Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Recognise a sudden presentation of peptic ulcer disease to be potentially life-threatening and resuscitate according to ABC principles. Signs include:

Bleeding (haematemesis and/or melaena)

Shock

Peritonitis (if perforation has occurred).

Refer any patient who presents in the community with dyspepsia together with significant acute gastrointestinal bleeding immediately (on the same day) to a specialist.[46]

Consider peptic ulcer disease in a patient with the following symptoms and signs:

Dyspepsia, commonly related to eating and experienced at night. For more information about diagnosing dyspepsia, see Assessment of dyspepsia.

Chronic or recurrent central, upper abdominal pain or discomfort, demonstrated by the patient with the ‘pointing sign’.

Nausea, anorexia, and vomiting are uncommon, but if present, nausea may be relieved by eating.

The following risk factors increase the likelihood of peptic ulcer disease:

Helicobacter pylori infection - present in >90% of patients with duodenal ulcer and >70% with gastric ulcer[17][19]

NSAID use

Smoking

Increasing age

Personal or family history of peptic ulcer disease

An intensive care stay.

Be aware that:

Weight loss, a low haemoglobin level, or a raised platelet count associated with any one of dyspepsia, reflux, or upper abdominal pain in a patient ≥55 years may suggest malignancy and should be investigated with an endoscopy within 2 weeks[47]

Diarrhoea associated with dyspepsia may indicate Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Penetrating duodenal ulcers may cause severe pain radiating through to the back.

Endoscopy is the definitive diagnostic test for confirming peptic ulcer disease and identifying H pylori, with biopsy samples collected for rapid urease testing or histology.

Note that in practice, the rapid urease test can be falsely negative if:

There is acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding

The patient is being treated with a PPI

The patient has received antibiotics that might reduce the density of H pylori colonisation.

Request the urea breath test or stool antigen test if the patient’s H pylori status is uncertain or to re-test a patient to confirm that eradication therapy has been successful. If these are unavailable, laboratory-based serology can be used (provided its performance has been locally validated).[46]

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, H pylori infection, smoking, increasing age, personal or family history of peptic ulcer disease, and an intensive care stay are key risk factors.

A common clinical feature is dyspepsia, a chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, or discomfort centred in the upper abdomen.[49] It should be noted that most people with dyspepsia do not have peptic ulcer disease.[49]

Dyspepsia is commonly related to eating and is often nocturnal. However, the absence of epigastric pain does not rule out the diagnosis. Nausea and vomiting are uncommon; the former may be relieved by eating. Vomiting, if present, generally occurs after eating. Weight loss and anorexia may also be present.

The relief of symptoms after the use of antacids may support the diagnosis. However, this is neither a sensitive nor specific indicator.

Presentation may be sudden, with life-threatening bleeding.

Weight loss, a low haemoglobin level, or a raised platelet count associated with the above symptoms in a patient aged ≥55 years may suggest malignancy and should be investigated accordingly.[47] In particular, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (within 2 weeks) for any person aged ≥55 years who has weight loss together with any one of dyspepsia, reflux, or upper abdominal pain.[47]

If diarrhoea is also present, this may indicate Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

In patients with duodenal ulcers, the abdominal pain may be severe and radiate through to the back as a result of penetration of the ulcer posteriorly into the pancreas.

Rarely, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety indicate pyloric stenosis (a complication of peptic ulcer disease).

Importantly, peptic ulcers may cause no symptoms, especially in older people and those taking NSAIDs.

Presentation may be sudden, with:

Bleeding (haematemesis and/or melaena)

Shock

Peritonitis (if perforation has occurred).

In more typical presentations, there may be some epigastric tenderness on palpation of the abdomen, but often there are no other signs on examination. The patient can generally show the site of pain with one finger ('pointing sign').

Atypical presentations of peptic ulcer disease also occur.

Gastric and duodenal ulcers may cause occult blood loss and iron deficiency anaemia.

Rarely, a succussion splash may be heard in patients with pyloric stenosis (caused by gastric outlet obstruction).

Endoscopy

Refer any patient who presents with dyspepsia together with significant acute gastrointestinal bleeding immediately (on the same day) to a specialist.[46]

Refer for endoscopy within 2 weeks any patient aged ≥55 years who has weight loss together with any one of dyspepsia, upper abdominal pain, or reflux, to investigate possible malignancy.[47]

Endoscopy is the definitive diagnostic test for peptic ulcer disease and upper gastrointestinal tract neoplasms. Endoscopy:

Is widely available

Is more sensitive and specific for peptic ulcer disease than barium radiography

Enables biopsy (for diagnosing malignancy and for H pylori detection).

A biopsy is taken during the index endoscopy.

A rapid urease test or histology is used to identify H pylori infection.

Note that in practice, the rapid urease test can be falsely negative if:

There is acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

The patient is being treated with a PPI.

The patient has received antibiotics that might reduce the density of H pylori colonisation.

Offer any patient who has gastric ulcer and H pylori a repeat endoscopy 6 to 8 weeks after beginning treatment, depending on the size of the lesion.[46]

Consider endoscopy subsequent to treatment if the patient continues to experience symptoms.

Barium radiography should be reserved for patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo endoscopy, and it is not routinely recommended.

Anti-thrombotic treatment with either warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) or dual antiplatelet therapy is not a contraindication to endoscopy. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with or without diagnostic biopsies is regarded as a low-risk procedure for bleeding, and no or minimal alterations in the anti-thrombotic regimen are required for non-emergency diagnostic endoscopy.

For low-risk endoscopic procedures such as diagnostic endoscopy with or without biopsy, the 2021 update to the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline on endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy recommends:[50]

Continuing P2Y12 receptor antagonists as single or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)

Continuing warfarin therapy

Check international normalised ratio (INR) 1 week before endoscopy

If the INR result is within the therapeutic range then continue with the usual daily dose

If INR is above the therapeutic range but <5 then reduce the daily dose until INR returns to therapeutic range

If the INR is greater than 5 then defer the endoscopy and contact the anticoagulation clinic, or an appropriate specialist, for advice.

Omitting the morning dose of DOACs.

Biopsy and histology

Obtaining samples for urease testing (rapid urease test) and histology is invasive, and is reserved for patients in whom endoscopy is otherwise indicated. Both urease testing and histology can detect H pylori; however, histology can determine if the ulcer is neoplastic (very rarely) or if there is evidence that an NSAID is the likely cause.

Note that in practice, the rapid urease test can be falsely negative if there is acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, if the patient is being treated with a PPI, or if the patient has received antibiotics that might reduce the density of H pylori colonisation.

Urea breath test or stool antigen test for H pylori

Establish whether the patient is infected with H pylori.

H pylori infection status will normally have been confirmed during the index endoscopy for diagnosis of peptic ulcer, via biopsy samples taken for rapid urease testing or histology.

If the patient’s H pylori status is unknown or uncertain after endoscopy, the carbon-13 urea breath test or stool antigen test are the preferred investigations; if these are not available, laboratory-based serology can be used provided its performance has been locally validated.[46][48][49][51][52]

The negative predictive value of these tests is >95%. Nonetheless, if a patient with a confirmed peptic ulcer tests negative, a repeat test is warranted.[48]

Serology (antibody) testing gives less accurate results than urea breath testing or stool antigen testing and is unable to distinguish between active and historical infection.[46][53][54][55]

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), bismuth, or other medications can interfere with the performance of diagnostic tests for H pylori.

Leave a 2-week washout period after PPI use and a 4-week washout after antibiotic use before testing for H pylori with a breath test or a stool antigen test, as these drugs suppress bacteria and can lead to false negatives.[46][48]

Re-test to confirm successful eradication of H pylori using a carbon-13 urea breath test 6 to 8 weeks after starting treatment.[46]

There is insufficient evidence to recommend the stool antigen test as a test of eradication.[46]

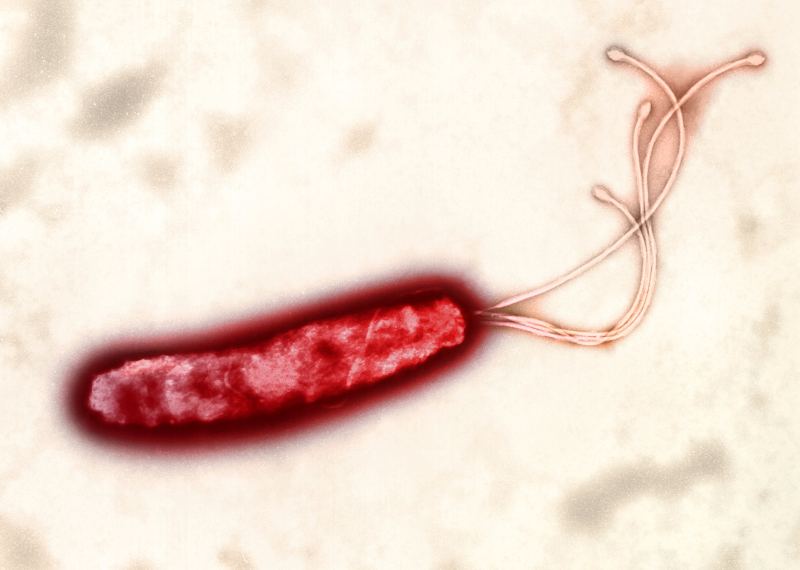

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Helicobacter pylori bacterium, transmission electron micrograph (TEM)Heather Davies/Science Photo Library [Citation ends].

Other investigations

Order a full blood count if the patient seems clinically anaemic or has evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding. A raised platelet count may indicate malignancy.

Consider Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in patients with multiple or refractory ulcers, diarrhoea, ulcers distal to the duodenum, or a family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and request a fasting serum gastrin level to look for evidence of gastrin hypersecretion. The patient should stop taking any PPI therapy prior to the test.

Also consider the possibility of surreptitious use of NSAIDs if the patient has recurrent or refractory ulcers. This can be detected via urine testing.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer