Etiology

Candida species are considered normal flora in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts in humans, as well as fungal pathogens.[22] Pathologic colonization is linked to factors including age extremes and compromised immunity.[22]

Most cases of oropharyngeal candidiasis are due to C albicans. This is a dimorphic fungus, consisting of spherical or ovoid yeast cells, or elongated hyphal forms.[1][22] Although both yeast and hyphal forms may be seen with Candida infection (especially in erythematous types), it is the hyphal form that is usually associated with invasion of host tissue.[22]

A small subset of cases are due to one or more alternative species, such as C glabrata, C tropicalis, C pseudotropicalis, C parapsilosis, C guilliermondii, C krusei, or C dubliniesis, C lusitaniae, and C auris.[22] In patients with recurrent infection, strain replacement with a new genotype of C albicans or species replacement with a non-albicans species of Candida may occur.[21] It is well established that these changes will lead to the development of refractory infection and especially azole resistance.[23]

Pathophysiology

Establishment of infection requires a number of events, including thigmotropism (contact sensing) and attachment to epithelial cells, as well as intercellular penetration through secretion of protease enzymes, more specifically secretory aspartyl proteinases and phospholipase B.[24][25]

The ability of Candida to colonize and infect oral tissues requires specific local and systemic defects in the host immune responses. Among healthy people, several immunologic and nonimmunologic defense mechanisms are collectively responsible for the antifungal properties of the oral environment. Among these are:

Several special properties of saliva (see below)

The presence of antimicrobial proteins

Candidal growth inhibition by oral keratinocytes

T-cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity response to C albicans.[21][26]

The nonimmunologic aspects of saliva include:

Mechanical debridement, facilitated by salivary mucins and proteoglycans

A close to neutral pH that reduces fungal adherence to epithelial surfaces and reduces the expression of C albicans virulence genes

Antibacterial proteins such as lysozyme, lactoferrin, histatins, calprotectin, and secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor.[21]

Saliva also contains Candida-specific salivary secretoryim IgA and IgA, but their overall effectiveness in inhibiting candidal growth in immunocompromised people is not clear.[27]

Keratinocytes not only provide a physical barrier to C albicans infection but also secrete a number of growth factors and cytokines. These play a critical role in the inflammatory response on the epithelial surface.[28][29]

Lastly, an intact T helper cell 1 (Th1) CD4+ response to C albicans and a CD4+ T-cell augmentation of monocyte/macrophage and polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions appear to be necessary for the clearance of oropharyngeal candidiasis.[21][30]

C albicans is able to transition from its commensal to pathogenic form largely through biofilm formation.[22]

Classification

Commonly accepted clinical classification by type

Pseudomembranous[1]

Commonly known as "thrush".

Associated with antibiotic therapy and immunosuppression.

Involves opportunistic fungal invasion of the most superficial layers of the squamous mucosa.

Appears as creamy white or yellowish plaques that are fairly adherent to oral mucosa.

Removal of the plaque, by scraping, may reveal an erythematous base or a bleeding surface.

Most commonly found on the buccal mucosa, dorsal tongue, and palate.

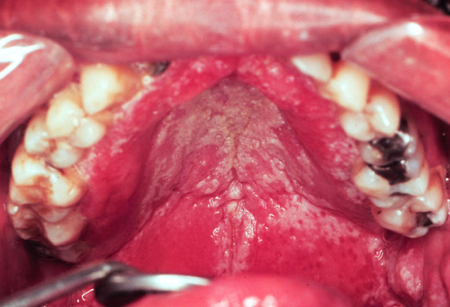

Clinical course may be acute or chronic.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pseudomembranous candidiasis in diabetesFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pseudomembranous candidiasis in HIVFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Pseudomembranous candidiasis in HIVFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

Erythematous[1]

More common than pseudomembranous candidiasis although often overlooked clinically.

May be associated with antibiotic therapy, immunosuppression, or xerostomia, or may arise spontaneously.

No white component, or if present, white component is not a prominent feature.

Appears as atrophic, fiery red flat lesions on the palate, patchy areas of loss of filiform papillae on the dorsum of the tongue, or spotty red areas on the buccal mucosa.

The clinical course may be acute or chronic.

Denture stomatitis[1]

Seen under removable prostheses.

Related to patients wearing their dentures continuously with minimal cleaning.

Remains controversial as may not be due to Candida infection; denture is often positive on culture but mucosa is not. Could result from tissue response to pathogens living beneath the denture.

The appearance of the lesion may be smooth and velvety or nodular.

Characterized by varying degrees of erythema that are confined to the outline of the prosthesis.

May be accompanied by petechial hemorrhage. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Candidiasis under a maxillary partial dentureFrom the collection of Fariba Younai, UCLA School of Dentistry, Los Angeles [Citation ends].

Angular cheilitis[1]

Consists of cracks, ulcers, or crusted fissures radiating from angles of the mouth.

May be associated with immunosuppression or loss of vertical dimension, or may arise spontaneously.

Loss of vertical dimension is typically seen among older people. Saliva pools in deep folds at the corners of their mouth, creating a moist environment favoring a yeast infection.

Also seen in several types of vitamin and nutritional deficiency states.

Clinically, the lesions are moderately painful.

Less common types

Median rhomboid glossitis (also known as central papillary atrophy)[1]

A form of candidiasis seen as an erythematous area with a rhomboid outline on the central dorsal aspect of the tongue.

May be associated with immunosuppression or may arise spontaneously.

This lesion is usually symmetrical and the surface may be smooth or lobulated.

Hyperplastic (also known as candidal leukoplakia)[1]

This form of oral candidiasis is the least common and considered somewhat controversial. Some believe that it is caused by Candida superimposing onto existing keratotic lesions; however, others believe that Candida are capable of inducing a hyperkeratotic lesion alone.

May appear as a white patch that cannot be rubbed off; in this case the term chronic hyperplastic candidiasis is appropriate.

If appearing with mixed red and white areas (speckled), may have dysplastic potential.

May be associated with immunosuppression or may arise spontaneously.

Linear gingival erythema (LGE)

LGE is a specific HIV-related periodontal manifestation.

Presents as a continuous or patchy band of erythema involving the free gingival margin.[2][3][4]

Lesions are persistent, despite removal of plaque and improvement of home oral care.

LGE is related to the invasion of the gingival tissues by C albicans and the advancement of periodontal tissue breakdown that also correlates with advancing HIV disease.

Mucocutaneous candidiasis[1]

Rare condition associated with sporadic, or more rarely inherited, immune dysfunction.

Usually presents with thick white plaques that do not rub off and areas of redness on the tongue, buccal mucosa, and palate.

May be associated with endocrine abnormalities including hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, hypoadrenalism, and diabetes mellitus.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer