Approach

Clinical appearance is important for diagnosis. The appearance of the oral lesions varies, depending on the type of candidiasis.

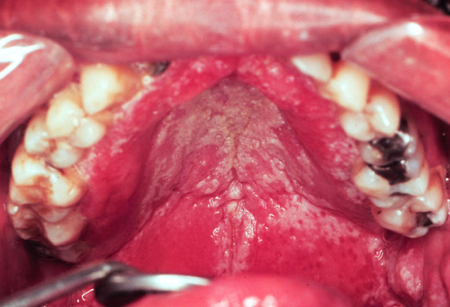

Pseudomembranous candidiasis

These lesions are creamy white or yellowish plaques, and are fairly adherent to oral mucosa. One helpful clinical feature of the pseudomembranous type is the ability to scrape off the superficial white plaques. Removal of the plaque, by scraping, may reveal an erythematous base or a bleeding surface. Although the lesions may occur anywhere on the oral mucosa, they most commonly present on the palate, buccal mucosa, and the dorsum of the tongue. Symptoms are typically mild and may include a burning sensation and unpleasant taste in the mouth (typically described as salty or bitter).[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pseudomembranous candidiasis in diabetesFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pseudomembranous candidiasis in HIVFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pseudomembranous candidiasis in HIVFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

Erythematous candidiasis

This type of candidiasis is more common than pseudomembranous candidiasis but is often overlooked clinically. Lesions are fiery red, flat, atrophic on the palate, and appear as patchy areas of loss of filiform papillae on the dorsum of the tongue, or as spotty red areas on the buccal mucosa. There is often no white component, or if a white component is present, it is not a prominent feature. Patients with erythematous candidiasis often complain of oral tenderness and a burning sensation.[1]

Denture stomatitis

This is found in association with removable dental prostheses. It is characterized by varying degrees of erythema that are confined to the outline of the prosthesis, and may be accompanied by petechial hemorrhage. Patients with denture stomatitis are typically asymptomatic.[1][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Candidiasis under a maxillary partial dentureFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

Angular cheilitis

The typical appearance of angular cheilitis is that of cracks, ulcers, or crusted fissures, radiating from the corners of the mouth. These lesions are frequently moderately painful. It is often seen among older people with loss of vertical dimension at the corners of the mouth.[1]

See Angular cheilitis.

Less common types

Less common types of candidiasis may have alternative specific presentations. Median rhomboid glossitis lesions (also known as central papillary atrophy) are asymptomatic and have a well-demarcated rhomboid outline on the central dorsal aspect of the tongue.[1]

Linear gingival erythema is another uncommon type. Lesions present as a continuous or patchy band of erythema, involving the free gingival margin.[2][3][4] The lesions are persistent, despite removal of plaque and improvement of home oral care.

Identification of risk factors

In many circumstances, risk factors may be evident from history or examination, such as known HIV infection, hyposalivation/xerostomia, use of dentures, malnutrition, advanced malignancy, cancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy, pregnancy, or recent immunosuppressive or antibiotic therapy. In the absence of overt risk factors, the following investigations may be indicated in adults with oral candidiasis:

Urinalysis, random or fasting blood glucose, or glucose tolerance test to exclude diabetes

HIV test

Sialometry

Electrolyte panel to exclude endocrinopathy (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypoparathyroidism, pregnancy, hypoadrenalism).

Even when patients with known medical risk factors for oropharyngeal candidiasis do not present with oral symptoms, a physical exam is recommended to establish whether asymptomatic lesions are present. This is especially important for immunocompromised patients, where oropharyngeal candidiasis, if untreated, may become focally invasive or disseminate.

Laboratory tests

Diagnosis of oral candidiasis is made through microscopic examination of superficial smear samples. A potassium hydroxide wet mount can be prepared in the physician's office and the slide viewed with a microscope directly. This is often the first investigation. However, where the physician does not have the facilities in the office to perform this test, or if a more permanent record of the test is required, the smear sample may be sent to the laboratory, requesting a periodic acid-Schiff stain of fixed scrapings from the lesions, for microscopic visualization of the Candida yeast form or hyphae. In erythematous candidiasis, superficial Candida hyphae are few, but in pseudomembranous forms they are numerous, and more likely to result in a positive smear test.

If the smear sample is negative for Candida, this may be due to an inadequate smear sample or an infection that has invaded deep into the tissue. In this situation, a biopsy of a lesion may be performed. Histologic examination of tissue samples demonstrate Candida hyphae, extending into the spinous cell layer of the epithelium, with marked parakeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiosis, as well as a submucosal neutrophil response.[24]

Culture of a mouth rinse sample may be used for mycologic surveillance, to determine the level of candidal carriage and risk of infection among patients who would not otherwise receive prophylactic antifungal therapy.[15] It is not usually indicated for cases of oral candidiasis where diagnosis is possible by clinical presentation or by smear exam. Candida is present in the normal flora, so when culture is performed, moderate to heavy growth of yeast should be considered for intervention.[53] This equates to approximately ≥400 colony-forming units/mL.

In vitro susceptibility testing is usually not indicated for oropharyngeal candidiasis, but is most helpful in dealing with refractory infection due to non-albicans species of Candida.[54]

Identification of invasive disease

Oropharyngeal candidiasis may be associated with esophageal candidiasis, especially in the setting of HIV infection.[55] Therefore, patients who present with signs and symptoms such as retrosternal burning, dysphagia or odynophagia should be evaluated for possible esophageal involvement. Although the diagnosis may be established through empirical treatment based on symptoms and response to therapy, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy may become necessary to determine if in fact the patient has esophageal involvement. Diagnosis may involve direct visualization of plaques or surface ulceration of the esophageal mucosa and fungal smear. Definitive diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis requires histopathologic examination of the biopsy samples and confirmation by fungal culture and speciation.[17]

For more information on esophageal candidiasis in people living with HIV, see HIV-related opportunistic infections.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer