Aetiology

The primary differential diagnoses to consider for any rash presenting in childhood are viral exanthems, inflammatory dermatoses, local bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections, tick-borne disease, drug eruptions, systemic bacterial infections, anaphylactic reactions, haematological disorders, and vasculitic and rheumatological conditions.

Viral infections

A viral exanthem is a skin eruption occurring as a symptom of a viral illness. Many of these eruptions are non-specific and may precede, occur simultaneously with, or follow a viral illness. However, specific viral aetiologies are recognised as causing a rash in children.[1] These include:

Varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox): predominantly affects children; almost all cases occur in children aged <10 years, although this infection occurs much less frequently in areas where vaccination is routine.[1][2]

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection: approximately 15% to 35% of people with EBV will have a cutaneous eruption. Concomitant ingestion of ampicillin or amoxicillin increases the incidence of eruption.[3]

Roseola infantum (sixth disease): caused by human herpesvirus types 6 and 7 and common in infancy and early childhood.

Erythema infectiosum (fifth disease): caused by parvovirus B19, and most common in winter and spring.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease: an enterovirus illness (most typically coxsackie virus type A16 or enterovirus 71) usually presenting in the summer or autumn.[4][5][6]

Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome (PPGSS): most often reported with parvovirus B19 infection. However, it has also been noted with cytomegalovirus (CMV), coxsackie virus B6, EBV, hepatitis B virus, human herpes virus (HHV)-6, HIV, measles, and rubella virus infections.[7][8]

Rubella (German measles): caused by an RNA togavirus. This is usually responsible for a mild, self-limiting illness in children. Incidence has decreased remarkably since the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine was introduced in 1969. Clinical disease is more common in unimmunised or immunodeficient patients.

Measles (rubeola): caused by an RNA paramyxoviridae virus. The incidence of measles has decreased with routine immunisation, though outbreaks continue to occur, and atypical measles eruptions also arise in patients for whom immunisation failed or who are immunodeficient. In 2019, 1274 cases of measles were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[9] Most cases occurred in unvaccinated patients.[1][9] In 2023, a total of 58 measles cases were reported in the US; as of May 16, 2024, 139 measles cases had been reported.[9] In the UK, there were over 1000 confirmed measles cases between 1 January 2024 and 22 April 2024, compared with 54 cases and 368 cases for the whole of 2022 and 2023, respectively.[10]

Cutaneous herpes simplex: infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 or HSV-2 can cause oral, genital, and ocular ulcers. The primary episode occurs during initial infection with HSV, in which the host lacks an antibody response. Often presents in children with eczema as eczema herpeticum.

Molluscum contagiosum: caused by the molluscum contagiosum virus. Lesions are cutaneous (less commonly mucosal). They appear as pearl-like, smooth papules, which are sometimes umbilicated. Lesions are generally caused via skin-to-skin or fomite contact in children.

Cytomegalovirus infection: the primary infection is often asymptomatic, but clinical manifestations, including rash, may occur in immunocompromised patients.

Dengue fever: caused by a mosquito-borne virus in subtropical areas. Presents with abrupt-onset fever and erythematous maculopapular rash. Patients may have fine petechiae scattered on the extremities, axillae, face, and soft palate, usually seen in the febrile period.[1][11] Patients with severe dengue have petechiae, bleeding gums, peripheral oedema, severe abdominal pain, and persistent vomiting.

COVID-19: caused by SARS-CoV-2, has diverse presentations in the skin. May present as urticaria, a widespread maculopapular or a papulovesicular rash. COVID-19 also has a number of vasculopathic presentations and can present as chilblain-like acral lesions, livedo reticularis, or a vasculitic rash. Rashes usually present in the prodromal stage but chilblain-like lesions present late in disease.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Multi-system Inflammatory Disease in Children (MIS-C): in addition to the findings listed above for COVID-19 infections, there are cutaneous findings noted with MIS-C, which is a hyperinflammatory condition associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. These cutaneous findings include a maculopapular eruption, conjunctival injection, and oedema of the extremities. In contrast to Kawasaki disease, no desquamation is seen.[18][19]

HIV infection: patients with primary HIV infection may develop an acute seroconversion syndrome, which can include a maculopapular cutaneous eruption, 3 to 6 weeks after exposure. Oral and genital erythema and ulcerations may be noted.[4][20]

Mpox: formerly known as monkeypox, caused by a double-stranded DNA virus.[21] Incubation period is typically 6-13 days (range 1-21 days).[22][23] Presents with characteristic rash that progresses in sequential stages from macules, to papules, vesicles, and pustules.[24][25] The disease is endemic in West and Central Africa; however, a global outbreak was identified in May 2022.[26] Human‐to‐human transmission can occur through direct contact with skin lesions or infected skin, respiratory droplets and fomites, or through the transplacental route.[21] The rash typically moves from the facial area distally to the extremities. However, lesions commencing in the genital area (which may be few and at different stages of development, often with only a single lesion observed), and a predisposition for rash to occur without a prodromal phase, have been reported during the 2022 outbreak.[21]

Inflammatory dermatoses

Atopic dermatitis (eczema): a chronic skin condition characterised by an eczematous eruption, with itching and skin sensitivity to irritants.[27] It is one of the most common diagnoses for patients seen in paediatric dermatologists' clinics.[28]

Seborrhoeic dermatitis: occurs in two age groups: infants (beginning before age 2 months) and adolescents. Usually limited to the scalp in infants, but can be in the nappy and intertriginous areas.[29] In adolescents, sebaceous secretions alter the normal skin flora, which induces dermatitis in the affected areas.

Irritant contact dermatitis: can occur in response to a variety of agents that come into contact with the skin, e.g., urine may cause nappy dermatitis in children aged <3 years.

Allergic contact dermatitis: involves a true allergy. The patient experiences an initial exposure to an allergen and then develops an allergic reaction that can be characterised by skin manifestations. Among children presenting with allergic contact dermatitis, the most common precipitating agents are metal nickel and, if in the US, species of Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac).[30][31]

Psoriasis: a chronic autoimmune skin condition that tends to be exacerbated by stress, local trauma, infections, and some medications. In some patients an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern may be present: approximately 25% of adults with a diagnosis of psoriasis give a history of having psoriatic lesions before the age of 18 years. However, psoriasis tends to be under-diagnosed in children.[32]

Pityriasis rosea: a self-limiting papulosquamous disorder.[33] Approximately 75% of patients are aged between 10 and 35 years. It is thought that pityriasis rosea has an infectious aetiology, although a specific agent has not been elucidated.

Mastocytosis: a heterogeneous group of disorders, characterised by clonal mast cell proliferation and accumulation within various organs. In the skin, urticaria, vesicles, and bulla formation may be seen.

Local bacterial infections

Primary infections include:

Impetigo: a common, highly contagious, superficial skin infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus or group A beta-haemolytic streptococci. It can occur as a primary infection or secondary to pre-existing skin conditions such as eczema or scabies.[34] Impetigo can present in both non-bullous and bullous forms.

Folliculitis: a pyoderma located within a hair follicle, secondary to follicular occlusion by keratin, over-hydration, or infection. Bacterial causes include S aureus and Pseudomonas. Although more common in adults, bacterial folliculitis may be present in children with immunosuppression (e.g., diabetes mellitus). In infancy, a specific form, eosinophilic pustular folliculitis, may also be seen.

Fungal or parasitic infections

Common infestations in childhood include:

Tinea corporis (ringworm): a dermatophytic infection of the skin on the body caused by Trichophyton (most commonly) and Microsporum fungal species.

Tinea capitis: infection of the scalp caused by Trichophyton (most commonly) and Microsporum fungal species. Common features include patchy hair loss with varying degrees of scaling and redness in addition to occipital lymphadenopathy.[35]

Scabies: an infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei organisms.

Cutaneous candidiasis: a primary or secondary fungal infection caused by members of the genus Candida. Typically involves fold areas with an erythematous patch centrally and surrounding smaller satellite lesions, occasionally has whitish discharge centrally.[36][37] Often seen in the nappy area in young children.

Tick-borne infections

Infections transmitted by animal ticks (e.g., Ixodes scapularis or Dermacentor variabilis) may present with characteristic cutaneous findings. These include:

Drug reactions

Most exanthematous eruptions are believed to be delayed-type (type IV) cell-mediated (often T-cell) reactions to drug or metabolite.[40]

Antibiotics (sulfonamides, aminopenicillins, cephalosporins) and anticonvulsants are commonly associated with these eruptions. Inhibitors of programmed cell death-1 receptors (e.g., pembrolizumab, nivolumab), or nutritional or herbal supplements, may also be implicated in exanthematous eruptions.[41][42]

More significant adverse drug reactions may present with widespread mucocutaneous involvement. These include Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis, erythema multiforme, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS).[43][44][45][46]

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) constitute a spectrum of severe generalised exfoliative dermatitis.[43] SJS involves <10% of the body surface area. TEN involves >30% of body surface area, and 10% to 30% represents the SJS-TEN overlap.[47] SJS has a lower associated mortality (SJS: 1% to 5%; TEN: 25% to 35%).[43]

Common medicines causing TEN/SJS include:

Anticonvulsants

Sulfonamides

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Allopurinol.

In TEN/SJS, there is widespread cutaneous involvement, with associated involvement of ≥2 mucosal surfaces (oral, conjunctival, anogenital). Skin lesions may be initially targetoid (with no central blistering), although they often become confluent. Bullous lesions may also develop, and Nikolsky's sign (blister induced with lateral pressure) is noted within affected areas.[43] The lesions are painful and the patient appears acutely unwell. Secondary infection may occur.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stevens-Johnson syndrome: targetoid lesions and epidermal lossFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Kowal-Vern [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stevens-Johnson syndrome: epidermal loss on soles of feetFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Kowal-Vern [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Stevens-Johnson syndrome: epidermal loss on soles of feetFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Kowal-Vern [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Toxic epidermal necrolysis with epidermal loss, ocular involvement, and ecthyma gangrenosumFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Kowal-Vern [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Toxic epidermal necrolysis with epidermal loss, ocular involvement, and ecthyma gangrenosumFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Kowal-Vern [Citation ends].

The presentation of DRESS syndrome resembles a morbilliform drug eruption, but the patient is more unwell, often with fever, abdominal pain, lymphadenopathy, and facial swelling. The time interval between intake of the offending medicine and symptoms also tends to be longer, often 2 to 6 weeks. Mortality in DRESS may be 8% to 10%.[45][46] Typically, the rash starts on the face, upper torso, and upper extremities, then spreads to the lower extremities. Liver involvement is common, presenting with hepatosplenomegaly and elevated transaminases.[45]

Medications commonly associated with DRESS include:[45][46]

Sulfonamides

Anticonvulsants

Allopurinol

Minocycline.

Systemic bacterial infections

Meningococcal disease: a generalised purpuric or petechial (non-blanching) rash may be a presenting sign of meningococcal septicaemia (Neisseria meningitidis infection). A few patients may initially have non-specific erythematous macular or maculopapular lesions, typically located on the extremities.[48] Meningococcal disease classically presents with abrupt onset of fever and malaise, progressing rapidly (within 24 hours) to signs and symptoms of septicaemia and/or meningitis. Nuchal rigidity may be present.

Syphilis: caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. It is almost always transmitted by sexual contact or vertical transmission. Secondary syphilis lesions result from the haematogenous dissemination of treponemes from a syphilitic chancre. Secondary syphilis manifests primarily as mucocutaneous rash in association with vague constitutional symptoms, diffuse lymphadenopathy, and highly infectious skin lesions.[49] Lesions classically arise 6 to 10 weeks after resolution of the painless chancre of primary syphilis.[49] Oral/genital mucosal lesions are highly contagious; dry skin lesions (e.g., palm) are much less so.

Gonorrhoea infection: caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Disseminated gonococcal infection develops as a consequence of untreated primary infection. It commonly causes skin papules that progress into haemorrhagic pustules, bullae, petechiae, or necrotic lesions on the extremities.[50]

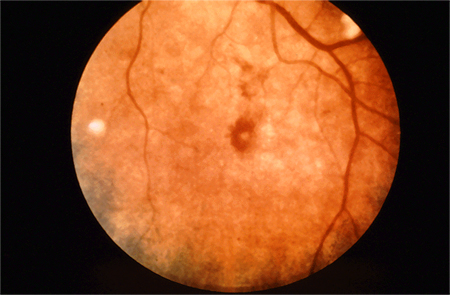

Infective endocarditis: infection involving the endocardial surface of the heart, including the valvular structures, chordae tendinae, site of septal defects, or the mural endocardium. Rare skin manifestations are Janeway lesions (painless maculopapular lesions on palms and soles) and Osler nodes (painful nodules on tips of fingers). Children with congenital heart disease have an increased risk of infective endocarditis.[51] Bacterial aetiologies include Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus bovis, Streptococcus viridans, and HACEK (Haemophilus species, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella species) organisms.[51] Fungal endocarditis is unusual in children, but can be seen in the setting of indwelling central catheters.[52] Presenting symptoms may include fever, malaise, fatigue, night sweats, or heart palpitations. Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, and Roth spots (hemorrhagic retinal lesions) are more common in subacute endocarditis.[52][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Janeway lesionsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Osler nodeFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Roth spotsFrom the collection of Sanjay Sharma, St George’s University of London, UK; used with permission [Citation ends].

Infection with mycoplasma may manifest with recurrent reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption (RIME), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS).[53]

Toxin-mediated infections include:

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS): an uncommon manifestation of infection with S aureus toxin-producing strains. Can be easily missed but, rarely, can be fatal. The toxin targets the granular layer and causes blister formation.[54] SSSS is more likely than toxic shock syndrome in children. SSSS presents with moderate fever, generalised erythema, and blisters and erosions accentuated in the intertriginous areas. The diagnosis is primarily clinical, as blood and fluid cultures are generally negative.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndromeDermpics / Science Source / Science Photo Library; reproduced with permission [Citation ends].

Scarlet fever: caused by an erythrogenic toxin produced by group A beta-haemolytic streptococci. It manifests as pharyngitis and an accompanying cutaneous eruption. The eruption appears in all areas at the same time without a particular pattern of development.

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS): TSS is an exotoxin-mediated illness caused by bacterial infection: most commonly S aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, or other group A beta-haemolytic streptococci. Caused by TSS toxin 1, staphylococcal enterotoxins, streptococcal toxins, or other toxins. Consists of a complex of symptoms, including high fever, low blood pressure, and a diffuse, erythematous rash on the trunk, palms, and soles of feet that may be desquamative. TSS is more often observed with abscesses and closed space infections, and in post-surgical patients; it may be associated with menstruation (specifically related to superabsorbent tampon use). Mortality in TSS in children is 2%.[55][Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Rash and subcutaneous oedema of the right hand due to toxic shock syndromeFrom the CDC and the Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Marked desquamation of the left palm due to toxic shock syndrome, which develops late in the diseaseFrom the CDC and the Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Marked desquamation of the left palm due to toxic shock syndrome, which develops late in the diseaseFrom the CDC and the Public Health Image Library [Citation ends].

Hypersensitivity reaction

Urticaria is a common condition characterised by the development of wheals (hives), angio-oedema, or both. Urticaria needs to be differentiated from other medical conditions where wheals, angio-oedema, or both can occur, for example anaphylaxis, auto‐inflammatory syndromes, urticarial vasculitis, mastocytosis, or hereditary angio-oedema (HAE).[56]

The cutaneous findings occur because of histamine release in the skin and increased permeability of the blood vessels. Each individual urticarial lesion lasts for 24 to 48 hours, although the eruption itself may last longer because of recurrent crops of lesions. Lesions can be found anywhere on the body. Wheals may result from an allergic reaction to a variety of agents, including foods, drugs, insect bites, stings, or infections, but often a cause for urticaria is never identified.[57]

An anaphylactic reaction is a life-threatening allergic reaction, most commonly in response to either a drug/food allergy or an insect bite/sting.[58]

Haematological disorders

A petechial rash with ecchymosis may be a presenting feature of thrombocytopenia (e.g., as a consequence of acute leukaemia or immune thrombocytopenia).

Acute lymphocytic leukaemia is the most common leukaemia in children. Clinical presentation is usually associated with signs and symptoms of underlying cytopenias. Anaemia usually presents as fatigue, dyspnoea, and dizziness; thrombocytopenia presents with bleeding, ecchymoses, or petechiae; and neutropenia presents as recurrent infections that may cause fever. Abdominal and bone pain may be present due to infiltration of blast cells in the spleen (abdominal pain) and bone marrow (bone pain). Diagnosis is based on full blood count and peripheral blood smear with confirmatory bone marrow biopsy.

Immune thrombocytopenia is a diagnosis of exclusion of alternative causes of low platelet count.[59] Children typically present with a purpuric rash but no systemic upset nor organomegaly. However, some may present with significant coagulopathy.

Vasculitic and rheumatological disease

Certain childhood vasculitic and rheumatological conditions may also present with a prominent cutaneous eruption.[60] These include:

Kawasaki disease

Juvenile arthritis

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis (formerly known as Henoch-Schonlein purpura)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Rheumatic fever

Sarcoidosis.

Most patients with rheumatic fever present with fever and a history or evidence of a recent group A streptococcal infection.[61][62] Polyarthritis, carditis, Sydenham's chorea, erythema marginatum (a fleeting pink rash typically involving trunk and proximal extremities), and subcutaneous nodules are the major manifestations.

Child abuse and self-harm

Child abuse may be difficult to identify but may present with cutaneous findings, including unexplained bruises, finger marks, burns, scratches, or scalds.[63]

Dermatitis artefacta (DA) is a skin condition caused by the actions of the patient on the skin, hair, nails, or mucosae.[64] Deliberate self‐harm differs from DA in that patients will often take responsibility for self-harm but will not acknowledge their actions in DA. Children may cut, pick, or burn their skin often in accessible areas such as the face and limbs. This is an indicator of mental health problems and/or social problems.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer