plasma NSAID concentration following topical administration is typically <5% of that following oral NSAID administration and is, therefore, less effective. However, use of topical NSAIDs can potentially limit systemic adverse events.[103] ]

No specific NSAID has been found to be more effective than any other.[106] NSAIDs should only be used for a limited time (no longer than 3 months). Gastric protection, such as a proton-pump inhibitor, should be considered in patients who are on prolonged NSAID therapy, especially if they are at higher risk for having gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., older people).[64]

]

No specific NSAID has been found to be more effective than any other.[106] NSAIDs should only be used for a limited time (no longer than 3 months). Gastric protection, such as a proton-pump inhibitor, should be considered in patients who are on prolonged NSAID therapy, especially if they are at higher risk for having gastrointestinal bleeding (e.g., older people).[64] [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Preoperative MRI sagittal T2 sequenceFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Preoperative MRI sagittal T2 sequenceFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative images showing a gradual reduction of the deformity: L4 to S1 instrumented fusion, transforaminal fusion at L5S1 and bilateral L5 decompressionFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Intraoperative images showing a gradual reduction of the deformity: L4 to S1 instrumented fusion, transforaminal fusion at L5S1 and bilateral L5 decompressionFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Postoperative radiographsFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Postoperative radiographsFrom the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pre- and post-surgical views: a patient presents with back pain and neurogenic claudication with stenosis and degenerative slip at L4-5 and a degenerate disk at L5S1 (left, T2-weighted sagittal MRI); L4-S1 decompression and instrumented fusion and a 2-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion was performed (AP radiograph top; lateral, bottom)From the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pre- and post-surgical views: a patient presents with back pain and neurogenic claudication with stenosis and degenerative slip at L4-5 and a degenerate disk at L5S1 (left, T2-weighted sagittal MRI); L4-S1 decompression and instrumented fusion and a 2-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion was performed (AP radiograph top; lateral, bottom)From the collection of Dr N. Quiraishi [Citation ends].

The aim of this device is to restore the normal kinematics of the disk, relieving pain while avoiding instability and protecting adjacent facets from undue degeneration. The principle of replacing the entire disk is based on the success of other, similar prostheses designed and used for other joints (knee and hip replacements). Therefore, the materials that have been used are also similar (polyethylene, chrome, cobalt, titanium).

The aim of this device is to restore the normal kinematics of the disk, relieving pain while avoiding instability and protecting adjacent facets from undue degeneration. The principle of replacing the entire disk is based on the success of other, similar prostheses designed and used for other joints (knee and hip replacements). Therefore, the materials that have been used are also similar (polyethylene, chrome, cobalt, titanium).