Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion of granulomatous lung diseases, including tuberculosis and histoplasmosis. Typical history is essential and biopsy from affected organs is often required to establish the diagnosis.[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr 15;201(8):e26-51.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32293205?tool=bestpractice.com

Diagnostic goals are as follows:[14]American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;160(2):736-55.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10430755?tool=bestpractice.com

Histologic confirmation (may be necessary for nontypical clinical presentation or computed tomography [CT] appearance)

Assessment of the extent and severity of organ involvement

Assessment of likelihood of progression

Determination of whether therapy will benefit the patient.

Certain clinical features are highly specific for the disease and are considered diagnostic, including Löfgren syndrome, lupus pernio, and Heerfordt syndrome.[31]Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr 15;201(8):e26-51.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32293205?tool=bestpractice.com

[32]Grunewald J, Eklund A. Sex-specific manifestations of Löfgren's syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Jan 1;175(1):40-4.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.200608-1197OC

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17023727?tool=bestpractice.com

[33]Spiteri MA, Matthey F, Gordon T, et al. Lupus pernio: a clinico-radiological study of thirty-five cases. Br J Dermatol. 1985 Mar;112(3):315-22.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2983750?tool=bestpractice.com

[34]Poate TW, Sharma R, Moutasim KA, et al. Orofacial presentations of sarcoidosis - a case series and review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2008 Oct 25;205(8):437-42.

https://www.nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2008.892

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18953304?tool=bestpractice.com

History

Diagnosis is more common among those with a family history of sarcoidosis.[19]Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, et al; ACCESS Research Group. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis: a case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Dec 1;164(11):2085-91.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2106001

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11739139?tool=bestpractice.com

[20]Rossides M, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Familial aggregation and heritability of sarcoidosis: a Swedish nested case-control study. Eur Respir J. 2018 Aug 16;52(2):1800385.

https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/52/2/1800385

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29946010?tool=bestpractice.com

[21]Sverrild A, Backer V, Kyvik KO, et al. Heredity in sarcoidosis: a registry-based twin study. Thorax. 2008 Oct;63(10):894-6.

https://thorax.bmj.com/content/63/10/894

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18535119?tool=bestpractice.com

There is a higher incidence in people of Scandinavian origin.[8]Grunewald J, Grutters JC, Arkema EV, et al. Sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Jul 4;5(1):45.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31273209?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Arkema EV, Cozier YC. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: recent estimates of incidence, prevalence and risk factors. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020 Sep;26(5):527-34.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7755458

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32701677?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;160(2):736-55.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10430755?tool=bestpractice.com

Pulmonary symptoms such as cough and dyspnea predominate. Costochondritis may also occur, resulting in chest wall pain.

Constitutional symptoms are common and include chronic fatigue, weight loss, and low-grade fever.[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

Other symptoms include photophobia and skin lesions.[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

[35]Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015 Dec;36(4):669-83.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4662043

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26593141?tool=bestpractice.com

Musculoskeletal manifestations, including arthralgia (affecting the knees, ankles, elbows, and wrists) occur in up to one third of people with sarcoidosis.[36]Bechman K, Christidis D, Walsh S, et al. A review of the musculoskeletal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018 May 1;57(5):777-83.

https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/57/5/777/4096668

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28968840?tool=bestpractice.com

[37]Sweiss NJ, Patterson K, Sawaqed R, et al. Rheumatologic manifestations of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Aug;31(4):463-73.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3314339

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20665396?tool=bestpractice.com

Many patients are, however, asymptomatic and sarcoidosis is only suspected on the basis of radiographic testing for an unrelated reason.

Chronic beryllium exposure and hypersensitivity pneumonitis should be considered in patients with a history of relevant occupational and/or environmental exposures.[31]Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr 15;201(8):e26-51.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32293205?tool=bestpractice.com

Physical exam

Chest signs may include wheezing/rhonchi due to airway involvement, mimicking asthma.[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

Lymph nodes are enlarged and nontender. Cervical, submandibular nodes are often involved. Rarely, lymphadenopathy is generalized.

Cardiac manifestations occur in 5% to 10% of cases and may present with arrhythmias or heart block.[3]Kouranos V, Sharma R. Cardiac sarcoidosis: state-of-the-art review. Heart. 2021 Oct;107(19):1591-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33674355?tool=bestpractice.com

[38]Cheng RK, Kittleson MM, Beavers CJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024 May 21;149(21):e1197-216.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001240

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38634276?tool=bestpractice.com

Pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure occur later in the course of the condition.[38]Cheng RK, Kittleson MM, Beavers CJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024 May 21;149(21):e1197-216.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001240

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38634276?tool=bestpractice.com

Palpable hepatomegaly occurs in 20% of people.[39]Tadros M, Forouhar F, Wu GY. Hepatic sarcoidosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2013 Dec;1(2):87-93.

https://www.xiahepublishing.com/ArticleFullText.aspx?sid=2&jid=1&id=10.14218%2fJCTH.2013.00016

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26357609?tool=bestpractice.com

The liver is usually nontender.

Erythema nodosum and lupus pernio are typical skin manifestations of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum presents as tender erythematous nodules on the lower extremities and is a predictor of a good prognosis. Lupus pernio presents as indurated plaques with discoloration of the nose, cheeks, lips, and ears. It is more common in black women and is a predictor of a poor prognosis.[14]American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;160(2):736-55.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10430755?tool=bestpractice.com

[40]Marchell RM, Judson MA. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010 Aug;31(4):442-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20665394?tool=bestpractice.com

Other skin lesions have been described, including scaly erythematous rash, and smooth papules.

Ocular sarcoidosis may present as anterior uveitis, optic neuritis, or conjunctival nodules. Anterior uveitis usually presents with red, painful eyes and blurred vision.[41]Rothova A. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Jan;84(1):110-6.

https://bjo.bmj.com/content/84/1/110

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10611110?tool=bestpractice.com

Neurosarcoidosis occurs in <15% of cases and may present with facial palsy and signs of pituitary lesions (e.g., diabetes insipidus). Headaches and seizures can also occur.[5]Lacomis D. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011 Sep;9(3):429-36.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3151597

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22379457?tool=bestpractice.com

Joint exam does not usually reveal synovial thickening.

Initial tests

There are several initial tests to perform in people with suspected sarcoidosis.[14]American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;160(2):736-55.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10430755?tool=bestpractice.com

[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

[31]Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr 15;201(8):e26-51.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32293205?tool=bestpractice.com

Chest x-ray: typically shows bilateral hilar and right paratracheal adenopathy, although isolated bilateral hilar adenopathy is more frequent. May show bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, predominantly in the upper lobes.

CBC: may reveal modest leukopenia or lymphopenia and anemia.

BUN and serum creatinine: may be elevated in the uncommon event of renal involvement.

Liver enzymes: liver function tests screen for hepatic sarcoidosis; US guidelines recommend baseline serum alkaline phosphatase testing.

Serum calcium: baseline serum calcium testing to screen for abnormal calcium metabolism. Hypercalcemia occurs due to the dysregulated production of calcitriol by activated macrophages and granulomas.

PFTs (including spirometry and gas transfer analysis): measure baseline lung function. Obstructive and restrictive defects in lung function may be found. PFTs are used to monitor any decline in lung function over time.

ECG: may show conduction abnormalities if there is any cardiac involvement.

Eye exam: baseline eye exam can help to identify ocular involvement, including in those without ocular symptoms.

Interferon gamma release assay: tuberculosis and atypical mycobacterial infections can mimic sarcoidosis. Interferon gamma release assay is used for screening, and preferable to tuberculin skin testing due to anergy. Interferon gamma release assays cannot distinguish between latent infection and active disease.

Serum ACE: a marker of active disease, elevated in many patients. ACE levels cannot be used for diagnosis and may not reflect disease activity. Utility is unreliable and controversial.[14]American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;160(2):736-55.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10430755?tool=bestpractice.com

Seek specialist advice if there is major extrapulmonary organ involvement, including ophthalmic review for patients with ocular symptoms, neurology review for central or peripheral nervous symptoms, and dermatology review for patients with skin lesions.[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bilateral hilar adenopathyFrom the collection of Dr M.P. Muthiah; used with permission [Citation ends].

Subsequent tests

Chest CT scan

Not necessary in the routine evaluation or management of sarcoidosis. Indications include atypical presentation or evaluation of complications (bronchiectasis, aspergilloma, pulmonary fibrosis, or a superimposed infection or malignancy).[42]Lynch JP 3rd. Computed tomographic scanning in sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Aug;24(4):393-418.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16088560?tool=bestpractice.com

Scans with contrast and high-resolution images show hilar and/or paratracheal adenopathy with predominantly upper lobe bilateral infiltrates. The infiltrates are classically in a perilymphatic distribution.

Endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscopy

Most patients with pulmonary symptoms, with no histologic diagnosis of sarcoidosis from extrathoracic sites, require bronchoscopy. In patients with suspected pulmonary sarcoidosis, diagnostic yield is superior with endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided transbronchial node aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) compared with conventional transbronchial lung biopsy.[43]von Bartheld MB, Dekkers OM, Szlubowski A, et al. Endosonography vs conventional bronchoscopy for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis: the GRANULOMA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013 Jun 19;309(23):2457-64.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1697962

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23780458?tool=bestpractice.com

[44]Gupta D, Dadhwal DS, Agarwal R, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration vs conventional transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2014 Sep;146(3):547-56.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24481031?tool=bestpractice.com

EBUS-TBNA is standard of care and routine practice for the diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy, with high sensitivity (88%) and specificity (100%).[45]Varela-Lema L, Fernández-Villar A, Ruano-Ravina A. Effectiveness and safety of endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009 May;33(5):1156-64.

https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/33/5/1156

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19407050?tool=bestpractice.com

[46]National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for mediastinal masses. Feb 2008 [internet publication].

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg254

[47]Agarwal R, Srinivasan A, Aggarwal AN, et al. Efficacy and safety of convex probe EBUS-TBNA in sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2012 Jun;106(6):883-92.

https://www.resmedjournal.com/article/S0954-6111(12)00082-0/fulltext

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22417738?tool=bestpractice.com

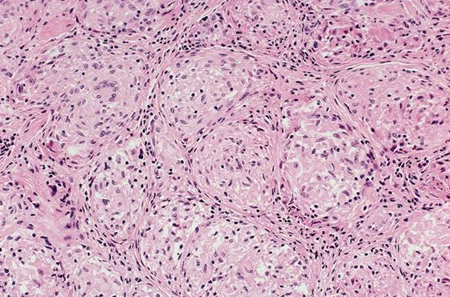

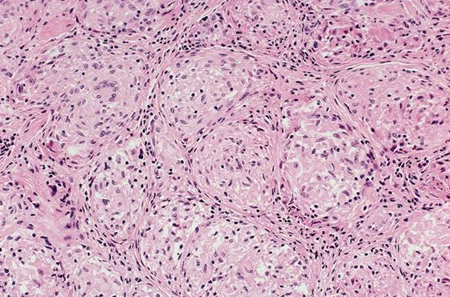

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Photomicrograph showing well-formed granulomas typical for sarcoidosisFrom the collection of Dr M.P. Muthiah; used with permission [Citation ends].

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is a useful adjunct; BAL may reveal lymphocytosis with a CD4-to-CD8 ratio >3.5.

Endobronchial biopsy and transbronchial biopsy can be performed. Transthoracic biopsy may be considered for peripheral lesions not accessible by bronchoscopy.

Biopsy shows noncaseating granulomas, with negative stains for acid-fast bacillus and fungi.

Skin lesion biopsy

Performed in people with lesions that are suspected to be manifestations of cutaneous sarcoidosis; reveals classic noncaseating granulomas.

24-hour urine calcium

May be ordered in patients with a history of renal calculi to rule out hypercalciuria, which, when present, can cause nephrocalcinosis with progressive renal insufficiency.

Gallium-67 scintigraphy

May be used when the diagnosis is in doubt. Serial images sometimes require 48 hours to complete. The clinical value of this test remains controversial.[30]Thillai M, Atkins CP, Crawshaw A, et al. BTS clinical statement on pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2021 Jan;76(1):4-20.

https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-statements/sarcoidosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33268456?tool=bestpractice.com

Gallium scans can show typical uptake patterns. These include the panda sign (lacrimal and parotid gland uptake) or the lambda sign (parahilar, infrahilar, and right paratracheal or azygos node uptake). Gallium-67 scintigraphy lacks specificity.

Vitamin D metabolism

If assessment of vitamin D metabolism is deemed necessary (e.g., to determine whether vitamin D replacement is indicated) measure both 25- and 1,25-OH vitamin D levels before vitamin D replacement.[31]Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Apr 15;201(8):e26-51.

https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32293205?tool=bestpractice.com

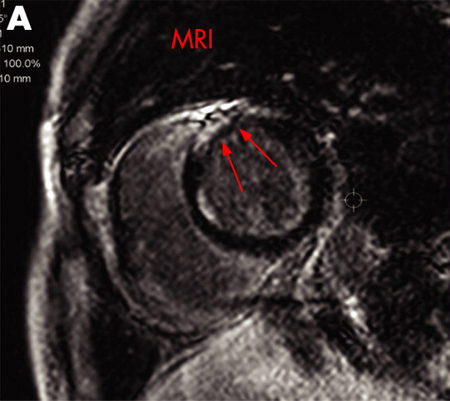

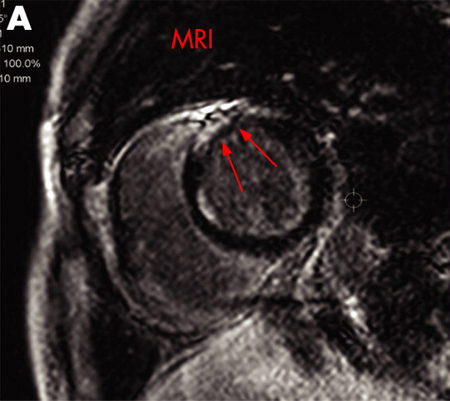

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

May be used to identify areas of sarcoidosis involvement including the heart and the brain.[48]Nunes H, Brillet PY, Valeyre D, et al. Imaging in sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Feb;28(1):102-20.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17330195?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A) Gadolinium-enhanced MRI scan of the heart (short axis) showing delayed enhancement in the anteroseptal myocardiumAdapted from https://casereports.bmj.com/content/2009/bcr.2006.070805.full [Citation ends].

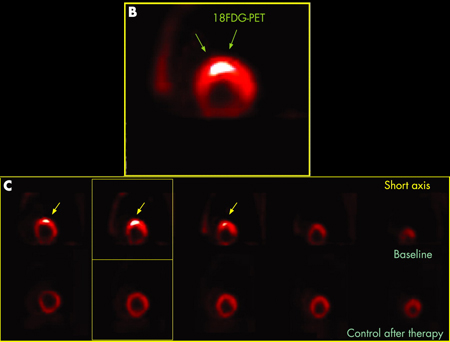

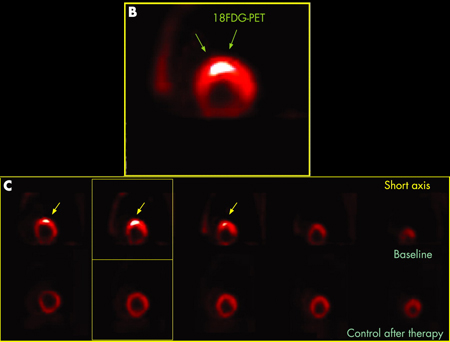

(18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET)

Demonstrates a characteristic pattern of uptake in sarcoidosis and may aid in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.[38]Cheng RK, Kittleson MM, Beavers CJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024 May 21;149(21):e1197-216.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001240

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38634276?tool=bestpractice.com

[49]Youssef G, Leung E, Mylonas I, et al. The use of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis including the Ontario experience. J Nucl Med. 2012 Feb;53(2):241-8.

https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/53/2/241

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22228794?tool=bestpractice.com

[50]Chareonthaitawee P, Beanlands RS, Chen W, et al. Joint SNMMI-ASNC expert consensus document on the role of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in cardiac sarcoid detection and therapy monitoring. J Nucl Med. 2017 Aug;58(8):1341-53.

https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/58/8/1341

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28765228?tool=bestpractice.com

This test is much less invasive than endomyocardial biopsy, with minimal to no complications from the procedure.[51]Nobuhiro T, Atsuko T, Yoshikazu N, et al. Heterogeneous myocardial FDG uptake and the disease activity in cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010 Dec;3(12):1219-28.

https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.09.015

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21163450?tool=bestpractice.com

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: B) 18F-FDG PET scan of the heart (short axis) showing focal uptake in the anteroseptal wall corresponding to granulomatous inflammation. (C) 18F-FDG PET scan of the heart (short axis) from the base to the apex (from left to the right) showing focal uptake in the anteroseptal wall at baseline (upper series) and disappearance of the uptake after treatment (lower series)Adapted from https://casereports.bmj.com/content/2009/bcr.2006.070805.full [Citation ends].

Emerging tests

Newer applications of PET include 3'-deoxy-3'-[18F]-fluorothymidine or 4' [methyl-11C]-thiothymidine imaging.[52]Martineau P, Pelletier-Galarneau M, Juneau D, et al. Imaging cardiac sarcoidosis with FLT-PET compared with FDG/perfusion-PET: a prospective pilot study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019 Nov;12(11 pt 1):2280-1.

https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.06.020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31422126?tool=bestpractice.com

[53]Hotta M, Minamimoto R, Kubota S, et al. 11C-4DST PET/CT imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis: comparison with 18F-FDG and cardiac MRI. Clin Nucl Med. 2018 Jun;43(6):458-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29538030?tool=bestpractice.com

Unlike 18F-FDG PET, these imaging techniques do not require any dietary restriction.