Approach

The vast majority of otherwise healthy patients presenting with a dental infection can be managed on an outpatient basis; however, a major consideration for all odontogenic (tooth-related) infections is the potential for upper airway obstruction due to extension of the infection into the fascial spaces in the oropharynx.

The initial assessment of patients with a suspected dental abscess or odontogenic infection is no different from other dental patients, except there is a need to be highly vigilant for signs of airway compromise.

The history can provide invaluable clues to the diagnosis and guide the evaluation to discover the source and severity of the infection. Dental pain/toothache is the most common presenting symptom. Laboratory studies and imaging should only be obtained after a thorough history and physical examination and, in the case of impending airway compromise, should not delay securing the airway or emergent operative intervention.

Severe odontogenic infections can be potentially life-threatening and require prompt medical and surgical management with early recognition and involvement of an oral and maxillofacial surgeon/head and neck specialist for definitive surgical intervention.

History

The specific history depends on the type of abscess present.

Periapical abscess:

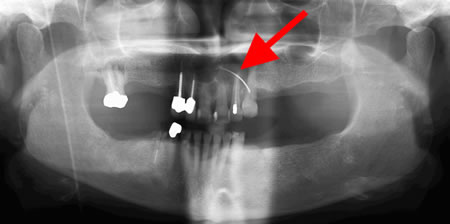

Most patients have a history of poor or limited prior dental care, dental caries, tooth fractures, dental trauma, failed restorations, bruxism, draining fistulae, mobility, extrusion, or prior unsuccessful root canal treatment. Patients may also have a history of current/prior dental pain/toothache, thermal sensitivity of the teeth, or pain with attempted function (e.g., chewing). [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Panoramic radiograph showing decayed bilateral mandibular third molars and failed root canal treatment with periapical lesion related to the right mandibular first molar (middle arrow); also shows carious bilateral mandibular third molars on both sidesFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends].

Periodontal abscess:

Most patients have a history of gingivitis, periodontal (gum) disease, bleeding gums, bone loss, mobile teeth, gingival recession, and periodontal pocketing with increased probing depths. Dental probing is done by a dental professional to check the depth of the gingival sulcus that surrounds the tooth. Probing depths >3 mm indicate periodontal pocketing consistent with periodontal disease.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Panoramic radiograph showing generalized advanced horizontal periodontal bone loss with periapical radiolucency (see arrow) related to left mandibular first molar consistent with combined endodontic/periodontal abscessFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson; used with permission [Citation ends].

Pericoronal abscess (pericoronitis):

Frequently occurs in younger patients related to impacted/partially erupted lower wisdom teeth. Most patients have a history of a partially or incompletely erupted tooth, often with an overlying soft tissue flap (operculum), which makes access for oral hygiene difficult. This can lead to subsequent development of decay. In many cases, due to lack of functional contact, the opposing tooth will supraerupt, which can lead to recurrent mechanical trauma of the opposing operculum.

In some cases, the etiology can be multifactorial. In this situation, a thorough history (including compromising medical conditions, alcohol/drug use [e.g., methamphetamine], prior head and neck radiation exposure, and current and past medication use) is critical to the diagnosis and subsequent treatment course.

A thorough directed medical history is important to identify secondary compromising medical conditions early, because what may be a relatively mild infection in a healthy person can quickly progress to a very serious condition in a patient with reduced host defense mechanisms.

Comorbid conditions to be aware of include: malnutrition, diabetes, hepatic or renal disease, cystic fibrosis, chronic lung disease, heart failure, prior organ transplantation, alcohol and/or drug misuse, HIV infection/AIDS, collagen vascular disease, metastatic cancers, recent splenectomy, and medication use (e.g., immunosuppressants, cytotoxic agents, corticosteroids, recent or chronic antibiotic use). Consideration should be given to the effect of extremes of age.

Symptoms

Oral symptoms:

Dental pain/toothache: the most common presenting symptom. A history of prior pain may be a historical clue for a periapical abscess. With a periapical abscess, pain typically precedes swelling; with a periodontal abscess, swelling will usually precede pain. Multiple factors affect the severity of pain, including anatomic location, medications the patient may be taking, and the patient’s psychological state. Absence of dental pain or toothache should direct the clinician to consider alternative etiologies

Halitosis or bad taste in the mouth: patients commonly report halitosis or a bad/bitter taste in their mouth

Xerostomia: may be related to other symptoms that limit oral intake (e.g., dysphagia, trismus), prior radiation of the head and neck, salivary gland disease, or an adverse effect of medication (e.g., antihistamines, anticholinergics, antidepressants, antipsychotics)

Intraoral and/or extraoral edema or erythema: course of edema can be variable from slow progression over a number of days to becoming severe in a matter of a few hours. When the swelling starts over or near the root apex and is preceded by pain, it is more likely to be a periapical abscess. With a periodontal abscess, the swelling tends to start closer to the gingival margin and typically precedes the pain.

Systemic symptoms:

Fever or chills: with progression of the infection, patients will frequently have a history of fevers/chills.

With further progression, there may be more concerning symptoms (e.g., sore throat, trismus, dysphagia, drooling, dyspnea, altered speech, or altered mental status). The presence of these symptoms indicates a more serious or aggressive infection that requires prompt evaluation and operative treatment.

Physical exam

The physician should examine soft tissues of the head and neck, as well as inside of the mouth, for the following signs.

Edema:

Edema is common and may be intraoral and/or extraoral

Location and whether the swelling is fluctuant or nonfluctuant is important to note. Fluctuance indicates localized pus accumulation, and may be a good site to obtain an aspirate for culture. Cellulitis is generally nonfluctuant

Erythema with warmth to touch may be an early clinical sign that precedes edema or that may be seen concurrently with visible or palpable edema.

Purulent drainage:

May be intraoral and/or extraoral

Tends to develop via a fistula (parulis) near the apex of the involved tooth in a periapical abscess. With a periodontal abscess, drainage is more likely to develop via the periodontal pocket[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Panoramic radiograph with gutta percha tracking of intraoral fistula; shows large periapical radiolucency related to failed root canal treatment (note the multiple root canal-treated teeth)From the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends].

As infections progress to involve multiple fascial spaces, spontaneous drainage may develop and occurs via the path of least resistance.

Trismus:

A decreased ability to fully open the mouth may be noted, as some odontogenic infections involve the muscles of mastication, floor of the mouth, and neck

Normal mouth opening typically ranges from 35 to 45 mm. An interincisal opening of <10 mm suggests severe trismus, while an opening of 10 to 20 mm indicates moderate trismus, and 20 to 30 mm indicates mild trismus[34]

May limit the physician’s ability to perform an intraoral exam

Can limit oral intake and, in severe cases, affect the patient’s nutritional and hydration status

A significant indicator of severe infection.[15]

Uvular deviation:

Seen with a lateral pharyngeal space infection with the tonsil, lateral pharyngeal wall, and uvula being deflected to the opposing side

Patients will typically also have an extremely sore throat and mild trismus

A very concerning sign for impending airway impairment

Uvular deviation without a pharyngeal space infection indicates cranial nerve IX dysfunction, which is often seen with a stroke.[20] The uvula will deviate to the opposite side of the lesion.

Floor of mouth elevation:

Patients often report difficulty swallowing, or extending their tongue

May be seen with an abscess above the mylohyoid muscle involving the sublingual space. There may be no external swelling if only the sublingual space is involved; however, it is often associated with the adjacent submental or submandibular spaces (Ludwig angina). It is also seen with a hematoma, seroma, or a mass involving the sublingual space.[20] Concerning sign for impending airway impairment.

Dental examination may reveal the following:

Acute tooth percussion sensitivity: can be a clinical clue to the teeth involved. Although not a hard and fast rule, typically, a periodontal abscess will be more tender with lateral percussion and a periapical abscess will be more tender to apical (vertical) percussion

Thermal hypersensitivity: suggests a periapical abscess

Signs of periodontal disease: mobile teeth, deep periodontal pockets or bleeding on probing, receding gums, or bone loss around teeth may be present

Elevated or extruded tooth: common with a periapical abscess.

Patients who show any substantial signs of respiratory difficulty require immediate evaluation and intervention to prevent full respiratory obstruction. Signs of impending airway obstruction include:

Dysphagia, drooling, or dysphonia: suggests involvement of deeper structures in the hypopharynx and the potential for impending airway obstruction; dysphagia is a significant indicator of severe infection[15]

Tachypnea, respiratory stridor, or dyspnea: signs of acute airway compromise

Posturing: a serious sign seen with partial airway obstruction in which patients may position themselves to try to straighten the airway and allow poorly controlled secretions to move outward and away from the airway.

Patients may also present with signs of sepsis or shock (e.g., hypotension, tachycardia, pallor, weakness, diaphoresis, loss of skin turgor, dry mucous membranes) in severe infections. See Sepsis in adults.

Fascial space exam

It is important to determine what anatomic areas and/or fascial spaces are involved and the degree of involvement. A full description of the boundaries of specific spaces is beyond the scope of this topic; however, an important factor that determines what anatomic structures or fascial spaces are involved is the location at which an infective process penetrates the maxilla or mandible in relation to muscle attachments.

High-risk areas include the fascial planes of the neck, and the parapharyngeal, temporal, periorbital, pterygomandibular, or parotid spaces.[20] These high-risk areas are at greater risk for serious potential complications such as airway involvement, eye involvement, brain abscess, or cavernous sinus thrombosis. Multiple fascial space involvement is considered high risk for complications.

Moderate-to-severe risk areas include the soft palate, submental, sublingual, submandibular, submasseteric, peritonsillar, mentalis, and infraorbital spaces.

Lower-risk areas are localized to the jaw and include the hard palate, maxillary and mandibular alveolar ridge, or vestibule.

Investigations

Investigations should not delay emergent operative intervention to secure the airway when there are signs or symptoms of impending airway compromise.

Routine investigations

Standard laboratory investigations and a computed tomography (CT) scan are often obtained routinely in patients presenting to the emergency department with signs and symptoms of a dental abscess; however, for the majority of patients without other comorbid conditions, a complete blood count with differential and panoramic radiograph (if available) are adequate for the initial workup.

A panoramic radiograph (with or without periapical radiographs) assists with determining the source of the infection. An elevated white blood cell count is seen in most cases of acute dental abscess.

Serum electrolytes are deranged in severe infections or sepsis. C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and plasma fibrinogen level may also be elevated. Use CRP ahead of ESR to assess for inflammation in the acute phase because CRP is more sensitive and specific in this setting.[35]

Blood cultures are rarely helpful in guiding management; however, surgical site cultures should be taken as these guide antibiotic treatment.

A CT scan of the head and neck (with contrast) may be helpful in determining whether a local fluid collection is present, and may also help in planning the operative approach; however, it is not necessary initially in most cases.

Other investigations

An MRI of the head and neck is rarely indicated. Ultrasound of the fascial spaces is used in some countries; however, it is not common in the US.

Formal thermal testing and/or electric pulp testing can be performed by a dental professional to help verify the vitality status of a tooth, and to help localize the source of symptoms and infection prior to treatment with a root canal (or extraction when multiple teeth are suspect). With a periapical abscess, the involved tooth will be nonresponsive; whereas, the opposite is true with periodontal or gingival abscesses.

When medication-induced (e.g., bisphosphonate, denosumab) osteonecrosis of the jaw is suspected based on the medication history, C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide (CTX, a biologic index) can be used as a screening tool in conjunction with the history and exam. It measures bone remodeling and resorption.[36][37][38][39][40] Osteonecrosis can lead to loss of vitality of adjacent teeth with the development of associated dental abscess or infection. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Periapical radiograph showing large periapical radiolucency related to root canal-treated lateral incisor; final pathology was consistent with a periapical cystFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Panoramic radiograph showing periapical abscess related to the lower-left second molarFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends].

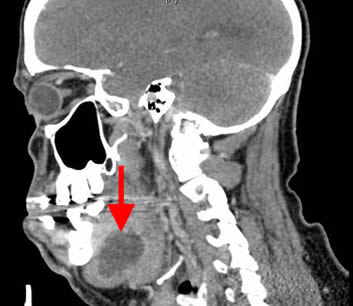

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Panoramic radiograph showing periapical abscess related to the lower-left second molarFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sagittal CT scan with contrast showing submandibular space abscessFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Sagittal CT scan with contrast showing submandibular space abscessFrom the personal collection of Melanie S. Lang and Thomas B. Dodson [Citation ends].

Differential diagnosis

Although oral and facial infections originating from dental abscesses are relatively common, it is important not to prematurely assume an oral or facial swelling is due to an odontogenic infection.

Other potential nonmicrobial or nonodontogenic sources should be considered early in the diagnostic workup of any oral or facial swelling, including edema due to facial trauma, viral sources (especially in children), benign and malignant neoplastic growths, developmental cysts, salivary gland inflammation, lymphadenitis, vascular malformations, and immunologic or autoimmune disorders.

Absence of dental pain should direct the clinician to consider alternative inflammatory etiologies.

Potential complications

Fascial space involvement can result in airway compromise.

Other high-risk findings include: rapid progression of edema, trismus, tongue elevation with inability to protrude the tongue, floor of mouth edema, voice changes, stridor, neurosensory changes, unrelenting fever, uvular deviation, lack of salivary control/drooling, volume depletion, decreased level of consciousness, and abnormal eye signs such as proptosis, pupillary dilation, diplopia, papilledema, and ophthalmoplegia.

Although rare, chest pain may suggest a descending neck infection and impending mediastinitis.

Central nervous system (CNS) changes are also rare and suggest a brain abscess due to hematogenous spread or direct extension into the CNS, producing a cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer