Etiology

Bronchiectasis has many different causes. Recurrent pulmonary infection leads to progressive bronchial damage. The assessment and determination of an underlying etiology determine the treatment as well as prognosis of this disease. The etiology falls into the following categories:

Post-infectious (around 18% of adult patients):[12]

Prior childhood respiratory infections due to viruses (e.g., measles, influenza, pertussis)

Prior infections with Mycobacteria or severe bacterial pneumonia

Swyer-James or Macleod syndrome (a chronic manifestation of bronchiolitis or pneumonitis in childhood, characterized by unilateral pulmonary hypoplasia and radiographic hyperlucency).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; around 15% of adult patients).[12]

Asthma (around 7% of adult patients).[12]

Connective tissue disorders (around 9% of adult patients):[12]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Sjogren syndrome.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (around 5% of adult patients):[12]

Exaggerated response to inhaled Aspergillus fumigatus.

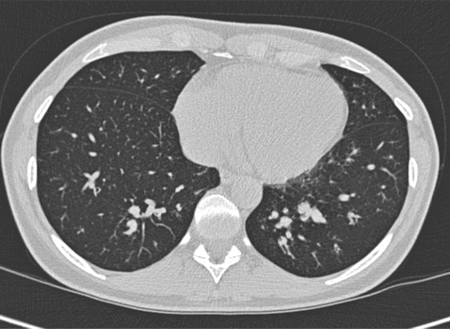

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Mucus-impacted bronchi in a 36-year-old woman with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosisFrom Pamela J. McShane, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Immunodeficiency (around 5% of patients):[12]

Immunoglobulin deficiency

HIV infection.

Aspiration or inhalation injury (around 4% of adult patients).[12][15]

Genetic:

Cystic fibrosis

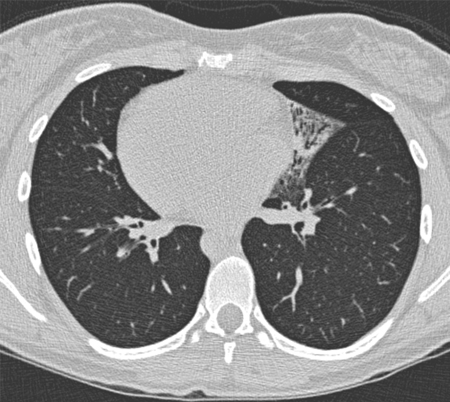

Ciliary dyskinesia or immotile cilia syndrome with or without Kartagener syndrome (an autosomal-recessive condition characterized by the clinical triad of bronchiectasis, situs inversus, and chronic sinusitis [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Situs inversus (Kartagener syndrome) in a 19-year-old woman with focal bronchiectasis from primary ciliary dyskinesiaFrom Pamela J. McShane, MD; used with permission [Citation ends].

Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Inflammatory bowel diseases:

Ulcerative colitis

Crohn disease.

Focal bronchial obstruction:

Foreign body

Broncholith

Stenosis

Tumor

Adenopathy with extrinsic compression.

Other:

Mounier-Kuhn syndrome (also known as tracheobronchomegaly, characterized by abnormal dilation of the trachea and main bronchi)

Williams-Campbell syndrome (also known as tracheomalacia, characterized by absence or weakness of bronchial cartilage, leading to bronchial collapse)

Yellow nail syndrome

Pulmonary sequestration

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Marfan syndrome

Young syndrome (a condition, believed to be genetic, characterized by obstructive azoospermia with normal sperm production plus chronic or recurrent sinus and lung infections)

IPEX (Immune dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked)-like syndrome[16]

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides[17]

Infection by human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1).[18][19]

Idiopathic (up to 29% of patients).[12]

In children, the most common causes of noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis are infection (4% to 36%), asthma (40%), immunodeficiency (10% to 34%), aspiration (4% to 22%), and primary ciliary dyskinesia (2% to 24%). In low-income countries, there is a higher incidence of recurrent protracted bacterial bronchitis and post tuberculosis bronchiectasis. Idiopathic bronchiectasis is diagnosed in a high proportion of cases but, as underlying cause affects management (e.g., in the case of immunodeficiency), it should only be considered after full investigation for possible etiologies.[20]

There are identifiable causes of bronchiectasis in many patients worldwide, especially bronchiectasis that is due to prior infection. However, the cause of bronchiectasis may not be identified, and hence the condition is often considered to be idiopathic.

Exacerbations of bronchiectasis have been postulated to be caused by novel strains of bacteria in the airways, increased density of bacteria, or both.[21] This is because antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of bronchiectasis reduces clinical symptoms, restores lung function, and suppresses inflammatory responses. However, a cohort study of 119 adults with bronchiectasis found that viral infections were more prevalent in exacerbations than in steady-state bronchiectasis, suggesting that viruses play a role in triggering exacerbations of bronchiectasis.[22]

Pathophysiology

The dilation and thickening of the bronchi seen in bronchiectasis are due to chronic inflammation elicited by the host response to microorganisms colonizing the airways. This persistent airway inflammation leads to the subsequent development of bronchial wall edema and increased mucus production. Several inflammatory cells including neutrophils, T lymphocytes, and other immune effector cells are recruited to the airways and subsequently release inflammatory cytokines, proteases, and reactive oxygen mediators implicated in the progressive destruction of the airways.[23][24][25]

This initial insult to the airways by the primary infection leads to increased inflammation, resulting in bronchial damage, and serves as a nidus for subsequent colonization of the airways. As a result, a vicious cycle ensues that predisposes to persistent bacterial colonization and to a subsequent chronic inflammatory reaction that eventually leads to progressive airway damage and recurrent infections.

The factors that predispose individuals with an initial infection to go on to develop bronchiectasis remain unclear.

Classification

Morphologic classification: Reid classification of bronchiectasis[2]

Three morphologic types were described in 1950 by Dr. Lynn Reid. Though not clinically useful, classification into morphologic types provides insight into pathophysiology and useful descriptive terminology. Studies have shown that the cystic morphology is more likely to be associated with Pseudomonas colonization and more sputum production than the other types.

Cylindrical bronchiectasis:

Bronchi enlarged and cylindrical in shape

Normal tapering of airway as it traverses to the periphery is not present

Distal airways end abruptly, owing to mucus plugging

Fewer generations of bronchi than normal

Parallel tram-track lines are seen on chest x-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan

CT cross-section views reveal "signet ring" appearance of the dilated bronchus and its accompanying vessel.

Varicose bronchiectasis:

Irregular bronchi, with alternating dilation and constriction

Bronchographic pattern resembles varicose veins.

Saccular or cystic bronchiectasis:

Most severe form

Commonly found in cystic fibrosis patients

Bronchi are dilated, forming a cluster of round air-filled or fluid-filled cysts

Only 25% of the normal number of bronchial subdivisions

Degree of bronchial dilation increases proximal to distal

Bronchial tree ends in blind sacs.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer