Evaluation of a patient with suspected chronic coronary disease (CCD) typically begins with assessment of symptoms and risk factors. Symptoms and risk factors together determine a patient's pretest probability of CCD. Whether calculated formally using risk tables or informally with clinical judgment, pretest probability is the basis for further diagnostic testing.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

An important first step is to ensure that symptoms are stable. Chronic or subacute symptoms that are intermittent and exertional are characteristic of CCD. Acute onset or rapidly progressive chest pain or dyspnea can be signs of acute coronary syndrome or other emergent conditions. Evaluation and risk stratification of these patients is different and usually done in emergency departments or acute care settings. See Evaluation of chest pain.

Clinical history

Angina pectoris - chest discomfort caused by cardiac ischemia - is the cardinal symptom of coronary disease. Patients often describe pressure, tightness, heaviness, or squeezing discomfort rather than "pain". Angina is classically substernal although it may radiate to the neck, jaw, epigastrium, and left or possibly right arm. It is unusual to present above the mandible, below the umbilicus, or localized to a small area of the chest wall. Pain that is sharp, positional, or pleuritic is less characteristic. Anginal symptoms are usually gradual in onset and last minutes rather than being fleeting or prolonged for hours.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Angina is defined by three features:

Substernal chest discomfort of characteristic quality and duration

Provoked by exercise or emotional stress

Relieved with rest or nitroglycerin.

Patients with more of these features are at greater likelihood of having CCD.[65]Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jun 14;300(24):1350-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/440357?tool=bestpractice.com

[66]Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, et al. A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation, updating, and extension. Eur Heart J. 2011 Jun;32(11):1316-30.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/32/11/1316/2398002

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21367834?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Juarez-Orozco LE, Saraste A, Capodanno D, et al. Impact of a decreasing pre-test probability on the performance of diagnostic tests for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Nov 1;20(11):1198-207.

https://academic.oup.com/ehjcimaging/article/20/11/1198/5456837

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30982851?tool=bestpractice.com

However, patients with CCD may have different or additional symptoms including anginal "equivalents", such as dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, numbness, indigestion, and light-headedness.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

In the US there is evidence that women and Black, Hispanic, and South Asian patients are less likely to receive appropriate diagnostic testing for coronary disease. Although women often experience typical symptoms, they are also more likely to experience dyspnea, nausea, and fatigue.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Chest pain has traditionally been described as "typical" if it has all three features of angina, "atypical" if it has two, and "nonanginal" if it has one or none of the features of angina. Some guidelines avoid the term “atypical” and instead suggest "cardiac", "possibly cardiac", and "noncardiac" pain, although symptoms alone can not determine the cause of chest pain.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[68]Anderson HVS, Masri SC, Abdallah MS, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for chest pain and acute myocardial infarction: A report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Data Standards. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022 Oct;15(10):e000112.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000112?rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed&url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36041014?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical examination

The physical examination is often normal or nonspecific in patients with stable angina but may reveal signs of associated conditions such as heart failure (HF), valvular disease, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Findings suggestive of noncoronary atherosclerotic disease, such as diminished pedal pulses, pulsatile abdominal mass, or carotid bruit, increase the likelihood of coronary disease.[65]Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979 Jun 14;300(24):1350-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/440357?tool=bestpractice.com

[69]Chun AA, McGee SR. Bedside diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2004 Sep 1;117(5):334-43.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15336583?tool=bestpractice.com

Presence of a rub suggests pericardial or pleural disease as the source of pain. Pain that is reproduced by palpation of the chest reduces the likelihood of angina.[70]Levine HJ. Difficult problems in the diagnosis of chest pain. Am Heart J. 1980 Jul;100(1):108-18.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6770665?tool=bestpractice.com

Fundoscopy may demonstrate presence of increased light reflexes and arteriovenous nicking, providing evidence of hypertension and associated risk of coronary disease. Elevated blood pressure, xanthomas, and retinopathy suggest the presence of risk factors.

Initial basic testing

As part of initial workup for patients with suspected CCD, basic tests include general biochemical tests, ECG, and imaging in some cases.

Laboratory testing:

Blood tests should include: complete blood count, including hemoglobin to assess for anemia; chemistries with estimation of renal function; lipid panel; screen for diabetes mellitus (fasting blood glucose or HbA1c)

Testing of thyroid function may be included when thyroid disease is considered a possible contributor to angina.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

Resting ECG:

ECG is recommended for all patients without an obvious noncardiac cause of chest pain.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

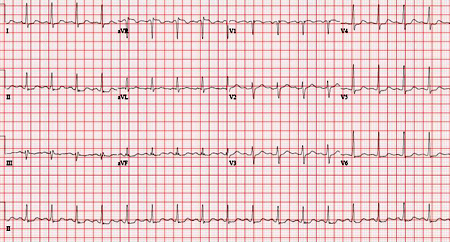

It will be normal in >50% of patients, but may reveal abnormalities such as arrhythmias, Q waves, or ST changes that may increase the likelihood of ischemic heart disease. Furthermore, it can determine baseline abnormalities that may preclude use of exercise ECG for noninvasive stress testing. These include complete left bundle branch block, >1 mm of ST depression, and paced rhythm or preexcitation syndrome. An ECG taken during an episode of chest pain may demonstrate ST-segment depression suggestive of ischemia.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[71]Multimodality Writing Group for Chronic Coronary Disease, Winchester DE, Maron DJ, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE/ASNC/ASPC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2023 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of chronic coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Jun 27;81(25):2445-67.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109723052233?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37245131?tool=bestpractice.com

ECG may reveal comorbid atrial fibrillation.

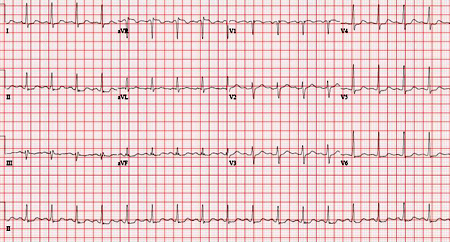

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: ECG showing nonspecific ST depressions in V5 and V6, which may indicate ischemia. There are nonspecific ST-segment changes in III and aVFFrom the collection of Dr S.D. Fihn; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal ECGFrom the collection of Dr S.D. Fihn; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal ECGFrom the collection of Dr S.D. Fihn; used with permission [Citation ends].

Resting echocardiography:

European guidelines endorse echocardiography in all cases of suspected CCD.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

It can be used to identify prior myocardial infarction (MI); suggest alternative causes of chest symptoms; aid in diagnosis of comorbid conditions, such as heart failure, and provide prognostic information in patients with CCD.

However, the value of this additional testing is not well established in patients without history, exam, or ECG findings suggestive of a prior event (e.g., MI, transient ischemic attack) or associated conditions (e.g., HF).

Chest x-ray:

Estimating pretest probability

When the clinical evaluation is complete, the practitioner must determine whether the probability of ischemia warrants further testing.

Pretest probability has typically been estimated from age, sex, and the clinical classification of chest pain: typical (cardiac), atypical (possibly cardiac), or noncardiac.[72]Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB, et al. Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Jan 15;118(2):81-90.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8416322?tool=bestpractice.com

[73]Weiner DA, Ryan TJ, McCabe CH, et al. Exercise stress testing. Correlations among history of angina, ST-segment response and prevalence of coronary-artery disease in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS). N Engl J Med. 1979 Aug 2;301(5):230-5.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/449990?tool=bestpractice.com

Updated pretest probabilities using contemporary data sets also include estimates for patients presenting with dyspnea rather than angina.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[67]Juarez-Orozco LE, Saraste A, Capodanno D, et al. Impact of a decreasing pre-test probability on the performance of diagnostic tests for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Nov 1;20(11):1198-207.

https://academic.oup.com/ehjcimaging/article/20/11/1198/5456837

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30982851?tool=bestpractice.com

These updated data sets suggest lower rates of CCD for most groups. It is not known whether the lower pretest probabilities in contemporary studies are due to changes in population-level prevention efforts (e.g., statins), patient reporting, or study design. The US and European guidelines suggest use of the new, lower pretest probabilities.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Guidelines also suggest adjusting the calculated pretest probability for additional factors (e.g., family history, smoking) as well as other data that may be available (e.g., resting ECG changes, coronary calcium score [CAC]).[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

However, there is no algorithmic way to make such adjustments. There is interest in using CAC testing as an initial screen which might obviate further testing for patients with a CAC score of zero although this strategy has not been endorsed in prominent guidelines.[74]Agha AM, Pacor J, Grandhi GR, et al. The prognostic value of CAC zero among individuals presenting with chest pain: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Oct;15(10):1745-57.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1936878X22002443?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36202453?tool=bestpractice.com

Plasma biomarkers of inflammation and thrombosis have been proposed in the risk stratification of patients with coronary disease. There is insufficient evidence to support routine use of most biomarkers in risk stratification, although some guidelines recommend selected use of c-reactive protein.[33]Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 7;42(34):3227-37.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/34/3227/6358713

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34458905?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Jun 18;139(25):e1082-143.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30586774?tool=bestpractice.com

[75]US Preventive Services Task Force., Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Risk assessment for cardiovascular disease with nontraditional risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018 Jul 17;320(3):272-80.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2687225

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29998297?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pretest probabilities of obstructive coronary artery disease in symptomatic patients according to age, sex, and nature of symptoms in pooled analysisJuarez-Orozco et al. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Nov 1;20(11):1198-207; used with permission [Citation ends]. Note: typical angina indicates presence of all three features of angina (substernal chest pain/discomfort; provoked by exercise or emotional stress; relieved with rest or nitroglycerin); atypical angina indicates presence of two of the three features; nonanginal pain indicates presence of one or none of the features.

Note: typical angina indicates presence of all three features of angina (substernal chest pain/discomfort; provoked by exercise or emotional stress; relieved with rest or nitroglycerin); atypical angina indicates presence of two of the three features; nonanginal pain indicates presence of one or none of the features.

The US and European guidelines recommend diagnostic testing for stable patients with a pretest probability of 15% or higher.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

In patients at lower risk, testing may be deferred, although European guidelines consider testing reasonable for patients with a pretest probability of 5 to 15% and US guidelines consider select testing (CAC score or exercise ECG) reasonable for patients at lower risk. At very low pretest probability, providers should keep in mind that a positive result is more likely to be a false positive (low positive predictive value).

Diagnostic testing

Tests for CCD generally can be divided into two main types: anatomic and functional. Anatomic tests identify atherosclerosis and/or luminal narrowing in epicardial coronary arteries. Functional tests assess myocardial function and/or perfusion at rest and during stress.

Traditionally, the only anatomic test was invasive coronary angiography and the only functional test was noninvasive stress testing. Therefore, functional tests were usually the initial choice for stable disease. Anatomic testing was usually second line and considered the reference standard. However, advances in cardiac imaging now allow for noninvasive anatomic testing. In addition, new procedures in the catheterization lab can now provide functional information as part of an invasive assessment.

These developments have prompted questions about the relative importance of total atherosclerotic burden, focal luminal narrowing, and impaired function in CCD. Emerging research now directly compares the ability of anatomic and functional testing to predict cardiac events and improve clinical outcomes.[76]Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al; PROMISE Investigators. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 2;372(14):1291-300.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1415516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25773919?tool=bestpractice.com

[77]Skelly AC, Hashimoto R, Buckley DI, et al. Noninvasive testing for coronary artery disease. Comparative effectiveness reviews, no. 171. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016:1-363.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0087137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27148617?tool=bestpractice.com

[78]SCOT-HEART Investigators. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 13;385(9985):2383-91.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60291-4/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25788230?tool=bestpractice.com

[79]McKavanagh P, Lusk L, Ball PA, et al. A comparison of cardiac computerized tomography and exercise stress electrocardiogram test for the investigation of stable chest pain: the clinical results of the CAPP randomized prospective trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015 Apr;16(4):441-8.

https://academic.oup.com/ehjcimaging/article/16/4/441/2397463

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25473041?tool=bestpractice.com

[80]Min JK, Koduru S, Dunning AM, et al. Coronary CT angiography versus myocardial perfusion imaging for near-term quality of life, cost and radiation exposure: a prospective multicenter randomized pilot trial. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012 Jul-Aug;6(4):274-83.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22732201?tool=bestpractice.com

[81]Zito A, Galli M, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Diagnostic strategies for the assessment of suspected stable coronary artery disease : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2023 Jun;176(6):817-26.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37276592?tool=bestpractice.com

Noninvasive tests

Stress tests:

Noninvasive functional tests, also called stress tests, remain a key diagnostic modality. Stress tests can be further categorized by the type of stress and the outcome used to assess cardiac function/perfusion.

Exercise is generally preferred as a means of stress because it can provide higher levels of physiologic stress as well as prognostically valuable information about patients' functional status. Use of pharmacologic stress rather than exercise is typically reserved for patients unable to perform moderate exercise due to orthopedic, pulmonary, or other comorbidities. Options for pharmacologic stress testing include vasodilators (adenosine, dipyridamole, or regadenoson) or a beta-agonist (dobutamine).

The outcome measures for stress testing include ECG alone or ECG plus imaging. The most common imaging options are echocardiography and nuclear imaging (SPECT). Positron-emission tomography (PET) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) may also be available. The use of imaging as an outcome for stress testing is required when baseline ECG findings preclude identification of inducible ischemia (such as left bundle-branch block, ventricular pacing, or baseline ST-segment depressions ≥0.5 mm). Imaging is also usually required when a pharmacologic stress is used. The addition of imaging to ECG stress testing provides more precise anatomic localization as well as information about the magnitude of inducible ischemia and irreversibly infarcted tissue. Once the decision is made to add imaging, choice of modality depends on the indication for the test (diagnosis, risk stratification, assessment of myocardial viability), and patient-related factors (obesity, concerns about radiation), as well as local expertise and availability. If a patient has undergone one type of testing in the past, repeating the same test can facilitate comparison.

Exercise ECG may have a lower sensitivity in women, although it is not clear this difference should alter diagnostic strategy.[82]Okin PM, Kligfield P. Gender-specific criteria and performance of the exercise electrocardiogram. Circulation. 1995 Sep 1;92(5):1209-16.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.92.5.1209

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7648667?tool=bestpractice.com

[83]Shaw LJ, Mieres JH, Hendel RH, et al; WOMEN Trial Investigators. Comparative effectiveness of exercise electrocardiography with or without myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography in women with suspected coronary artery disease: results from the What Is the Optimal Method for Ischemia Evaluation in Women (WOMEN) trial. Circulation. 2011 Sep 13;124(11):1239-49.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029660

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21844080?tool=bestpractice.com

In addition to predicting the likelihood of obstructive lesions on angiogram, functional testing can stratify patients in relation to risk of cardiovascular mortality. The Duke treadmill score is a well-validated model derived from the duration of exercise, ST-segment changes, and angina on a standard treadmill exercise ECG.[84]Shaw LJ, Peterson ED, Shaw LK, et al. Use of a prognostic treadmill score in identifying diagnostic coronary disease subgroups. Circulation. 1998 Oct 20;98(16):1622-30.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9778327?tool=bestpractice.com

Models with additional variables may improve the ability to identify patients at low risk.[85]Lauer MS, Pothier CE, Magid DJ, et al. An externally validated model for predicting long-term survival after exercise treadmill testing in patients with suspected coronary artery disease and a normal electrocardiogram. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Dec 18;147(12):821-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18087052?tool=bestpractice.com

The addition of imaging to stress ECG can also add prognostic information.[86]Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, et al. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation. 1996 Mar 1;93(5):905-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8598081?tool=bestpractice.com

[87]Marwick TH, Case C, Vasey C, et al. Prediction of mortality by exercise echocardiography: a strategy for combination with the Duke treadmill score. Circulation. 2001 May 29;103(21):2566-71.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11382725?tool=bestpractice.com

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA):

CCTA, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study, can identify coronary plaque and stenosis. CCTA has advanced to achieve high concordance with invasive angiography in identifying significant stenoses and thus offers a noninvasive anatomic test. CCTA can also identify lesser, nonobstructive atherosclerotic lesions (as does invasive angiography). As even these nonobstructive plaques are associated with increased cardiac risk, CCTA can add some predictive power beyond functional testing.[88]Hoffmann U, Ferencik M, Udelson JE, et al; PROMISE Investigators. Prognostic value of noninvasive cardiovascular testing in patients with stable chest pain: insights from the PROMISE trial (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain). Circulation. 2017 Jun 13;135(24):2320-32.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024360

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28389572?tool=bestpractice.com

In particular, the absence of any atherosclerosis on CCTA is associated with very low rates of cardiovascular events for at least 5 years.[89]Xie JX, Cury RC, Leipsic J, et al. The Coronary Artery Disease-Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS): prognostic and clinical implications associated with standardized coronary computed tomography angiography reporting. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Jan;11(1):78-89.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29301713?tool=bestpractice.com

[90]Andreini D, Pontone G, Mushtaq S, et al. A long-term prognostic value of coronary CT angiography in suspected coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012 Jul;5(7):690-701.

http://imaging.onlinejacc.org/content/5/7/690

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22789937?tool=bestpractice.com

Choosing a noninvasive test modality

Comparing tests for CCD is complicated by verification bias, a paucity of head-to-head trials, and uncertainty about the optimal reference standard.[91]Froelicher VF, Lehmann KG, Thomas R, et al. The electrocardiographic exercise test in a population with reduced workup bias: diagnostic performance, computerized interpretation, and multivariable prediction. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study in Health Services #016 (QUEXTA) Study Group. Quantitative exercise testing and angiography. Ann Intern Med. 1998 Jun 15;128(12 pt 1):965-74.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9625682?tool=bestpractice.com

That said, it is useful to roughly compare the ability of noninvasive tests to predict significant stenosis on invasive angiography.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sensitivity and specificity of tests for anatomically significant coronary artery diseaseAdapted from Knuuti et al. The performance of non-invasive tests to rule-in and rule-out significant coronary artery stenosis in patients with stable angina: a meta-analysis focused on post-test disease probability. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 14;39(35):3322-30; used with permission. (CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CI, confidence interval; CMR, stress cardiac magnetic resonance; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography [exercise stress SPECT with or without dipyridamole or adenosine]; Stress echo, exercise stress echocardiography) [Citation ends].

For initial diagnosis, current US and European guidelines recommend either CCTA or stress testing with imaging. Exercise ECG has a limited role.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

UK guidelines emphasize CCTA as the initial diagnostic test for CCD and advise against exercise ECG.[92]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Recent-onset chest pain of suspected cardiac origin: assessment and diagnosis. Nov 2016 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg95

[93]Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of stable angina: a national clinical guideline. Apr 2018 [internet publication].

https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-151-stable-angina

Use of CCTA as an initial diagnostic test is likely to identify patients with subclinical atherosclerosis that would not be identified on functional testing. The risks and benefits of this approach have not been fully defined. A major US trial randomizing patients to functional testing versus CCTA showed an increased rate of invasive catheterization in the CCTA group but no difference in clinical outcomes.[76]Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al; PROMISE Investigators. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 2;372(14):1291-300.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1415516

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25773919?tool=bestpractice.com

A Scottish randomized trial adding CCTA to routine care (including exercise ECG for most patients) showed increased rates of preventative and symptomatic CCD treatments with no difference in overall rates of angiography or revascularization at 5 years.[94]SCOT-HEART Investigators., Newby DE, Adamson PD, et al. Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 6;379(10):924-33.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1805971

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30145934?tool=bestpractice.com

There may be advantages to using CCTA for younger, lower-intermediate risk patients and stress testing for older, higher-risk patients. However, local expertise, availability, as well as patient specific factors may weigh heavily in the choice between CCTA and stress testing with imaging.

Invasive tests

Coronary angiography:

Coronary angiography uses catheters to inject contrast directly into epicardial coronary arteries, providing visualization of the artery lumen and degree of stenosis.

Risks of invasive angiography include those from contrast and radiation, thrombosis or hemorrhage related to vascular access, arrhythmia, and atheroembolism.

Traditionally, lesions causing stenosis greater than 50% to 70% are considered significant, although the presence of lesser degrees of stenosis are also associated with worse cardiac outcomes.[95]Maddox TM, Stanislawski MA, Grunwald GK, et al. Nonobstructive coronary artery disease and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014 Nov 5;312(17):1754-63.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1920971

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25369489?tool=bestpractice.com

Because of the variability in length and irregularity of plaques, estimates of the degree of stenosis may be imperfect, and measurements of luminal narrowing do not necessarily correlate with the level of symptomatic or functional impairment.[96]Tonino PA, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study: fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Jun 22;55(25):2816-21.

http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/55/25/2816

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20579537?tool=bestpractice.com

One of several techniques to overcome the limits of conventional angiography, fractional flow reserve (FFR) is increasingly used to guide decisions about procedural intervention. FFR - the direct measurement of pressure gradients across a stenosis after administration of adenosine - provides functional information about blood flow with a pharmacologic stress. It correlates with stress testing in small studies and predicts the likelihood of future cardiac events.[97]Pijls NH, De Bruyne B, Peels K, et al. Measurement of fractional flow reserve to assess the functional severity of coronary-artery stenoses. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jun 27;334(26):1703-8.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJM199606273342604

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8637515?tool=bestpractice.com

[98]Barbato E, Toth GG, Johnson NP, et al. A prospective natural history study of coronary atherosclerosis using fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Nov 29;68(21):2247-55.

http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/68/21/2247

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27884241?tool=bestpractice.com

Emerging tests

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring:

CAC scoring can identify the overall burden of calcified atherosclerosis without characterizing the severity of specific stenoses.

Guidelines endorse a limited role for CAC testing in risk stratification for asymptomatic patients considering interventions for primary prevention of coronary disease. It can be used, for example, in combination with clinical markers in deciding whether to initiate a statin for primary prevention.[44]Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Jun 18;139(25):e1082-143.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30586774?tool=bestpractice.com

[99]Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 1;41(1):111-88.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/1/111/5556353

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504418?tool=bestpractice.com

There are currently no trials evaluating the use of CAC testing to intensify or de-escalate primary prevention. Guidelines also suggest CAC testing can be considered for risk stratification of stable patients with symptoms and low pretest probability of disease such that no other diagnostic testing would be indicated.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[100]Winther S, Schmidt SE, Mayrhofer T, et al. Incorporating coronary calcification into pre-test assessment of the likelihood of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 24;76(21):2421-32.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109720373678?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33213720?tool=bestpractice.com

For symptomatic patients, an existing CAC score may be incorporated into calculation of a pretest probability to determine whether further diagnostic testing is indicated.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[100]Winther S, Schmidt SE, Mayrhofer T, et al. Incorporating coronary calcification into pre-test assessment of the likelihood of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 24;76(21):2421-32.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109720373678?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33213720?tool=bestpractice.com

Some have proposed using CAC testing as an initial screen for symptomatic patients being evaluated for CCD. The suggestion is that a CAC score of zero might obviate further testing.[74]Agha AM, Pacor J, Grandhi GR, et al. The prognostic value of CAC zero among individuals presenting with chest pain: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022 Oct;15(10):1745-57.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1936878X22002443?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36202453?tool=bestpractice.com

However, this strategy has not been endorsed in prominent guidelines. Not all atheromatous plaques are calcified, and especially in younger, symptomatic patients a negative CAC score may not effectively rule out CCD.[101]Villines TC, Hulten EA, Shaw LJ, et al; CONFIRM Registry Investigators. Prevalence and severity of coronary artery disease and adverse events among symptomatic patients with coronary artery calcification scores of zero undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography: results from the CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Dec 6;58(24):2533-40.

http://www.onlinejacc.org/content/58/24/2533

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22079127?tool=bestpractice.com

[102]Wieske V, Walther M, Dubourg B, et al. Computed tomography angiography versus Agatston score for diagnosis of coronary artery disease in patients with stable chest pain: individual patient data meta-analysis of the international COME-CCT Consortium. Eur Radiol. 2022 Aug;32(8):5233-45.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00330-022-08619-4

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35267094?tool=bestpractice.com

Avoid obtaining a CAC score in patients with known atherosclerotic disease as it offers little additional prognostic value for patients with known disease.[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

[103]Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2021 [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20221003082824/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/society-of-cardiovascular-computed-tomography

[104]Orringer CE, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, et al. The National Lipid Association scientific statement on coronary artery calcium scoring to guide preventive strategies for ASCVD risk reduction. J Clin Lipidol. 2021 Jan-Feb;15(1):33-60.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33419719?tool=bestpractice.com

[105]American College of Cardiology. Five things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely, an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Feb 2023. [internet publication].

https://web.archive.org/web/20230402075927/https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-college-of-cardiology

CT myocardial perfusion (CTP) and fractional flow reserve CT (FFRCT):

Emerging CT technologies aim to add functional information to the anatomic data provided by CCTA. CTP and FFRCT both appear to increase specificity of CCTA with a small loss of sensitivity, although variations in test protocol produce slightly different results.[106]Hamon M, Geindreau D, Guittet L, et al. Additional diagnostic value of new CT imaging techniques for the functional assessment of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2019 Jun;29(6):3044-61.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30617482?tool=bestpractice.com

[107]Celeng C, Leiner T, Maurovich-Horvat P, et al. Anatomical and functional computed tomography for diagnosing hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Jul;12(7 pt 2):1316-25.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1936878X18306818?via%3Dihub

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30219398?tool=bestpractice.com

[108]Patel AR, Bamberg F, Branch K, et al. Society of cardiovascular computed tomography expert consensus document on myocardial computed tomography perfusion imaging. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020 Jan - Feb;14(1):87-100.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32122795?tool=bestpractice.com

Tests for vasospasm and microcirculatory dysfunction:

Some patients have symptoms consistent with angina but lack the classic stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries. For these patients, invasive and noninvasive testing for vasospasm and microcirculatory dysfunction can be considered.[23]Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020 Jan 14;41(3):407-77.

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31504439?tool=bestpractice.com

[24]Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-454.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001029

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34709879?tool=bestpractice.com

Limited evidence shows improved symptoms with tailored therapy.[25]Ford TJ, Stanley B, Good R, et al. Stratified medical therapy using invasive coronary function testing in angina: the CorMicA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 11;72(23 pt a):2841-55.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109718383815

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30266608?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal ECGFrom the collection of Dr S.D. Fihn; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Normal ECGFrom the collection of Dr S.D. Fihn; used with permission [Citation ends].

Note: typical angina indicates presence of all three features of angina (substernal chest pain/discomfort; provoked by exercise or emotional stress; relieved with rest or nitroglycerin); atypical angina indicates presence of two of the three features; nonanginal pain indicates presence of one or none of the features.

Note: typical angina indicates presence of all three features of angina (substernal chest pain/discomfort; provoked by exercise or emotional stress; relieved with rest or nitroglycerin); atypical angina indicates presence of two of the three features; nonanginal pain indicates presence of one or none of the features.