Recommendations

Key Recommendations

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding from a peptic ulcer requires urgent evaluation.

Use the Blatchford risk score at first assessment to predict the need for intervention[56][57][58][59] [ Blatchford Score for Gastrointestinal Bleeding Opens in new window ]

Transfuse any patient with massive bleeding with blood, platelets and clotting factors in line with local protocols.[56][60]

Arrange therapeutic (and diagnostic) endoscopy on the same day for patients presenting with dyspepsia and significant acute gastrointestinal bleeding.[56][59]

Prescribe proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) to patients with a bleeding ulcer who have signs of recent haemorrhage visible at endoscopy.[56][59][61]

For patients who are Helicobacter pylori negative and have peptic ulcer disease (without active bleeding):[46]

Stop non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) where possible.

Start full-dose ulcer healing therapy for 8 weeks.

For patients who are H pylori positive and have peptic ulcer disease (without active bleeding):[46]

If the patient is not a long-term user of NSAIDs:

Offer a 7-day course of H pylori eradication therapy, in line with NICE recommendations.[46]

Consider offering ulcer healing therapy with a full-dose PPI or H2 antagonist for 8 weeks.

This is standard practice in the UK based on clinical experience but bear in mind that ulcer healing therapy is not specifically recommended for this group by NICE.

If the patient is a long-term user of NSAIDs:

If the patient has a family history of gastric cancer, H pylori eradication is associated with a reduced risk of gastric cancer.[62]

Offer H pylori eradication therapy (typically a 7-day course of triple therapy).

Be aware that ulcer healing therapy and eradication therapy are sequential treatments. In practice, a specialist may advise eradication therapy before ulcer healing therapy or vice-versa based on their clinical experience and preference.

Re-test (with a urea breath test) any initially H pylori positive patient 6 to 8 weeks after beginning eradication treatment, depending on the size of the lesion.[46]

Re-treat patients who are still H pylori positive with at least one second-line eradication therapy regimen.[46][63]

Repeat endoscopy in patients with gastric ulcer and H pylori 6 to 8 weeks after beginning treatment, depending on the size of the lesion.[46]

Consider specialist referral for any patient with:[46]

Unexplained, or treatment-resistant gastro-oesophageal symptoms

H pylori that has not responded to second-line eradication therapy.

The goals of therapy are to:

Treat complications (e.g., active bleeding)

Determine and eliminate the underlying cause whenever possible - most commonly H pylori infection and/or chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Relieve symptoms

Heal ulcers.

Active gastrointestinal bleeding requires urgent evaluation with resuscitation and supportive care as appropriate.[64]

Peptic ulcer is the most common cause of life-threatening acute gastrointestinal bleeding, accounting for around 35% of cases.[56] Use the following formal risk assessment scores for any patient with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding:[56]

The Blatchford score at first assessment to predict the need for intervention[57][58][59] [ Blatchford Score for Gastrointestinal Bleeding Opens in new window ]

The full Rockall score after endoscopy to estimate the risk of rebleeding or death.[65] [ Rockall Score for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Opens in new window ]

Transfuse any patient with massive bleeding with blood, platelets, and clotting factors in line with local protocols for managing massive bleeding.[56][60]

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding recommends giving:[64]

Red blood cell transfusion if the patient’s haemoglobin is <70 g/L, with a target of 70 to 100 g/L

Platelets if the patient’s platelet count is ≤50 × 109/L.

Do not use tranexamic acid to treat patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding.[60][66][67]

Evidence from the HALT-IT trial, in which more than 12,000 patients with severe gastrointestinal bleeding were randomised to tranexamic acid or placebo, showed no improvement in outcomes but increased adverse effects for those who received tranexamic acid.[66][67] [

]

[Evidence B]

]

[Evidence B]A further systematic review and meta-analysis of extended-use high-dose tranexamic acid failed to show any improvement in mortality or bleeding outcomes.[67][68]

For further information, see:

Endoscopic management of bleeding

Following resuscitation, patients with severe acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding should undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy within 24 hours.[59][69][70][71]

Very early (less than 6 hours from presentation) endoscopy has not been associated with improved patient outcomes, and in some cases can worsen outcome.[59][69][70][71]

Most ulcer bleeding can be treated endoscopically to achieve haemostatic control.

Use one of the following methods to achieve haemostatic control of an actively bleeding ulcer:[56][59]

A mechanical method (e.g., clips) with adrenaline (epinephrine)

Fibrin or thrombin with adrenaline.

For an ulcer with a non-bleeding visible vessel use:

A mechanical method, thermal coagulation, or fibrin/thrombin as monotherapy or in combination with adrenaline.

Options for persistent refractory bleeding include:

Cap-mounted clips - have been shown to be at least as effective as other more traditional modalities (such as thermal coagulation) for primary haemostasis of peptic ulcer bleeding and are particularly useful for rescue therapy or large (>20 mm) or fibrotic ulcers, or those with a large visible vessel (>2 mm) or located in a high-risk vascular area (e. g., gastroduodenal, left gastric arteries)[59][73][74]

Haemostatic sprays for rescue therapy of uncontrolled bleeding (not for primary haemostasis due to a higher rate of rebleeding than with more definitive methods).[75][76]

Do not use adrenaline as monotherapy for the endoscopic treatment of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.[56][59][72]

After endoscopy, prescribe PPI therapy to any patient who had endoscopic evidence of recent haemorrhage.[56][59][61] Some centres use a high-dose oral PPI, but the standard approach remains an intravenous infusion for 72 hours, followed by a switch to oral administration.[61]

The role of pre-endoscopic PPI therapy in patients who present with ulcer bleeding remains an area of ongoing debate.[56][77] The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that acid-suppression drugs (i.e., PPIs or H2 antagonists) should not be offered before endoscopy because of a lack of evidence to show improved outcomes.[56] International consensus recommendations state that pre-endoscopic PPI therapy can be considered on the basis that it may downstage the lesion or reduce the need for endoscopic haemostatic treatment, although it should not delay endoscopy.[77][78]

If the patient re-bleeds after their initial endoscopy:

Repeat the endoscopy if the patient is stable and treat endoscopically or with emergency surgery.[56][61]

Offer interventional radiology if the patient is unstable.[56][61]

Patients taking anticoagulation therapy (e.g., warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs])

Consider seeking advice from an appropriate specialist if the patient is taking warfarin or a DOAC.

The BSG consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the 2021 update to the BSG and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline on endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy recommend:[64][50]

Suspending DOACs at presentation and seeking advice from a haematologist when managing patients with severe haemorrhage to weigh up the risks and benefits of the DOAC.

Suspending warfarin at presentation.

In haemodynamically unstable patients, the 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline recommends:[50]

In patients who are taking warfarin, give intravenous vitamin K and four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate. Fresh frozen plasma can be used if prothrombin complex concentrate is not available.

If the patient is taking a DOAC, consider the use of reversal agents: idarucizumab in patients taking dabigatran, and andexanet alfa in patients taking anti-factor-Xa. Intravenous four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate can be used if andexanet alfa is not available.

Note that the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends:[56]

Prothrombin complex concentrate in patients who are taking warfarin and actively bleeding

Following local warfarin protocols to treat patients who are taking warfarin and whose upper gastrointestinal bleeding has stopped

Recombinant factor Vlla (eptacog alfa) when all other methods have failed.

If any medications are temporarily stopped, also seek advice on the appropriate time for these to be re-started. The 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline on endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy recommends restarting anticoagulation:[50]

As soon as possible after 7 days of anticoagulant interruption in patients with low thrombotic risk

Preferably within 3 days of anticoagulant interruption in patients with high thrombotic risk, with heparin bridging.

Patients taking aspirin, other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or dual antiplatelet therapy

If the patient is taking aspirin, other NSAIDs (including cyclo-oxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitors), or dual antiplatelet therapy:

In general, continue aspirin with gastroprotection in the acute phase, if your patient is taking this for secondary prevention.[50][56][59][64][79]

Consider seeking urgent advice from a specialist if there is major haemorrhage.

NICE doesn’t make a specific recommendation about major haemorrhage, but advises continuing aspirin only once haemostasis has been achieved.[56]

The BSG consensus care bundle for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline on endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy recommend continuing aspirin if this is taken as part of dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor (e.g., clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor), and the P2Y12 is temporarily stopped.[50][64]

The 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline recommends that, if aspirin is stopped, it should be restarted as soon as haemostasis is achieved or there is no further evidence of haemorrhage.[50]

The BSG care bundle cites two studies that demonstrate a three-fold increase in the risk of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events if aspirin, prescribed for secondary prevention, is discontinued.[50][64][79][80][81]

The 2021 update to the BSG and ESGE guideline recommends considering permanently discontinuing aspirin if the patient is taking it for primary prevention.[50]

If the patient is taking any other NSAIDs (including COX-2 inhibitors), NICE recommends stopping these during the acute phase.[50]

If the patient is taking dual antiplatelet therapy, seek advice from the appropriate specialist to weigh up the benefits and risks of continuing the P2Y12 inhibitor. Discuss the balance of benefits versus risk with your patient. In general, if the patient:[64]

Does not have coronary artery stents, the P2Y12 inhibitor should be stopped temporarily until haemostasis is achieved

Does have coronary artery stents, dual antiplatelet therapy should ideally be continued due to the high risk of stent thrombosis. However, the risks and benefits of doing so need to be carefully considered by a specialist.

If the ulcer is recurrent or resistant to treatment, the multidisciplinary specialists involved in the patient’s care should balance the risks and benefits of continued antiplatelet therapy.

After intervention to stop the bleeding, investigate the presence of H pylori and treat according to the guidelines for patients with no active bleeding.

Treatment is aimed at determining and eliminating the underlying cause, together with ulcer healing therapy. The major causative factors responsible for peptic ulceration are the use of NSAIDs and infection with H pylori. Determine the presence of H pylori because treatment is based on whether the patient is H pylori positive or negative.

H pylori negative

H pylori negative ulcers, the majority of which are associated with use of NSAIDs, are increasingly commonly seen, owing to a decline in prevalence of H pylori.[82]

For patients on NSAIDs with a diagnosed peptic ulcer, stop the NSAID where possible.[46]

If this is not possible, and in people at high risk (previous ulceration), consider a COX-2 inhibitor instead of a standard NSAID and prescribe a PPI.[46]

Start ulcer healing therapy.

Offer full-dose PPI therapy for 4 to 8 weeks to patients who are H pylori negative.[46]

H2 antagonists may be used if the patient is unresponsive to a PPI.[46]

Antacids are relatively ineffective and slow to produce healing and are not recommended.

Adverse effects of PPI therapy include diarrhoea, nausea, and modest increases in gastrin levels. They may also mask the symptoms of gastric cancer.

If diarrhoea develops, consider Crohn’s disease, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, microscopic colitis (lymphocytic or collagenous colitis) and more rarely, Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Review the need for treatment.[48]

H pylori positive

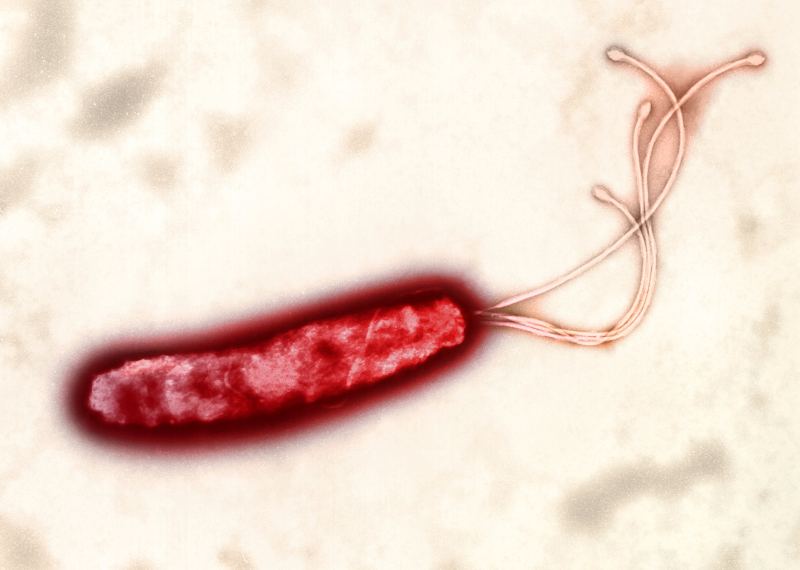

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Helicobacter pylori bacterium, transmission electron micrograph (TEM)Heather Davies/Science Photo Library [Citation ends].

If the H pylori positive patient is not a long-term user of NSAIDs:

Offer a 7-day course of H pylori eradication therapy.[46]

This is in line with recommendations from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).[46]

Consider offering ulcer healing therapy with a full-dose PPI or H2 antagonist for 8 weeks

This is standard practice in the UK based on clinical experience but bear in mind that ulcer healing therapy is not specifically recommended for this group by NICE.

If the H pylori positive patient is a long-term user of NSAIDs (or low-dose aspirin):[46]

Discontinue any NSAID the patient is taking, if possible.[46] If this is not possible, and in people at high risk (previous ulceration), consider a COX-2 inhibitor instead of a standard NSAID and prescribe a PPI.[46]

Weigh up the benefits versus risks of reducing or stopping any other potential ulcer-inducing drugs, including aspirin.[83] Seek senior/specialist advice if low-dose aspirin is being taken for secondary prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events as the benefits of continuing may need to take priority.[79]

NICE recommends to:

Be aware that ulcer healing therapy and eradication therapy are sequential treatments. In practice, a specialist may advise eradication therapy before ulcer healing therapy or vice-versa based on their clinical experience and preference. Always follow your local protocols and use your clinical judgment to determine the optimal approach for your individual patient.

H pylori eradication therapy

Eradication therapy leads to ulcer healing and a dramatic decrease in ulcer recurrence.[84]

[  ]

[

]

[  ]

Most regimens are 70% to 90% efficacious in practice, limited mainly by antibiotic resistance or patient adherence to the regimen. Delayed clearance of H pylori is associated with a higher rate of subsequent upper gastrointestinal bleeding.[85]

]

Most regimens are 70% to 90% efficacious in practice, limited mainly by antibiotic resistance or patient adherence to the regimen. Delayed clearance of H pylori is associated with a higher rate of subsequent upper gastrointestinal bleeding.[85]

Check the patient’s antibiotic history, ascertain antibiotic allergy status, and stress the importance of adherence.

Eradication regimens vary between guidelines and locations; traditional empirical ‘triple therapies’ rarely achieve satisfactory eradication rates, and success rates vary according to local and regional resistance patterns.[86] Empirical therapies should be restricted to those shown to be highly effective locally.[53][86][87]

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Public Health England (PHE) make specific recommendations on treatment regimens, but note that these will often need to be substituted with local protocols that take account of resistance patterns because traditional empirical 'triple therapies' often fail to achieve successful eradication:[46][48]

First-line triple therapy for 7 days with a course of a PPI plus two antibiotics; NICE and PHE recommend amoxicillin plus either clarithromycin or metronidazole. Alternative regimens are outlined for people who are penicillin-allergic or who have had previous clarithromycin exposure.

Other guidelines recommend alternative approaches: for example, the European guidelines recommend bismuth quadruple therapy (a PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole) as initial treatment.[53]

For patients who continue to take NSAIDs after a peptic ulcer has healed, discuss the potential harm associated with NSAIDs.[46]

Review the need for NSAID use regularly (at least every 6 months)

Offer a trial of NSAID use on a limited 'as needed' basis[46]

Consider:[46]

Reducing the NSAID dose

Substituting the NSAID with paracetamol

Using an alternative analgesic

Using low-dose ibuprofen.

In people at high risk (previous ulceration) and for whom NSAID continuation is necessary, consider a COX-2 inhibitor instead of a standard NSAID. In either case, prescribe with a PPI.[46]

In people with an unhealed ulcer, exclude non-adherence, malignancy, failure to detect H pylori, inadvertent or surreptitious NSAID use, other ulcer-inducing medication, and rare causes such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome or Crohn's disease.[46]

If symptoms recur after initial treatment, offer a PPI at the lowest dose possible to control symptoms.[46]

Encourage patients to manage their own symptoms by using PPI treatment on an 'as-needed' basis.[46]

Offer H2 antagonist therapy if there is an inadequate response to a PPI.[46]

Long-term maintenance acid-suppression therapy may be used in selected high-risk patients (e.g., frequent recurrences, large or refractory ulcers) with or without H pylori infection. The preferred regimen and duration of therapy is uncertain, although most clinicians use a PPI.

Safety of long-term PPI therapy

PPIs are an effective treatment for peptic ulcer disease.[45] Concerns exist, however, over their long-term use.

Retrospective analyses suggest an association between PPI use and osteoporosis, pneumonia, dementia, stroke, and all-cause mortality.[88][89][90][91][92][93][94] However, these studies are unable to establish a causal relationship.[95]

A prospective analysis of more than 200,000 participants in three big studies, over a combined 2.1 million person-years of follow-up, found that regular use of PPIs was associated with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.31). The risk of diabetes increased with duration of PPI use.[96]

In possibly the largest prospective randomised PPI trial for any indication (n=17,958 patients with cardiovascular disease), no significant difference in adverse effects was reported between pantoprazole and placebo at 3 years (53,000 patient years of follow-up), aside from a possible increase in enteric infection.[97]

One smaller prospective, multicentre double-blind study, including 115 healthy post-menopausal women, found that 26 weeks of treatment with a PPI had no clinically meaningful effects on bone homeostasis.[98]

A systematic review and meta-analysis that included more than 600,000 patients found no relationship between the use of PPIs and increased risk of dementia.[99] This was also the conclusion in another meta-analysis of just over 200,000 patients, where no clear evidence was found to suggest an association between PPI use and risk of dementia.[100]

A cohort study of more than 700,000 patients in the UK showed an association between PPI use and all-cause mortality.[94] However, significant confounding effects mean that conclusions about causality cannot be made.[94]

PPIs are associated with changes in the microbiome. The clinical significance of these changes is uncertain.[101]

PPIs should only be prescribed for appropriate indications and should be limited to the warranted therapeutic duration of therapy. Based on current data, the overall benefits of PPI treatment outweigh the potential risks in most patients.

Drug safety alert: Adverse events associated with long-term use of PPIs

Concerns exist over the long-term use of PPIs.

Severe hypomagnesaemia has been reported infrequently in patients treated with PPIs, rarely after 3 months, but usually after 1 year of treatment. Serious features of hypomagnesaemia include fatigue, tetany, delirium, convulsions, dizziness, and ventricular arrhythmia. Hypomagnesaemia usually improves after magnesium replacement and discontinuation of the PPI.[102]

PPIs have been associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and a modest increase in the risk of hip, wrist, or spine fracture, especially if used by older people in high doses and for >1 year.[103]

PPIs have been linked rarely, but probably causally, to subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE).[104]

In being vigilant for these rare adverse events:

Consider measuring magnesium levels before starting PPI treatment and periodically during prolonged treatment, especially in those who take concomitant digoxin or drugs that may cause hypomagnesaemia (e.g., diuretics).[102]

Treat patients at risk of osteoporosis according to current clinical guidelines to ensure they have an adequate intake of vitamin D and calcium.[103]

Advise patients who develop arthralgia and skin lesions in sun-exposed areas to avoid sunlight, and consider giving topical or systemic corticosteroids if there are no signs of remission after a few weeks or months.[104]

Consider stopping the PPI unless it is imperative for a serious acid-related condition.

Take into account any use of PPIs obtained over-the-counter.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer