Approach

Clinically, a rash may be categorised as maculopapular, pustular, vesiculobullous, diffuse/erythematous, or petechial/purpuric in nature. However, in many aetiologies these forms may co-exist or evolve from one form to another. Diagnosis should focus on exclusion of urgent considerations first, as these are likely to require prompt intervention. Associated symptoms and contact with other children with similar symptoms may help to elucidate the cause.

Initial considerations

Initial considerations include morphology, duration, and distribution of the rash, together with an association with other systemic symptoms. Age, sex, family history, medications, known allergies, and exposures are also of primary importance. Patients or their parents or guardian, may reveal the cause of the rash in their historical recollection of events before its appearance (e.g., a parent may report that several children in the neighbourhood who have been unwell with a 'bug' then develop a rash: hand-foot-and-mouth disease, measles, or scarlet fever).

A full history should include current and previous medications; existing systemic conditions; possible exposure to infection; and social, recreational, and travel information. Contact with people with existing conditions such as impetigo or scabies, and viral infections such as chickenpox, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), roseola infantum (sixth disease), Mpox, and hand-foot-and-mouth disease may help to confirm the diagnosis. Any history of pharyngitis (as a source of streptococcal infection) should be noted. Any recent illness associated with a sore throat or upper respiratory tract infection suggests a viral illness. For all viral exanthems, fever, malaise, pharyngitis, and myalgia are commonly associated symptoms.

Examination of the primary lesion should include type of rash, its extent, and distribution. Involvement (or sparing) of the mucous membranes should be noted. A full systemic examination should record any associated features such as pyrexia, pruritus, lymphadenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly. Generally, rash in the absence of fever or systemic symptoms is not urgent. When fever or signs of illness are present, urgent assessment and treatment must be considered. The differential diagnosis is extensive, ranging from self-limiting conditions (e.g., roseola) to life-threatening illnesses such as meningococcal disease. Several systemic conditions with rash may have a serious clinical course, and these should be assessed urgently if suspected (see below).[92]

For many childhood rashes, diagnosis is clinical, and tests are not routinely recommended. However, laboratory investigations may be appropriate in patients in whom the cause is not clear. In a rash suspected to be caused by a drug, no laboratory tests to determine or confirm the responsible drug are readily available. Full blood count (FBC) may show only mild to moderate peripheral eosinophilia. Metabolic, hepatic, and renal function panels are usually normal. The diagnosis of viral exanthema, depending on the particular virus involved, may need to be confirmed by serologically demonstrable antibody titres, viral culture, or molecular studies (e.g., polymerase chain reaction). Patients with suspected HIV exanthem will screen positive for HIV viral RNA or core antigen. All patients with more significant clinical disease, including serious bacterial infections, or with extracutaneous findings require a more complete work-up.

Unwell child: systemic involvement

Erythematous rash

Possible diagnoses include urticaria due to hypersensitivity, scarlet fever, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), toxic shock syndrome (TSS), early stages of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), rheumatic fever, juvenile arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoidosis, and Lyme disease.

Hypersensitivity reactions

Generalised urticaria is a feature. If insect bites are the trigger, localised lesions, usually on unclothed areas of the skin, may also be seen. An urticarial eruption occurs within minutes to hours of exposure to an allergenic agent. Each individual urticarial lesion lasts between 24 and 48 hours, although the eruption itself may last longer because of recurrent crops of lesions. The urticarial lesions can be found anywhere on the body.

A history of allergy to food or medication, outdoor exposure, or a recent insect bite may be reported in hypersensitivity reactions. Generalised swelling and airway compromise, hypotension, and tachycardia may be present.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Hypersensitivity rash due to penicillinCDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Scarlet fever

Approximately 90% of scarlet fever cases occur in children under 10 years old.[76]

It is usually a mild illness, but is highly infectious.

Presents with a generalised, erythematous rash, which feels like sandpaper and is often preceded by a sore throat (pharyngitis, tonsillitis).

Pharyngeal erythema with exudates, palatal petechiae, and a red, swollen (strawberry) tongue are suggestive features.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: The scarlet fever rash first appears as tiny red bumps on the chest and abdomen that may spread all over the body; looking like sunburn, the skin feels like a rough piece of sandpaper and rash lasts about 2 to 5 daysCDC Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

SSSS

A generalised erythematous rash with skin exfoliation may suggest SSSS. Fragile bullae may also be seen on the skin surface, and a positive Nikolsky's sign (blister induced with lateral pressure) may be observed. Superficial desquamation/exfoliation occurs in 2 to 5 days, leaving denuded and crusted underlying skin.

A history of recent infection of the skin, respiratory tract, mouth, or gastrointestinal tract may be reported. Young children (age <6 years) are most commonly affected, although SSSS may present in older children with underlying renal insufficiency. A prodrome of fever, malaise, and tender skin before onset of rash may be reported.

TSS

A diffuse, erythematous rash on the trunk, palms, and soles of feet with oedema is seen. Cutaneous desquamation may develop 1 to 2 weeks after onset, starting on the palms and soles. A history of recent surgery or super-absorbent tampon use in adolescent females may be reported. Hyperaemic oral mucosa is seen. Signs of systemic upset are common. These include high fever, hypotension, headache, confusion, malaise, pharyngitis, diarrhoea, vomiting, and respiratory distress. Diagnosis of TSS is made clinically in the presence of fever and hypotension.

SJS/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) disease spectrum

Targetoid lesions (annular erythematous rings with an outer erythematous zone and no central blistering sandwiching a zone of normal skin tone) may be the initial features.

Rheumatic fever

Erythema marginatum (a fleeting pink rash typically involving the trunk and proximal extremities) is seen. Subcutaneous nodules, which are typically firm and painless, may also be present. A recent history of sore throat, prolonged fever, migratory large joint tenderness, chest pain, and dyspnoea may be reported; a history of involuntary movements (Sydenham chorea) may also be obtained. A cardiac murmur or pericardial rub may be detected.

Juvenile arthritis

A transient erythematous non-pruritic rash, favouring the trunk and sites of pressure, is seen. Periodic fevers (often in the late afternoon, spiking in the evening, and resolving), joint pain, and myalgia may be reported.

SLE

A malar butterfly rash suggests SLE, but a discoid or photosensitive rash may also be seen. Fever, fatigue, recurrent infection, arthralgias, malaise, and chest pain may be reported. Arthritis and serositis (pleuritis or pericarditis), hypertension, oedema, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or lymphadenopathy may be present on examination.

Sarcoidosis

Erythema nodosum (tender erythematous nodules on the lower extremities) may be seen. Other cutaneous signs may include multiple scattered papules (most commonly on the face but may affect any site) or larger plaques (often multiple with a symmetrical distribution). Lupus pernio, although less common (with a predilection for black females), is a characteristic cutaneous feature of sarcoidosis and presents as indurated plaques with discoloration of the nose, cheeks, lips, and ears.

Patients may report systemic symptoms such as cough, fatigue, arthralgias, wheezing, photophobia, red eye, blurred vision, weight loss, and headache. Weight loss, lymphadenopathy, and uveitis may be seen.

Lyme disease

A characteristic annular lesion with scale (erythema migrans) is the most common initial manifestation. A history of exposure in a tick-endemic area (includes parts of North America, Europe, UK, and Asia) may be reported, and typically the rash develops 1 to 4 weeks after exposure.[39] Symptoms may include fever and sweats, swollen glands, headache, myalgias, fatigue, arthralgia, and cognitive impairment (sometimes described as 'brain fog'). Meningismus, neuropathy, and evidence of carditis or myopericarditis may also be present.[39][96][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Erythema migrans in Lyme diseaseCourtesy of Christian Speil, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Springfield, IL [Citation ends].

Maculopapular rash

Possible diagnoses include initial rash in meningococcal disease, infective endocarditis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), Kawasaki disease, measles (rubeola), HIV seroconversion, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), and Dengue fever.[1][89]

Meningococcal disease

A generalised macular rash may be the initial presenting feature of meningococcal disease, although this progresses to a more purpuric rash. Although most cases of meningococcal disease are sporadic, a history of contact with an infected person may be reported. Immunocompromise (e.g., secondary to asplenia or HIV infection) is a predisposing factor for meningococcal disease. Fever, malaise, and nuchal rigidity are generally present. Signs of sepsis such as cold hands and feet, pallor or mottled skin, drowsiness, and respiratory distress may also be seen.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Petechial rash in invasive meningococcal diseaseThomas AE, et al. BMJ. 2016 Mar 22;352:i1285 [Citation ends].

Infective endocarditis

Painless maculopapular lesions on palms and soles (Janeway lesions) may be seen. The patient may have a history of congenital heart disease or a recent procedure (e.g., indwelling vascular catheter, dental treatment).[51] Presenting symptoms may include fever, malaise, or evidence of septic emboli (e.g., stroke). Examination findings include Osler nodes (painful nodules on tips of fingers), Roth spots (haemorrhagic retinal lesions), and a heart murmur.[52]

DRESS

A morbilliform (measles-like) eruption, initially involving the face, upper trunk, and upper extremities, with later involvement of lower extremities may suggest DRESS. Patients may have a recent history of anticonvulsants and sulfonamide use. Other drugs (including lamotrigine, allopurinol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], captopril, calcium-channel blockers, mexiletine, fluoxetine, dapsone, terbinafine, metronidazole, minocycline, and antiretroviral drugs) have been implicated. The time interval between intake of the offending medication and symptoms is usually 2 to 6 weeks.

Fever, lymphadenopathy, and clinical features of severe visceral involvement (e.g., right upper quadrant tenderness/hepatomegaly with hepatitis, crackles/wheezes/tachypnoea with pneumonitis) may be seen. The diagnosis is made if the following criteria are met: drug-induced generalised eruption; associated systemic involvement (lymph node or visceral); and presence of eosinophilia (eosinophil count ≥1.5 x 10⁹/L [≥1500/microlitre] and/or circulating atypical lymphocytes).

Kawasaki disease

A polymorphous maculopapular rash on the trunk may be seen. The rash is typically generalised and exanthematous without petechiae. In the febrile phase, perineal erythema and desquamation may be noted.[89] It typically affects children aged <5 years, with a seasonal bias (winter to late spring). Patients may report a fever lasting ≥4 days.[89][90]

Conjunctival injection, cervical lymphadenopathy, and oropharyngeal changes (including hyperaemia, oral fissures, and strawberry tongue) may be seen.

Diagnosis is made clinically, as no specific diagnostic test is available.

Recognising Kawasaki disease is critical due to the possibly life-threatening complications if untreated (e.g., myocarditis, coronary artery dilation). An echocardiogram should be obtained in all patients to evaluate cardiac status and to assess for the presence of coronary artery abnormality.[89][90]

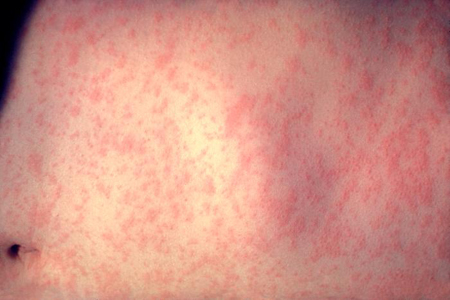

Measles (rubeola)

Erythematous macules and papules beginning on the face and behind the ears may be seen.[97] Spread is cephalocaudal; the rash lasts about 3-7 days and then begins to fade.[97] The child may be unimmunised or immunodeficient with a history of exposure to an infected person. The incubation period is 10-12 days (but can vary from 7-21 days).[97][98] Symptoms may include a prodrome of cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis that lasts about 5 days. Koplik spots (grey-white papules on the buccal mucosa/soft palate) appear during the prodrome and have long been considered pathognomonic of measles. However, in one cohort study Koplik spots were also associated with other viral infections (e.g., rubella, parvovirus, and human herpesvirus 6).[99][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Child with measles showing the characteristic red blotchy rash on his buttocks and back during the third day of the rashCDC [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Koplik spotsCDC [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Koplik spotsCDC [Citation ends].

HIV infection

A fine morbilliform eruption on trunk and upper arms, and occasionally palms and soles, may be a sign of recent HIV infection. Typically, this lasts for 4 to 5 days and resolves spontaneously. HIV seroconversion develops as an acute syndrome 3 to 6 weeks after exposure. Patients may report fatigue, malaise, headache, and myalgia.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

A macular eruption on the wrists, ankles, palms, and soles, spreading centrally, and generally sparing the face, is a feature of RMSF secondary to a tick bite. This may become petechial as the rash progresses. Intense inflammation or ecchymoses may be present at the site of the tick bite.

Outdoor activities and possible exposure in tick-endemic areas may be reported. Most cases of RMSF are from the US states of Arkansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee; cases have also been confirmed in Canada, Mexico, and Central and South America.[100]

Actual antecedent tick bite or tick attachment is made in 45% to 60% of patients. Many patients will develop an influenza-like syndrome (with headache, confusion, malaise, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea) about 1 week after exposure. A rash develops in 90% of patients but is only rarely present in the first 3 days of illness. Conjunctivitis, altered mental status, lymphadenopathy, peripheral oedema, and hepatomegaly may be present. Seizures are uncommon.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Maculopapular and petechial rash of Rocky Mountain spotted feverFrom the collection of Dr Christopher A. Ohl [Citation ends].

Dengue fever

Dengue virus is transmitted by female mosquitoes mainly of the species Aedes aegypti.

The virus is endemic in 128 countries, including countries in the Southeast Asian and Western Pacific regions, the Caribbean, Latin America, and some regions in the US, Africa, and the Middle East. In 2016, large outbreaks were reported worldwide. The number of dengue cases reported to WHO has increased over 8-fold over the last two decades, from 505,430 cases in 2000, to over 2.4 million in 2010, and 5.2 million in 2019.[94]

Approximately 90% of cases of dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) are in children under 5 years of age.[101]

A diagnosis of dengue fever should be suspected in any patients residing in countries where dengue infection is endemic, or travelling from such areas within the past 2 weeks. Clinical features range from mild fever with maculopapular rash, to life-threatening plasma leakage, respiratory distress, organ impairment, and bleeding.[1]

After the incubation period (4-10 days), the onset of symptoms is usually abrupt. Fever is characteristic of infection with very high spikes of 39.4°C to 40.5°C (103°F to 105°F). The fever generally lasts 5 to 7 days, and may cause febrile seizures or delirium in young children.

Other clinical features vary according to the age of the patient. Infants and young children have undifferentiated fever and a maculopapular rash.[1] Older children may have mild fever and maculopapular rash, or severe disease with high fever (usually biphasic), severe headache, retro-orbital pain, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, and petechiae.

Diffuse skin flushing of the face, neck, and chest develops early on in the infection. This evolves into a maculopapular rash involving the whole body, usually on the third or fourth day of the fever. The flushing may blanch when the affected skin is pressed.[102] The rash fades with time and appears as islands of pallid areas during the convalescent phase.

Severe dengue is a potentially deadly complication due to plasma leaking, fluid accumulation, respiratory distress, severe bleeding, or organ impairment. Symptoms include abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, tachypnoea, ascites, pleural effusion, and postural dizziness. These usually develop 3 to 7 days after the first symptoms of the virus after defervescence.[94] Patients may have fine petechiae scattered on the extremities, axillae, face, and soft palate, usually seen in the febrile period.[11] More significant haemorrhage can manifest as epistaxis, gingival bleeding, haematemesis, melaena, or bleeding from a venipuncture site.[95]

Vesiculobullous rash

A vesiculobullous rash in a systemically unwell child should prompt consideration of SJS/TEN. This is a spectrum of epidermal necrosis with designation dependent on the extent of involvement of body surface area.

In SJS, <10% of body surface area is affected (typically the palms, soles, and extensor surfaces). In TEN, >30% of the skin surface is involved, with widespread cutaneous involvement. If 10% to 30% involvement is noted, an SJS/TEN overlap is diagnosed.[47] Skin lesions are initially targetoid and often become confluent. Bullous lesions develop, and a positive Nikolsky's sign (blister induced with lateral pressure) may be seen in involved areas.

A recent medication history (e.g., anticonvulsants, sulfonamides, NSAIDs, allopurinol, antihelminthics, antimalarials, chlormezanone, corticosteroids, AIDS medications such as nevirapine, selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors, and lamotrigine) may be reported.[103] Other historical aspects include recent upper respiratory tract infection, infection with mycoplasma, or viral infection (e.g., herpes, EBV, or CMV).

Pain is prominent. Mucosal surfaces (oral, conjunctival, anogenital) are also affected, with erosive lesions. Most patients appear acutely unwell, and evidence of secondary infection may be seen.

Petechial/purpuric rash

Possible diagnoses include established meningococcal septicaemia, leukaemia, immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura), and later stages of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[38][104]

Meningococcal disease

A generalised petechial or purpuric rash may be the presenting feature of meningococcal septicaemia.[48] Typically, it is said to be non-blanching under pressure, which can be tested with a glass microscopic slide.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Petechial rash in invasive meningococcal diseaseThomas AE, et al. BMJ. 2016 Mar 22;352:i1285 [Citation ends].

Leukaemia

Ecchymoses or petechiae as a consequence of thrombocytopenia may be a presenting feature. Acute lymphocytic leukaemia is the most common type in children. Symptoms of underlying cytopenias (e.g., fever, chills, fatigue, weakness, infection, anorexia, night sweats, shortness of breath, bony tenderness, epistaxis, bruising, or bleeding gums) may be present. Fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, pallor, and bleeding/swollen gums may be seen.

IgA vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura)

Classic presentation is a tetrad of petechial or purpuric lesions (typically on lower extremities), abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, and IgA nephropathy.[86][87] A recent history of upper respiratory infection may be present.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Palpable purpura on the lower extremities of a child with immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura)Courtesy of Paul F. Roberts, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura): purpura mainly affects the legs, up to the gluteal muscles, inflaming the joints of the ankle and knee, but can also affect the arms and elbowFrom Wikimedia Commons [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura): purpura mainly affects the legs, up to the gluteal muscles, inflaming the joints of the ankle and knee, but can also affect the arms and elbowFrom Wikimedia Commons [Citation ends].

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

A petechial rash may present in the later cutaneous manifestations.

Investigations

In patients with widespread urticaria, skin prick testing or a radioallergosorbent test should be considered.[105]

FBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, biochemical studies, and urinalysis may be helpful in the diagnosis of systemic illness. These include meningococcal disease, DRESS, Kawasaki disease, SLE, IgA vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura), and juvenile arthritis. FBC with differential, peripheral smear, and bone marrow biopsy should be considered if leukaemia is suspected.

Serological investigations may include rapid strep test (pharyngeal swab), polymerase chain reaction or throat culture to confirm scarlet fever; enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or immunofluorescence assay, and IgM and IgG immunoblot (Western blot) assays in suspected Lyme disease; indirect immunofluorescent antibody serology and convalescent serology in Rocky Mountain spotted fever; rapid strep test and streptococcal antibody titre if rheumatic fever is suspected; ELISA for Staphylococcus aureus toxin in SSSS; and rheumatoid factor in suspected juvenile arthritis. Assays for HIV infection should be considered.

Blood cultures should be ordered if meningococcal disease, TSS, infective endocarditis, or SJS/TEN is suspected.[52]

Lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be ordered if meningococcal disease is suspected and if it is safe to do so.[75]

Echocardiography should be ordered if rheumatic fever, infective endocarditis, or Kawasaki disease is suspected.[52][89][90]

A chest x-ray should be ordered if rheumatic fever or sarcoidosis is suspected.

Skin biopsy may be considered in SSSS, SJS/TEN, DRESS, and IgA vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura). Skin or lymph node biopsy may be useful in confirming sarcoidosis.

Patch testing is useful for predicting and diagnosing some types of hypersensitivity reactions (e.g., some delayed drug eruptions).[106] Pre-treatment human leukocyte antigen screening may be of benefit in select populations.[107]

Positive in vitro drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation tests and leukocyte migration tests may confirm the diagnosis of TEN/SJS. Drug provocation studies may also confirm or rule out a causative medication but should be done under monitored conditions to avoid anaphylaxis. Oral rechallenge with a suspected causative medication is not generally recommended following a severe drug eruption.[108]

Well child: mild systemic involvement

Erythematous rash

Possible diagnoses include erythema multiforme, roseola infantum (sixth disease), and erythema infectiosum (fifth disease).

Erythema multiforme

Target lesions (annular erythematous rings with an outer erythematous zone and central blistering sandwiching a zone of normal skin tone) with symmetrical distribution on the extremities may be seen in erythema multiforme, a self-limiting generalised exfoliative dermatitis. It is often considered a milder variant of the SJS/TEN spectrum. Presentation is rapid and lesions are painful. Atypical targetoid papules (no central blistering) may also be present. Oral/genital mucosal erosions may be seen.

A recent medication history of sulfonamides, penicillin, antimalarials, or anticonvulsants, or a history of recent infection with mycoplasma, herpes, EBV, or CMV may be reported.

Roseola infantum (sixth disease)

A generalised rose-pink rash on the trunk and proximal extremities is seen. Red papules and erosions at the soft palate and uvula (Nagayama spots) are characteristic. A high fever for 3 to 5 days (with the appearance of rash during defervescence), mild upper respiratory symptoms, and seizures may be reported. Cervical or occipital lymphadenopathy may be present. Occasionally, encephalopathy and aseptic meningitis develop.

Erythema infectiosum (fifth disease)

A bright facial erythema (slapped cheeks) sparing the nose and perioral area is characteristic. This is followed in 1 to 4 days by a lacy rash on the extremities, which may last for a few weeks. A history of exposure to an infected person may be given. Erythema infectiosum is particularly seen in children aged 4 to 10 years during the winter and spring. Patients may report a mild prodrome, and joint pain is not uncommon. On examination, tenderness of the hands, wrists, ankles, and feet may be seen.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Typical erythematous slapped cheeks of erythema infectiosumCourtesy of Gary A. Dyer [Citation ends].

Maculopapular rash

Possible diagnoses include a simple drug reaction, CMV, EBV, or rubella infection, and Mpox.

Simple drug reaction

A pruritic maculopapular eruption on the trunk and extremities may be seen. In patients undergoing chemotherapy, a maculopapular rash characterised by monomorphic erythematous papules may be seen. A drug reaction should be suspected when a rash presents within 4 to 12 days of beginning a new medication.[40] Antibiotics and anticonvulsants are most commonly implicated in cutaneous drug reactions, although other drugs and herbal/nutritional products may also be responsible. Patients may have a history of medication allergy. Systemic upset is variable in simple drug reactions.

CMV infection

A maculopapular rash, with petechiae commonly present, is seen. In healthy people, CMV infection is often asymptomatic or manifests as an infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome, where pharyngitis, fever, malaise, and headache may be noted.

Lymphadenopathy (cervical, submandibular, or generalised) and hepatosplenomegaly are common. Signs of sepsis may be seen in severe CMV disease: for example, in immunocompromised patients.

EBV infection

In approximately 35% of patients, a maculopapular eruption begins on day 4 to 6 of illness, initially on the trunk and upper extremities, then extending to the forearms and face, with some areas becoming confluent. In most patients receiving antibiotic therapy (ampicillin or amoxicillin) a generalised copper-coloured eruption is induced. This rash usually occurs 1 week after taking the medication and lasts about 1 week before resolving, with desquamation.

Symptoms and signs of clinical EBV infection include pharyngitis, fever, lymphadenopathy (cervical, submandibular, or generalised), and hepatosplenomegaly. Genital ulcerations may be present.

Rubella infection

A characteristic eruption of rose-pink macules is seen. This begins on the face and extends cephalocaudally, lasting 2 to 3 days before fading in the same order. The typical progression is more helpful in suspecting this diagnosis than is the apparently rather non-specific eruption.

Rubella is responsible for a mild, self-limiting illness in children. Clinical disease is more common in unimmunised or immunodeficient patients. After a 16- to 18-day incubation period a prodrome develops, including fever, headache, and upper respiratory symptoms. Joint pain is common. Petechial macules on the soft palate (Forschheimer spots) are characteristic of rubella infection. Tender cervical lymphadenopathy is common, and joint tenderness may be seen.

Mpox

Presents with a characteristic rash that progresses in sequential stages from macules, to papules, vesicles, and pustules.[24][25] The rash typically moves from the facial area distally to the extremities; however, observations from the 2022 outbreak describe lesion(s) commencing in the genital area, which may be few and at different stages of development (often with only a single lesion observed) and a predisposition for rash to occur without a prodromal phase.[21]

Symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, headache, backache, and myalgia may appear before or after the rash, or not at all.[109]

Anorectal symptoms (e.g., severe/intense anorectal pain, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, or purulent or bloody stools, associated with perianal/rectal lesions and proctitis, pruritus, dyschezia, burning, swelling, and mucus discharge) have been unique to the 2022 global outbreak, and were not described previously.[110][111]

Vesiculobullous rash

Possible diagnoses include varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), hand-foot-and-mouth disease, congenital syphilis, gonorrhoea infection, bullous impetigo, and Mpox.[1][21][49][50]

Varicella-zoster infection

A generalised pruritic, vesicular rash on an erythematous base, often referred to as 'dew drops on rose petals', is seen in chickenpox. Successive crops of lesions appear over several days on the trunk, face, and oral mucosa; typically, lesions are in different stages of evolution, from vesicles to crust, and do not scar. Haemorrhagic and bullous lesions rarely occur.

The clinical presentation of varicella zoster virus infection may be indistinguishable from that of Mpox and co-infection may occur.[112][113][114]

An exposure history to a person with chickenpox should prompt suspicion.

Systemic symptoms include low-grade fever, malaise, and headache.[1]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Varicella lesions in young boyCDC/J.D. Millar and the Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease

A vesicular rash on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and the buttocks, with or without petechiae, is seen. This is more common in summer and autumn.

Symptoms include low-grade fever, loss of appetite, sore throat, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and general malaise. Oral erosions and conjunctival haemorrhage may be seen.

Syphilis

Acrally located vesicles and bullae (which may be haemorrhagic) may be seen in congenital syphilis. Early congenital syphilis refers to signs or symptoms that appear in the first 2 years of age. Late congenital syphilis is when clinical disease develops after 2 years of age.[115] Secondary-stage lesions generally appear 4 to 10 weeks after the initial appearance of primary lesions.[49] These manifest primarily as painless, coin-like macular lesions on flanks, shoulders, arms, chest, back, hands, and soles of feet, typically reddish-brown, and 3 mm to 10 mm in size.

In congenital syphilis, a maternal history of secondary or tertiary syphilis may be reported. The neonate develops lesions within the first 2 weeks of life subsequent to transplacental transmission.

A history of sexual activity may be reported in an older child or adolescent.

Patients present with a variety of symptoms, such as malaise, sore throat, headache, weight loss, low-grade fever, pruritus, and muscle aches, in addition to dermatological manifestations. Patchy (moth-eaten) alopecia, genital lesions (condylomata lata), and superficial mucosal erosions (mucous patches) may be seen.[49]

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: This newborn presented with symptoms of congenital syphilis that included lesions on the soles of both feetCDC: PHIL image ID 4148 [Citation ends].

Gonorrhoea

Skin papules that progress into haemorrhagic pustules may be seen. Bullae, petechiae, or necrotic lesions on the extremities may also be present.[50]

Patients may report a history of sexual activity. Symptoms include dysuria, vaginal or penile discharge, and joint pain. On examination, joint tenderness (polyarthritis) and conjunctivitis may be noted.[50]

Mpox

Presents with a characteristic rash that progresses in sequential stages (from macules, to papules, vesicles, and pustules) at the same stage of development.[24] The rash typically moves from the facial area distally to the extremities; however, observations from the 2022 outbreak describe lesion(s) commencing in the genital area, which may be few and at different stages of development (often with only a single lesion observed) and a predisposition for rash to occur without a prodromal phase.[21]

Symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, headache, backache, and myalgia may appear before or after the rash, or not at all.[109]

The clinical presentation of Mpox may be indistinguishable from that of varicella zoster virus infection and co-infection may occur.[112][113][114]

Anorectal symptoms (e.g., severe/intense anorectal pain, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, or purulent or bloody stools, associated with perianal/rectal lesions and proctitis, pruritus, dyschezia, burning, swelling, and mucus discharge) have been unique to the 2022 global outbreak, and were not described previously.[110][111]

Petechial/purpuric rash or bruising

Possible diagnoses include immune thrombocytopenia and child abuse.

Immune thrombocytopenia

Children with immune thrombocytopenia typically present with a purpuric rash on the skin and buccal mucosa. However, some may present with significant coagulopathy and report a rapid onset of bleeding.

Patients may report a recent viral infection or immunisation.

Child abuse

Various cutaneous findings (bruises, finger marks, burns, scratches, scalds) may be present, and other signs of neglect and/or poor growth may be seen. An inconsistent/incongruent history from a parent/carer (e.g., fractures in a non-mobile child), frequent hospital visits and injuries, delay in presentation to healthcare practitioner, and recurrent trauma episodes without adequate explanation may all be reported. Other features include a suspicious pattern of injury (metaphyseal 'bucket handle' fractures, posterior rib fractures, spiral fractures, unexpected old fractures), guarding or reduced range of movement, palpable callus in healing fractures (shin bruises, knee grazes), and antalgic gait or limp. The child may seem inconsolable in the presence of parents.

Investigations

For many viral exanthems, diagnosis is clinical, and tests are not routinely recommended. Serological investigations may be helpful to confirm roseola infantum (sixth disease), erythema infectiosum (fifth disease, caused by parvovirus B19 infection), CMV or EBV infection, rubella, chickenpox, and hand-foot-and-mouth disease. In patients with suspected mpox infection, polymerase chain reaction testing should be conducted as soon as possible.[22]

In patients with suspected syphilis or gonorrhoea infection, a range of specific studies should be ordered. This may include serology, molecular studies, and lesional fluid culture and microscopy.[49][50]

FBC and coagulation studies should be ordered if immune thrombocytopenia or child abuse are suspected.

Skeletal radiographs of suspicious areas should be ordered in suspected child abuse.

Skin biopsy may be considered if erythema multiforme and syphilis are suspected.

Well child: no systemic involvement

Erythematous patches and plaques

Possible diagnoses include psoriasis and pityriasis rosea.

Psoriasis

Lesions are red, inflamed, silvery-white scaly, and circumscribed papules and plaques on elbows, knees, extensor limbs, and scalp. Psoriatic nails have a pitted surface and/or hypertrophic (subungual) changes. Childhood psoriasis has a variable course and seldom completely subsides. Severity is aggravated by genetic, infectious, emotional, and environmental factors. The diagnosis is usually clinical.[116]

Pityriasis rosea

A characteristic herald patch (a 2- to 5-cm oval-shaped lesion with superficial scale, sometimes with a collarette of scale) may be present. However, within a few days, crops of smaller lesions may be noted. Lesions are most apparent on the trunk and proximal extremities, arranged along the skin lines to form a 'fir tree' pattern on the back or a 'school of minnows' pattern on the flank. Patients may report a recent upper respiratory infection. Other symptoms include fever, malaise, headache, and arthralgia.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Herald patchCourtesy of Patricia Treadwell, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis [Citation ends].

Eczematous rash

Possible diagnoses include irritant contact dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Irritant dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis

This is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction that results in localised burning, stinging, itching, blistering, redness, and swelling at the area of contact with the allergen. The eruption (erythematous scaly papules or patches) is often clearly delineated with sharp borders and confined to the areas where the allergen has come into contact with the skin.

May be a history of recent exposure to Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac) or nickel, a previous history of allergy to these agents, or previous dermatitis in response to an agent.

Other allergic conditions may be triggered by exposure to an allergen, such as allergic rhinitis, asthma, and anaphylaxis.

Atopic dermatitis

Scaling red patches or papules on the face or extensor surfaces are a feature. Pruritus is intense. Xerosis and excoriations are typically evident, and areas of hypo/hyperpigmentation may be seen.

A history of hay fever, atopic asthma, or milk allergy or a family history of atopic diseases may be obtained. Patients may also report recurrent dermatitis in areas of exposure to potential allergens (e.g., skincare products, or wool and lipid solvents).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Acute atopic dermatitis in the antecubital fossa of a 9-year-old girlCourtesy of Christina M. Gelbard, University of Texas, Houston, TX [Citation ends].

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

This presents in infants (typically <2 months of age) as a thick scale on the scalp, or 'cradle cap'. It may also involve the nappy area. In older children, the perinasal areas, eyebrows, glabella, and scalp may be involved. Lesions are non-pruritic.

Maculopapular rash

Possible diagnoses include tinea corporis, scabies, second stage of syphilis, impetigo, folliculitis, mastocytosis, erythema toxicum neonatorum, and Mpox.

Tinea corporis

Annular, scaly lesions with central clearing, slightly elevated reddened edge, and abrupt transition from abnormal to normal skin are characteristic. Exposed areas are the most common location for lesions, but any area of the body can be affected. It typically presents as single or multiple lesions on the trunk, extremities, or face. Pruritus may also be a feature.

A history of contact with an infected person or animal, or skin contact with a fomite carrying the organisms, may be reported.

Scabies

Eczematous papules and patches, typically involving interdigital spaces, umbilicus, groin, and axillae are a feature (although lesions can appear anywhere). Some lesions may become nodular, and urticarial lesions may be noted. Characteristic burrows may be seen (intact tunnel with a tiny dark dot, the mite, at the end), typically in the interdigital web spaces. An intense pruritus, especially at night, is characteristic.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Maculopapular inflammatory rash on the abdomen due to scabies. Of importance, is how this rash appears to resemble many other breakouts, including measles and chickenpoxCDC/Joe Miller [Citation ends].

Impetigo

An erythematous papule is evident, which then becomes a unilocular vesicle. The vesicle ruptures, and eventually becomes a yellow-golden crust. An exposure history to an infected person is common. Patients may have a pre-existing skin condition (e.g., atopic dermatitis, scabies); if so, the disease process usually starts in an existing lesion or in a traumatised area.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Facial impetigoCourtesy of Michael Freeman, Bond University, Queensland, Australia [Citation ends].

Folliculitis

Multiple small papules and pustules on an erythematous base, on any hair-bearing site, may be seen. Deeper infection may result in follicle-centred dermal abscesses. These usually resolve spontaneously. In infants, a specific form, eosinophilic pustular folliculitis, may be seen. This presents as pustules and vesicles primarily involving the scalp; lesions often have an erythematous base and crusting.

Bacterial folliculitis may present in children with immunosuppression (e.g., diabetes mellitus). Exposure to contaminated water (e.g., in a hot tub) is recognised as a common cause of Pseudomonas folliculitis. There may be a history of skin trauma.

Mastocytosis

Solitary or widespread papular lesions (5-15 mm; yellow-brown to yellow-red) are seen. Lesions may periodically blister and then return to their original form. Urticaria may be also seen; if it is present, a surrounding erythematous flare may be observed when the lesion is rubbed (Darier sign).

Erythema toxicum neonatorum

Mpox

Presents with a characteristic rash that progresses in sequential stages (from macules, to papules, vesicles, and pustules) at the same stage of development.[24] The rash typically moves from the facial area distally to the extremities; however, observations from the 2022 outbreak describe lesion(s) commencing in the genital area, which may be few and at different stages of development (often with only a single lesion observed) and a predisposition for rash to occur without a prodromal phase.[21]

Vesicular rash

Miliaria crystallina

1- to 2-mm vesicles on the face, neck, and trunk of a well neonate.

Caused by blockage of immature sweat ducts, causing sweat retention in the skin.[118]

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis

More common in dark-coloured skin.

Usually present at birth or in first few days of life.

Superficial sterile pustules.

Later, development of hyperpigmented macules - some with a white collarette.

Affects forehead, chin, neck, and shins. May also be seen on the palms and soles.[118]

Investigations

For many aetiologies diagnosis is clinical; confirmatory tests are not usually necessary.

In suspected infectious aetiologies, bacteriology (e.g., Gram stain and/or culture of lesional fluid) may be prudent when the diagnosis is in doubt or if the patient does not respond to appropriate empirical therapy.

Serum IgE levels, skin prick testing, and patch testing may be helpful in confirming a cause of allergic contact or atopic dermatitis.[119]

Skin biopsy may be considered if a diagnosis of psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, or mastocytosis are considered.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer